Greco-Turkish Railway Connection: Illusions and Bargains in the Late Nineteenth Century Balkans*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Results Regarding the Rock Falls of December 17, 2009 at Tempi, Greece

Bulletin of the Geological Soci- Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής ety of Greece, 2010 Εταιρίας, 2010 Proceedings of the 12th Interna- Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρί- tional Congress, Patras, May, ου, Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 2010 PRELIMINARY RESULTS REGARDING THE ROCK FALLS OF DECEMBER 17, 2009 AT TEMPI, GREECE Christaras B.1, Papathanassiou G.1, Vouvalidis K.2, Pavlides S.1 1 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Geology, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Physical and Environmental Geography, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected] Abstract On December 17, 2009, a large size rock fall generated at the area of Tempi, Central Greece causing one casualty. In particular, a large block was detached from a high of 70 meters and started to roll downslope and gradually became a rock slide. About 120 tones of rock material moved downward to the road resulting to the close of the national road. Few days after the slope failure, a field survey organized by the Department of Geology, AUTH took place in order to evaluate the rock fall hazard in the area and to define the triggering causal factors. As an out- come, we concluded that the heavily broken rock mass and the heavy rain-falls, of the previous days, contribute significantly to the generation of the slope failure. The rocky slope was limited stable and the high joint water pressure caused the failure of the slope. Key words: rock fall, Tempi, engineering geology, hazard, Greece 1. Introduction A rock fall is a fragment of rock detached by sliding, toppling or falling that falls along a vertical or sub-vertical cliff, proceeds down slope by bouncing and flying along ballistic trajectories or by rolling on talus or debris slopes (Varnes, 1978). -

Grand Tour of Greece

Grand Tour of Greece Day 1: Monday - Depart USA Depart the USA to Greece. Your flight includes meals, drinks and in-flight entertainment for your journey. Day 2: Tuesday - Arrive in Athens Arrive and transfer to your hotel. Balance of the day at leisure. Day 3: Wednesday - Tour Athens Your morning tour of Athens includes visits to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Panathenian Stadium, the ruins of the Temple of Zeus and the Acropolis. Enjoy the afternoon at leisure in Athens. Day 4: Thursday - Olympia CORINTH Canal (short stop). Drive to EPIDAURUS (visit the archaeological site and the theatre famous for its remarkable acoustics) and then on to NAUPLIA (short stop). Drive to MYCENAE where you visit the archaeological site, then depart for OLYMPIA, through the central Peloponnese area passing the cities of MEGALOPOLIS and TRIPOLIS arrive in OLYMPIA. Dinner & Overnight. Day 5: Friday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of OLYMPIA. Drive via PATRAS to RION, cross the channel to ANTIRION on the "state of the art" new suspended bridge considered to be the longest and most modern in Europe. Arrive in NAFPAKTOS, then continue to DELPHI.. Dinner & Overnight. Day 6: Saturday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of Delphi. Rest of the day at leisure. Dinner & Overnight in DELPHI. Day 6: Sunday – Kalambaka In the morning, start the drive by the central Greece towns of AMPHISSA, LAMIA and TRIKALA to KALAMBAKA. Afternoon visit of the breathtaking METEORA. Dinner & Overnight in KALAMBAKA. Day 7: Monday - Thessaloniki Drive by TRIKALA and LARISSA to the famous, sacred Macedonian town of DION (visit).Then continue to THESSALONIKI, the largest town in Northern Greece. -

