Sahel Development Program Annual Report to the Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER

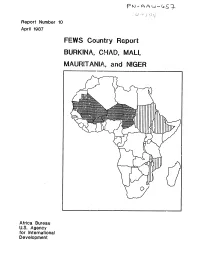

Report Number 10 April 1987 FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development Summary Map __ Chad lMurltanl fL People displaced by fighting High percentage of population have bothL.J in B.E.T. un~tfood needsa nd no source of income - High crop oss cobied with WESTERN Definite increases in retes of malnutrition at CRS centers :rom scarce mrket and low SAHARA .ct 1985 through Nov 196 ,cash income Areas with high percentage MA RTAI of vulnerable LIBYA MAU~lAN~A/populations / ,,NIGER SENEGAL %.t'"S-"X UIDA Areas at-risk I/TGI IEI BurkinaCAMEROON Areas where grasshoppers r Less than 50z of food needs met combined / CENTRAL AFRICAN would have worst impact Fi with absence of government stocks REPLTL IC if expected irdestat ions occur W Less than r59 of food needs met combined ith absence of government stocks FEYIS/PWA. April 1987 Famine Early Warning System Country Report BURKINA CHAD MALI MAURITANIA NIGER Populations Under Duress Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. April 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 2 Burkina 6 Chad 9 Mali 12 Mauritania 18 Niger 2f FiAures 3 Map 2 Burkina, Grain Supply and OFNACER Stocks 4 Table I Burkina, Production and OFNACER Stocks 6 Figure I Chad, Prices of Staple Grains in N'Djamcna 7 Map 3 Chad, Populations At-Risk 10 Table 2 Mali, Free Food Distribution Plan for 1987 II Map 4 Mali, Population to Receive Food Aid 12 Figure 2 Mauritania, Decreasing -

Appraisal Report

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND MAU/PAAL/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT AND RANGE MANAGEMENT ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA NB: This document contains errata or corrigenda (see Annexes) COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDN NORTH REGION SEPTEMBER 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONENTS Page PROJECT BRIEF, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, PROJECT MATRIX, CURRENCY i-ix EQUIVALENTS, LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF TABLES, LIST OF ANNEXES, COMPARATIVE SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS 1. ORIGIN AND PROJECT BACKGROUND 1 2. THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 1 2.1 Main Features 1 2.2 Natural Resources and Products 2 2.3 Land Tenure System 2 2.4 Rural Poverty 2 3. THE LIVESTOCK SUB-SECTOR 3 3.1 Importance of the Sub-Sector 3 3.2 Livestock Systems 3 3.3 Institutions of Sub-sector 4 3.4 Sub-sector Constraints 6 3.5 Government Policy and Strategy 7 3.6 Donor Interventions 7 4. THE PROJECT 8 4.1 Project Design and Rationale 8 4.2 Project Impact Area and Beneficiaries 8 4.3 Strategic Context 9 4.4 Project Objective 9 4.5 Project Description 9 4.6 Production, Marketing and Prices 13 4.7 Environmental Impact 13 4.8 Project Costs 14 4.9 Sources of Finance 15 5. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 16 5.1 Executing Agency 16 5.2 Institutional Provisions 18 5.3 Implementation and Supervision Schedule 19 5.4 Provisions Relating to the Procurement of Goods and Services 19 5.5 Provisions Relating to Disbursement 21 5.6 Monitoring and Evaluation 21 5.7 Financial Statements and Audit 22 5.8 Aid Coordination 22 TABLE OF CONTENTS (cont’d) Page 6. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 12606-MAU Mauritania Country EnvironmentalStrategy Paper Public Disclosure Authorized June30, 1994 Africa Region Sahelian Departnient Public Disclosure Authorized U Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized I ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AMEXTIPE Mauritanian Agency for Public Works AgenceMauritanienne d'Execution des and Employment Travauxdlnteret Publicet pour l'Emploi CESP CountryEnvironumental Strategy Paper Documentde Strategie Environnementale CNEA NationalCenter for AlternativeEnergy Cellule Nationale des Energies Alternatives DEAR Departmentof Environmentand Rural Direction de lEnvironnement et de Planning l'Am6nagementRural EC EuropeanCommunity CommunauteEuropeene GEF GlobalEnvironment Facility Fondspour l'EnvironnementMondial IUCN WorldConservation Union Union Mondialepour la Nature LPG LiquidPropane Gas MDRE Ministry of Rural Development and Minist&re du Developpement et de Envirorunent l'Environnement MHE Ministryof Water and Energy Ministere de lHydraulique et de lEnergie MS Ministryof Health Ministerede la Sante NEAP NationalEnvironmental Action Plan Plan dAction National pour l'Environnement NRM Natural ResourceManagement Gestiondes RessourcesNaturelles OMVS Organization for the Development of Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur the SenegalRiver Valley du FleuveSenegal PAs PastoralAssociations AssociationsPastorales UNCED United Nations Conference on Environmentand Development UNDP United Nations Development Programmedes Nations Unies pour la Programme Developpement UNSO -

