Rapport Pastoralisme Eng 2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER

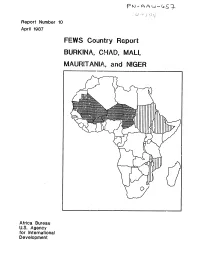

Report Number 10 April 1987 FEWS Country Report BURKINA, CHAD, MALI, MAURITANIA, and NIGER Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development Summary Map __ Chad lMurltanl fL People displaced by fighting High percentage of population have bothL.J in B.E.T. un~tfood needsa nd no source of income - High crop oss cobied with WESTERN Definite increases in retes of malnutrition at CRS centers :rom scarce mrket and low SAHARA .ct 1985 through Nov 196 ,cash income Areas with high percentage MA RTAI of vulnerable LIBYA MAU~lAN~A/populations / ,,NIGER SENEGAL %.t'"S-"X UIDA Areas at-risk I/TGI IEI BurkinaCAMEROON Areas where grasshoppers r Less than 50z of food needs met combined / CENTRAL AFRICAN would have worst impact Fi with absence of government stocks REPLTL IC if expected irdestat ions occur W Less than r59 of food needs met combined ith absence of government stocks FEYIS/PWA. April 1987 Famine Early Warning System Country Report BURKINA CHAD MALI MAURITANIA NIGER Populations Under Duress Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. April 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 2 Burkina 6 Chad 9 Mali 12 Mauritania 18 Niger 2f FiAures 3 Map 2 Burkina, Grain Supply and OFNACER Stocks 4 Table I Burkina, Production and OFNACER Stocks 6 Figure I Chad, Prices of Staple Grains in N'Djamcna 7 Map 3 Chad, Populations At-Risk 10 Table 2 Mali, Free Food Distribution Plan for 1987 II Map 4 Mali, Population to Receive Food Aid 12 Figure 2 Mauritania, Decreasing -

Appraisal Report

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND MAU/PAAL/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT AND RANGE MANAGEMENT ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA NB: This document contains errata or corrigenda (see Annexes) COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDN NORTH REGION SEPTEMBER 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONENTS Page PROJECT BRIEF, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, PROJECT MATRIX, CURRENCY i-ix EQUIVALENTS, LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF TABLES, LIST OF ANNEXES, COMPARATIVE SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS 1. ORIGIN AND PROJECT BACKGROUND 1 2. THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 1 2.1 Main Features 1 2.2 Natural Resources and Products 2 2.3 Land Tenure System 2 2.4 Rural Poverty 2 3. THE LIVESTOCK SUB-SECTOR 3 3.1 Importance of the Sub-Sector 3 3.2 Livestock Systems 3 3.3 Institutions of Sub-sector 4 3.4 Sub-sector Constraints 6 3.5 Government Policy and Strategy 7 3.6 Donor Interventions 7 4. THE PROJECT 8 4.1 Project Design and Rationale 8 4.2 Project Impact Area and Beneficiaries 8 4.3 Strategic Context 9 4.4 Project Objective 9 4.5 Project Description 9 4.6 Production, Marketing and Prices 13 4.7 Environmental Impact 13 4.8 Project Costs 14 4.9 Sources of Finance 15 5. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 16 5.1 Executing Agency 16 5.2 Institutional Provisions 18 5.3 Implementation and Supervision Schedule 19 5.4 Provisions Relating to the Procurement of Goods and Services 19 5.5 Provisions Relating to Disbursement 21 5.6 Monitoring and Evaluation 21 5.7 Financial Statements and Audit 22 5.8 Aid Coordination 22 TABLE OF CONTENTS (cont’d) Page 6. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

