Circuits of Mobile Workers in the 19Th-Century Central Balkans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

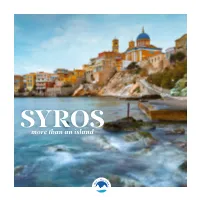

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

The Ottoman Middle East

The Ottoman Middle East Studies in Honor of Amnon Cohen Edited by Eyal Ginio and Elie Podeh LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24613-3 CONTENTS List of Illustrations .......................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... ix List of Contributors ........................................................................................ xi Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Eyal Ginio and Elie Podeh The Ottoman Empire and Europe ............................................................. 9 Bernard Lewis PART ONE OTTOMAN PALESTINE King Solomon or Sultan Süleyman? .......................................................... 15 Rachel Milstein The Renovations of Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) in Jerusalem ................................................................................................. 25 Khader Salameh Ottoman Intelligence Gathering during Napoleon’s Invasion of Egypt and Palestine .............................................................................. 45 Dror Zeʿevi A Note on ʿAziz (Asis) Domet: A Pro-Zionist Arab Writer ................ 55 Jacob M. Landau PART TWO OTTOMAN EGYPT AND THE FERTILE CRESCENT Un territoire « bien gardé » du sultan ? Les Ottomans dans leur vilâyet de Basra, 1565–1568 ..................................................................... -

The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ IOANNA PEPELASIS MINOGLOU Athens University of Economics ABSTRACT This paper analyses the organizational makeup and financial techniques of Greek Diaspora banking during its golden era in Constantinople, circa 1840-1881. It is argued that this small group of bankers had a flexible style of business organization which included informal operations. Well embedded into the network of international high finance, these bankers facilitated the integration of Constantinople into the Western European capital markets -during the early days of Western financial presence in the Ottoman Empire- by developing an ingenious for the standards of the time and place method for the internationalization of the financial instruments of the Internal Ottoman Public Debt. 1 ‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ 1 Greek Diaspora bankers are among the lesser known ethnic minority groups in the history of international finance. Tight knit but cosmopolitan, Greek Diaspora banking sprang within the international mercantile community of Diaspora Greeks which was based outside Greece and specialized in the long distance trade in staples. By the first half of the nineteenth century it operated an advanced network of financial transactions spreading from Odessa, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria in the East to Leghorn, Marseilles, Paris, and London in the West.2 More specifically, circa 1840-1881, in Constantinople, Greek Diaspora bankers3 attained an elite status within the local community through their specialization in the financing of the Ottoman Public Debt. -

Facing the Sea: the Jews of Salonika in the Ottoman Era (1430–1912)

Facing the Sea: The Jews of Salonika in the Ottoman Era (1430–1912) Minna Rozen Afula, 2011 1 © All rights reserved to Minna Rozen 2011 No part of this document may be reproduced, published, stored in an electronic database, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, for any purpose, without the prior written permission of the author ([email protected]). 2 1. Origins, Settlement and Heyday, 1430–1595 Jews resided in Salonika many centuries before the Turkic tribes first made their appearance on the borders of Western civilization, at the Islamic world’s frontier. In fact, Salonika was one of the cities in whose synagogue the apostle Paul had preached Jesus’ teachings. Like many other Jewish communities is this part of the Roman (and later the Byzantine) Empire, this had been a Greek-speaking community leading its life in much the same way as the Greek pagans, and later, the Christian city dwellers around them. The Ottoman conquest of Salonika in 1430 did little to change their lifestyle. A major upheaval did take place, however, with the Ottoman takeover of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, the Conqueror (Fatih in Turkish), aimed to turn the former Byzantine capital into the hub of his Empire, a world power in its own right on a par with such earlier grand empires as the Roman and the Persian. To that effect, he ordered the transfer of entire populations— Muslims, Greeks, and Jews—from other parts of his empire to the new capital in order to rebuild and repopulate it. -

