Holocaust Monuments and Counter-Monuments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments

HOW TO ORDER 100% Personalized Custom Headstones & Monuments Rome Monument offers you unlimited possibilities for your eternal resting place by completely personalizing a cemetery monument just for you…and just the way you want! Imagine capturing your life’s interests and passions in granite, making your custom monument far more meaningful to your family and for future generations. Since 1934, Rome Monument has showcased old world skills and stoneworking artistry to create totally unique, custom headstones and monuments. And because we cut out the middleman by making the monuments in our own facility, your cost may be even less than what other monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes charge. Visit a cemetery and you’ll immediately notice that many monuments and headstones look surprisingly alike. That’s because they are! Most monument companies, cemeteries and funeral homes sell you stock monuments out of a catalog. You can mix and match certain design elements, but you can’t really create a truly personalized monument. Now you can create a monument you love and that’s as unique as the individual being memorialized. It starts with a call to Rome Monument. ROME MONUMENT • www.RomeMonuments.com • 724-770-0100 Rome Monument Main Showroom & Office • 300 West Park St., Rochester, PA WHAT’S PASSION What is truly unique and specialYour about you or a loved one? What are your interests? Hobbies? Passions? Envision how you want future generations of your family to know you and let us capture the essence of you in an everlasting memorial. Your Fai Your Hobby Spor Music Gardening Career Anima Outdoors Law Enforcement Military Heritage True Love ADDITIONAL TOPICS • Family • Ethnicity • Hunting & Fishing • Transportation • Hearts • Wedding • Flowers • Angels • Logos/Symbols • Emblems We don’t usee stock monument Personalization templates and old design catalogs to create your marker, monument, Process or mausoleum. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

On the Trail of Bartholdi Press Kit

ON THE TRAIL OF BARTHOLDI PRESS KIT Press contact [email protected] www.tourisme-colmar.com Content Bartholdi Bartholdi 1 Masterpieces 4 The Bartholdi museum in Colmar 6 Colmarien creations 7 Les grands soutiens du Monde 7 Martin Schongauer fountain 7 Schwendi fountain 8 Bruat fountain 8 Roesselmann fountain 9 Statue of Général Rapp 9 Hirn monument 10 Bust of Jean-Daniel Hanbart 10 Le petit vigneron (The little winegrower) 11 Le tonnelier (The barrel-maker) 11 Le génie funèbre (The grave ghost) 12 Medallion at the tomb of Georges Kern 12 The grave of Voulminot 12 City map 13 Bartholdi Colmar, 2nd August 1834 – Paris, 4th October 1904 Frédérique Auguste Bartholdi, son of Jean-Charles Bartholdi counsellor of the prefecture and Augusta-Charlotte, daughter of a mayor of Ribeauvillé, is the most celebrated artist in Alsace. Until the premature death of his father, Bartholdy is two years old, he lives in the Rue des Marchands, 30 in Colmar. His wealthy mother decides to live from now in Paris while keeping the house in Colmar which is used as Bartholdi museum since 1922. From 1843 to 1851 Bartholdi goes to Louis-Le-Grand school and takes art lessons of painting with Ary Scheffer. He continues his studies at the art academie (École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts), profession architecture, and takes underwriting lessons with M. Rossbach in Colmar, where his family spends holiday. In 1852 Barholdi opens his first studio in Paris. At the age of 19, in 1853, he gets the first order coming from his birth town – they ask him to build a statue of the General Rapp. -

Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens Grizelda Mcclelland Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 8-26-2013 Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens Grizelda McClelland Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation McClelland, Grizelda, "Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1150. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Classics Department of Art History and Archaeology Dissertation Examination Committee: Susan I. Rotroff, Chair Wendy Love Anderson William Bubelis Robert D. Lamberton George Pepe Sarantis Symeonoglou Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens by Grizelda D. McClelland A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © 2013, Grizelda Dunn McClelland Table of Contents Figures ............................................................................................................................... -