Mauritania Validation Initial Assessment

EITI International Secretariat November 2016 Validation of Mauritania Report on initial data collection and stakeholder consultation Website www.eiti.org Email [email protected] Telephone +47 22 20 08 00 Fax +47 22 83 08 02 Address EITI International Secretariat, Ruseløkkveien 26, 0251 Oslo, Norway 2 Validation of Mauritania: Report on initial data collection and stakeholder consultation Abbreviations AfDB African Development Bank BCM Banque Centrale de Mauritanie BEPS Base Erosion and Profit Shifting BO Beneficial ownership Bpd Barrels Per Day BTU British thermal unit CdC Cour des Comptes (Court of Counts) CIT Corporate Income Tax CNITIE National EITI Committee CSO Civil Society Organisation DCMG Directorate of the Mining Cadastre and Geology DGD Directorate General of Customs DGH Directorate General of Hydrocarbons DGI Directorate General of Tax DGTCP Directorate General of Treasury and Public Accounts EU European Union FNRH National Hydrocarbon Revenue Fund GDP Gross Domestic Product GFS Government Finance Statistics GiZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit IGF General Inspectorate of Finance IMF International Monetary Fund IRM Islamic Republic of Mauritania LNG Liquefied Natural Gas MAED Ministry of Economic Affairs and Development MDTF Multi-Donor Trust Fund MEDD Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development MEF Ministry of Economy and Finance MPEM Ministry of Petroleum, Energy and Mines MRO Mauritanian Ouguiya MSG Multi-Stakeholder Group NGO Non-Governmental Organisation PEP Politically Exposed Person -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 12606-MAU Mauritania Country EnvironmentalStrategy Paper Public Disclosure Authorized June30, 1994 Africa Region Sahelian Departnient Public Disclosure Authorized U Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized I ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AMEXTIPE Mauritanian Agency for Public Works AgenceMauritanienne d'Execution des and Employment Travauxdlnteret Publicet pour l'Emploi CESP CountryEnvironumental Strategy Paper Documentde Strategie Environnementale CNEA NationalCenter for AlternativeEnergy Cellule Nationale des Energies Alternatives DEAR Departmentof Environmentand Rural Direction de lEnvironnement et de Planning l'Am6nagementRural EC EuropeanCommunity CommunauteEuropeene GEF GlobalEnvironment Facility Fondspour l'EnvironnementMondial IUCN WorldConservation Union Union Mondialepour la Nature LPG LiquidPropane Gas MDRE Ministry of Rural Development and Minist&re du Developpement et de Envirorunent l'Environnement MHE Ministryof Water and Energy Ministere de lHydraulique et de lEnergie MS Ministryof Health Ministerede la Sante NEAP NationalEnvironmental Action Plan Plan dAction National pour l'Environnement NRM Natural ResourceManagement Gestiondes RessourcesNaturelles OMVS Organization for the Development of Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur the SenegalRiver Valley du FleuveSenegal PAs PastoralAssociations AssociationsPastorales UNCED United Nations Conference on Environmentand Development UNDP United Nations Development Programmedes Nations Unies pour la Programme Developpement UNSO -

Mauritania's Campaign of Terror: State-Sponsored Repression of Black Africans

MAURITANIA'S CAMPAIGN OF TERROR State-Sponsored Repression of Black Africans Human Rights Watch/Africa (formerly Africa Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $ Washington $ Los Angeles $ London Copyright 8 April 1994 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94-75822 ISBN: 1-56432-133-9 Human Rights Watch/Africa (formerly Africa Watch) Human Rights Watch/Africa is a non-governmental organization established in 1988 to monitor promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Africa. Abdullahi An- Na'im is the director; Janet Fleischman is the Washington representative; Karen Sorensen, Alex Vines, and Berhane Woldegabriel are research associates; Kimberly Mazyck and Urmi Shah are associates; Bronwen Manby is a consultant. William Carmichael is the chair of the advisory committee and Alice Brown is the vice-chair. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Janet Fleischman, Washington representative of Human Rights Watch/Africa. It is based on three fact-finding missions to Senegal - - in May-June 1990, February-March 1991, and October-November 1993 -- as well as numerous interviews conducted in Paris, New York, and Washington. Human Rights Watch/Africa gratefully acknowledges the following staff members who assisted with editing and producing this report: Abdullahi An-Na'im; Karen Sorensen; and Kim Mazyck. In addition, we would like to thank Rakiya Omaar and Alex de Waal for their contributions. Most importantly, we express our sincere thanks to the many Mauritanians, most of whom must remain nameless for their own protection and that of their families, who provided invaluable assistance throughout this project. -