I TURKEY and the RESCUE of JEWS DURING the NAZI ERA: a RE-APPRAISAL of TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS in TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS in OCCUPIED FRANCE

TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A REAPPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE by I. Izzet Bahar B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, 1974 M.Sc. in Electrical Engineering, Bosphorus University, Istanbul, 1977 M.A. in Religious Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Art and Sciences in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cooperative Program in Religion University of Pittsburgh 2012 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by I. Izzet Bahar It was defended on March 26, 2012 And approved by Clark Chilson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Religious Studies Seymour Drescher, PhD, University Professor, History Pınar Emiralioglu, PhD, Assistant Professor, History Alexander Orbach, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Adam Shear, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies ii Copyright © by I. Izzet Bahar 2012 iii TURKEY AND THE RESCUE OF JEWS DURING THE NAZI ERA: A RE-APPRAISAL OF TWO CASES; GERMAN-JEWISH SCIENTISTS IN TURKEY & TURKISH JEWS IN OCCUPIED FRANCE I. Izzet Bahar, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This study aims to investigate in depth two incidents that have been widely presented in literature as examples of the humanitarian and compassionate Turkish Republic lending her helping hand to Jewish people who had fallen into difficult, even life threatening, conditions under the racist policies of the Nazi German regime. The first incident involved recruiting more than one hundred Jewish scientists and skilled technical personnel from German-controlled Europe for the purpose of reforming outdated academia in Turkey. -

Civil Affairs Handbook on Greece

Preliminary Draft CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK on GREECE feQfiJtion Thirteen on fcSSLJC HJI4LTH 4ND S 4 N 1 T £ T I 0 N THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE PROVOST MARSHAL GENERAL Preliminary Draft INTRODUCTION Purposes of the Civil Affairs Handbook. International Law places upon an occupying power the obligation and responsibility for establishing government and maintaining civil order in the areas occupied. The basic purposes of civil affairs officers are thus (l) to as- sist the Commanding General of the combat units by quickly establishing those orderly conditions which will contribute most effectively to the conduct of military operations, (2) to reduce to a minimum the human suffering and the material damage resulting from disorder and (3) to create the conditions which will make it possible for civilian agencies to function effectively. The preparation of Civil Affairs Handbooks is a part of the effort of the War Department to carry out this obligation as efficiently and humanely as is possible. The Handbooks do not deal with planning or policy. They are rather ready reference source books of the basic factual information needed for planning and policy making. Public Health and Sanitation in Greece. As a result of the various occupations, Greece presents some extremely difficult problems in health and sanitation. The material in this section was largely prepared by the MILBANK MEMORIAL FUND and the MEDICAL INTELLI- GENCE BRANCH OF THE OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL. If additional data on current conditions can be obtained, it willJse incorporated in the final draft of the handbook for Greece as a whole. -

The Passion of Max Von Oppenheim Archaeology and Intrigue in the Middle East from Wilhelm II to Hitler

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/163 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Lionel Gossman is M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Romance Languages (Emeritus) at Princeton University. Most of his work has been on seventeenth and eighteenth-century French literature, nineteenth-century European cultural history, and the theory and practice of historiography. His publications include Men and Masks: A Study of Molière; Medievalism and the Ideologies of the Enlightenment: The World and Work of La Curne de Sainte- Palaye; French Society and Culture: Background for 18th Century Literature; Augustin Thierry and Liberal Historiography; The Empire Unpossess’d: An Essay on Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall”; Between History and Literature; Basel in the Age of Burckhardt: A Study in Unseasonable Ideas; The Making of a Romantic Icon: The Religious Context of Friedrich Overbeck’s “Italia und Germania”; Figuring History; and several edited volumes: The Charles Sanders Peirce Symposium on Semiotics and the Arts; Building a Profession: Autobiographical Perspectives on the Beginnings of Comparative Literature in the United States (with Mihai Spariosu); Geneva-Zurich-Basel: History, Culture, and National Identity, and Begegnungen mit Jacob Burckhardt (with Andreas Cesana). He is also the author of Brownshirt Princess: A Study of the ‘Nazi Conscience’, and the editor and translator of The End and the Beginning: The Book of My Life by Hermynia Zur Mühlen, both published by OBP. -

