Where Truth Is No Defence I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagner Intoxication

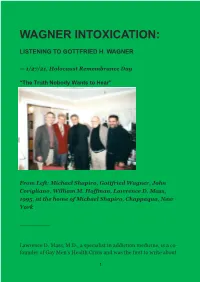

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Books, Maps and Photographs

BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Tuesday 25 November 2014 Oxford BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS | Oxford | Tuesday 25 November 2014 | Tuesday | Oxford 21832 BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Tuesday 25 November 2014 at 11.00 Oxford BONHAMS Live online bidding is CUstomER SErvICES Important INFormatION Banbury Road available for this sale Monday to Friday 8.30 to 18.00 The United States Shipton on Cherwell Please email bids@bonhams. +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Government has banned the Kidlington com with ‘live bidding’ in the import of ivory into the USA. Oxford OX5 1JH subject line 48 hours before the Please see page 2 for bidder Lots containing ivory are bonhams.com auction to register for this information including after-sale indicated by the symbol Ф service collection and shipment printed beside the lot number VIEWING in this catalogue. Saturday 22 November 09.00 to Please note we only accept SHIPPING AND COLLECTIONS 12.00 telephone bids for lots with a Oxford Monday 24 November 09.00 to low estimate of £500 or Georgina Roberts 16.30 higher. Tuesday 25 November limited +44 (0) 1865 853 647 [email protected] viewing 09.00 to 10.30 EnQUIRIES Oxford BIDS London John Walwyn-Jones +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Jennifer Ebrey Georgina Roberts +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7393 3841 Sian Wainwright To bid via the internet please [email protected] +44 (0) 1865 853 646 visit bonhams.com +44 (0) 1865 853 647 Please see back of catalogue +44 (0) 1865 853 648 Please note that bids should be for important notice to +44 (0) 1865 372 722 fax submitted no later than 24 hours bidders prior to the sale. -

Introduction to the Second Edition

Introduction to the Second Edition By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute Remember the Women Institute has created this Women, Theatre, and the Holocaust Resource Handbook as a service to educators and others for whom this information is relevant and necessary. The information here is also intended to be incorporated into two larger projects: the Holocaust Theater Catalog of the National Jewish Theater Foundation, as well as a virtual Holocaust Theatre Online Collection (currently only in Hebrew) for All About Jewish Theatre. We are pleased to be part of both of these larger projects, the former based in the United States and the latter, in Israel. We launched the first edition of this resource handbook in April 2015, at a Yom HaShoah commemoration co-sponsored by Remember the Women Institute, American Jewish Historical Society, and All About Jewish Theatre, and held at the Center for Jewish History, New York. The event coincided with the Remembrance Readings Day of National Jewish Theater Foundation, which encourages using theatre to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive. This new updated 2016 edition of the resource handbook is also being released in conjunction with Remembrance Readings Day on May 2, with a program of readings at the Center for Jewish History in New York, co-sponsored by the American Jewish Historical Society. Like the 2015 event, the program is a reflection of the goals of this resource handbook: providing information on and encouraging the production of plays and dramatic presentations about the Holocaust that are written by women and/or about the experience of women during the Holocaust. -

“The Battle for the Enlightenment”: Rushdie, Islam, and the West

i “The Battle for the Enlightenment”: Rushdie, Islam, and the West Adam Glyn Kim Perchard PhD University of York English and Related Literature August 2014 ii iii Abstract In the years following the proclamation of the fatwa against him, Salman Rushdie has come to view the conflict of the Rushdie Affair not only in terms of a struggle between “Islam” and “the West”, but in terms of a “battle for the Enlightenment”. Rushdie’s construction of himself as an Enlightened war-leader in the battle for a divided world has proved difficult for many critics to reconcile with the Rushdie who advocates “mongrelization” as a form of life-giving cultural hybridity. This study suggests that these two Rushdies have been in dialogue since long before the fatwa. It also suggests that eighteenth-century modes of writing and thinking about, and with, the Islamic East are far more integral to the literary worlds of Rushdie’s novels than has previously been realised. This thesis maps patterns of rupture and of convergence between representations of the figures of the Islamic despot and the Muslim woman in Shame, The Satanic Verses, and Haroun and the Sea of Stories, and the changing ways in which these figures were instrumentalised in eighteenth-century European literatures. Arguing that many of the harmful binaries that mark the way Rushdie and others think about Islam and the West hardened in the late eighteenth century, this study folds into the fable of the fatwa an account of European literary engagements with the Islamic world in the earlier part of the eighteenth century. -

