In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Scion James Murdoch Quits News Corp Board 1 August 2020

Media scion James Murdoch quits News Corp board 1 August 2020 Disney acquired most of the group's assets. James Murdoch, 47, has recently been critical of his father's business and its media coverage. In January, he denounced the climate change skepticism of some Murdoch media, citing coverage of the fires which devastated large parts of Australia. He has launched his own private holding company called Lupa Systems, which among other things has taken a stake in Vice Media. "We're grateful to James for his many years of James Murdoch, who has resigned from News Corp, has service to the company. We wish him the very best been critical of the business and its media coverage in his future endeavors," said Rupert Murdoch, executive chairman of News Corp and James's brother Lachlan Murdoch in a statement. Former 21st Century Fox chief executive James © 2020 AFP Murdoch, son of media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, has resigned from News Corp's board, according to a document released Friday by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). A letter sent by James Murdoch to the board said the decision was due to "disagreements over certain editorial content published by the company's news outlets and certain other strategic decisions." News Corp owns the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, The Times and the Sun newspapers among others, but not Rupert Murdoch's Fox News network. James Murdoch was once seen as his father's successor, but Friday's move reinforces his disengagement from the family media empire, which grew from a newspaper group in Australia. -

Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific

How the fossil fuel industry, News Corp, and the Federal Government hijacked the Black Summer bushfires to prevent action on climate change Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific Lead author Louis Brailsford Contributing authors Nikola Čašule Zachary Boren Tynan Hewes Edoardo Riario Sforza Design Olivia Louella Authorised by Kate Smolski, Greenpeace Australia Pacific, Sydney May 2020 www.greenpeace.org.au TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 6 2. The Black Summer bushfires 7 3. Deny, minimise, adapt: The response of the Morrison Government 9 Denial 9 Minimisation 10 Adaptation and resilience 11 4. Why disinformation benefits the fossil fuel industry 12 Business as usual 13 Protecting the coal industry 14 5. The influence of the fossil fuel lobby on government 16 6. Political donations and financial influence 19 7. News Corp’s disinformation campaign 21 News Corp and climate denialism 21 News Corp, the Federal Government and the fossil fuel industry 27 8. #ArsonEmergency: social media disinformation and the role of News Corp and the Federal Government 29 The facts 29 #ArsonEmergency 30 Explaining the persistence of #ArsonEmergency 33 Timeline: #ArsonEmergency, News Corp and the Federal Government 36 9. Case study – “He’s been brainwashed”: Attacking the experts 39 10. Case study – Matt Kean, the Liberal party minister who stepped out of line 41 11. Conclusions 44 End Notes 45 References 51 Dirty Power: Burnt Country 3 Greenpeace Australia Pacific EXECUTIVE SUMMARY stronger action to phase out fossil fuels, was aided by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp media empire, and a Australia’s 2019/20 Black coordinated campaign of social media disinformation. -

March 31 ACMA Eye Pa

8 March 31 - April 1, 2012 The Weekend Australian Financial Review www.afr.com News Pay TV piracy From `big problem' to `fixable' Porter changes view on severity Austar Key points Angus Grigg @ John Porter and Kim Williams lobbied to make pay TV piracy a specific criminal offence. Austar chief executive John Porter conceded on Friday piracy in the @ On Friday, Mr Porter said such pay TV industry was a major issue piracy was `not an endemic and may have cost his company long-term problem'. up to $17 million in some years. ªYeah, look, it is a big number,º Cottle as a threat to any NDS he told the Weekend Financial systems but without disturbing his Review. ªI acknowledge that piracy other hacking activities (as much was a significant problem but as possible),º Ms Gutman wrote. there is always a fix.º ªWe do not want Cottle in jail Mr Porter's comments come until he has a successor for the after The Australian Financial Irdeto hack.º Review published a series of Austar was one of Irdeto's main articles during the week detailing clients in Australia. Mr Porter how a News Corp subsidiary, NDS, would not comment on the email promoted a global wave of pay TV except to say: ªAvigail what's-her- piracy in the late 1990s. name was maybe a little too Austar and its smartcard excitable.º provider, Irdeto, were two of NDS's He also argued that it was in main targets. ªnobody's interestº to have the On Friday, Austar shareholders Irdeto platform hacked, as it had voted in favour of a takeover by also provided services to Foxtel's Foxtel, cementing its dominance satellite customers. -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

