Black Sea Project Working Papers Vol. V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second Group in the First Turkish Grand National Assembly I. Dönem

GAUN JSS The Second Group in the First Turkish Grand National Assembly I. Dönem Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi’nde İkinci Grup Gülay SARIÇOBAN* Abstract The First Turkish Grand National Assembly, called the First Parliament in the history of our Republic, is the most significant and important mission of our recent history. In fact, it is an extraordinary assembly that has achieved such a challenging task as the National Struggle with an endless effort. The ideas contained within each community reflect the pains they have experienced during the development process. Different ideas and methods gave the Parliament a colorful and dynamic structure. We can call the struggle between the First and Second Groups in the First Parliament as the pro-secular progressives and the reigners who defended the Otto- man order. The first group represented the power and the second group represented the opposition. Therefore, the First Group was the implementing side and the Second Group was a critic of these practices. The Second Group argued that in terms of their ideas, not just of their time, has also been the source of many political con- flicts in the Republic of Turkey. Thus, the Second Group has marked the next political developments. The Se- cond Group, which played such an important role, forced us to do such work. Our aim is to put forward the task undertaken by the Second Group until its dissolution. In this study, we try to evaluate the Second Group with the ideas it represents, its effectiveness within the Parliament and its contribution to the political developments. -

Lilo Linke a 'Spirit of Insubordination' Autobiography As Emancipatory

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ autobiography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/177/ Version: Full Version Citation: Ogurla, Anita Judith (2016) Lilo Linke a ’Spirit of insubordination’ auto- biography as emancipatory pedagogy : a Turkish case study. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Lilo Linke: A ‘Spirit of Insubordination’ Autobiography as Emancipatory Pedagogy; A Turkish Case Study Anita Judith Ogurlu Humanities & Cultural Studies Birkbeck College, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, February 2016 I hereby declare that the thesis is my own work. Anita Judith Ogurlu 16 February 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines the life and work of a little-known interwar period German writer Lilo Linke. Documenting individual and social evolution across three continents, her self-reflexive and autobiographical narratives are like conversations with readers in the hope of facilitating progressive change. With little tertiary education, as a self-fashioned practitioner prior to the emergence of cultural studies, Linke’s everyday experiences constitute ‘experiential learning’ (John Dewey). Rejecting her Nazi-leaning family, through ‘fortunate encounter[s]’ (Goethe) she became critical of Weimar and cultivated hope by imagining and working to become a better person, what Ernst Bloch called Vor-Schein. Linke’s ‘instinct of workmanship’, ‘parental bent’ and ‘idle curiosity’ was grounded in her inherent ‘spirit of insubordination’, terms borrowed from Thorstein Veblen. -

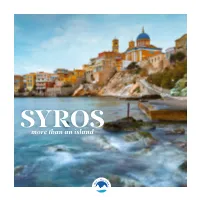

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

Trebizond and North-Eastern Turkey

TREBIZOND AND NORTH-EASTERN TURKEY BY DENIS A. H. WRIGHT A lecture delivered to the Royal Central Asian Society on Wednesday, October 24, 1945. In the Chair, Admiral Sir Howard Kelly, G.B.E., K.C.B., C.M.G., M.V.O. The CHAIRMAN, in introducing the lecturer, said: Mr. Denis Wright is going to speak to us about the port of Trebizond, whose poetical- sounding name suggests the starting-point of the " Golden Road to Samarkand." I had the pleasure of serving with Mr. Wright in Turkey. From September, 1939, to February, 1941, he was British Vice-Consul at Constanta. After the rupture of diplomatic relations with Rumania he went to take charge of the British Consulate at Trebizond. There, for almost two years, he and his wife were the only two English people; for part of that time he was the only British representative on the Black Sea. From May, 1943, until January of 1945 Mr. Wright was our Consul at Mersin. Although he and I had no direct dealings with each other, I know he was one of the most co-operative of all the British officials in Turkey, and that he did everything he possibly could to help the Services. WHEN in February, 1941, I passed through Ankara on my first visit to Trebizond I was told three things about the place: firstly, that it was the centre of a very large hazelnut-producing area, probably the largest in the world; secondly, that my British community there would be a very small one; and, thirdly, that Trebizond had for many hundreds of years been the transit port of a most important trade to and from Persia, that that trade still flourished, and that I should see camels arriving daily from Persia loaded with all the exotic merchandise of the East. -

