13—Glacial and Glaciofluvial Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

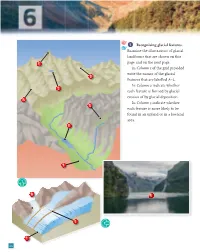

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Quarrernary GEOLOGY of MINNESOTA and PARTS of ADJACENT STATES

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman ,Wilbur, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director P~ofessional Paper 161 . QUArrERNARY GEOLOGY OF MINNESOTA AND PARTS OF ADJACENT STATES BY FRANK LEVERETT WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY FREDERICK w. SARDE;30N Investigations made in cooperation with the MINNESOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1932 ·For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ _ 1 Wisconsin red drift-Continued. Introduction _____________________________________ _ 1 Weak moraines, etc.-Continued. Scope of field work ____________________________ _ 1 Beroun moraine _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 47 Earlier reports ________________________________ _ .2 Location__________ _ __ ____ _ _ __ ___ ______ 47 Glacial gathering grounds and ice lobes _________ _ 3 Topography___________________________ 47 Outline of the Pleistocene series of glacial deposits_ 3 Constitution of the drift in relation to rock The oldest or Nebraskan drift ______________ _ 5 outcrops____________________________ 48 Aftonian soil and Nebraskan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Striae _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 48 Kansan drift _____________________________ _ 5 Ground moraine inside of Beroun moraine_ 48 Yarmouth beds and Kansan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Mille Lacs morainic system_____________________ 48 Pre-Illinoian loess (Loveland loess) __________ _ 6 Location__________________________________ -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Crag-And-Tail Features on the Amundsen Sea Continental Shelf, West Antarctica

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on November 30, 2016 Crag-and-tail features on the Amundsen Sea continental shelf, West Antarctica F. O. NITSCHE1*, R. D. LARTER2, K. GOHL3, A. G. C. GRAHAM4 & G. KUHN3 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Am Alten Hafen 26, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 4College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) On parts of glaciated continental margins, especially the inner leads to its characteristic tapering and allows formation of the sec- shelves around Antarctica, grounded ice has removed pre-existing ondary features. Multiple, elongated ridges in the tail could be sedimentary cover, leaving subglacial bedforms on eroded sub- related to the unevenness of the top of the ‘crags’. Secondary, strates (Anderson et al. 2001; Wellner et al. 2001). While the smaller crag-and-tail features might reflect variations in the under- dominant subglacial bedforms often follow a distinct, relatively lying substrate or ice-flow dynamics. uniform pattern that can be related to overall trends in palaeo- While the length-to-width ratio of crag-and-tail features in this ice flow and substrate geology (Wellner et al. 2006), others are case is much lower than for drumlins or elongate lineations, the more randomly distributed and may reflect local substrate varia- boundary between feature classes is indistinct. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

Glacial Processes and Landforms-Transport and Deposition

Glacial Processes and Landforms—Transport and Deposition☆ John Menziesa and Martin Rossb, aDepartment of Earth Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada; bDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Introduction 2 2 Towards deposition—Sediment transport 4 3 Sediment deposition 5 3.1 Landforms/bedforms directly attributable to active/passive ice activity 6 3.1.1 Drumlins 6 3.1.2 Flutes moraines and mega scale glacial lineations (MSGLs) 8 3.1.3 Ribbed (Rogen) moraines 10 3.1.4 Marginal moraines 11 3.2 Landforms/bedforms indirectly attributable to active/passive ice activity 12 3.2.1 Esker systems and meltwater corridors 12 3.2.2 Kames and kame terraces 15 3.2.3 Outwash fans and deltas 15 3.2.4 Till deltas/tongues and grounding lines 15 Future perspectives 16 References 16 Glossary De Geer moraine Named after Swedish geologist G.J. De Geer (1858–1943), these moraines are low amplitude ridges that developed subaqueously by a combination of sediment deposition and squeezing and pushing of sediment along the grounding-line of a water-terminating ice margin. They typically occur as a series of closely-spaced ridges presumably recording annual retreat-push cycles under limited sediment supply. Equifinality A term used to convey the fact that many landforms or bedforms, although of different origins and with differing sediment contents, may end up looking remarkably similar in the final form. Equilibrium line It is the altitude on an ice mass that marks the point below which all previous year’s snow has melted. -

Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Summer school in Glaciology, McCarthy 5-15 June 2018 Regine Hock Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks Glacier Mass Balance This summary follows the terminology proposed by Cogley et al. (2011) 1. Introduction: Definitions and processes Definition: Mass balance is the change in the mass of a glacier, or part of the glacier, over a stated span of time: t . ΔM = ∫ Mdt t1 The term mass budget is a synonym. The span of time is often a year or a season. A seasonal mass balance is nearly always either a winter balance or a summer balance, although other kinds of seasons are appropriate in some climates, such as those of the tropics. The definition of “year” depends on the measurement method€ (see Chap. 4). The mass balance, b, is the sum of accumulation, c, and ablation, a (the ablation is defined here as negative). The symbol, b (for point balances) and B (for glacier-wide balances) has traditionally been used in studies of surface mass balance of valley glaciers. t . b = c + a = ∫ (c+ a)dt t1 Mass balance is often treated as a rate, b dot or B dot. Accumulation Definition: € 1. All processes that add to the mass of the glacier. 2. The mass gained by the operation of any of the processes of sense 1, expressed as a positive number. Components: • Snow fall (usually the most important). • Deposition of hoar (a layer of ice crystals, usually cup-shaped and facetted, formed by vapour transfer (sublimation followed by deposition) within dry snow beneath the snow surface), freezing rain, solid precipitation in forms other than snow (re-sublimation composes 5-10% of the accumulation on Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica). -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Brief Communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of Ice from a Cirque Glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina

