Prokofiev's Early Solo Piano Music: Context, Influences, Forms, Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perfect Mix Getting Engaged in College

05 07 10 | reportermag.com GETTING ENGAGED IN COLLEGE The other kind of RIT Rings. THE PERFECT MIX Remember: intro, rising action, climax, denouement and conclusion. ROADTRIP TO THE FUTURE Four men. Four cities. One mission. EDITOR’S NOTE TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 07 10 | VOLUME 59 | ISSUE 29 EDITOR IN CHIEF Madeleine Villavicencio | [email protected] My Innovative Mixtape MANAGING EDITOR Emily Mohlmann Every few weeks or so, I abandon the “shuffle play all” function on my MP3 player, turn off Genius on | [email protected] iTunes, and make a playlist. I spend hours listening to track after track, trimming down the set list and COPY EDITOR Laura Mandanas attempting to get the transitions just right. Sometimes, it just comes together; other times, I just can’t | [email protected] quite get it right. But one thing’s for certain: each mix is a reflection of who I am at the time of its creation. NEWS EDITOR Emily Bogle And if it’s good enough and means something, I’ll share it with someone special. | [email protected] LEISURE EDITOR Alex Rogala It crossed my mind to share a complete and perfected mix, but I decided that would take away from its | [email protected] original value. Instead, I’ve decided to share something unfinished and challenge you to help me find the FEATURES EDITOR John Howard perfect mix. Add or cut tracks as you please, and jumble them up as you see fit. And when you think you’ve | [email protected] got it, send that final track list my way. -

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2015 The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók David B. Hill James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, David B., "The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók" (2015). Dissertations. 38. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill A document submitted to the graduate faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2015 ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…iii! ! Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...iv! ! Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1! ! PART!I:!SIMILARITIES!SHARED!BY!THE!TWO!NATIONLISTIC!COMPOSERS! ! A.!Origins…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! B.!Ties!to!Hungary…………………………………………………………………………………………...…..9! -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

There's Even More to Explore!

Background artwork: SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UCHICAGO LIBRARY Kaplan and Fridkin, Agit No. 2 MUSIC THEATER ART MUSIC THEATER LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC / FILM LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC University of Chicago Presents University Theater/Theater and Performance Studies The University of Chicago Library Symphony Center Presents Goodman Theatre University of Chicago Presents Roosevelt University Rockefeller Chapel University of Chicago Presents TOKYO STRING QUARTET THEATER 24 PLAY SERIES: GULAG ART Orchestra Series CHEKHOv’S THE SEAGULL LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN PAciFicA QUARTET: 19TH ANNUAL SILENT FiLM LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN BY MARiiNskY ORCHESTRA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 A CLOUD WITH TROUSERS THROUGH DECEMBER 2010 OCTOber 16 – NOVEMBER 14, 2010 BY PACIFICA QUARTET SHOSTAKOVICH CYCLE WITH ORGAN AccomPANimENT: MAsumi RosTAD, VioLA, AND (FORMERLY KIROV ORCHESTRA) Mandel Hall, 1131 East 57th Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2010, 8 PM The Joseph Regenstein Library, 170 North Dearborn Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 17, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS AMY BRIGGS, PIANO th nd chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 First Floor Theater, Reynolds Club, 1100 East 57 Street, 2 Floor Reading Room Valery Gergiev, conductor Goodmantheatre.org, 312.443.3800 Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 31, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM Jay Warren, organ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2 PM 5706 South University Avenue Lib.uchicago.edu Denis Matsuev, piano Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2010, 8 PM Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street Mozart: Quartet in C Major, K. 575 As imperialist Russia was falling apart, playwright Anton SUNDAY JANUARY 30, 2011, 2 AND 7 PM ut.uchicago.edu TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2010, 8 PM Rockefeller Chapel, 5850 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 Lera Auerbach: Quartet No. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR HARRY JOSEPH GILMORE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 2003 Copyright 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Pennsylvania Carnegie Institute of Technology (Carnegie Mellon University) University of Pittsburgh Indiana University Marriage Entered the Foreign Service in 1962 A,100 Course Ankara. Turkey/ 0otation Officer1Staff Aide 1962,1963 4upiter missiles Ambassador 0aymond Hare Ismet Inonu 4oint US Military Mission for Aid to Turkey (4USMAT) Turkish,US logistics Consul Elaine Smith Near East troubles Operations Cyprus US policy Embassy staff Consular issues Saudi isa laws Turkish,American Society Internal tra el State Department/ Foreign Ser ice Institute (FSI)7 Hungarian 1963,1968 9anguage training Budapest. Hungary/ Consular Officer 1968,1967 Cardinal Mindszenty 4anos Kadar regime 1 So iet Union presence 0elations Ambassador Martin Hillenbrand Israel Economy 9iberalization Arab,Israel 1967 War Anti,US demonstrations Go ernment restrictions Sur eillance and intimidation En ironment Contacts with Hungarians Communism Visa cases (pro ocations) Social Security recipients Austria1Hungary relations Hungary relations with neighbors 0eligion So iet Mindszenty concerns Dr. Ann 9askaris Elin OAShaughnessy State Department/ So iet and Eastern Europe EBchange Staff 1967,1969 Hungarian and Czech accounts Operations Scientists and Scholars eBchange programs Effects of Prague Spring 0elations -