Mauritania's Campaign of Terror: State-Sponsored Repression of Black Africans

MAURITANIA'S CAMPAIGN OF TERROR State-Sponsored Repression of Black Africans Human Rights Watch/Africa (formerly Africa Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $ Washington $ Los Angeles $ London Copyright 8 April 1994 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94-75822 ISBN: 1-56432-133-9 Human Rights Watch/Africa (formerly Africa Watch) Human Rights Watch/Africa is a non-governmental organization established in 1988 to monitor promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Africa. Abdullahi An- Na'im is the director; Janet Fleischman is the Washington representative; Karen Sorensen, Alex Vines, and Berhane Woldegabriel are research associates; Kimberly Mazyck and Urmi Shah are associates; Bronwen Manby is a consultant. William Carmichael is the chair of the advisory committee and Alice Brown is the vice-chair. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Janet Fleischman, Washington representative of Human Rights Watch/Africa. It is based on three fact-finding missions to Senegal - - in May-June 1990, February-March 1991, and October-November 1993 -- as well as numerous interviews conducted in Paris, New York, and Washington. Human Rights Watch/Africa gratefully acknowledges the following staff members who assisted with editing and producing this report: Abdullahi An-Na'im; Karen Sorensen; and Kim Mazyck. In addition, we would like to thank Rakiya Omaar and Alex de Waal for their contributions. Most importantly, we express our sincere thanks to the many Mauritanians, most of whom must remain nameless for their own protection and that of their families, who provided invaluable assistance throughout this project. -

Food Insecurity and Complex Emergency

FACT SHEET #16, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 14, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS In general, food security conditions in most of the Sahel have stabilized and are expected to improve to No Acute Food Insecurity—Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) 1—in October and November, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nonetheless, FEWS NET notes that ongoing flooding and increasing numbers of desert locusts remain significant threats and could reduce this year’s agricultural production in some areas. Continuing insecurity and related displacement could also prompt above- average food assistance needs in Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger in early 2013. To date, floods—resulting from heavy seasonal rains in parts of the Sahel—have affected or displaced approximately 21,000 people throughout Burkina Faso, 25,000 people in northern Cameroon, 500,000 people in Chad, 9,000 people in Mali, and 527,000 people in Niger, according to international media and relief agency sources. In Senegal, flooding triggered by severe rainfall since mid-August has affected more than 260,000 people, according to a recent U.N. rapid assessment of the country’s flooded areas. On September 13, U.S. Ambassador Lewis A. Lukens declared a disaster due to the effects of the floods. In response, USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) is providing $50,000 to Catholic Relief Services (CRS) for flood-relief activities in affected communities, including a hygiene awareness campaign and the provision of supplies such as mosquito nets, boots, and pumps to help remove standing water. -