The Cryosphere, 13, 997–1004, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-997-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Brief communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of ice from a cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina Daniel Falaschi1,2, Andreas Kääb3, Frank Paul4, Takeo Tadono5, Juan Antonio Rivera2, and Luis Eduardo Lenzano1,2 1Departamento de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 2Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 3Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, 0371, Norway 4Department of Geography, University of Zürich, Zürich, 8057, Switzerland 5Earth Observation research Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 2-1-1, Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8505, Japan Correspondence: Daniel Falaschi ([email protected]) Received: 14 September 2018 – Discussion started: 4 October 2018 Revised: 15 February 2019 – Accepted: 11 March 2019 – Published: 26 March 2019 Abstract. Among glacier instabilities, collapses of large der of up to several 105 m3, with extraordinary event vol- parts of low-angle glaciers are a striking, exceptional phe- umes of up to several 106 m3. Yet the detachment of large nomenon. So far, merely the 2002 collapse of Kolka Glacier portions of low-angle glaciers is a much less frequent pro- in the Caucasus Mountains and the 2016 twin detachments of cess and has so far only been documented in detail for the the Aru glaciers in western Tibet have been well documented. 130 × 106 m3 avalanche released from the Kolka Glacier in Here we report on the previously unnoticed collapse of an the Russian Caucasus in 2002 (Evans et al., 2009), and the unnamed cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina recent 68±2×106 and 83±2×106 m3 collapses of two ad- in March 2007. -

Inventory of Glaciers, Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential

Asia‐Pacific Network for Global Change Research Inventory of Glaciers, Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) Affected by Global Warming in the Mountains of India, Pakistan and China/Tibet Autonomous Region Final report for APN project 2004-03-CMY-Campbell J. Gabriel Campbell (Ph.D.), Director General International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development G. P. O. Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal, [email protected] The following collaborators worked on this project: Prof. Xin Li (Ph. D.), Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, (CAREERI), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Lanzhou, P. R. China, [email protected] Mr. Gong Tongliang, Bureau of Hydrology Tibet Autonomous Region, Lhasa, P. R. China, [email protected] Dr. Tej Partap. CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh, India, [email protected] Prof. Dr. B. R. Arora, Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG), Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, Dehra Dun, Uttaranchal, India, [email protected] Dr. Badaruddin Soomro, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Inventory of Glaciers and Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) Affected by Global Warming in the Mountains of India, Pakistan and China/Tibet Autonomous Region 2004-03-CMY-Campbell Final Report submitted to APN J. Gabriel Campbell (Ph.D.) Director General, International Centre for Integrated Mountain -

Glaciation in East Africa

GLACIATION IN EAST AFRICA Glaciation: it refers to the overall effect of glaciers on the landscape resulting into both erosional and depositional features Glacier is a thick/large mass of ice of limited width, moving from the area of accumulation (snow field) following pre-existing valleys due to gravity. Or Glacier is an accumulated/compacted mass of ice/snow moving in a restricted channel/valley from a highland to a low land. Glaciers have different names for example mountain glaciers and valley glaciers/alpine glacier. Glaciers move continuously from higher ground to lower ground under the influence of gravity and are enclosed within the valley walls. The action of glacier includes glacier erosion, transportation and deposition. These processes will lead to the formation of glacier scenery. Glaciers in East Africa are only found in high mountainous areas of Kenya, Kilimanjaro and Rwenzori. This is mainly because those mountains (Kenya, Kilimanjaro and Rwenzori) are high above the snow line (4500m). In East Africa glacial activities are limited to a few places, this is due to a number of factors that limit the formation of snow and this include: The latitudinal position of East Africa across or astride the equator hence, the temperatures are generally hot and therefore not conducive for the existence of glacier anywhere and anyhow in East Africa. In East Africa the snowline is very high about 4800m, which only the three highest mountains can reach which explains them having the glacial activities. Snowline is that line where there is permanent snow and ice. It can be at ground level at poles. -

Cirques Have Growth Spurts During Deglacial and Interglacial Periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al Nuclide Inventories in the Central and Eastern Pyrenees Y

Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees Y. Crest, M Delmas, Regis Braucher, Y. Gunnell, M Calvet, A.S.T.E.R. Team To cite this version: Y. Crest, M Delmas, Regis Braucher, Y. Gunnell, M Calvet, et al.. Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees. Geomorphology, Elsevier, 2017, 278, pp.60 - 77. 10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.10.035. hal-01420871 HAL Id: hal-01420871 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01420871 Submitted on 21 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Geomorphology 278 (2017) 60–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Cirques have growth spurts during deglacial and interglacial periods: Evidence from 10Be and 26Al nuclide inventories in the central and eastern Pyrenees Y. Crest a,⁎,M.Delmasa,R.Braucherb, Y. Gunnell c,M.Calveta, ASTER Team b,1: a Univ Perpignan Via-Domitia, UMR 7194 CNRS Histoire Naturelle de l'Homme Préhistorique, 66860 Perpignan Cedex, France b Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS–IRD–Collège de France, UMR 34 CEREGE, Technopôle de l'Environnement Arbois–Méditerranée, BP80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence, France c Univ Lyon Lumière, Department of Geography, UMR 5600 CNRS Environnement Ville Société, 5 avenue Pierre Mendès-France, F-69676 Bron, France article info abstract Article history: Cirques are emblematic landforms of alpine landscapes.