Tex Output 2005.03.22:1401

Chapter 9 the greater part of Macedonia, most of Thrace, and an enclave surrounding the city of Smyrna (I˙zmir).85 Territorial expansion meant demographic growth as well. Yet, far from dissipating the country’s problems, the ongoing military activity, entailing constant expenditures, contributed little by way of a solution. Indeed, the impressive accomplishments of the Macedonian wars and World War I lost some of their luster when the Turks managed to drive the Greeks out of Smyrna in 1922.86 While Smyrna was still burning, tens of thousands of Greek refugees fled from Anatolia to territories under Greek control. The Treaty of Lausanne restored eastern Thrace to Turkey and mandated forced population exchanges between the two states. According to one source, 1.5 million refugees settled in Greece in the aftermath of the First World War.87 85 On the role of the megali idea in the development of the Greek state, see G. Augustinos, “The Dynamics of Modern Greek Nationalism: The Great Idea and the Macedonian Problem,” East European Quarterly 6, no. 4 (1973), pp. 444y453; A.A.M. Bryer, “The Great Idea,” History Today, 15, no. 3 (1965), pp. 513y547; D. Dakin, “The Greek Unification and the Italian Risorgimento Compared,” Balkan Studies, 10, no. 1 (1969), pp. 1y10; idem, The Greek Struggle in Macedonia 1897y1913; J.S. Koliopoulos, Brigands with a Cause: Brigandage and Irredentism in Modern Greece 1821y1912 (Oxford, 1987); T.G. Tasios, The Megali Idea and the Greek-Turkish War of 1897: The Impact of the Cretan Problem on Greek Irredentism 1866y1897 (New York, 1984); Veremis, “National State to Stateless Nation, 1821y1910,” pp. -

Jewish Studies at the Central European University VIII 2011–2016

Jewish Studies at the Central European University VIII 2011–2016 I II Jewish Studies at the Central European University VIII 2011–2016 Edited by Carsten Wilke, András Kovács, and Michael L. Miller Jewish Studies Project Central European University Budapest III © Central European University, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication my be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the permission of the publisher. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to the Jewish Studies Project of the Central European University H–1051 Budapest, Nádor u. 9. Hungary Copy editing by Ilse Josepha Lazaroms Cover László Egyed Printed by Prime Rate Kft, Hungary IV TABLE OF CONTENTS CarsTen Wilke Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 SocIal HIstoRY Jana VObeckÁ Jewish Demographic Advantage: Low Mortality among Nineteenth-Century Bohemian Jews ...................................................... 7 VicTOR KaradY Jews in the Hungarian Legal Professions and among Law Students from the Emancipation until the Shoah ............................................................ 23 GÁBOR KÁDÁR and ZOLTÁN VÁgi Forgotten Tradition: The Morphology of Antisemitic Mass Violence in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Hungary ............................................... 55 MODERN EXemPlaRS ShlOMO Avineri Karl Marx’s Jewish Question(s) ...................................................................... -

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art

Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Ancient Greek Art and European Funerary Art Edited by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Evangelia Georgitsoyanni and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3930-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3930-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Greeting ................................................................................... ix Lidija Pliberšek Foreword .................................................................................................. xi Julie Rugg Acknowledgements ................................................................................ xiii List of Illustrations ............................................................................... xvii Introduction ........................................................................................ xxvii Evangelia Georgitsoyanni Part One: Funerary Monuments Inspired by the Art of Antiquity Chapter One ............................................................................................. -

For the Sake of My Brothers: the Great Fire of Salonika (1917) and the Mobilisation of Diaspora Jewry on Behalf of the Victims*