IN the COURT of CHANCERY of the STATE of DELAWARE CENTRAL LABORERS PENSION FUND, Plaintiff, V. NEWS CORPORATION, Defendant

EFiled: Mar 16 2011 4:28PM EDT Transaction ID 36513228 Case No. 6287- IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE ) CENTRAL LABORERS PENSION FUND, ) ) Plaintiff, ) C.A. No. v. ) ) NEWS CORPORATION, ) ) Defendant. ) COMPLAINT PURSUANT TO 8 DEL. C. §220 TO COMPEL INSPECTION OF BOOKS AND RECORDS Plaintiff Central Laborers Pension Fund (“Central Laborers”), as and for its Complaint, herein alleges, upon knowledge as to itself and its own actions, and upon information and belief as to all other matters, as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. In this action, plaintiff seeks to enforce its right to inspect certain corporate books and records of defendant News Corporation (“News Corp” or the “Company”), a Delaware corporation, pursuant to 8 Del. C. § 220 (“Section 220”). Plaintiff seeks to inspect these documents in order to investigate possible breaches of fiduciary duty on the part of News Corp’s Board of Directors, including its Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and controlling shareholder, Rupert Murdoch (“Murdoch”), in allowing Murdoch to cause News Corp to spend $675 million to buy Shine Group (“Shine”), a company controlled by Murdoch’s daughter, Elisabeth Murdoch (the “Transaction”), for no valid business purpose. Murdoch has made clear that an express purpose of the Transaction is to bring Elisabeth back to the family business—News Corp—and onto News Corp’s Board of Directors. 2. As set forth herein, plaintiff believes that News Corp has improperly agreed to enter into the Transaction with Murdoch’s daughter at terms unfair to the Company, and for the purpose of furthering Murdoch’s single-minded goal of maintaining his, and over the long-term, his family’s, control over his vast media empire, to the detriment of the Company. -

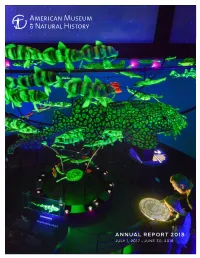

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 JULY 1, 2017 – JUNE 30, 2018 be out-of-date or reflect the bias and expeditionary initiative, which traveled to SCIENCE stereotypes of past eras, the Museum is Transylvania under Macaulay Curator in endeavoring to address these. Thus, new the Division of Paleontology Mark Norell to 4 interpretation was developed for the “Old study dinosaurs and pterosaurs. The Richard New York” diorama. Similarly, at the request Gilder Graduate School conferred Ph.D. and EDUCATION of Mayor de Blasio’s Commission on Statues Masters of Arts in Teaching degrees, as well 10 and Monuments, the Museum is currently as honorary doctorates on exobiologist developing new interpretive content for the Andrew Knoll and philanthropists David S. EXHIBITION City-owned Theodore Roosevelt statue on and Ruth L. Gottesman. Visitors continued to 12 the Central Park West plaza. flock to the Museum to enjoy the Mummies, Our Senses, and Unseen Oceans exhibitions. Our second big event in fall 2017 was the REPORT OF THE The Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth received CHIEF FINANCIAL announcement of the complete renovation important updates, including a magnificent OFFICER of the long-beloved Gems and Minerals new Climate Change interactive wall. And 14 Halls. The newly named Allison and Roberto farther afield, in Columbus, Ohio, COSI Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals will opened the new AMNH Dinosaur Gallery, the FINANCIAL showcase the Museum’s dazzling collections first Museum gallery outside of New York STATEMENTS and present the science of our Earth in new City, in an important new partnership. 16 and exciting ways. The Halls will also provide an important physical link to the Gilder All of this is testament to the public’s hunger BOARD OF Center for Science, Education, and Innovation for the kind of science and education the TRUSTEES when that new facility is completed, vastly Museum does, and the critical importance of 18 improving circulation and creating a more the Museum’s role as a trusted guide to the coherent and enjoyable experience, both science-based issues of our time. -

