The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

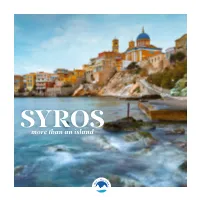

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Civil Affairs Handbook on Greece

Preliminary Draft CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK on GREECE feQfiJtion Thirteen on fcSSLJC HJI4LTH 4ND S 4 N 1 T £ T I 0 N THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE PROVOST MARSHAL GENERAL Preliminary Draft INTRODUCTION Purposes of the Civil Affairs Handbook. International Law places upon an occupying power the obligation and responsibility for establishing government and maintaining civil order in the areas occupied. The basic purposes of civil affairs officers are thus (l) to as- sist the Commanding General of the combat units by quickly establishing those orderly conditions which will contribute most effectively to the conduct of military operations, (2) to reduce to a minimum the human suffering and the material damage resulting from disorder and (3) to create the conditions which will make it possible for civilian agencies to function effectively. The preparation of Civil Affairs Handbooks is a part of the effort of the War Department to carry out this obligation as efficiently and humanely as is possible. The Handbooks do not deal with planning or policy. They are rather ready reference source books of the basic factual information needed for planning and policy making. Public Health and Sanitation in Greece. As a result of the various occupations, Greece presents some extremely difficult problems in health and sanitation. The material in this section was largely prepared by the MILBANK MEMORIAL FUND and the MEDICAL INTELLI- GENCE BRANCH OF THE OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL. If additional data on current conditions can be obtained, it willJse incorporated in the final draft of the handbook for Greece as a whole. -

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3930-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3930-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Greeting ................................................................................... ix Lidija Pliberšek Foreword .................................................................................................. xi Julie Rugg Acknowledgements ................................................................................ xiii List of Illustrations ............................................................................... xvii Introduction ........................................................................................ xxvii Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Part One: Funerary Monuments Inspired by the Art of Antiquity Chapter One ............................................................................................. -

Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19Th-Century Central Balkans

Portland State University PDXScholar International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations International & Global Studies 9-2020 Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans Evguenia Davidova Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/is_fac Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, and the Social History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Davidova, E. (2020). Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 31(1), 48-67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Evguenia Davidova Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans Abstract: Tis article compares the geographic and social mobility of two “lesser known” groups of workers: merchants’ assistants and maidservants. By combining labor mobility, class, and gender as categories of analysis, it suggests that such examples of temporary and return migration opened up new economic possibilities while at the same time reinforcing patriarchal order and increasing social inequality. Such transformative social practice is placed within the broader socio-economic and political fabric of the late Otto man and post-Ottoman Balkans during the “long 19th century.” Key Words: Balkans, commercial networks, domestic servants, labor mobil- ity, migration Troughout the 19th century, the Balkans faced profound economic, social, polit- ical, and cultural changes. -

INFO KIT for Partners

European Solidarity Corps Guide Call 2019, Round 1, European Solidarity Corps - Volunteering Projects REQUIREMENTSWAVES III IN TERMS OF DISSEMINATION AND EXPLOITATION We Are Volos’ EvS III INFO KITGENERAL for partners QUALITATIVE REQUIREMENTS ApplicantsMunicipality of Volos for funding GREECE under the European Solidarity Corps are required to consider dissemination and exploitation KEKPA-DIEK Municipal activitiesEnterprise of Social Protection and Solidarity at the application stage,– during their activity and after the activity has finished. This section gives an overview of theMunicipal Institute of Vo basic requirementscational Training laid down for the European Solidarity Corps. http://www.kekpa.gr Dissemination and exploitation is one of the award criteria on which the application will be assessed. For all project types, Contact KEKPA-DIEKs projects application office: KEKPA-DIEK of the Municipality of Volos, GREECE. 22-26 Proussis str., GRreporting-38446, Nea Ionia VOLOS, Greece. Tel: +30 24210 on the activities61600. Email: carried out and to share the results inside and outside participating organisations will be [email protected] ; [email protected] Contact KEKPArequested-DIEKS coordinator of Volunteering activities at final stage.: Tel: +30 24210 35555. Email: [email protected] VISIBILITY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AND OF THE EUROPEAN SOLIDARITY CORPS Volos, 01.2019 Editing: Spyros Iatropoulos, Sociologist BeneficiariesProject department of KEKPA shall always-DIEK use the European emblem (the 'EU flag') and the name of the European Union spelled out in full in all communication and promotiona1l material. The preferred option to communicate about EU funding through the European Solidarity Corps is to write 'Co-funded by the European Solidarity Corps of the European Union' next to the EU emblem. -