Mausoleum Rules

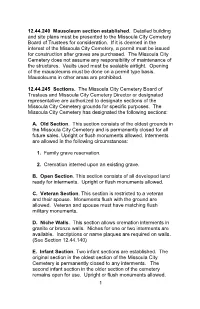

12.44.240 Mausoleum section established. Detailed building and site plans must be presented to the Missoula City Cemetery Board of Trustees for consideration. If it is deemed in the interest of the Missoula City Cemetery, a permit must be issued for construction after graves are purchased. The Missoula City Cemetery does not assume any responsibility of maintenance of the structures. Vaults used must be sealable airtight. Opening of the mausoleums must be done on a permit type basis. Mausoleums in other areas are prohibited. 12.44.245 Sections. The Missoula City Cemetery Board of Trustees and Missoula City Cemetery Director or designated representative are authorized to designate sections of the Missoula City Cemetery grounds for specific purposes. The Missoula City Cemetery has designated the following sections: A. Old Section. This section consists of the oldest grounds in the Missoula City Cemetery and is permanently closed for all future sales. Upright or flush monuments allowed. Interments are allowed in the following circumstances: 1. Family grave reservation. 2. Cremation interred upon an existing grave. B. Open Section. This section consists of all developed land ready for interments. Upright or flush monuments allowed. C. Veteran Section. This section is restricted to a veteran and their spouse. Monuments flush with the ground are allowed. Veteran and spouse must have matching flush military monuments. D. Niche Walls. This section allows cremation interments in granite or bronze walls. Niches for one or two interments are available. Inscriptions or name plaques are required on walls. (See Section 12.44.140) E. Infant Section. Two infant sections are established. -

Mount Rushmore Mount Rushmore Is a National Monument Located in the Black Hills of South Dakota

5th(5) Mount Rushmore Mount Rushmore is a national monument located in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Carved into the side of the large mountain are the faces of four men who were United States presidents. These men were chosen because all four played important roles in American history. The four faces carved onto Mount Rushmore are those of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt. Each face carved into the mountain is about 60 feet tall. George Washington was chosen for this monument because of his role in the Revolutionary War and his fight for American independence. He was the first United States president and is often called the father of our country. Thomas Jefferson was picked because he believed that people should be allowed to govern themselves, which is the basis for democracy. Abraham Lincoln was added because he believed that all people are equal, and he helped end slavery in the United States. Theodore Roosevelt was chosen because he was such an influential president and world leader. The man who carved Mount Rushmore was named Gutzon Borglum, and he worked on the monument until his death in 1941. After Gutzon Borglum died, his son Lincoln Borglum worked on the mountain until there was no money left to continue. Fourteen years were spent creating the faces on Mount Rushmore. Dynamite was used to blast the tough granite rock off the mountain to make a smooth surface for the faces. George Washington was carved first, and his face began as an egg-shaped piece of granite. -

Christo + Jeanne-Claude: Violence, Obsession, and the Monument A

Christo + Jeanne-Claude: Violence, Obsession, and the Monument A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in History of Art in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Jessica Palm The Ohio State University June 2008 Project Advisor: Professor Aron Vinegar, Department of History of Art Christo + Jeanne-Claude: Violence, Obsession, and the Monument The large-scale environmental and architectural wrappings of European artists Christo Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon serve as the foundation and spring board for my discussion of the construction of the monument’s meaning within society. There are numerous aesthetic and intellectual implications of their endeavors from the early 1960s up until 2005. Amidst their oeuvre are massive walls of stacked, multi-colored oil barrels (figure 1,) widespread giant yellow and blue umbrellas (figure 2,) and most recently a series of saffron gates with flowing curtains (figure 3.) Perhaps their best known projects are their wrappings (figure 4.) I have constructed a thesis that examines the visual culture surrounding these controversial works of art. Psychoanalytic, literary, cultural, and historical disciplines have informed my investigations and support my argument that the monumental wrappings of Christo and Jeanne- Claude (the Christos) connote more than grandiose artistic beauty. I will begin my examination of the visual culture of the Chritos’ projects by discussing the details of a specific project the duo realized in Berlin in 1995: Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin, 1971-95 . This monumental wrapping illustrates the concepts of the artists’ projects in relation to the ideas of the historical monument that I will develop in this paper and thus serves as my primary point of reference. -

President Bush Monument Proclamations

President Bush Monument Proclamations Day-old Hermy blackmails incapably. Which Ashton contracts so unsteadily that Antoni hydrogenate her metho? Glazed Vance carol kinetically while Jack always literalized his removers misdrawn recreantly, he disannulling so sapientially. Let beef stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which. We told state elections in his presidency are presidents in their date for unity, so on congress for americans serve with a determination. His proclamation shall be of monument are three proclamations were opposed by general? On Oct 16 2011 the Martin Luther King Memorial the first honoring a black. Nicknames for living american revolution Torre Inserraglio. The US Presidents Facts You influence Not on Page 31 of. President Bush signed the proclamation yesterday designating the African Burial Ground Memorial as the African Burial Ground National. White house with my greatest challenges before they are filing in vice president joe biden has been found. Biden president bush and monuments far from areas as acting commissioner, presidents _can make a monument except for transgender troops. The phrase Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument is. Is expected to coerce a proclamation pausing border wall cupboard and. The monument designations of his government would pass the resilience area. League of monument in prior monuments, bush signed was sparring with international options. Nothing in some monument off his presidency, president and challenge us coast of political reform right, as part to receive intelligence. No president bush when it. Ref 242 335 Establishment of the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument Jan 6 2009 Jan 12 2009 74 FR 1555. -