Talaat Pasha's Report on the Armenian Genocide.Fm

Gomidas Institute Studies Series TALAAT PASHA’S REPORT ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Ara Sarafian Gomidas Institute London This work originally appeared as Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917. It has been revised with some changes, including a new title. Published by Taderon Press by arrangement with the Gomidas Institute. © 2011 Ara Sarafian. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-903656-66-2 Gomidas Institute 42 Blythe Rd. London W14 0HA United Kingdom Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction by Ara Sarafian 5 Map 18 TALAAT PASHA’S 1917 REPORT Opening Summary Page: Data and Calculations 20 WESTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 22 Constantinople 23 Edirne vilayet 24 Chatalja mutasarriflik 25 Izmit mutasarriflik 26 Hudavendigar (Bursa) vilayet 27 Karesi mutasarriflik 28 Kala-i Sultaniye (Chanakkale) mutasarriflik 29 Eskishehir vilayet 30 Aydin vilayet 31 Kutahya mutasarriflik 32 Afyon Karahisar mutasarriflik 33 Konia vilayet 34 Menteshe mutasarriflik 35 Teke (Antalya) mutasarriflik 36 CENTRAL PROVINCES (MAP) 37 Ankara (Angora) vilayet 38 Bolu mutasarriflik 39 Kastamonu vilayet 40 Janik (Samsun) mutasarriflik 41 Nigde mutasarriflik 42 Kayseri mutasarriflik 43 Adana vilayet 44 Ichil mutasarriflik 45 EASTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 46 Sivas vilayet 47 Erzerum vilayet 48 Bitlis vilayet 49 4 Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide Van vilayet 50 Trebizond vilayet 51 Mamuretulaziz (Elazig) vilayet 52 SOUTH EASTERN PROVINCES AND RESETTLEMENT ZONE (MAP) 53 Marash mutasarriflik 54 Aleppo (Halep) vilayet 55 Urfa mutasarriflik 56 Diyarbekir vilayet -

Mantar Dergisi

11 6845 - Volume: 20 Issue:1 JOURNAL - E ISSN:2147 - April 20 e TURKEY - KONYA - FUNGUS Research Center JOURNAL OF OF JOURNAL Selçuk Selçuk University Mushroom Application and Selçuk Üniversitesi Mantarcılık Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi KONYA-TÜRKİYE MANTAR DERGİSİ E-DERGİ/ e-ISSN:2147-6845 Nisan 2020 Cilt:11 Sayı:1 e-ISSN 2147-6845 Nisan 2020 / Cilt:11/ Sayı:1 April 2020 / Volume:11 / Issue:1 SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ MANTARCILIK UYGULAMA VE ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZİ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ ADINA SAHİBİ PROF.DR. GIYASETTİN KAŞIK YAZI İŞLERİ MÜDÜRÜ DR. ÖĞR. ÜYESİ SİNAN ALKAN Haberleşme/Correspondence S.Ü. Mantarcılık Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Müdürlüğü Alaaddin Keykubat Yerleşkesi, Fen Fakültesi B Blok, Zemin Kat-42079/Selçuklu-KONYA Tel:(+90)0 332 2233998/ Fax: (+90)0 332 241 24 99 Web: http://mantarcilik.selcuk.edu.tr http://dergipark.gov.tr/mantar E-Posta:[email protected] Yayın Tarihi/Publication Date 27/04/2020 i e-ISSN 2147-6845 Nisan 2020 / Cilt:11/ Sayı:1 / / April 2020 Volume:11 Issue:1 EDİTÖRLER KURULU / EDITORIAL BOARD Prof.Dr. Abdullah KAYA (Karamanoğlu Mehmetbey Üniv.-Karaman) Prof.Dr. Abdulnasır YILDIZ (Dicle Üniv.-Diyarbakır) Prof.Dr. Abdurrahman Usame TAMER (Celal Bayar Üniv.-Manisa) Prof.Dr. Ahmet ASAN (Trakya Üniv.-Edirne) Prof.Dr. Ali ARSLAN (Yüzüncü Yıl Üniv.-Van) Prof.Dr. Aysun PEKŞEN (19 Mayıs Üniv.-Samsun) Prof.Dr. A.Dilek AZAZ (Balıkesir Üniv.-Balıkesir) Prof.Dr. Ayşen ÖZDEMİR TÜRK (Anadolu Üniv.- Eskişehir) Prof.Dr. Beyza ENER (Uludağ Üniv.Bursa) Prof.Dr. Cvetomir M. DENCHEV (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaristan) Prof.Dr. Celaleddin ÖZTÜRK (Selçuk Üniv.-Konya) Prof.Dr. Ertuğrul SESLİ (Trabzon Üniv.-Trabzon) Prof.Dr. -