Greek Banking in Constantinople, 1850-1881

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Greek banking in Constantinople, 1850-1881. Exertzoglou, Haris H A The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 to Angelo.. List of contents List of Tables p • I-Ill Abbreviations p • IV Acknowledgements p . V Introduction p.VI-VIII Part I Chapter I:The 19th century Ottoman empire;the economic landscape. -

Elias Petropoulos: a Presentation by John Taylor 7 Shepherds, Brigands, and Irregulars in Nineteenth Century Greece by John S

Jo HELLENIC DIASPORA A Quarterly Review VOL. VIII No. 4 WINTER 1981 Publisher: LEANDROS PAPATHANASIOU Editorial Board: DAN GEORGAKAS PASCHALIS M. '<mom:umEs PETER PAPPAS Y1ANNIS P. ROUBATIS Founding Editor: N1KOS PETROPOULOS The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora air mail; Institutional—$20.00 for one is a quarterly review published by Pella year, $35.00 for two years. Single issues Publishing Company, Inc., 461 Eighth cost $3.50; back issues cost $4.50. Avenue, New York, NY 10001, U.S.A., in March, June, September, and Decem- Advertising rates can be had on request ber. Copyright © 1981 by Pella Publish- by writing to the Managing Editor. ing Company. Articles appearing in this Journal are The editors welcome the freelance sub- abstracted and/or indexed in Historical mission of articles, essays and book re- Abstracts and America: History and views. All submitted material should be Life; or in Sociological Abstracts; or in typewritten and double-spaced. Trans- Psychological Abstracts; or in the Mod- lations should be accompanied by the ern Language Association Abstracts (in- original text. Book reviews should be cludes International Bibliography) or in approximately 600 to 1,200 words in International Political Science Abstracts length. Manuscripts will not be re- in accordance with the relevance of con- turned unless they are accompanied by tent to the abstracting agency. a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All articles and reviews published in Subscription rates: Individual—$12.00 the Journal represent only the opinions for one year, $22.00 for two years; of the individual authors; they do not Foreign—$15.00 for one year by surface necessarily reflect the views of the mail; Foreign—$20.00 for one year by editors or the publisher NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALEXIS P. -

Modern Greece: a History Since 1821 John S

MODERN GREECE A History since 1821 JOHN S. KOLIOPOULOS AND THANOS M. VEREMIS A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405186810_1_Pretoc.indd iii 9/8/2009 10:48:21 PM 9781405186810_6_Index.indd 268 9/8/2009 10:58:29 PM MODERN GREECE 9781405186810_1_Pretoc.indd i 9/8/2009 10:48:21 PM A NEW HISTORY OF MODERN EUROPE This series provides stimulating, interpretive histories of particular nations of modern Europe. Assuming no prior knowledge, authors describe the development of a country through its emergence as a mod- ern state up to the present day. They also introduce readers to the latest historical scholarship, encouraging critical engagement with compara- tive questions about the nature of nationhood in the modern era. Looking beyond the immediate political boundaries of a given country, authors examine the interplay between the local, national, and international, set- ting the story of each nation within the context of the wider world. Published Modern Greece: A History since 1821 John S. Koliopoulos & Thanos M. Veremis Forthcoming Modern France Edward Berenson Modern Spain Pamela Radcliff Modern Ukraine Yaroslav Hrytsak & Mark Von Hagen Modern Hungary Mark Pittaway Modern Poland Brian Porter-Szucs Czechoslovakia Benjamin Frommer Yugoslavia Melissa Bokovoy & Sarah Kent 9781405186810_1_Pretoc.indd ii 9/8/2009 10:48:21 PM MODERN GREECE A History since 1821 JOHN S. KOLIOPOULOS AND THANOS M. VEREMIS A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405186810_1_Pretoc.indd iii 9/8/2009 10:48:21 PM This edition first published 2010 Copyright © 2010 John S. Koliopoulos and Thanos M. Veremis Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. -

Turning Ιnside Οut European University Heritage: Collections, Audiences, Stakeholders

Turning Ιnside Οut European University Heritage: Collections, Audiences, Stakeholders EDITORS: Marlen Mouliou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Greece) Sébastien Soubiran, University of Strasbourg (France) Soia Talas, University of Padua (Italy) Roland Wittje, Indian Institute of Technology Madras (India) EDITORS: Marlen Mouliou, Sébastien Soubiran, Soia Talas, Roland Wittje Title: Turning Ιnside Οut European University Heritage: Collections, Audiences, Stakeholders Graphic editing: Eleni Pastra, Printing Unit by the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Printed by the Printing Unit of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Language editing: Vineeta Rai Support editing: Myrsini Pichou Cover image: A young visitor during an audio-guide tour in the Athens University History Museum (Photo archive: Marlen Mouliou) © Copyright 2018, First Edition, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Press and contributors No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and the author. ΙSBN: 978-960-466-186-2 Turning Ιnside Οut European University Heritage: Collections, Audiences, Stakeholders PROCEEDINGS OF THE 16TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE UNIVERSEUM EUROPEAN ACADEMIC HERITAGE NETWORK NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS, 11 – 13 JUNE 2015, GREECE Programme Committee UNIVERSEUM 2015 ATHANASIOS KATERINOPOULOS, Professor Emeritus -

Macedonian Studies Journal 75 the Museum for the Macedonian Struggle Is Located in the Centre of the City of Thessaloniki, Centr

Macedonian Studies Journal The Museum for the Macedonian Struggle is located in the centre of the city of Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia, Greece. It occupies a neoclassical building built in 1893 and designed by the renowned German philhellene architect Ernst Ziller to house the Greek Consulate General in Thessaloniki. In its six ground-floor rooms the Museum graphically illustrates modern and contemporary history of Greek Macedonia. It presents the social, economic, political and military developments that shaped the fate of this historical Hellenic region between mid- nineteenth and early twentieth century. Through its exhibit the Museum enables the visitor to form a global picture not only of the revolutionary movements in the area but also of the rapidly changing society of the southern Balkans and its endeavour to balance between tradition and modernization. The Museum for the Macedonian Struggle and the Research Centre for Macedonian History and Documentation (KEMIT) are run by a special institution, the homonymous Foundation. The history of the building The building which today houses the Museum for the Macedonian Struggle was from 1894 to 1912 Greece’s Consulate-General at Salonica. It was erected on ground be- longing to the Salonica Inspectorate of Greek Teaching Establishments, right next to the Bishop’s Palace, after the great fire of August 23, 1890, which had destroyed the south- eastern quarters of Thessaloniki. Among the losses was the humble residence that till then housed the Consulate General of Greece, which was the property of the Greek Orthodox Community of Thessaloniki. With the insurance money, the donation of the bene- factor Andreas Syngros and the financial help offered by the Hel- lenic government, a sufficient amount was collected to recon- struct the buildings of the Greek community. -

Greco-Turkish Railway Connection: Illusions and Bargains in the Late Nineteenth Century Balkans*