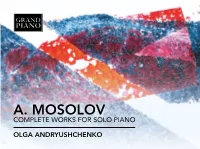

A. Mosolov Complete Works for Solo Piano

A. MOSOLOV COMPLETE WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO OLGA ANDRYUSHCHENKO 1 ALEXANDER MOSOLOV (1900-1973) COMPLETE WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO OLGA ANDRYUSHCHENKO, piano Catalogue number: GP703-04 Recording Dates: 19-22 February 2015 Recording Venue: CMS Studio, Moscow, Russia (CD1) Sovetskij Kompositor, Moscow (1 and 5), Universal Edition, Wien (2) Triton, Leningrad (1928) (3-4) (CD2) Sovetskij Kompositor, Moscow (1 and 3) Universal Edition, Wien (2) Producer and Editor: Galina Katunina Mastering Engineer: Slava Poprugin Engineer: Sergey Solodovnikov Piano Technician: Artjom Deev Piano: Steinway D Booklet Notes: Anthony Short German translation by Cris Posslac Artist photograph: Nicola Christov Composer portrait: Inna Barsova Cover Art: Tony Price: Moissac Abstract Study 4 www.tonyprice.org 2 CD 1 1 PIANO SONATA NO. 1 IN C MINOR, OP. 3 (1924) 10:55 2 NOCTURNES, OP. 15 (1925-26) 06:56 2 No. 1 Elegiaco, poco stentato 03:28 3 No. 2 Adagio 03:28 3 SMALL PIECES, OP. 23A (1927) 02:25 4 No. 1 00:55 5 No. 2 00:47 6 No. 3 00:43 2 DANCES, OP. 23B (1927) 04:17 7 No. 1 Allegro molto, sempre marcato 02:02 8 No. 2 Allegretto 02:15 PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN B MINOR, OP. 4 “FROM OLD NOTEBOOKS” (1923-24) 23:35 9 I. Sonata 10:28 0 II. Adagio 06:38 ! III. Final 06:29 TOTAL TIME: 48:06 3 CD 2 1 PIANO SONATA NO. 4, OP. 11 (1925) 11:46 TURKMENIAN NIGHTS – PHANTASY FOR PIANO (1929) 11:41 2 I. Andante con moto 04:07 3 II. Lento 05:15 4 III. -

Abstracts Euromac2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014

Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens 2014 Euro Leuven MAC Eighth European Music Analysis Conference 17-20 September 2014 Abstracts EuroMAC2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014 www.euromac2014.eu EuroMAC2014 Abstracts Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier, Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens Graphic Design & Layout: Klaas Coulembier Photo front cover: © KU Leuven - Rob Stevens ISBN 978-90-822-61501-6 A Stefanie Acevedo Session 2A A Yale University [email protected] Stefanie Acevedo is PhD student in music theory at Yale University. She received a BM in music composition from the University of Florida, an MM in music theory from Bowling Green State University, and an MA in psychology from the University at Buffalo. Her music theory thesis focused on atonal segmentation. At Buffalo, she worked in the Auditory Perception and Action Lab under Peter Pfordresher, and completed a thesis investigating metrical and motivic interaction in the perception of tonal patterns. Her research interests include musical segmentation and categorization, form, schema theory, and pedagogical applications of cognitive models. A Romantic Turn of Phrase: Listening Beyond 18th-Century Schemata (with Andrew Aziz) The analytical application of schemata to 18th-century music has been widely codified (Meyer, Gjerdingen, Byros), and it has recently been argued by Byros (2009) that a schema-based listening approach is actually a top-down one, as the listener is armed with a script-based toolbox of listening strategies prior to experiencing a composition (gained through previous style exposure). This is in contrast to a plan-based strategy, a bottom-up approach which assumes no a priori schemata toolbox. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain.