Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{TEXTBOOK} Missing in Action

MISSING IN ACTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Francis Bergèse | 48 pages | 09 Feb 2017 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849183437 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Missing in Action () - IMDb Normalization of U. Considerable speculation and investigation has gone to a theory that a significant number of these men were captured as prisoners of war by Communist forces in the two countries and kept as live prisoners after the war's conclusion for the United States in Its unanimous conclusion found "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia. This missing in action issue has been a highly emotional one to those involved, and is often considered the last depressing, divisive aftereffect of the Vietnam War. To skeptics, "live prisoners" is a conspiracy theory unsupported by motivation or evidence, and the foundation for a cottage industry of charlatans who have preyed upon the hopes of the families of the missing. As two skeptics wrote in , "The conspiracy myth surrounding the Americans who remained missing after Operation Homecoming in had evolved to baroque intricacy. By , there were thousands of zealots—who believed with cultlike fervor that hundreds of American POWs had been deliberately and callously abandoned in Indochina after the war, that there was a vast conspiracy within the armed forces and the executive branch—spanning five administrations—to cover up all evidence of this betrayal, and that the governments of Communist Vietnam and Laos continued to hold an unspecified number of living American POWs, despite their adamant denials of this charge. It is only hard evidence of a national disgrace: American prisoners were left behind at the end of the Vietnam War. -

REFLECTION of PEACE Lined by Blocks of Granite That Hold the Names of Doves of Peace Reach to the Sky on Top of the Emerald the Deceased

OSSUARY The Ossuary at Roselawn has a spiraling pathway REFLECTION OF PEACE lined by blocks of granite that hold the names of Doves of peace reach to the sky on top of the emerald the deceased. The ashes are placed in a co-mingle green granite circular columbarium. Surrounded by container. beautiful gardens and benches. Ossuary In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains $895 Reflection of Peace* Co-Mingle Cremation Burial $3,800 Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription COMMUNITY Includes Placement and Inscription MAUSOLEUM Niche for 2 Cremains Reflection of Peace* Beautifully constructed bronze niche wall depicting $3,600 - $4,200 a Northern Minnesota Lake. This sculpture is said to Includes Placement and Inscription be the Largest Bronze Niche Wall in the World. See the front cover picture to view the entire mausoleum. Bronze Cremation Niche for 2 Cremains Roselawn Community Mausoleum* GARDEN OF $6,400 - $6,800 Includes Placement and Inscription REMEMBRANCE Price depends on row chosen Set into an embankment and accented with flowering topiary planters. It is a true work of beauty. And will SPLIT ROCK GARDEN forever be a peaceful resting place. Located near the Historic Roselawn Chapel, this In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains limestone wall is the backdrop for the newest cremation columbarium. Serene pond, gardens and sculpture Garden of Remembrance* add to the peaceful resting place. $4,600 Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription In Ground Burial Lots for 2 Cremains Split Rock Garden* $3,800 Wall Niche for 2 Cremains Includes Interment, Marker and Inscription Garden of Remembrance* HISTORICAL CHAPEL $4,400 - $5,000 Niche for 2 Cremains Split Rock Garden* Our historic chapel, designed by renowned architect Includes Placement and Inscription $3,800 - $4,400 Cass Gilbert, may be reserved by lot owners for Price depends on row chosen Includes Placement and Inscription funerals and memorial services. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

Heritage Ethics and Human Rights of the Dead

genealogy Article Heritage Ethics and Human Rights of the Dead Kelsey Perreault ID The Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art, and Culture, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 May 2018; Accepted: 13 July 2018; Published: 17 July 2018 Abstract: Thomas Laqueur argues that the work of the dead is carried out through the living and through those who remember, honour, and mourn. Further, he maintains that the brutal or careless disposal of the corpse “is an attack of extreme violence”. To treat the dead body as if it does not matter or as if it were ordinary organic matter would be to deny its humanity. From Laqueur’s point of view, it is inferred that the dead are believed to have rights and dignities that are upheld through the rituals, practices, and beliefs of the living. The dead have always held a place in the space of the living, whether that space has been material and visible, or intangible and out of sight. This paper considers ossuaries as a key site for investigating the relationships between the living and dead. Holding the bones of hundreds or even thousands of bodies, ossuaries represent an important tradition in the cultural history of the dead. Ossuaries are culturally constituted and have taken many forms across the globe, although this research focuses predominantly on Western European ossuary practices and North American Indigenous ossuaries. This paper will examine two case studies, the Sedlec Ossuary (Kutna Hora, Czech Republic) and Taber Hill Ossuary (Toronto, ON, Canada), to think through the rights of the dead at heritage sites. -

100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments

HOW TO ORDER 100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments Rome Monument offers you unlimited possibilities for your eternal resting place by completely personalizing a cemetery monument just for you…and just the way you want! Imagine capturing your life’s interests and passions in granite, making your custom monument far more meaningful to your family and for future generations. Since 1934, Rome Monument has showcased old world skills and stoneworking artistry to create totally unique, custom headstones and monuments. And because we cut out the middleman by making the monuments in our own facility, your cost may be even less than what other monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes charge. Visit a cemetery and you’ll immediately notice that many monuments and headstones look surprisingly alike. That’s because they are! Most monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes sell you stock monuments out of a catalog. You can mix and match certain design elements, but you can’t really create a truly personalized monument. Now you can create a monument you love and that’s as unique as the individual being memorialized. It starts with a call to Rome Monument. ROME MONUMENT • www.RomeMonuments.com • 724-770-0100 Rome Monument Main Showroom & Office • 300 West Park St., Rochester, PA WHAT’S PASSION What is truly unique and specialYour about you or a loved one? What are your interests? Hobbies? Passions? Envision how you want future generations of your family to know you and let us capture the essence of you in an everlasting memorial. Your Fai Your Hobby Spor Music Gardening Career Anima Outdoors Law Enforcement Military Heritage True Love ADDITIONAL TOPICS • Family • Ethnicity • Hunting & Fishing • Transportation • Hearts • Wedding • Flowers • Angels • Logos/Symbols • Emblems We don’t usee stock monument Personalization templates and old design catalogs to create your marker, monument, Process or mausoleum. -

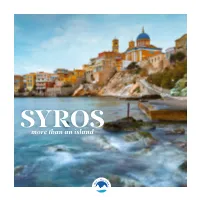

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Heartland of German History

Travel DesTinaTion saxony-anhalT HEARTLAND OF GERMAN HISTORY The sky paThs MAGICAL MOMENTS OF THE MILLENNIA UNESCo WORLD HERITAGE AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu 6 good reasons to visit Saxony-Anhalt! for fans of Romanesque art and Romance for treasure hunters naumburg Cathedral The nebra sky Disk for lateral thinkers for strollers luther sites in lutherstadt Wittenberg Garden kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz for knights of the pedal for lovers of fresh air elbe Cycle route Bode Gorge in the harz mountains The Luisium park in www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu the Garden Kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz Heartland of German History 1 contents Saxony-Anhalt concise 6 Fascination Middle Ages: “Romanesque Road” The Nabra Original venues of medieval life Sky Disk 31 A romantic journey with the Harz 7 Pomp and Myth narrow-gauge railway is a must for everyone. Showpieces of the Romanesque Road 10 “Mona Lisa” of Saxony-Anhalt walks “Sky Path” INForMaTive Saxony-Anhalt’s contribution to the history of innovation of mankind holiday destination saxony- anhalt. Find out what’s on 14 Treasures of garden art offer here. On the way to paradise - Garden Dreams Saxony-Anhalt Of course, these aren’t the only interesting towns and destinations in Saxony-Anhalt! It’s worth taking a look 18 Baroque music is Central German at www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu. 8 800 years of music history is worth lending an ear to We would be happy to help you with any questions or requests regarding Until the discovery of planning your trip. Just call, fax or the Nebra Sky Disk in 22 On the road in the land of Luther send an e-mail and we will be ready to the south of Saxony- provide any assistance you need. -

The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ IOANNA PEPELASIS MINOGLOU Athens University of Economics ABSTRACT This paper analyses the organizational makeup and financial techniques of Greek Diaspora banking during its golden era in Constantinople, circa 1840-1881. It is argued that this small group of bankers had a flexible style of business organization which included informal operations. Well embedded into the network of international high finance, these bankers facilitated the integration of Constantinople into the Western European capital markets -during the early days of Western financial presence in the Ottoman Empire- by developing an ingenious for the standards of the time and place method for the internationalization of the financial instruments of the Internal Ottoman Public Debt. 1 ‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ 1 Greek Diaspora bankers are among the lesser known ethnic minority groups in the history of international finance. Tight knit but cosmopolitan, Greek Diaspora banking sprang within the international mercantile community of Diaspora Greeks which was based outside Greece and specialized in the long distance trade in staples. By the first half of the nineteenth century it operated an advanced network of financial transactions spreading from Odessa, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria in the East to Leghorn, Marseilles, Paris, and London in the West.2 More specifically, circa 1840-1881, in Constantinople, Greek Diaspora bankers3 attained an elite status within the local community through their specialization in the financing of the Ottoman Public Debt. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

I Ana Rafaela Ferraz Ferreira Body Disposal in Portugal: Current

Ana Rafaela Ferraz Ferreira Body disposal in Portugal: Current practices and potential adoption of alkaline hydrolysis and natural burial as sustainable alternatives Dissertação de Candidatura ao grau de Mestre em Medicina Legal submetida ao Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar da Universidade do Porto. Orientador: Prof. Doutor Francisco Queiroz Categoria: Coordenador Adjunto do Grupo de Investigação “Heritage, Culture and Tourism” Afiliação: CEPESE – Centro de Estudos da População, Economia e Sociedade da Universidade do Porto i This page intentionally left blank. ii “We are eternal! But we will not last!” in Welcome To Night Vale iii This page intentionally left blank. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest thank you to my supervisor, Francisco Queiroz, who went above and beyond to answer my questions (and to ask new ones). This work would have been poorer and uglier and a lot less composed if you hadn’t been here to help me direct it. Thank you. My humblest thank you to my mother, father, and sister, for their unending support and resilience in enduring an entire year of Death-Related Fun Facts (and perhaps a month of grumpiness as the deadline grew closer and greater and fiercer in the horizon). We’ve pulled through. Thank you. My clumsiest thank you to my people (aka friends), for that same aforementioned resilience, but also for the constant willingness to bear ideological arms and share my anger at the little things gone wrong. I don’t know what I would have done without the 24/7 online support group that is our friendship. Thank you. Last, but not least, my endless thank you to Professor Fernando Pedro Figueiredo and Professor Maria José Pinto da Costa, for their attention to detail during the incredible learning moment that was my thesis examination. -

On the Trail of Bartholdi Press Kit

ON THE TRAIL OF BARTHOLDI PRESS KIT Press contact [email protected] www.tourisme-colmar.com Content Bartholdi Bartholdi 1 Masterpieces 4 The Bartholdi museum in Colmar 6 Colmarien creations 7 Les grands soutiens du Monde 7 Martin Schongauer fountain 7 Schwendi fountain 8 Bruat fountain 8 Roesselmann fountain 9 Statue of Général Rapp 9 Hirn monument 10 Bust of Jean-Daniel Hanbart 10 Le petit vigneron (The little winegrower) 11 Le tonnelier (The barrel-maker) 11 Le génie funèbre (The grave ghost) 12 Medallion at the tomb of Georges Kern 12 The grave of Voulminot 12 City map 13 Bartholdi Colmar, 2nd August 1834 – Paris, 4th October 1904 Frédérique Auguste Bartholdi, son of Jean-Charles Bartholdi counsellor of the prefecture and Augusta-Charlotte, daughter of a mayor of Ribeauvillé, is the most celebrated artist in Alsace. Until the premature death of his father, Bartholdy is two years old, he lives in the Rue des Marchands, 30 in Colmar. His wealthy mother decides to live from now in Paris while keeping the house in Colmar which is used as Bartholdi museum since 1922. From 1843 to 1851 Bartholdi goes to Louis-Le-Grand school and takes art lessons of painting with Ary Scheffer. He continues his studies at the art academie (École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts), profession architecture, and takes underwriting lessons with M. Rossbach in Colmar, where his family spends holiday. In 1852 Barholdi opens his first studio in Paris. At the age of 19, in 1853, he gets the first order coming from his birth town – they ask him to build a statue of the General Rapp.