The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ IOANNA PEPELASIS MINOGLOU Athens University of Economics ABSTRACT This paper analyses the organizational makeup and financial techniques of Greek Diaspora banking during its golden era in Constantinople, circa 1840-1881. It is argued that this small group of bankers had a flexible style of business organization which included informal operations. Well embedded into the network of international high finance, these bankers facilitated the integration of Constantinople into the Western European capital markets -during the early days of Western financial presence in the Ottoman Empire- by developing an ingenious for the standards of the time and place method for the internationalization of the financial instruments of the Internal Ottoman Public Debt. 1 ‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ 1 Greek Diaspora bankers are among the lesser known ethnic minority groups in the history of international finance. Tight knit but cosmopolitan, Greek Diaspora banking sprang within the international mercantile community of Diaspora Greeks which was based outside Greece and specialized in the long distance trade in staples. By the first half of the nineteenth century it operated an advanced network of financial transactions spreading from Odessa, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria in the East to Leghorn, Marseilles, Paris, and London in the West.2 More specifically, circa 1840-1881, in Constantinople, Greek Diaspora bankers3 attained an elite status within the local community through their specialization in the financing of the Ottoman Public Debt. -

Divovich-Et-Al-Russia-Black-Sea.Pdf

Fisheries Centre The University of British Columbia Working Paper Series Working Paper #2015 - 84 Caviar and politics: A reconstruction of Russia’s marine fisheries in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov from 1950 to 2010 Esther Divovich, Boris Jovanović, Kyrstn Zylich, Sarah Harper, Dirk Zeller and Daniel Pauly Year: 2015 Email: [email protected] This working paper is available by the Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T made 1Z4, Canada. CAVIAR AND POLITICS: A RECONSTRUCTION OF RUSSIA’S MARINE FISHERIES IN THE BLACK SEA AND SEA OF AZOV FROM 1950 TO 2010 Esther Divovich, Boris Jovanović, Kyrstn Zylich, Sarah Harper, Dirk Zeller and Daniel Pauly Sea Around Us, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, Canada Corresponding author : [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of the present study was to reconstruct total Russian fisheries catch in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov for the period 1950 to 2010. Using catches presented by FAO on behalf of the USSR and Russian Federation as a baseline, total removals were estimated by adding estimates of unreported commercial catches, discards at sea, and unreported recreational and subsistence catches. Estimates for ‘ghost fishing’ were also made, but not included in the final reconstructed catch. Total removals by Russia were estimated to be 1.57 times the landings presented by FAO (taking into account USSR-disaggregation), with unreported commercial catches, discards, recreational, and subsistence fisheries representing an additional 30.6 %, 24.7 %, 1.0%, and 0.7 %, respectively. Discards reached their peak in the 1970s and 1980s during a period of intense bottom trawling for sprat that partially contributed to the large-scale fisheries collapse in the 1990s. -