BASIL C. G O U N A RI S GRECO-TURKISH RAILWAY CONNECTION: ILLUSIONS AND BARGAINS IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY BALKANS* In the minds of nineteenth century statesmen the ability of railways to stimulate finances assumed legendary proportions. Proponents connected railways with the immediate solution of considerable political and economic problems. The rapid progress that some European states experienced after constructing a railway network was pointing to the same direction. Naturally, such a prospect could not leave indifferent any state, especially those which were desperately trying to solve the problem of a growing budget deficit. Greece and the Ottoman Empire were no exception to the rule. Despite pro found financial weakness and a rather unfavourable political background they both tried to meet the railway challenge in a desperate attempt to catch up with modernisation. This paper, will first try to evaluate briefly the eco nomic and political prospects of railway building both in Greece and in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-nineteenth century. Then it will focus on the diplomatic manoeuvres of successive Greek governments, from the 1870s to the first decade of this century, to achieve Ottoman consent for a railway junction between the two neighbouring states. Finally it will examine the causes of failure to achieve this consent in an overall attempt to prove that the junction issue had never had a chance of success within the particular financial and political context. Railway planning in Greece was put forward as early as 1835, but the actual construction remained an unfulfilled dream for more than 35 years. -

Sakiz Adasi Ticareti

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ AKDENİZ DÜNYASI ARAŞTIRMALARI BİLİM DALI Yüksek Lisans Tezi XIX. YÜZYILDA SAKIZ ADASI TİCARETİ Hazırlayan: Hakan Başaralı 2501090345 Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Ali Fuat Örenç İstanbul 2012 XIX. Yüzyılda Sakız Adası Ticareti Hakan Başaralı ÖZ Sakız Adası, Cenevizlilerin hakimiyeti altında bulunduğu dönemde olduğu gibi Osmanlı idaresi zamanında da Avrupa, Doğu Akdeniz ve Kuzey Afrika arasındaki hatta seyahat eden ticaret gemilerinin mola verdikleri, seyahat durumuyla ilgili haber edindikleri önemli bir ticaret merkezi konumundaydı. Birçok akademik çalışmada önce XVI. Yüzyıl’da Sakız’ın Osmanlı tarafından fethedilmesiyle adadaki yabancı konsolosların İzmir’e taşınması ve sonra XIX. Yüzyılın başında adada vuku bulan 1821 Rum İsyanı gibi önemli hadiseler neticesinde Sakız Adası’nın ticari bakımdan İzmir’in gölgesinde kaldığı iddia edilerek adanın gerek Osmanlı Devleti gerekse Doğu Akdeniz coğrafyası içerisindeki durumu ihmal edilmiştir. Bu yüzden XIX. Yüzyıl’da Sakız ve Sakızlılar’ın ekonomik ve ticarî durumuna yeterince dikkat çekilmediğinden ada hakkında eksik değerlendirmelerle karşılaşılmaktadır. Bu eksikliğin giderilmesi yolunda mevcut çalışmada özellikle yabancı seyahatnameler, konsolos raporları, arşiv belgelerinden istifade edilerek Sakız Adası’nın XIX. yüzyıldaki ekonomik, ticarî konumu; yüzyıl sonunda inşa edilmiş olan yeni Sakız Limanı’nın oynadığı rol ele alınmıştır. Bunun dışında, 1822 Sakız İsyanı sonrasında adadan muhtelif ülkelere göç etmiş ada ahalisi tüccarlarının gittikleri yerlerde teşkil etmiş oldukları güçlü ticaret, finans ağı ve hâlâ Osmanlı İmparatorluğu topraklarında yaşayan akraba ve hemşehrileriyle olan ekonomik ilişkileri hakkında da ayrıntılı bilgi verilmeye çalışılmıştır. 2 ABSTRACT The island of Chios had occupied a significant position as a commercial center by being a port of call and a source of obtaining information for the merchantships that sail along Europe, Eastern Mediterranean and Northern Africa during the Otoman dominion likewise the precedent rule of Geneose.