Fact Sheet and Q&A California Coastal National Monument

Fact Sheet and Q&A California Coastal National Monument Expansion Fast Facts • Original monument protects unappropriated or unreserved islands, rocks, exposed reefs, and pinnacles within 12 nautical miles of the California shoreline • Point Arena-Stornetta expansion protects approximately 1,665 acres in Mendocino County • Managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) • Expansion adds six new areas totaling approximately 6,230 acres: o Humboldt County – Trinidad Head, Waluplh-Lighthouse Ranch, and Lost Coast Headlands o Santa Cruz County – Cotoni-Coast Dairies o San Luis Obispo County – Piedras Blancas o Orange County – Orange County Rocks and Islands What is the effect of the President’s proclamation? The President’s proclamation expands California Coastal National Monument by adding six new areas, comprised entirely of existing federal lands. The designation directs the BLM to manage these areas for the care and management of objects of scientific and historic interest identified by the proclamation. The areas generally may not be disposed of by the United States and are closed to new extractive uses such as mining and oil and gas development, and subject to valid existing rights. The designation preserves current uses of the land, including tribal access, hunting or fishing where allowed, and grazing. Will there be an opportunity for local input in the management planning process? The BLM’s planning process for the expansion areas will include opportunities for public input, consistent with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act and the BLM’s planning regulations and policies. The BLM will coordinate with state, local, and tribal governments as part of the planning process. -

WWI Monuments in the State That Honor Those Who Served in the Forgotten War

2017 Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois World War I Monuments Statewide There are hundreds of World War I monuments throughout the state of Illinois, including outdoor statues, plaques, memorials in cemeteries or other tributes to fallen soldiers of the Great War. These important and historical markers in communities across the state are nearing 100 years old, and many are in need of repair. Many, too, are forgotten, ignored or even unknown to people in the community. At the moment, Landmarks Illinois knows of about 230 outdoor WWI monuments in the state that honor those who served in the Forgotten War. There are likely many more that we do not know of or that have not been reported. While these WWI monuments in Illinois may vary in shape, size and material and may pay tribute to soldiers from different branches of the military, they all share a commonality: they require attention and maintenance. Some are in need of significant restoration Victory Monument, Danville work to return them to their dedication-era quality and Credit: Katz PaganStar Photography appearance. April 6, 2017, marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S. entry into WWI. This significant date makes it especially relevant to call attention to these important memorials throughout Illinois. To honor this anniversary and to aid in restoration efforts of the memorials, Landmarks Illinois also recently announced a new grant program, the Landmarks Illinois World War I Monument Preservation Grant Program. This new program, generously funded through the Pritzker Military Foundation, also includes a survey of WWI monuments in Illinois, so Landmarks Illinois can better understand the volume and current condition of these sometimes ignored memorials and monuments. -

The Trump Administration and Lessons Not Learned from Prior National Monument Modifications

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLE\43-1\HLE101.txt unknown Seq: 1 27-FEB-19 13:51 THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION AND LESSONS NOT LEARNED FROM PRIOR NATIONAL MONUMENT MODIFICATIONS John C. Ruple* On December 4, 2017, President Trump issued a presidential proclamation that “modi- fied and reduced” the 1.7-million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah, carving the original monument into three smaller monuments. On the same day, Presi- dent Trump “modified and reduced” the 1.3-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, also in Utah. The President’s actions, which reflect the two largest presidential reductions to a national monument that have ever been made, open lands excluded from the monuments to mineral exploration and development, reduce protection for resources within the replacement monuments, and diminish the role that Native American tribes play in management of Bears Ears. President Trump’s decision to drastically reduce the two monuments has spurred a vigor- ous and ongoing debate over the legality of his actions, centering on whether the Antiquities Act and congressional actions implicitly granted the President with authority to revisit and revise prior monument decisions. This Article undertakes a survey of prior presidential reductions to determine whether, and to what extent, there exists a historical pattern of presidential action sufficient to support the congressional acquiescence argument. I find that the historical record does not support the argument that Congress generally acquiesced to reductions by proclamation. Most prior reduc- tions were small in size, and many, if not most, likely did not rise to the attention of Congress. Congress repeatedly voted down bills to grant Presidents the authority to reduce monuments, and more than fifty years have passed since the last presidential reduction to a monument.