Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

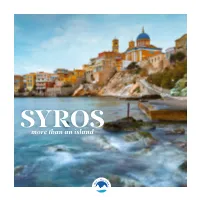

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ IOANNA PEPELASIS MINOGLOU Athens University of Economics ABSTRACT This paper analyses the organizational makeup and financial techniques of Greek Diaspora banking during its golden era in Constantinople, circa 1840-1881. It is argued that this small group of bankers had a flexible style of business organization which included informal operations. Well embedded into the network of international high finance, these bankers facilitated the integration of Constantinople into the Western European capital markets -during the early days of Western financial presence in the Ottoman Empire- by developing an ingenious for the standards of the time and place method for the internationalization of the financial instruments of the Internal Ottoman Public Debt. 1 ‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ 1 Greek Diaspora bankers are among the lesser known ethnic minority groups in the history of international finance. Tight knit but cosmopolitan, Greek Diaspora banking sprang within the international mercantile community of Diaspora Greeks which was based outside Greece and specialized in the long distance trade in staples. By the first half of the nineteenth century it operated an advanced network of financial transactions spreading from Odessa, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria in the East to Leghorn, Marseilles, Paris, and London in the West.2 More specifically, circa 1840-1881, in Constantinople, Greek Diaspora bankers3 attained an elite status within the local community through their specialization in the financing of the Ottoman Public Debt. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

Civil Affairs Handbook on Greece

Preliminary Draft CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK on GREECE feQfiJtion Thirteen on fcSSLJC HJI4LTH 4ND S 4 N 1 T £ T I 0 N THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE PROVOST MARSHAL GENERAL Preliminary Draft INTRODUCTION Purposes of the Civil Affairs Handbook. International Law places upon an occupying power the obligation and responsibility for establishing government and maintaining civil order in the areas occupied. The basic purposes of civil affairs officers are thus (l) to as- sist the Commanding General of the combat units by quickly establishing those orderly conditions which will contribute most effectively to the conduct of military operations, (2) to reduce to a minimum the human suffering and the material damage resulting from disorder and (3) to create the conditions which will make it possible for civilian agencies to function effectively. The preparation of Civil Affairs Handbooks is a part of the effort of the War Department to carry out this obligation as efficiently and humanely as is possible. The Handbooks do not deal with planning or policy. They are rather ready reference source books of the basic factual information needed for planning and policy making. Public Health and Sanitation in Greece. As a result of the various occupations, Greece presents some extremely difficult problems in health and sanitation. The material in this section was largely prepared by the MILBANK MEMORIAL FUND and the MEDICAL INTELLI- GENCE BRANCH OF THE OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL. If additional data on current conditions can be obtained, it willJse incorporated in the final draft of the handbook for Greece as a whole. -

The History of Theater

The History of Theater Summer Schools for Greek children, children from European high Schools and from Schools in America, Australia and Asia The project “Academy of Plato: Development of Knowledge and innovative ideas” is co-financed from National and European funds through the Operational Programme “Education and Lifelong Learning” The origin of Greek Drama • Drama originates from religious rituals. • It was connected, already from the start, with the cult of Dionysus. RELIGIOUS RITUALS • Argos - Samos: The ritual enactment of the wedding of Zeus and Hera. • Crete: The ritual enactment of the birth of Zeus • Delphi : The ritual enactment of Apollo’s fight with the Dragon Python by adolescents. Vase depicting the wedding of Zeus and Hera The wedding of Zeus and Hera Palazzo Medici Florence DIONYSUS • God of the grape and the wine • He incarnates the season cycle of the year and the eternal cycle of life and death. Vase depicting Dionysus Louvre Museum Vase depicting Dionysus as a youth Louvre Museum “Bacchus”, Michelangelo. “Dionysus and Eros”, Roman period “Bacchus”, Caravaggio THE CULT OF DIONYSUS • During the festivals of Dionysus, the followers of the god worshiped him in a state of ritual madness and ecstatic frenzy. Ecstasy • A basic feature of Dionysus cult was ecstasy . • The worshippers of the God were disguised wearing animal skin, have the dregs of wine spread all over their faces, wearing crowns of ivy, tails , beards or horns like the followers of the god, the Satyrs. • The worshippers identified themselves emotionally with the satyrs. This is the first step towards the birth of drama. “Satyr”, red figure kylix “Dionysian procession”, Red figure vase New Orleans festival “Dionysus’ parade” Valencia,Spain “The festival of Dionysus” Athens and Dionysus The time of drama performances • Drama performances took place during the festivities in honor of Dionysus , bound to their religious origin. -