For the Sake of My Brothers: The Great Fire of Salonika (1917) and the Mobilisation of Diaspora Jewry on Behalf of the Victims* Minna Rozen** Introduction The Great Fire of Salonika has already been studied and discussed from a number of perspectives, primarily the tremendous damage caused to the city’s Jewish community and the impact on its standing;1 the fire as a turning point in Salonika’s urban history;2 and the plausibility of the conspiracy * This article was translated from the Hebrew original by Karen Gold. Many thanks to Prof. Rika Benveniste for writing the Greek abstract, and to Dr. Evanghelos A. Heki- moglou for his valuable comments. ** Minna Rozen is a professor emerita of the University of Haifa. 1. Ρένα Μόλχο, Οι Εβραίοι της Θεσσαλονίκης 1856-1919: Μια ιδιαίτερη κοινότητα (Θεσσαλονίκη: Θεμέλιο, 2001) [Rena Molho, The Jews of Salonika, 1856-1919: A Special Community (Salonika: Themelio, 2001)], 120-122; Vilma Hastaoglou-Martinidis, ‘A Mediterranean City in Transition: Thessaloniki between the Two World Wars’, Facta Universitatus, Architecture and Civil Engineering 1 (1997): 495-507; Rena Molho, ‘On the Jewish community of Salonica after the Fire of 1917: An Unpublished Memoir and Other Documents from the Papers of Henry Morgenthau’, in The Jewish Community of South- eastern Europe from the Fifteenth Century to the End of World War II (Thessaloniki: In- stitute for Balkan Studies, 1997), 147-174; Gila Hadar, ‘Régie Vardar: A Jewish “Garden City” in Thessaloniki (1917-1943)’ (paper presented at 7th International Conference on Urban History: European City in Comparative Perspective, Panteion University, Athens- Piraeus, Greece, 27-30 October 2004); Vilma Hastaoglou-Martinidis, ‘Urban Aesthetics and National Identity: The Refashioning of Eastern Mediterranean Cities between 1900 and 1940’, Planning Perspectives 26.2 (2011): 153-182, esp. -

INFO KIT for Partners

European Solidarity Corps Guide Call 2019, Round 1, European Solidarity Corps - Volunteering Projects REQUIREMENTSWAVES III IN TERMS OF DISSEMINATION AND EXPLOITATION We Are Volos’ EvS III INFO KITGENERAL for partners QUALITATIVE REQUIREMENTS ApplicantsMunicipality of Volos for funding GREECE under the European Solidarity Corps are required to consider dissemination and exploitation KEKPA-DIEK Municipal activitiesEnterprise of Social Protection and Solidarity at the application stage,– during their activity and after the activity has finished. This section gives an overview of theMunicipal Institute of Vo basic requirementscational Training laid down for the European Solidarity Corps. http://www.kekpa.gr Dissemination and exploitation is one of the award criteria on which the application will be assessed. For all project types, Contact KEKPA-DIEKs projects application office: KEKPA-DIEK of the Municipality of Volos, GREECE. 22-26 Proussis str., GRreporting-38446, Nea Ionia VOLOS, Greece. Tel: +30 24210 on the activities61600. Email: carried out and to share the results inside and outside participating organisations will be [email protected] ; [email protected] Contact KEKPArequested-DIEKS coordinator of Volunteering activities at final stage.: Tel: +30 24210 35555. Email: [email protected] VISIBILITY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION AND OF THE EUROPEAN SOLIDARITY CORPS Volos, 01.2019 Editing: Spyros Iatropoulos, Sociologist BeneficiariesProject department of KEKPA shall always-DIEK use the European emblem (the 'EU flag') and the name of the European Union spelled out in full in all communication and promotiona1l material. The preferred option to communicate about EU funding through the European Solidarity Corps is to write 'Co-funded by the European Solidarity Corps of the European Union' next to the EU emblem.