Lexical Peculiarities of Scottish English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British, Scottish, English?

Scottish, English, British? coding for attitude in the UK Carmen Llamas University of York, UK Satellite Workshop for Sociolinguistic Archival Preparation attitudes ‘attitudes to language varieties underpin all manners of sociolinguistic and social psychological phenomena’ (Garrett et al., 2003: 12) ‘a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor’ (Eagley & Chaiken, 1993: 1) . components: cognitive beliefs affective feelings behavioural readiness for action speaker-internal mental constructs - methodologically challenging • direct and indirect observation: •explicit attitudes – e.g. interviews, self-completion written questionnaires • implicit attitudes – e.g. matched-guise technique, IATs borders • ideal test site for investigation of how variable linguistic behaviour is connected to attitudes – border area • fluid and complex identity construction at such sites mean border regions have particular sociolinguistic relevance • previous sociological research in and around Berwick-upon- Tweed (English town) (Kiely et al. 2000) – around half informants felt Scottish some of the time the border • Scottish~English border still seen as particularly divisive: What appears to be the most numerous bundle of dialect isoglosses in the English-speaking world runs along this border, effectively turning Scotland into a “dialect island”. (Aitken 1992:895) • predicted to become more divisive still: the Border is becoming more and more distinct linguistically as the 20th century progresses. (Kay 1986:22) ... the dividing effect of the geographical border is bound to increase. (Glauser 2000: 70) • AISEB tests these predictions by examining the linguistic and socio-psychological effects of the border the team Dominic Watt (York) Gerry Docherty (Newcastle) Damien Hall (Kent) Jennifer Nycz (Reed College) UK Economic & Social Research Council (RES-062-23-0525) AISEB three-pronged approach production • quantitative analysis of phonological variation and change attitude • cognitive vs. -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

The Norse Element in the Orkney Dialect Donna Heddle

The Norse element in the Orkney dialect Donna Heddle 1. Introduction The Orkney and Shetland Islands, along with Caithness on the Scottish mainland, are identified primarily in terms of their Norse cultural heritage. Linguistically, in particular, such a focus is an imperative for maintaining cultural identity in the Northern Isles. This paper will focus on placing the rise and fall of Orkney Norn in its geographical, social, and historical context and will attempt to examine the remnants of the Norn substrate in the modern dialect. Cultural affiliation and conflict is what ultimately drives most issues of identity politics in the modern world. Nowhere are these issues more overtly stated than in language politics. We cannot study language in isolation; we must look at context and acculturation. An interdisciplinary study of language in context is fundamental to the understanding of cultural identity. This politicising of language involves issues of cultural inheritance: acculturation is therefore central to our understanding of identity, its internal diversity, and the porousness or otherwise of a language or language variant‘s cultural borders with its linguistic neighbours. Although elements within Lowland Scotland postulated a Germanic origin myth for itself in the nineteenth century, Highlands and Islands Scottish cultural identity has traditionally allied itself to the Celtic origin myth. This is diametrically opposed to the cultural heritage of Scotland‘s most northerly island communities. 2. History For almost a thousand years the language of the Orkney Islands was a variant of Norse known as Norroena or Norn. The distinctive and culturally unique qualities of the Orkney dialect spoken in the islands today derive from this West Norse based sister language of Faroese, which Hansen, Jacobsen and Weyhe note also developed from Norse brought in by settlers in the ninth century and from early Icelandic (2003: 157). -