In 2005, Lachlan Murdoch Walked Away from a Worldwide Media Empire That Could Have Been His. Now, After Nearly a Decade of Exile

HEIR FORCE ONE HANDS ON After nearly nine years of pursuing his own life in Australia, Lachlan AKELA/CORBIS; AKELA/CORBIS; M Murdoch—shown here In 2005, Lachlan Murdoch walked away from a worldwide media during News Corp.’s ARK ARK stressful summer of empire that could have been his. Now, after nearly a decade of M 2011—may finally be ready to take the reins. exile, power struggles, and near-catastrophic scandals, the firstborn Opposite: A protester sets fire to a copy of son of Rupert is on the verge of claiming the News Corp. throne. the now-defunct News FROM LEFT: © © LEFT: FROM WINNING/REUTERS ANDREW of the World, 2011. By MICHAEL WOLFF 152 | TOWNANDCOUNTRYMAG.COM avowals of love, always as though no one else were in the room. The Mur- dochs were the Murdochs to the exclusion of everyone else. They shared FATHER AND SON, not only billions of dollars, a global power base, and a sense of utmost LOCKED in A WAR OF WillS destiny, but a failure to separate in any modern family way. They lived in a bubble—continents apart but tying up their yachts together at conve- AND EGO AND PriDE, nient moments as often as many other families get together for dinner. This was the political reality lived by such people as then News HAVE SUffERED GREATLY Corp. COO Peter Chernin, Fox News head Roger Ailes, and Fox in THE STANDOff. broadcasting chief Chase Carey (now president and COO of 21st Century Fox). These professional managers had been key players in transforming News Corp. -

It Failure and the Collapse of One.Tel

IT FAILURE AND THE COLLAPSE OF ONE.TEL David Avison and David Wilson ESSEC Business School, Cergy-Pontoise, France and University of Technology, Sydney, Australia Abstract: There are a number of cases about IS failure. However, few suggest that the IS failure led to the downfall of the business. This paper examines the information technology strategies employed by the high-profile Australian telecommunications company One. Tel Limited and assesses the extent to which a failure of those strategies may have contributed to, or precipitated, One.Tel's downfall. With increased reliance on technology in business and its sophistication, potentially catastrophic failures may be more common in the future One. Tel was founded in 1995 as an Australian telecommunication company and ceased trading in 2001. In the middle of 1999, the focus of the company changed towards the building of a global business, geared to the delivery of media content. We argue that the IT strategies operating within One. Tel were not adapted to meet the rapid growth that ensued. Further, we suggest that the information technology approaches that had served adequately in the early years were not appropriate for its later ambitions. Most importantly, we discuss the failure of its billing system in relation to published frameworks of IT failure as well as the importance of getting such basic systems right. We argue that these frameworks do not cover well the One. Tel case and we put forward a new category ofIT failure, that of 'business ethos' Key words: IS failure, One. Tel, IS strategy, Business ethos, Case study 1. -

News Corporation 1 News Corporation

News Corporation 1 News Corporation News Corporation Type Public [1] [2] [3] [4] Traded as ASX: NWS ASX: NWSLV NASDAQ: NWS NASDAQ: NWSA Industry Media conglomerate [5] [6] Founded Adelaide, Australia (1979) Founder(s) Rupert Murdoch Headquarters 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City, New York 10036 U.S Area served Worldwide Key people Rupert Murdoch (Chairman & CEO) Chase Carey (President & COO) Products Films, Television, Cable Programming, Satellite Television, Magazines, Newspapers, Books, Sporting Events, Websites [7] Revenue US$ 32.778 billion (2010) [7] Operating income US$ 3.703 billion (2010) [7] Net income US$ 2.539 billion (2010) [7] Total assets US$ 54.384 billion (2010) [7] Total equity US$ 25.113 billion (2010) [8] Employees 51,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions [9] Website www.newscorp.com News Corporation 2 News Corporation (NASDAQ: NWS [3], NASDAQ: NWSA [4], ASX: NWS [1], ASX: NWSLV [2]), often abbreviated to News Corp., is the world's third-largest media conglomerate (behind The Walt Disney Company and Time Warner) as of 2008, and the world's third largest in entertainment as of 2009.[10] [11] [12] [13] The company's Chairman & Chief Executive Officer is Rupert Murdoch. News Corporation is a publicly traded company listed on the NASDAQ, with secondary listings on the Australian Securities Exchange. Formerly incorporated in South Australia, the company was re-incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law after a majority of shareholders approved the move on November 12, 2004. At present, News Corporation is headquartered at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Ave.), in New York City, in the newer 1960s-1970s corridor of the Rockefeller Center complex. -