Breaking Intergenerational Cycles of Repetition. a Global Dialogue on Historical Trauma and Memory

Breaking Intergenerational Cycles of Repetition Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela (ed.) Breaking Intergenerational Cycles of Repetition A Global Dialogue on Historical Trauma and Memory Barbara Budrich Publishers Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2016 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8474-0240-4. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org © 2016 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0. (CC- BY-SA 4.0) It permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you share under the same license, give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ © 2016 Dieses Werk ist beim Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH erschienen und steht unter der Creative Commons Lizenz Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Diese Lizenz erlaubt die Verbreitung, Speicherung, Vervielfältigung und Bearbeitung bei Verwendung der gleichen CC-BY-SA 4.0-Lizenz und unter Angabe der UrheberInnen, Rechte, Änderungen und verwendeten Lizenz. This book is available as a free download from www.barbara-budrich.net (https://doi.org/10.3224/84740613). -

Khatyn Thesis***

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Michael Guthrie Dorman 2017 The Thesis Committee for Michael Guthrie Dorman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Khatyn and the Myth of Genocide in Lukashenko’s Belarus APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Charters Wynn Oksana Lutsyshyna Khatyn And The Myth of Genocide In Lukashenko’s Belarus by Michael Guthrie Dorman Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2017 Abstract Khatyn And The Myth of Genocide In Lukashenko’s Belarus Michael Guthrie Dorman, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Charters Wynn During the German occupation of Soviet Belarus, punitive actions against the local population were a common occurrence. Often these actions included the destruction of villages along with part or all of their inhabitants. In March of 1943 the village of Khatyn was burned to the ground along with all of its inhabitants by Nazi troops, many of whom were from Western Ukraine. Though more than 600 Belarusian villages met a similar fate, the site of the Khatyn massacre was chosen for the construction of an expansive memorial complex in 1969. Over the course of its existence, the Khatyn memorial has become one of the most important symbols of the tremendous loss of life and suffering the Second World War inflicted on Belarus. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE Growing Up in Nazi Germany: Teaching Friedrich by Hans Peter Richter GROWING UP IN NAZI GERMANY: Teaching Friedrich by Hans Peter Richter Table of Contents INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 LESSON PLANS FOR INDIVIDUAL CHAPTERS Setting the Scene (1925) PAGE 3 In the Swimming Pool (1938) PAGE 42 Potato Pancakes (1929) PAGE 4 The Festival (1938) PAGE 44 Snow (1929) PAGE 6 The Encounter (1938) PAGE 46 Grandfather (1930) PAGE 8 The Pogrom (1938) PAGE 48 Friday Evening (1930) PAGE 10 The Death (1938) PAGE 52 School Begins (1931) PAGE 12 Lamps (1939) PAGE 53 The Way to School (1933) PAGE 14 The Movie (1940) PAGE 54 The Jungvolk (1933) PAGE 16 Benches (1940) PAGE 56 The Ball (1933) PAGE 22 The Rabbi (1941) PAGE 58 Conversation on the Stairs (1933) PAGE 24 Stars (1941) PAGE 59 Herr Schneider (1933) PAGE 26 A Visit (1941) PAGE 61 The Hearing (1933) PAGE 28 Vultures (1941) PAGE 62 In the Department Store (1933) PAGE 30 The Picture (1942) PAGE 64 The Teacher (1934) PAGE 32 In the Shelter (1942) PAGE 65 The Cleaning Lady (1935) PAGE 35 The End (1942) PAGE 67 Reasons (1936) PAGE 38 RESOURCE MATERIALS PAGE 68 This curriculum is made possible by a generous grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany: The Rabbi Israel Miller Fund for Shoah Research, Documentation and Education. Additional funding has been provided by the Estate of Else Adler. The Museum would also like to thank the Board of Jewish Education of Greater New York for their input in the project, and Ilana Abramovitch, Ph.D. -

Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland During World War II1

July 2008 Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II1 Mark Paul Collaboration with the Germans in occupied Poland is a topic that has not been adequately explored by historians.2 Holocaust literature has dwelled almost exclusively on the conduct of Poles toward Jews and has often arrived at sweeping and unjustified conclusions. At the same time, with a few notable exceptions such as Isaiah Trunk3 and Raul Hilberg,4 whose findings confirmed what Hannah Arendt had written about 1 This is a much expanded work in progress which builds on a brief overview that appeared in the collective work The Story of Two Shtetls, Brańsk and Ejszyszki: An Overview of Polish-Jewish Relations in Northeastern Poland during World War II (Toronto and Chicago: The Polish Educational Foundation in North America, 1998), Part Two, 231–40. The examples cited are far from exhaustive and represent only a selection of documentary sources in the author’s possession. 2 Tadeusz Piotrowski has done some pioneering work in this area in his Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces, and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998). Chapters 3 and 4 of this important study deal with Jewish and Polish collaboration respectively. Piotrowski’s methodology, which looks at the behaviour of the various nationalities inhabiting interwar Poland, rather than focusing on just one of them of the isolation, provides context that is sorely lacking in other works. For an earlier treatment see Richard C. Lukas, The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation, 1939–1944 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986), chapter 4. -