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3930-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3930-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Greeting ................................................................................... ix Lidija Pliberšek Foreword .................................................................................................. xi Julie Rugg Acknowledgements ................................................................................ xiii List of Illustrations ............................................................................... xvii Introduction ........................................................................................ xxvii Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Part One: Funerary Monuments Inspired by the Art of Antiquity Chapter One ............................................................................................. -

Pico Della Mirandola Descola Gardner Eco Vernant Vidal-Naquet Clément

George Hermonymus Melchior Wolmar Janus Lascaris Guillaume Budé Peter Brook Jean Toomer Mullah Nassr Eddin Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh) Jerome of Prague John Wesley E. J. Gold Colin Wilson Henry Sinclair, 2nd Baron Pent... Olgivanna Lloyd Wright P. L. Travers Maurice Nicoll Katherine Mansfield Robert Fripp John G. Bennett James Moore Girolamo Savonarola Thomas de Hartmann Wolfgang Capito Alfred Richard Orage Damião de Góis Frank Lloyd Wright Oscar Ichazo Olga de Hartmann Alexander Hegius Keith Jarrett Jane Heap Galen mathematics Philip Melanchthon Protestant Scholasticism Jeanne de Salzmann Baptist Union in the Czech Rep... Jacob Milich Nicolaus Taurellus Babylonian astronomy Jan Standonck Philip Mairet Moravian Church Moshé Feldenkrais book Negative theologyChristian mysticism John Huss religion Basil of Caesarea Robert Grosseteste Richard Fitzralph Origen Nick Bostrom Tomáš Štítný ze Štítného Scholastics Thomas Bradwardine Thomas More Unity of the Brethren William Tyndale Moses Booker T. Washington Prakash Ambedkar P. D. Ouspensky Tukaram Niebuhr John Colet Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī Panjabrao Deshmukh Proclian Jan Hus George Gurdjieff Social Reform Movement in Maha... Gilpin Constitution of the United Sta... Klein Keohane Berengar of Tours Liber de causis Gregory of Nyssa Benfield Nye A H Salunkhe Peter Damian Sleigh Chiranjeevi Al-Farabi Origen of Alexandria Hildegard of Bingen Sir Thomas More Zimmerman Kabir Hesychasm Lehrer Robert G. Ingersoll Mearsheimer Ram Mohan Roy Bringsjord Jervis Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III Alain de Lille Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud Honorius of Autun Fränkel Synesius of Cyrene Symonds Theon of Alexandria Religious Society of Friends Boyle Walt Maximus the Confessor Ducasse Rāja yoga Amaury of Bene Syrianus Mahatma Phule Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Qur'an Cappadocian Fathers Feldman Moncure D. -

Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19Th-Century Central Balkans

Portland State University PDXScholar International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations International & Global Studies 9-2020 Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans Evguenia Davidova Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/is_fac Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, and the Social History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Davidova, E. (2020). Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 31(1), 48-67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in International & Global Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Evguenia Davidova Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19th-Century Central Balkans Abstract: Tis article compares the geographic and social mobility of two “lesser known” groups of workers: merchants’ assistants and maidservants. By combining labor mobility, class, and gender as categories of analysis, it suggests that such examples of temporary and return migration opened up new economic possibilities while at the same time reinforcing patriarchal order and increasing social inequality. Such transformative social practice is placed within the broader socio-economic and political fabric of the late Otto man and post-Ottoman Balkans during the “long 19th century.” Key Words: Balkans, commercial networks, domestic servants, labor mobil- ity, migration Troughout the 19th century, the Balkans faced profound economic, social, polit- ical, and cultural changes. -

Pages on C.P. Cavafy Published by Brandl & Schlesinger Pty Ltd PO Box 127 Blackheath NSW 2785 Tel (02) 4787 5848 Fax (02) 4787 5672