Sahel Food Security and Complex Emergency

FACT SHEET #17, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY This is the final Sahel fact sheet for FY 2012. KEY DEVELOPMENTS Nearly one year since the onset of the food insecurity and nutrition crisis in the Sahel, food security conditions have stabilized and are expected to improve to No Acute Food Insecurity—Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) 1—in most areas by November due in part to positive agricultural production forecasts, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nonetheless, FEWS NET notes that recent flooding and increasing numbers of desert locusts remain significant threats and could reduce this year’s agricultural output in some areas. Ongoing insecurity in Mali and related displacement could also result in continuing above- average humanitarian assistance needs in parts of Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger through late 2012. The rate at which Malians are fleeing to neighboring countries recently slowed, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In August, the number of new arrivals in Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Niger declined by 61 percent compared to the preceding month, decreasing from an estimated 60,000 people per month to approximately 23,500 people per month. In mid-September, the Mali Protection Cluster—the coordinating body for humanitarian protection activities in the country—revised the estimated number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Mali from 174,000 to 118,795, reflecting a decrease of 32 percent. Due to access challenges in the north, the new estimates may not represent the full number of IDPs in Mali, and the cluster continues working to obtain a more comprehensive count of IDPs. -

Mauritania Country Study

area handbook series Mauritania country study Mauritania a country study Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Robert E. Handloff Research Completed December 1987 On the cover: Pastoralists near 'Ayoun el 'Atrous Second Edition, First Printing, 1990. Copyright ®1990 United States Government as represented by the Secretary of the Army. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mauritania: A Country Study. Area handbook series, DA pam 550-161 "Research completed June 1988." Bibliography: pp. 189-200. Includes index. Supt. of Docs. no. : D 101.22:000-000/987 1. Mauritania I. Handloff, Robert Earl, 1942- . II. Curran, Brian Dean. Mauritania, a country study. III. Library of Congress. Federal Research Division. IV. Series. V. Series: Area handbook series. DT554.22.M385 1990 966.1—dc20 89-600361 CIP Headquarters, Department of the Army DA Pam 550-161 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This volume is one in a continuing series of books now being prepared by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Con- gress under the Country Studies—Area Handbook Program. The last page of this book lists the other published studies. Most books in the series deal with a particular foreign country, describing and analyzing its political, economic, social, and national security systems and institutions, and examining the interrelation- ships of those systems and the ways they are shaped by cultural factors. Each study is written by a multidisciplinary team of social scientists. The authors seek to provide a basic understanding of the observed society, striving for a dynamic rather than a static portrayal. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building MAURITANIA

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building MAURITANIA Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Version 1.1) 1 Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 18/05/2018 Ce.S.I. Overall structure and first draft 1.1 30/11/2018 Ce.S.I. Final version LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER 1.1 2 Mauritania Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Alessandra Giada Dibenedetto Ce.S.I. Centre for International Studies Within the framework of LET4CAP and with the financial support to the Internal Security Fund of the EU LET4CAP aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP…. All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1 Country in Brief 1.2 Modern and Contemporary History of Mauritania 1.3 Geography 1.4 Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6 Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7 Health 1.8 Education and Literacy 1.9 Country Economy 2. -

An Assessment of the Potential Country

AN ASSESSMENT OF THE POTENTIAL FOR PEACE CORPS--USAID--HOS1 COUNTRY COOPERATION IN SOCIAL FORESTRY PROJECTS MAURITANIA A Report Prepared by Arlene Blade.' -/ and Frederick J. Conway -2/ Office of Program Development Peace Corps Washington, DC 20525 June 1981 1/11804 Rocking Horse Road Rockville, MD 20852 .2/3725 Macomb Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MAURITANIA PASA REPORT I. HOST COUNTRY The forestry service of Mauritania is called the Protection of Nature Service, a branch of the Ministry of Rural Development. The Protection of Nature Service has few forestry agents and material and financial resources are scarce. The Service has little experience in resource management extension work, though it intends to increase this kind of activity, in part through a major project with AID. In recent years, Mauritania has experienced serious pressures on natural resources, especially along the Senegal River. This is due in large part to population migration and conflicting land use patterns between agricultural and pastoral people. The Government of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania (GIRM) has received assistance in natural resource projects from various donors. The Lutheran World Relief has stabilized dunes and built a greenbelt around Nouakchott. The West African Economic Community is providing funds for nursery development. AID began a Renewable Resources Management Project in 1978. Rural people in Mauritania are interested in tree planting and establishing soil conservation practices. II. PEACE CORPS/MAURITANIA (PC/M) Peace Corps is growing rapidly in Mauritania ind now has 33 volunteers. There are health and agriculture programs, with a forestry program to be added in 1982. -