(Selido ΤΟϜϟϣ 4

Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Patras, May, 2010 GROUNDWATER QUALITY OF THE AG. PARASKEVI/TEMPI VALLEY KARSTIC SPRINGS - APPLICATION OF A TRACING TEST FOR RESEARCH OF THE MICROBIAL POLLUTIO (KATO OLYMPOS/NE THESSALY) Stamatis G. Agricultural University of Athens, Institute of Mineralogy-Geology, Iera Odos 75, GR-118 55 Athens, [email protected] . Abstract The study of the Kato Olympos karst system, based on the implementation of tracer tests and hydro- chemical analyses, is aimed at the investigation of surface-groundwater interaction, the delineation of the catchment area and the detection of the surface microbial source contamination of the Tempi karst springs. The study area is formed by intensively karstified carbonate rocks, metamorphic for- mations, Neogene sediments and Quaternary deposits. The significant karst aquifer discharges through karst springs in Tempi valley and in Pinios riverbed. The karst springs present important seasonal fluctuations in discharge rate, moderate mineralization with TDS between 562 to 630 mg/l + + - - and they belong to Ca-HCO3 water type. The inorganic pollution indicators, such as Na , K , Cl , NO3 + 3 , NH4 , PO4 , show low concentrations and do not reveal any surface influences. On the other hand, the presence of microbial parameters in karst springs proclaims the high rate of microbial contami- nation of karst aquifer. Tracer tests reveal hydraulic connection between the surface waters of Xirorema – Rapsani basin and the karst aquifer. The high values of groundwater flow velocity upwards of 200 m/h, show the good karstification rate of the carbonate formations and the cavy structure dom- inated in the study area, as well as the low self purification capability of the karst aquifer. -

The Emigration of Muslims from the Greek State in the 19Th Century

BALCANICA POSNANIENSIA XXVII Poznań 2020 THE EMIGRATION OF MUSLIMS FROM THE GREEK STATE 1 IN THE 19TH CENTURy. AN OUTLINE kr z y s z t o f Po P e k Abstract. Modern Greek statehood began to take shape with the War of Independence that broke out in 1821 and continued with varying intensity for the next years. As a result of these events, the Greeks cast of the foreign rule, which for many not only meant separation from the Ottoman Empire, but also the expulsion of Muslims living in these lands. During the uprising, about 25 000 Muslims lost their lives, and a similar number emigrated from the territory of the future Greek state. The next great exodus of Muslims from Greek lands was related to the an- nexation of Thessaly by the Hellenic Kingdom, which was to a larger extent spread over time. Since the region was incorporated into Greece until the beginning of the 20th century, the 40 000-strong Islamic community had virtually disappeared. Author: Krzysztof Popek, Jagiellonian University, Faculty of History, World Contemporary History Department, Gołębia st. 13, 31-007 Cracow, Poland, [email protected], OrciD iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5864- 5264 Keywords: Greece, 19th century, Muslim minority, migrations, Thessaly, Greek War of Independence Balcanica Posnaniensia. Acta et studia, XXVII, Poznań 2020, Wydawnictwo Wydziału Historii UAM, pp. 97– 122, ISBN 978-83-66355-54-5, ISSN 0239-4278. English text with summaries in English and Polish. doi.org/10.14746/bp.2020.27.7 INTRODUCTION Although Greece itself does not want to be treated as one of the Balkan countries, the Greek experience of the period of building its own nation-statehood is character- istic of this region. -

Greece Page 1 of 17

Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Greece Page 1 of 17 Greece Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 6, 2007 Greece is a constitutional republic and multiparty parliamentary democracy, with an estimated population of 11 million. In March 2004 the New Democracy Party won the majority of seats in the unicameral Vouli (parliament) in free and fair elections, and Konstantinos Karamanlis became the prime minister. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, there were problems in several areas. The following human rights abuses were reported: abuse by security forces, particularly of illegal immigrants and Roma; overcrowding and harsh conditions in some prisons; detention of undocumented migrants in squalid conditions; limits on the ability of ethnic minorities to self-identify; restrictions on freedom of speech; restrictions and administrative obstacles faced by members of non-Orthodox religions; detention and deportation of unaccompanied or separated immigrant minors, including asylum seekers; domestic violence against women; trafficking in persons; discrimination against ethnic minorities and Roma; substandard living conditions for Roma; inadequate access to schools for Romani children; and child exploitation in nontraditional labor. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed any politically motivated killings; however, in September there were reports that coast guard authorities threw detained illegal migrants overboard and six of them drowned. -