MODERN GREEK STUDIES (AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND) Volume 11, 2003 A Journal for Greek Letters Pages on C.P. Cavafy Published by Brandl & Schlesinger Pty Ltd PO Box 127 Blackheath NSW 2785 Tel (02) 4787 5848 Fax (02) 4787 5672 for the Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia and New Zealand (MGSAANZ) Department of Modern Greek University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia Tel (02) 9351 7252 Fax (02) 9351 3543 E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1039-2831 Copyright in each contribution to this journal belongs to its author. © 2003, Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Typeset and design by Andras Berkes Printed by Southwood Press, Australia MODERN GREEK STUDIES ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND (MGSAANZ) ETAIREIA NEOELLHNIKWN SPOUDWN AUSTRALIAS KAI NEAS ZHLANDIAS President: Michalis Tsianikas, Flinders University Vice-President: Anthony Dracoupoulos, University of Sydney Secretary: Thanassis Spilias, La Trobe University, Melbourne Treasurer: Panayota Nazou, University of Sydney, Sydney MGSAANZ was founded in 1990 as a professional association by those in Australia and New Zealand engaged in Modern Greek Studies. Membership is open to all interested in any area of Greek studies (history, literature, culture, tradition, economy, gender studies, sexualities, linguistics, cinema, Diaspora, etc). -

INFO KIT for Partners

European Solidarity Corps Guide Call 2019, Round 1, European Solidarity Corps - Volunteering Projects REQUIREMENTSWAVES III IN TERMS OF DISSEMINATION AND EXPLOITATION We Are Volos’ EvS III INFO KITGENERAL for partners QUALITATIVE REQUIREMENTS ApplicantsMunicipality of Volos for funding GREECE under the European Solidarity Corps are required to consider dissemination and exploitation KEKPA-DIEK Municipal activitiesEnterprise of Social Protection and Solidarity at the application stage,– during their activity and after the activity has finished. This section gives an overview of theMunicipal Institute of Vo basic requirementscational Training laid down for the European Solidarity Corps. http://www.kekpa.gr Dissemination and exploitation is one of the award criteria on which the application will be assessed. For all project types, Contact KEKPA-DIEKs projects application office: KEKPA-DIEK of the Municipality of Volos, GREECE. 22-26 Proussis str., GRreporting-38446, Nea Ionia VOLOS, Greece. Tel: +30 24210 on the activities61600. Email: carried out and to share the results inside and outside participating organisations will be [email protected] ; [email protected] Contact KEKPArequested-DIEKS coordinator of Volunteering activities at final stage.: Tel: +30 24210 35555. Email: [email protected] VISIBILITY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AND OF THE EUROPEAN SOLIDARITY CORPS Volos, 01.2019 Editing: Spyros Iatropoulos, Sociologist BeneficiariesProject department of KEKPA shall always-DIEK use the European emblem (the 'EU flag') and the name of the European Union spelled out in full in all communication and promotiona1l material. The preferred option to communicate about EU funding through the European Solidarity Corps is to write 'Co-funded by the European Solidarity Corps of the European Union' next to the EU emblem. -

The Representation of Women in the Novels of Gregorios Xenopoulos

THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN THE NOVELS OF GREGORIOS XENOPOULOS by MARIA HADJITHEODOROU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies The University of Birmingham August 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The present study aims to explore the position of women and their role in the domestic and public realm as presented by the Greek prose writer Gregorios Xenopoulos (1867 – 1951). The study will be divided into two chapters. In the first chapter, after having discussed the social context of the last quarter of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, I will examine and analyze women‟s position in Greek society as presented in Xenopoulos‟s novels, with special emphasis on the impact of the feminist movement on marriage and motherhood, education and work. Also, there will be a comparison of the Athenian and Zakynthian novels. In the second chapter, I intend to analyze the presentation of the physical appearance of female characters regarding facial and other physical characteristics, looking also at dress and hairstyles. -

Greek Banking in Constantinople, 1850-1881

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Greek banking in Constantinople, 1850-1881. Exertzoglou, Haris H A The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 to Angelo.. List of contents List of Tables p • I-Ill Abbreviations p • IV Acknowledgements p . V Introduction p.VI-VIII Part I Chapter I:The 19th century Ottoman empire;the economic landscape.