Food Insecurity and Complex Emergency

FACT SHEET #16, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 14, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS In general, food security conditions in most of the Sahel have stabilized and are expected to improve to No Acute Food Insecurity—Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) 1—in October and November, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nonetheless, FEWS NET notes that ongoing flooding and increasing numbers of desert locusts remain significant threats and could reduce this year’s agricultural production in some areas. Continuing insecurity and related displacement could also prompt above- average food assistance needs in Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger in early 2013. To date, floods—resulting from heavy seasonal rains in parts of the Sahel—have affected or displaced approximately 21,000 people throughout Burkina Faso, 25,000 people in northern Cameroon, 500,000 people in Chad, 9,000 people in Mali, and 527,000 people in Niger, according to international media and relief agency sources. In Senegal, flooding triggered by severe rainfall since mid-August has affected more than 260,000 people, according to a recent U.N. rapid assessment of the country’s flooded areas. On September 13, U.S. Ambassador Lewis A. Lukens declared a disaster due to the effects of the floods. In response, USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) is providing $50,000 to Catholic Relief Services (CRS) for flood-relief activities in affected communities, including a hygiene awareness campaign and the provision of supplies such as mosquito nets, boots, and pumps to help remove standing water. -

Widespread Distribution of Plasmodium Vivax Malaria in Mauritania on the Interface of the Maghreb and West Africa Hampâté Ba1*, Craig W

Ba et al. Malar J (2016) 15:80 DOI 10.1186/s12936-016-1118-8 Malaria Journal RESEARCH Open Access Widespread distribution of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Mauritania on the interface of the Maghreb and West Africa Hampâté Ba1*, Craig W. Duffy2, Ambroise D. Ahouidi3, Yacine Boubou Deh1, Mamadou Yero Diallo1, Abderahmane Tandia1 and David J. Conway2* Abstract Background: Plasmodium vivax is very rarely seen in West Africa, although specific detection methods are not widely applied in the region, and it is now considered to be absent from North Africa. However, this parasite species has recently been reported to account for most malaria cases in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, which is a large country at the interface of sub-Saharan West Africa and the Maghreb region in northwest Africa. Methods: To determine the distribution of malaria parasite species throughout Mauritania, malaria cases were sampled in 2012 and 2013 from health facilities in 12 different areas. These sampling sites were located in eight major administrative regions of the country, within different parts of the Sahara and Sahel zones. Blood spots from finger- prick samples of malaria cases were processed to identify parasite DNA by species-specific PCR. Results: Out of 472 malaria cases examined, 163 (34.5 %) had P. vivax alone, 296 (62.7 %) Plasmodium falciparum alone, and 13 (2.8 %) had mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax infection. All cases were negative for Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale. The parasite species distribution showed a broad spectrum, P. vivax being detected at six of the different sites, in five of the country’s major administrative regions (Tiris Zemmour, Tagant, Brakna, Assaba, and the capital Nouakchott). -

Sahel Food Security and Complex Emergency

FACT SHEET #17, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY This is the final Sahel fact sheet for FY 2012. KEY DEVELOPMENTS Nearly one year since the onset of the food insecurity and nutrition crisis in the Sahel, food security conditions have stabilized and are expected to improve to No Acute Food Insecurity—Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) 1—in most areas by November due in part to positive agricultural production forecasts, according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nonetheless, FEWS NET notes that recent flooding and increasing numbers of desert locusts remain significant threats and could reduce this year’s agricultural output in some areas. Ongoing insecurity in Mali and related displacement could also result in continuing above- average humanitarian assistance needs in parts of Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger through late 2012. The rate at which Malians are fleeing to neighboring countries recently slowed, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In August, the number of new arrivals in Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Niger declined by 61 percent compared to the preceding month, decreasing from an estimated 60,000 people per month to approximately 23,500 people per month. In mid-September, the Mali Protection Cluster—the coordinating body for humanitarian protection activities in the country—revised the estimated number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Mali from 174,000 to 118,795, reflecting a decrease of 32 percent. Due to access challenges in the north, the new estimates may not represent the full number of IDPs in Mali, and the cluster continues working to obtain a more comprehensive count of IDPs. -