Fox Gets Exact Decision It Didn't Want on Sky Deal

Fox Gets Exact Decision It Didn't Want on Sky Deal thestreet.com /story/14336396/1/fox-gets-decision-it-didnt-want-on-sky-deal.html By Leon 10/10/2017 Lazaroff This wasn't the plan. Ten months ago, Rupert Murdoch's Twenty-First Century Fox Inc. (FOXA - Get Report) announced an agreement to acquire the 61% of British pay-TV giant Sky plc that it didn't already own in a transaction valued at £11.7 billion ($15.4 billion). The Murdochs have wanted to own all of Sky for years but were thwarted in 2011 after U.K. newspapers they owned were shown to have illegally obtained voice mails of celebrities, politicians and crime victims, including a murdered girl. Some six years later, the Murdochs are once again having to deflect attention about the internal workings of their company as they pursue the same goal of taking full ownership of a cable TV and internet provider that spans the U.K., Ireland, Germany, Austria and Italy. The U.K. regulator known as the Competition and Markets Authority said on Tuesday, Oct. 10, that it would examine the company's treatment of its employees both in the U.K. and in other countries amid a wider assessment of its corporate governance practices. In effect, this could include an examination of the company's conduct in connection with a sexual harassment lawsuit that led to the ouster of former Fox News chairman Roger Ailes, who died in May, as well as a series of harassment settlements the company made on behalf of Bill O'Reilly, the former Fox News host who was forced out in April. -

Downloads for Smartphones and MP3 Players

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2016 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-35769 NEWS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Delaware 46-2950970 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (212) 416-3400 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange On Which Registered Class A Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Class B Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Global Select Market Class A Preferred Stock Purchase Rights The NASDAQ Global Select Market Class B Preferred Stock Purchase Rights The NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

Efiled: Nov 20 2017 02:01PM EST Transaction ID 61379249 Case No. 2017-0833-AGB

EFiled: Nov 20 2017 02:01PM EST Transaction ID 61379249 Case No. 2017-0833-AGB IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE CITY OF MONROE EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM, derivatively on behalf of TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC., Plaintiff, v. RUPERT MURDOCH, LACHLAN MURDOCH, JAMES MURDOCH, C.A. No. _____________ CHARLES G. CAREY, DAVID F. DEVOE, RODERICK I. EDDINGTON, ROGER S. SILBERMAN, JACQUES A. NASSER, JAMES W. BREYER, JEFFREY W. UBBEN, VIET DINH, DELPHINE ARNAULT, TIDJANE THIAME, AND THE ESTATE OF ROGER AILES, Defendants, and TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC., Nominal Defendant. DECLARATION OF PROFESSOR LAWRENCE A. HAMERMESH, WIDENER UNIVERSITY DELAWARE LAW, IN SUPPORT OF SETTLEMENT 1 1. I respectfully submit this declaration in connection with the parties’ application for approval of the settlement reached in this matter involving Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. (“Fox”). In particular, I have reviewed the document reflecting the creation of the Fox News Workplace Professionalism and Inclusion Council (the “Council”) and related governance and compliance enhancements, to be put in place in response to allegations of harassment, discrimination, and retaliation at Fox News Channel (“Fox News”) (hereinafter, the “Council Agreement” or “Agreement”). 2. I submit this declaration to highlight certain of the more important and atypical aspects, from a corporate governance perspective, of the Council Agreement that I believe should and hopefully will create particularly significant value for Fox and its public investors for years to come. Background On Engagement 3. I was engaged in late May 2017 by co-lead counsel for Plaintiff City of Monroe Employees’ Retirement System’s (“Plaintiff”) counsel in late May 2017 to consult with respect to what was then an unfiled shareholder derivative litigation, but that I was informed had already progressed through the provision by the Plaintiff of one or more complaints 2 and had resulted in several rounds of discovery.