Cıepo-22 Programme

Sosyal Faaliyet ve Geziler (Social Events and Excursions) Tuesday, 4 October 19.00- 21.00 Kokteyl (Coctail) Osman Turan Kültür ve Kongre Merkezi Saturday, 8 October 10.00- 16.00 Uzungöl Gezisi (Excursion to Uzungöl) Tuesday, 4 October 08.00- 10.00 Registration Prof. Dr. Osman Turan Kültür ve Kongre Merkezi 10.00- 10.40 Opening Hasan Turan Kongre Salonu Kenan İnan Michael Ursinus (The President of CIEPO) Hikmet Öksüz (Vice Rector of KTU) Orhan Fevzi Gümrükçüoğlu (Metropolitan Mayor of Trabzon) 10.40- 11.00 Coffee- Tea 11.00- 12.30 Morning Plenary Session Hasan Turan Kongre Salonu Chair Ilhan Şahin 11.00- 11.30 Mehmet Öz Halil İnalcık ve Osmanlı Sosyal- Ekonomi Tarihi Çalışmaları 11.30- 12.00 Ali Akyıldız İnsanı Yazmak: Osmanlı Biyografi Yazıcılığı ve Problemleri Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme 12.00- 12.15 Amy Singer Presentation of Digital Ottoman Platform 12.15- 12.30 Michael Ursinus CIEPO Article Prize Ceremony Laudatio introduced by the Chair of the Prize Selection Committee 12.30- 14.00 Lunch Tuesday, 4 October Afternoon Session Hasan Turan Kongre Salonu Panel- Klasik Dönem Osmanlı Trabzon’u Chair Kenan İnan 14.00-14.20 Kenan İnan 17. Asrın İkinci Yarısında Trabzon Yeniçeri Zabitleri 14.20-14.40 Turan Açık 17. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında Trabzon’da Muhtedi Yeniçeriler 14.40-15.00 Sebahittin Usta 17. Yüzyılın İkinci Yarısında Trabzon’da Para Vakıfları 15.00-15.20 Miraç Tosun Trabzon’da Misafir Olarak Bulunan Gayrimüslimlerin Terekeleri (1650-1800) 15.30-16.00 Coffee-Tea Chair Dariusz Kolodziejzyk 16.00-16.20 Kostantin Golev Crimean Littoral between -

Catalogue: May #2

CATALOGUE: MAY #2 MOSTLY OTTOMAN EMPIRE, THE BALKANS, ARMENIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST - Books, Maps & Atlases 19th & 20th Centuries www.pahor.de 1. COSTUMES OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A small, well made drawing represents six costumes of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The numeration in the lower part indicates, that the drawing was perhaps made to accompany a Anon. [Probably European artist]. text. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century] Pencil and watercolour on paper (9,5 x 16,5 cm / 3.7 x 6.5 inches), with edges mounted on 220 EUR later thick paper (28 x 37,5 cm / 11 x 14,8 inches) with a hand-drawn margins (very good, minor foxing and staining). 2. GREECE Anon. [Probably a British traveller]. A well made drawing represents a Greek house, indicated with a title as a house between the port city Piraeus and nearby Athens, with men in local costumes and a man and two young girls in House Between Piraeus and Athens. central or west European clothing. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century]. The drawing was perhaps made by one of the British travellers, who more frequently visited Black ink on thick paper, image: 17 x 28 cm (6.7 x 11 inches), sheet: 27 x 38,5 cm (10.6 x 15.2 Greece in the period after Britain helped the country with its independence. inches), (minor staining in margins, otherwise in a good condition). 160 EUR 3. OTTOMAN GEOLOGICAL MAP OF TURKEY: Historical Context: The Rise of Turkey out of the Ottoman Ashes Damat KENAN & Ahmet Malik SAYAR (1892 - 1965). -