FEWS Country Reports BURKINA, ETHIOPIA, and MAURITANIA

Report Number 18 December 1987 FEWS Country Reports BURKINA, ETHIOPIA, and MAURITANIA Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for Internationa, Development FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM This is the eighteenth in a series of monthly reports on Burkina, Ethiopia; Early Warning System and Mauritania issued by the Famine (FEWS). It is designed to provide decisionm%kers existing and potential nutritior, with current information and analysis on emergency situations. Each situation identified geographical extent and the is described in terms ,f number of people involved, or at-risk, and the proximate causes insofar as they have been discerned. Use of tie term "at-risk" t) identify vulnerable populations isproblematic tion exists. Yet, since no generally agreed upon defini- it is necessary to identify or "target" populttions appropriate forms and levels in-need or "at-risk" in order to determine of intervention. Thus for tilepresent, until a better usage can be found, FEWS reports will employ the term "at-risk" to mean.. .. those persons lacking sufficient food, or resourcs lo acquire sufficient fo-d, to crisis (i.e., a progre.sive deterioration avert a nutritional in their health or nutiitional condition below who, as a result, reCluire specific the status quo), and intervention to avoid a life-threatening situation. Perhaps of most importance to decisionmakers, the FEWS effort highlights the situation, hopefuu!ly with enough process underlying the deteriorating specificity and forewarning to permit alternative examined and implementea. Food intervention strategies to be assistance strategies are key to famine avoidance. vention can be of majc-r importance both However, other types of inter in the short-term and in the long run, including storage, medical, transport, eccnomic development policy change, etc. -

Mauritania Country Study

area handbook series Mauritania country study Mauritania a country study Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Robert E. Handloff Research Completed December 1987 On the cover: Pastoralists near 'Ayoun el 'Atrous Second Edition, First Printing, 1990. Copyright ®1990 United States Government as represented by the Secretary of the Army. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mauritania: A Country Study. Area handbook series, DA pam 550-161 "Research completed June 1988." Bibliography: pp. 189-200. Includes index. Supt. of Docs. no. : D 101.22:000-000/987 1. Mauritania I. Handloff, Robert Earl, 1942- . II. Curran, Brian Dean. Mauritania, a country study. III. Library of Congress. Federal Research Division. IV. Series. V. Series: Area handbook series. DT554.22.M385 1990 966.1—dc20 89-600361 CIP Headquarters, Department of the Army DA Pam 550-161 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This volume is one in a continuing series of books now being prepared by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Con- gress under the Country Studies—Area Handbook Program. The last page of this book lists the other published studies. Most books in the series deal with a particular foreign country, describing and analyzing its political, economic, social, and national security systems and institutions, and examining the interrelation- ships of those systems and the ways they are shaped by cultural factors. Each study is written by a multidisciplinary team of social scientists. The authors seek to provide a basic understanding of the observed society, striving for a dynamic rather than a static portrayal. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building MAURITANIA

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building MAURITANIA Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Version 1.1) 1 Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 18/05/2018 Ce.S.I. Overall structure and first draft 1.1 30/11/2018 Ce.S.I. Final version LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER 1.1 2 Mauritania Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Alessandra Giada Dibenedetto Ce.S.I. Centre for International Studies Within the framework of LET4CAP and with the financial support to the Internal Security Fund of the EU LET4CAP aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP…. All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1 Country in Brief 1.2 Modern and Contemporary History of Mauritania 1.3 Geography 1.4 Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6 Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7 Health 1.8 Education and Literacy 1.9 Country Economy 2.