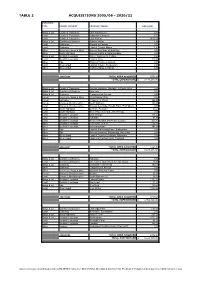

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

May and June 2020 Newsletter

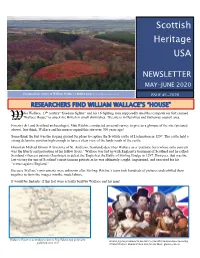

Scottish Heritage USA NEWSLETTER MAY-JUNE 2020 Presumed site of 0ne of William Wallace’s hidden forts (©FLS by Skyscape survey 2020) ISSUE #1-2020 RESEARCHERS FIND WILLIAM WALLACE’S “HOUSE” ilia Wallace, 13th century “freedom fighter” and his 16 fighting men supposedly used this campsite (or fort) named W “Wallace House” to attack the British in small skirmishes. The site is in Dumfries and Galloway council area. Forestry & Land Scotland archaeologist, Matt Ritchie, conducted an aerial survey to give us a glimpse of the site (pictured above). Just think, Wallace and his men occupied this site over 700 years ago! Some think the fort was the staging ground for plans to capture the Scottish castle of Lochmaben in 1297. The castle held a strong defensive position high enough to have a clear view of the lands south of the castle. Historian Michael Brown (University of St. Andrews, Scotland) describes Wallace as a “patriotic hero whose only concern was the liberty and protection of his fellow Scots.” Wallace was fed up with England’s treatment of Scotland and he rallied Scotland’s fiercest patriots (Jacobites) to defeat the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. However, that was the last victory for one of Scotland’s most famous patriots as he was ultimately caught, imprisoned, and executed for his “crimes against England.” Because Wallace’s movements were unknown after Stirling, Ritchie’s team took hundreds of pictures and cobbled them together to form the images into the model above. It would be fantastic if this fort were actually built by Wallace and his men! Wallace’s House on an Ordinance Survey First Edition map of the area, Several figures prominent in the history of Scottish Independence including published circa 1857 William Wallace, Bonnie Prince Charlie and Mary, Queen of Scots. -

Dialectal Diversity in Contemporary Gaelic: Perceptions, Discourses and Responses Wilson Mcleod

Dialectal diversity in contemporary Gaelic: perceptions, discourses and responses Wilson McLeod 1 Introduction This essay will address some aspects of language change in contemporary Gaelic and their relationship to the simultaneous workings of language shift and language revitalisation. I focus in particular on the issue of how dialects and dialectal diversity in Gaelic are perceived, depicted and discussed in contemporary discourse. Compared to many minoritised languages, notably Irish, dialectal diversity has generally not been a matter of significant controversy in relation to Gaelic in Scotland. In part this is because Gaelic has, or at least is depicted as having, relatively little dialectal variation, in part because the language did undergo a degree of grammatical and orthographic standardisation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with the Gaelic of the Bible serving to provide a supra-dialectal high register (e.g. Meek 1990). In recent decades, as Gaelic has achieved greater institutionalisation in Scotland, notably in the education system, issues of dialectal diversity have not been prioritised or problematised to any significant extent by policy-makers. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been some evidence of increasing concern about the issue of diversity within Gaelic, particularly as language shift has diminished the range of spoken dialects and institutionalisation in broadcasting and education has brought about a degree of levelling and convergence in the language. In this process, some commentators perceive Gaelic as losing its distinctiveness, its richness and especially its flavour or blas. These responses reflect varying ideological perspectives, sometimes implicating issues of perceived authenticity and ownership, issues which become heightened as Gaelic is acquired by increasing numbers of non-traditional speakers with no real link to any dialect area. -

The Mother Tongue J Derrick Mcclure

The Mother Tongue J Derrick McClure We are grateful to J Derrick McClure for writing this article for inclusion on the Scots Language Centre website. ********** The old Scots tongue, the language that can still be heard in the mouth of many a lad and lass from the Shetland Isles to the Mull of Galloway, has as wonderful a history as any of the languages of the world. To understand the life of any language, we must know two things. We must know the structure of the language itself: its sounds and spelling, its grammar, its words. And we must also know what the language means, and has meant, to the people who speak it. There is no language that has not changed with the passing of the years: the English of Shakespeare is not the English spoken today. A language can change so much that it becomes an entirely different thing: French, Italian, Spanish and several other European tongues were all one and the same language, Latin, many centuries ago. And a language can simply die, leaving no trace: the Indians of America and Canada have now for the most part forgotten their mother tongues and speak only English, and many people fear that if we are not careful our own Gaelic and Scots will go the same way. Gaelic is related to Irish; Scots is related to English. What that means is that there was once a single language - Old Irish for one of the pairs, Old English (sometimes called "Anglo-Saxon") for the other - which divided into two, developing and changing in different ways in the kingdoms of Scotland and Ireland, or Scotland and England. -

Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’S New Year’S Eve Celebrations

Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge Suggested citation: Frew, E. & Mair. J. (2014). Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations. In Frost, W. & Laing, J. (Eds) Rituals and traditional events in the modern world. Routledge Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations Elspeth A. Frew La Trobe University Judith Mair Department of Management Monash University ABSTRACT Hogmanay, which is the name given to New Year’s Eve in Scotland, is a long-standing festival with roots going far back into pagan times. However, such festivals are losing their traditions and are becoming almost generic public celebrations devoid of the original rites and rituals that originally made them unique. Using the framework of Falassi’s (1987) festival rites and rituals, this chapter utilises a duoethnographic approach to examine Hogmanay traditions in contemporary Scotland and the extent to which these have been transferred to another country. The chapter reflects on the traditions which have survived and those that have been consigned to history. Hogmanay and Paganism: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations INTRODUCTION New Year’s Eve (or Hogmanay as it is known in Scotland) is celebrated in many countries around the world, and often takes the form of a public celebration with fireworks, music and a carnival atmosphere. However, Hogmanay itself is a long-standing festival in Scotland with roots going far back into pagan times. Some of the rites and rituals associated with Hogmanay are centuries old, and the tradition of celebrating New Year Eve (as Hogmanay) on a grander scale than Christmas has been a part of Scottish life for many hundreds of years. -

January 2021 Newsletter

Scottish Heritage USA NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2021 Vikings leading the Hogmanay Torchlight Parade, Edinburgh ISSUE #1-2021 HAPPY NEW YEAR & HAPPY HOGMANAY! H OGMANAY may be Scotland’s New Year celebration, but it lasts three to five days with unusual, weird and wild H traditions. It starts on Christmas with the Edinburgh Torchlight Parade and is all downhill from there! Look to Scotland to find the best, most spectacular fire festivals in the UK. Combine the primitive impulse to light up the long nights (the ancient idea that fire purifies and chases away evil spirits) and the natural Scottish impulse to party to the wee small hours and you end up with some of the most dazzling and daring midwinter celebrations in Europe. At one time, most Scottish towns celebrated the New Year with huge bonfires and torchlight processions. Many have disappeared, but those that are left are real Site where the horde was found humdingers. Here are the five of the best winter fire festivals in Scotland: STONEHAVEN FIRE FESTIVAL: Strong Scots dare-devils parade through the town on New Year's Eve swinging 16-pound balls of fire around themselves and over their heads. Each "swinger" has his or her own secret recipe for creating the fireball and keeping it lit. Thousands come to watch this famous event on the North Sea, south of Aberdeen. It all gets underway before midnight with bands of pipers and wild drumming. Then a lone piper, playing Scotland the Brave, leads the pipers into town. At the stroke of midnight, they raise their flaming balls over their heads and begin to swing and twirl them, showering the street, themselves and usually the 12,000 strong crowd, with sparks. -

Scotland's New Year Festival

SCOTLAND’S NEW YEAR FESTIVAL FOREWORD A very warm welcome to you in our third year of producing Edinburgh’s Hogmanay, as we invite you to BE TOGETHER this Hogmanay. Now more than ever is the time to celebrate ‘togetherness’ and what better way than surrounded by people from all over the world at New Year? From performers to audiences, this festival is about coming together, being together, sharing experiences together and sharing the start of a new year arm in arm and side by side. BE ready to party from the 30th December as we return with a programme of events at the magnificent McEwan Hall. From the return of hit clubbing experience Symphonic Ibiza on 30th December featuring Ibiza DJs and a live orchestra, to the first party in 2020 celebrating the new year along with the Southern Hemisphere at G’Day 2020 with Kylie Auldist on 31 December. Jazz legends Ronnie Scott’s Big Band will play a gala concert on 31st December to give an alternative lead up to the bells and renowned DJ Judge Jules will spin into the wee small hours at our first ever Official After-Party. BE a trailblazer at the Torchlight Procession in partnership with VisitScotland. The historic event culminates in Holyrood Park as torchbearers create a symbol to share with the world: this year two figures holding hands - both residents and visitors to Scotland opening their door to the world and saying BE together. BE in the thick of it at the world famous Street Party hosted by Johnnie Walker, with a brilliantly eclectic programme of music, street theatre and spectacle. -

"I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speth, Alana, ""I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624392. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-szar-c234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth Nicholson, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alana Speth Approved by the Committee L Committee Chair Pullen Professor James Whittenburg, History The College of William and Mary Professor LuAnn Homza, History The College of William and Mary • 7 i ^ i Assistant Professor Kathrin Levitan, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE The radical and complex changes that unfolded in the Scottish Highlands beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century have often been depicted as an example of mainstream British assimilation.