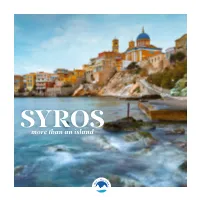

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

The Bank of Constantinople Was a Shareholder in the Tobacco

‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ IOANNA PEPELASIS MINOGLOU Athens University of Economics ABSTRACT This paper analyses the organizational makeup and financial techniques of Greek Diaspora banking during its golden era in Constantinople, circa 1840-1881. It is argued that this small group of bankers had a flexible style of business organization which included informal operations. Well embedded into the network of international high finance, these bankers facilitated the integration of Constantinople into the Western European capital markets -during the early days of Western financial presence in the Ottoman Empire- by developing an ingenious for the standards of the time and place method for the internationalization of the financial instruments of the Internal Ottoman Public Debt. 1 ‘Ethnic Minority Groups in International Banking: Greek Diaspora Banks of Constantinople and Ottoman State Finances, c.1840-1881’ 1 Greek Diaspora bankers are among the lesser known ethnic minority groups in the history of international finance. Tight knit but cosmopolitan, Greek Diaspora banking sprang within the international mercantile community of Diaspora Greeks which was based outside Greece and specialized in the long distance trade in staples. By the first half of the nineteenth century it operated an advanced network of financial transactions spreading from Odessa, Constantinople, Smyrna, and Alexandria in the East to Leghorn, Marseilles, Paris, and London in the West.2 More specifically, circa 1840-1881, in Constantinople, Greek Diaspora bankers3 attained an elite status within the local community through their specialization in the financing of the Ottoman Public Debt. -

Structural Damage Prediction Under Seismic Sequence Using Neural Networks

COMPDYN 2021 8th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering M. Papadrakakis, M. Fragiadakis (eds.) Streamed from Athens, Greece, 27—30 June 2021 STRUCTURAL DAMAGE PREDICTION UNDER SEISMIC SEQUENCE USING NEURAL NETWORKS Petros C. Lazaridis1, Ioannis E. Kavvadias1, Konstantinos Demertzis 1, Lazaros Iliadis1, Antonios Papaleonidas1, Lazaros K. Vasiliadis1, Anaxagoras Elenas1 1Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace, Campus of Kimmeria, 67100 Xanthi, Greece e-mail: fpetrlaza1@civil, ikavvadi@civil, kdemertz@fmenr, liliadis@civil, papaleon@civil, lvasilia@civil, [email protected] Keywords: Seismic Sequence, Neural Networks, Repeated Earthquakes, Structural Damage Prediction, Artificial Intelligence, Intensity Measures Abstract. Advanced machine learning algorithms, such as neural networks, have the potential to be successfully applied to many areas of system modelling. Several studies have been al- ready conducted on forecasting structural damage due to individual earthquakes, ignoring the influence of seismic sequences, using neural networks. In the present study, an ensemble neural network approach is applied to predict the final structural damage of an 8-storey reinforced concrete frame under real and artificial ground motion sequences. Successive earthquakes con- sisted of two seismic events are utilised. We considered 16 well-known ground motion intensity measures and the structural damage that occurred by the first earthquake as the features of the machine-learning problem, while the final structural damage was the target. After the first seismic events and after the seismic sequences, both actual values of damage indices are calcu- lated through nonlinear time history analysis. The machine-learning model is trained using the dataset generated from artificial sequences. -

MIS Code: 5016090

“Developing Identity ON Yield, SOil and Site” “DIONYSOS” MIS Code: 5016090 Deliverable: 3.1.1 “Recording wine varieties & micro regions of production” The Project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and by national funds of the countries participating in the Interreg V-A “Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020” Cooperation Programme. 1 The Project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and by national funds of the countries participating in the Interreg V-A “Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020” Cooperation Programme. 2 Contents CHAPTER 1. Historical facts for wine in Macedonia and Thrace ............................................................5 1.1 Wine from antiquity until the present day in Macedonia and Thrace – God Dionysus..................... 5 1.2 The Famous Wines of Antiquity in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace ..................................................... 7 1.2.1 Ismaric or Maronite Wine ............................................................................................................ 7 1.2.2 Thassian Wine .............................................................................................................................. 9 1.2.3 Vivlian Wine ............................................................................................................................... 13 1.3 Wine in the period of Byzantium and the Ottoman domination ....................................................... 15 1.4 Wine in modern times ......................................................................................................................... -