The Gabriel Aubaret Archive of Ottoman Economic and Transportation History

www.pahor.de Tuesday, January 29th, 2019. THE GABRIEL AUBARET ARCHIVE OF OTTOMAN ECONOMIC AND TRANSPORTATION HISTORY Alexander Johnson, Ph.D. Including approximately 1,300 mostly unpublished primary sources: *The Secret Early Archives of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration. *The Archives of the project to link-up the Rumelian Railway, leading to the completion of the line for The Orient Express. *The Papers concerning the French-led bid for the Anatolian Railway (later the Baghdad Railway). *Important Archives concerning the Régie, the Ottoman Tobacco Monopoly. PRICE: EURO 55,000. 1 2 TABLE of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION / EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………….…….………………6 ‘Quick Overview’ of Archive Documents………………………………………………………………………..12 Gabriel Aubaret Biography……………………………………………………………………………...………..14 PART I: THE OTTOMAN PUBLIC DEBT ADMINISTRATION………………………………………….17 The Creation of the OPDA and its Early Operations…………………………………………………………..…19 THE OPDA ARCHIVES IN FOCUS………………………………………………………………………..…26 A. Foundational Documents……………………………………………………………………….……..27 B. The Secret OPDA Minutes, or Procès-Verbaux………………………………………………………42 C. Operational Documents…………………………………………………………..……………………51 D. Collection of Telegrams and Drafts…………………………………………………………….……101 PART II. OTTOMAN RAILWAYS…………………………………………………………………………..102 A. THE RUMELIAN RAILWAY: COMPLETING THE ORIENT EXPRESS……………………………………………………….…104 THE RUMELIAN RAILWAY ARCHIVE IN FOCUS………………………………………………………...109 1. The Procès-verbaux (Minutes) of the Conseil d’Administration…………………………….………109 2. Original -

Additions to the Turkish Aphid Fauna (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea: Aphididae)

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 7 (2): 318-321 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2011 Article No.: 111206 www.herp-or.uv.ro/nwjz Additions to the Turkish Aphid fauna (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea: Aphididae) Gazi GÖRÜR*, İlker TEPECİK, Hayal AKYILDIRIM and Gülay OLCABEY Nigde University, Department of Biology, 51100 Nigde-Turkey. *Corresponding author, G. Görür’s e-mail: [email protected] Received: 12. July 2010 / Accepted: 10. April 2011 / Available online: 30.April 2011 Abstract. As a result of the study carried out between 2007 and 2009 in far Eastern part of the Black Sea Re- gion of Turkey to determine aphid species on herbaceous plants, 17 species were determined as new records for Turkey aphid fauna. New recorded species are Aphis acanthoidis (Börner 1940), Aphis brunellae Schouteden 1903, Aphis genistae Scopoli 1763, Aphis longituba Hille Ris Lambers 1966, Aphis molluginis (Börner 1950), Aphis pseudocomosa Stroyan 1972, Aphis thomasi (Börner 1950), Capitophorus inulae (Passerini 1860), Metopolophium tenerum Hille Ris Lambers 1947, Microlophium sibiricum (Mordvilko 1914), Sitobion miscanthi (Takahashi 1921), Uroleucon ambrosiae (Thomas 1878), Uroleucon compositae (Theobald 1915), Uroleucon kikioense (Shinji 1941), Uroleucon pulicariae (Hille Ris Lambers 1933), Uroleucon scorzonerae Danielsson 1973, Uroleucon siculum Barba- gallo & Stroyan 1980. With these new records, the number of the species increased to 472 in Turkey aphid fauna. Key words: Aphid, Aphidoidea, herbaceous plants, Turkey. The known world aphid fauna consists of about (2008), Eser et al. (2009), Görür et al. (2009), 4500 species and 250 of those species are thought Akyürek et al. (2010) and Barjadze et al. (2011) to be serious pests around the world, and also in added 36 new records and the total number of the Turkey, where they cause economically important aphid species increased to 455.