FOOD INSECURITY and COMPLEX EMERGENCY This Is the Final Sahel Fact Sheet for FY 2012

FACT SHEET #17, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY This is the final Sahel fact sheet for FY 2012. KEY DEVELOPMENTS Nearly one year since the onset of the food insecurity and nutrition crisis in the Sahel, food security conditions have stabilized and are expected to improve to No Acute Food Insecurity—Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) 1—in most areas by November due in part to positive agricultural production forecasts, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nonetheless, FEWS NET notes that recent flooding and increasing numbers of desert locusts remain significant threats and could reduce this year’s agricultural output in some areas. Ongoing insecurity in Mali and related displacement could also result in continuing above- average humanitarian assistance needs in parts of Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger through late 2012. The rate at which Malians are fleeing to neighboring countries recently slowed, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In August, the number of new arrivals in Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Niger declined by 61 percent compared to the preceding month, decreasing from an estimated 60,000 people per month to approximately 23,500 people per month. In mid-September, the Mali Protection Cluster—the coordinating body for humanitarian protection activities in the country—revised the estimated number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Mali from 174,000 to 118,795, reflecting a decrease of 32 percent. Due to access challenges in the north, the new estimates may not represent the full number of IDPs in Mali, and the cluster continues working to obtain a more comprehensive count of IDPs. -

Mauritania Annual Country Report 2018 Country Strategic Plan 2018 - 2018 ACR Reading Guidance Table of Contents Summary

SAVING LIVES CHANGING LIVES Mauritania Annual Country Report 2018 Country Strategic Plan 2018 - 2018 ACR Reading Guidance Table of contents Summary . 4 Context and Operations . 7 Programme Performance - Resources for Results . 9 Programme Performance . 10 Strategic Outcome 01 . 10 Strategic Outcome 02 . 10 Strategic Outcome 03 . 12 Strategic Outcome 04 . 12 Strategic Outcome 05 . 13 Strategic Outcome 06 . 14 Cross-cutting Results . 16 Progress towards gender equality . 16 Protection . 16 Accountability to affected populations . 17 Environment . 17 Fighting drought . 19 Figures and Indicators . 20 Data Notes . 20 Beneficiaries by Age Group . 23 Beneficiaries by Residence Status . 24 Annual Food Distribution (mt) . 24 Annual CBT and Commodity Voucher Distribution (USD) . 25 Output Indicators . 26 Outcome Indicators . 29 Cross-cutting Indicators . 63 Progress towards gender equality . 63 Mauritania | Annual country report 2018 2 Protection . 64 Accountability to affected populations . 64 Mauritania | Annual country report 2018 3 Summary Launching its Interim Country Strategic Plan in 2018, WFP started to WFP intensified its efforts to build the national preparedness and response progressively assume a more enabling role to support the Government of capacities of the Mauritanian government, and enhanced coordination among Mauritania in establishing the national Adaptive Social Protection System (ASP). A emergency and disaster risk reduction actors. In addition, WFP further key government priority, this system is considered an important investment in strengthened strategic partnerships with international and national the humanitarian-development nexus given its focus on the linkages between organizations for integrated planning and technical assistance, augmenting peace, security and migration. Furthermore, the ASP is an essential step in programme quality, institutional learning and efficiency gains.