Thessaly, Greece) K.-G

Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 9, 03049, 2007 SRef-ID: 1607-7962/gra/EGU2007-A-03049 © European Geosciences Union 2007 A Quantitave Archaeoseismological Study of the Great Theatre of Larissa (Thessaly, Greece) K.-G. Hinzen (1), S. Schreiber (1), R. Caputo (2), D. Liberatore (3), B. Helly (4), A. Tziafalias (5) (1) University of Cologne, Germany ([email protected]), (2) University of Ferrara, Italy ([email protected]), (3) University of Basilicata, Italy, (4) Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen "Jean-Pouilloux", Lyon, France, (5) Dept. of Prehistorical and Classical Antiquities, Larissa, Greece Larissa, the capital of Thessaly, is located in the eastern part of Central Greece, at the southern border of a Late Quarternary graben, the Tyrnavos Basin. Palaeoseis- mological, morphotectonic and geophysical investigations as well as historical and instrumental records show evidences for seismic activity in this area. The investiga- tions documented the occurrence of several moderate to strong earthquakes during Holocene time. These active structures show recurrence intervals of few thousands of years. The historical and instrumental records suggest a period of seismic quiescence during the last 400 to 500 years. The present research, based on an archaeoseismo- logical keynote is a multi disciplinary approach to improve the knowledge on past earthquakes, which occurred in the area. This study focuses on damages on walls of the scene building of the Great Theatre of Larissa. The Theatre was built at the be- ginning of the 3rd century BC and consists of a semicircular auditorium, an almost circular arena and a main scene building. Archaeological and historical investigations document a partial destruction of the theatre during the 2nd-1st century BC. -

Civil Affairs Handbook on Greece

Preliminary Draft CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK on GREECE feQfiJtion Thirteen on fcSSLJC HJI4LTH 4ND S 4 N 1 T £ T I 0 N THE MILITARY GOVERNMENT DIVISION OFFICE OF THE PROVOST MARSHAL GENERAL Preliminary Draft INTRODUCTION Purposes of the Civil Affairs Handbook. International Law places upon an occupying power the obligation and responsibility for establishing government and maintaining civil order in the areas occupied. The basic purposes of civil affairs officers are thus (l) to as- sist the Commanding General of the combat units by quickly establishing those orderly conditions which will contribute most effectively to the conduct of military operations, (2) to reduce to a minimum the human suffering and the material damage resulting from disorder and (3) to create the conditions which will make it possible for civilian agencies to function effectively. The preparation of Civil Affairs Handbooks is a part of the effort of the War Department to carry out this obligation as efficiently and humanely as is possible. The Handbooks do not deal with planning or policy. They are rather ready reference source books of the basic factual information needed for planning and policy making. Public Health and Sanitation in Greece. As a result of the various occupations, Greece presents some extremely difficult problems in health and sanitation. The material in this section was largely prepared by the MILBANK MEMORIAL FUND and the MEDICAL INTELLI- GENCE BRANCH OF THE OFFICE OF THE SURGEON GENERAL. If additional data on current conditions can be obtained, it willJse incorporated in the final draft of the handbook for Greece as a whole. -

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Series B- 5922/31.12.2018

69941 GREEK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Series B- 5922/31.12.2018 TRUE COPY 69941 OF THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT Greek Government Gazette December 31st 2018 SERIES B Issue No. 5922 Β' 464/19-4-2010). DECISIONS 9. The provisions of ministerial decision “Natural Gas Dec. No 1314/2018 Licensing Regulation” ref. no. 178065 (Government Gazette Β' 3430/17.08.2018, hereinafter referred to as For the granting of a Natural Gas Distribution “Licensing Regulation”). License to the company under the trade name 10. The Tariffs Regulation for the Main Distribution “Gas Distribution Company Thessaloniki- Activity of distribution networks in Attica, Thessaloniki, Thessaly S.A.” and the distinctive title “EDA Thessaly and other Greece (Government Gazette Β' THESS”. 3067/26.09.2016) (hereinafter referred to as “Tariffs Regulation”). THE REGULATORY AUTHORITY FOR ENERGY 11. The RAE's Decision No 346/2016 on the Approval Taking into consideration the following: of the Tariff for the Charge of the Main Natural Gas 1. The provisions of Law 4001/2011 “For the Distribution Activity on Thessaloniki distribution network operation of the Energy Markets of Electricity and (Government Gazette Β' 3490/31.10.2016). Natural Gas, for Research, Production and transmission 12. The RAE's Decision No 347/2016 on the Approval networks of Hydrocarbons and other arrangements” of the Tariff for the Charge of the Main Natural Gas (Government Gazette A’179/22.08.2011), as amended Distribution Activity on Thessaly distribution network and in force (hereinafter referred to as “the Law”), and (Government Gazette Β'3537/03.11.2016). especially articles 13 and 80C thereof.