Aspectos Da Presença De Autores Franceses Do Século Xviii Nas Crônicas Machadianas E Suas Implicações Intertextuais

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS MODERNAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS, LITERÁRIOS E TRADUTOLÓGICOS EM FRANCÊS DIRCEU MAGRI ASPECTOS DA PRESENÇA DE AUTORES FRANCESES DO SÉCULO XVIII NAS CRÔNICAS MACHADIANAS E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES INTERTEXTUAIS (VERSÃO CORRIGIDA) SÃO PAULO 2014 Nome: MAGRI, Dirceu. Título: Aspectos da presença de autores franceses nas crônicas machadianas e suas implicações intertextuais Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Estudos Linguísticos, Literários e Tradutológicos em Francês do Departamento de Letras Modernas, da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Letras - Língua e Literatura Francesa. Aprovado em: _____/_____/_______. Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr.: ____________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________Assinatura: ___________________ Prof. Dr.: ____________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________Assinatura: ___________________ Prof. Dr.: ____________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________Assinatura: ___________________ Prof. Dr.: ____________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________Assinatura: ___________________ Prof. Dr.: ____________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________Assinatura: ___________________ 3 Li tudo, misturei, digeri, e aqui estou. Machado de Assis, -

Rethinking the Mythical Standard Accounts of the Enlightenment Höög, Victoria

Rethinking the Mythical Standard Accounts of the Enlightenment Höög, Victoria Published in: Insikt & Handling 2018 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Höög, V. (2018). Rethinking the Mythical Standard Accounts of the Enlightenment. Insikt & Handling, 26, 7-17. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 INSIKT OCH HANDLING editor victoria höög INSIKT OCH HANDLING Published by Hans Larsson Society lund university sweden Volume 26 Theme What is Left of the Enlightenment? -

Independant Reading List

SPRINGBOARD LEVEL I - III SUPPLEMENTAL READING LIST (LIT CIRCLES & INDEPENDENT TITLES) * indicates Springboard Text or Author Level I (6th): Changes Unit 1: Changes in Me Autobiographical writing (personal narrative, memoir, autobiographical account) Fiction or nonfiction narrative * Bad Boy by Walter Dean Myers In his memoir, Walter Dean Myers describes the details of his Harlem childhood in the 1940s and 1950s. Although Walter spent much of his time either getting into trouble or on the basketball court, secretly he was a voracious reader and aspiring writer. Breaking Through by Francisco Jimenez In this sequel to the circuit: stories from the life of a migrant child, Francisco Jimenez and his family struggle to keep their family together after being caught by la migra. The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child by Francisco Jimenez This is an honest and powerful account of the author and his family's journey from Mexico to California when he was a child. Girl Who Owned a City by O.T. Nelson (Graphic Novel) When a plague sweeps over the earth killing everyone except children under twelve, ten- year-old Lisa organizes a group to rebuild a new way of life. Harris and Me by Gary Paulsen A young boy is sent to spend the summer on his aunt and uncle's farm. Though he has lived many places over the years, he has never experienced anything like farm life, and he has ever met anyone like Harris, his daredevil of a cousin. Can the two survive the summer? Living Up the Street by Gary Soto Gary Soto's coming of age in the barrio of Fresno's industrial side: parochial school, attending church, and trying to fall out of love so he can join in a Little League baseball team. -

Domestic and International Trials, 1700-2000

Domestic and international trials, 1700–2000 Domestic and international trials, 1700–2000 The trial in history, volume II edited by R. A. Melikan Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2003 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC- ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6486 4 hardback First published 2003 1009080706050403 10987654321 Typeset in Photina by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton iv Contents List of figures and tables page vi List of contributors vii Acknowledgements ix List of legal abbreviations x Introduction R. A. Melikan 1 1 Evidence law and the evidentiary objection: a view from the British Trials collection T. P. Gallanis 12 2 Sense and sensibility: fateful splitting in the Victorian insanity trial Joel Peter Eigen 21 3 Trials of character: the use of character evidence in Victorian sodomy trials H.