How Murdoch Outfoxed CBS V3.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

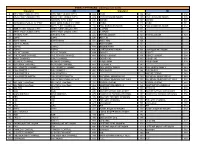

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg Interactive Channels 5145 Tropicales 225 The Weather Channel 90 Interactive Dashboard 5146 Mexicana 2 City of Las Vegas Television 230 C-SPAN 92 Interactive Games 5147 Romances 3 NBC 231 C-SPAN2 4 Clark County Television 251 TLC Digital Music Channels PrismTM Complete 5 FOX 255 Travel Channel 5101 Hit List TM 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 265 National Geographic Channel 5102 Hip Hop & R&B Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 7 Universal Sports 271 History 5103 Mix Tape 132 American Life 8 CBS 303 Disney Channel 5104 Dance/Electronica 149 G4 9 LATV 314 Nickelodeon 5105 Rap (uncensored) 153 Chiller 10 PBS 326 Cartoon Network 5106 Hip Hop Classics 157 TV One 11 V-Me 327 Boomerang 5107 Throwback Jamz 161 Sleuth 12 PBS Create 337 Sprout 5108 R&B Classics 173 GSN 13 ABC 361 Lifetime Television 5109 R&B Soul 188 BBC America 14 Mexicanal 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5110 Gospel 189 Current TV 15 Univision 364 Lifetime Real Women 5111 Reggae 195 ION 17 Telefutura 368 Oxygen 5112 Classic Rock 253 Animal Planet 18 QVC 420 QVC 5113 Retro Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 19 Home Shopping Network 422 Home Shopping Network 5114 Rock 258 Science Channel 21 My Network TV 424 ShopNBC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 25 Vegas TV 428 Jewelry Television 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 27 ESPN 451 HGTV 5117 Classic Alternative 272 Biography 28 ESPN2 453 Food Network 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 274 History International 33 CW 503 MTV 5120 Soft Rock 305 Disney XD 39 Telemundo 519 VH1 5121 Pop Hits 315 Nick Too 109 TNT 526 CMT 5122 90s 316 Nicktoons 113 TBS 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5123 80s 320 Nick Jr. -

Congressional Record—Senate S13621

November 2, 1999 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE S13621 message from the Chicago Bears. Many ex- with him. You could tell he was very The last point I will make is, toward ecutives knew what it said before they read genuine.'' the end of his life when announcing he it: Walter Payton, one of the best ever to Bears fans in Chicago felt the same way, faced this fatal illness, he made a plea which is why reaction to his death was swift play running back, had died. across America to take organ donation For the past several days it has been ru- and universal. mored that Payton had taken a turn for the ``He to me is ranked with Joe DiMaggio in seriously. He needed a liver transplant worse, so the league was braced for the news. baseballÐhe was the epitome of class,'' said at one point in his recuperation. It Still, the announcement that Payton had Hank Oettinger, a native of Chicago who was could have made a difference. It did not succumbed to bile-duct cancer at 45 rocked watching coverage of Payton's death at a bar happen. and deeply saddened the world of profes- on the city's North Side. ``The man was such I do not know the medical details as sional football. a gentleman, and he would show it on the to his passing, but Walter Payton's ``His attitude for life, you wanted to be football field.'' message in his final months is one we around him,'' said Mike Singletary, a close Several fans broke down crying yesterday as they called into Chicago television sports should take to heart as we remember friend who played with Payton from 1981 to him, not just from those fuzzy clips of 1987 on the Bears. -

Denver Broncos Roster Section 2013.Xlsx

ddenverenver bbroncosroncos 2013 weekly press release Media Relations Staff Patrick Smyth, Executive Director of Media Relations • (303-264-5536) • [email protected] Rebecca Villanueva, Media Services Manager • (303-264-5598) • [email protected] Erich Schubert, Media Relations Manager • (303-264-5503) • [email protected] 2 World Championships • 6 Super Bowls • 8 AFC Title Games • 12 AFC West Titles • 19 Playoff Berths • 26 Winning Seasons FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TUESDAY, NOV. 19, 2013 BRONCOS travel to foxborough for conference tilt with patriots Denver Broncos (9-1) at New England Patriots (7-3) Sunday, Nov. 24, 2013 • 8:30 p.m. EST Gillette Stadium (68,756) • Foxborough, Mass. GAME INFORMATION BRONCOS 2013 SCHEDULE/RESULTS After knocking off the previously unbeaten Kansas City Chiefs last week, the PRESEASON Denver Broncos (9-1) will try to stay atop the AFC standings when they travel Wk. Day Date Opponent Site Time/Result Rec. to Foxborough, Mass., to square off against the New England Patriots (7-3) 1 Thu. Aug. 8 at San Francisco Candlestick Park W, 10-6 1-0 on NBC’s Sunday Night Football. Kickoff at Gillette Stadium is scheduled for 2 Sat. Aug. 17 at Seattle CenturyLink Field L, 40-10 1-1 3 Sat. Aug. 24 ST. LOUIS Sports Authority Field at Mile High W, 27-26 2-1 8:30 p.m. EST. 4 Thu. Aug. 29 ARIZONA Sports Authority Field at Mile High L, 32-24 2-2 BROADCAST INFORMATION: REGULAR SEASON Wk. Day Date Opponent Site Time/Result TV/Rec. TELEVISION: KUSA-TV (NBC 9): Al Michaels (play-by-play) and Cris 1 Thu. -

Johnny Robinson Donates Artifacts to the Hall Momentos to Be Displayed in Special Class of 2019 Exhibit

JOHNNY ROBINSON DONATES ARTIFACTS TO THE HALL MOMENTOS TO BE DISPLAYED IN SPECIAL CLASS OF 2019 EXHIBIT June 18, 2019 - CANTON, OHIO - Class of 2019 Enshrinee JOHNNY ROBINSON recently donated several artifacts from his career and life to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Robinson starred for the Kansas City Chiefs, first known as the Dallas Texans, for 12 seasons from 1960-1971. Aligning with its important Mission to “Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE,” the Hall’s curatorial team will preserve Robinson’s artifacts for future generations of fans to see. The following are some notable items from Robinson’s collection: • Robinson’s game worn Chiefs jersey • Chiefs helmet worn by Robinson during his career • 1970 NEA-CBS All-Pro Safety Trophy awarded to Robinson after completing the season with a league-leading 10 interceptions DAYS UNTIL NFL’S 100TH SEASON KICKS OFF AT 4 4 ENSHRINEMENT WEEK POWERED BY JOHNSON CONTROLS Great seats are still available for the kickoff of the NFL’s 100th season in Canton, Ohio. Tickets and Packages for the main events of the 2019 Pro Football Hall of Fame Enshrinement Week Powered by Johnson Controls are on sale now. HALL OF FAME GAME - AUG. 1 ENSHRINEMENT CEREMONY - AUG. 3 IMAGINE DRAGONS - AUG. 4 ProFootballHOF.com/Tickets • 2018 PwC Doak Walker Legends Robinson Career Interception Statistics Award which honors former running backs who excelled at the collegiate Year Team Games Number Yards Average level and went on to distinguish 1962 Dallas 14 4 25 6.3 themselves as leaders in their 1963 Kansas City 14 3 41 13.7 communities. -

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She Overcame Her Fears and Shyness to Win Miss America 1967, Launching Her Career in Media and Government

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She overcame her fears and shyness to win Miss America 1967, launching her career in media and government Chapter 01 – 0:52 Introduction Announcer: As millions of television viewers watch Jane Jayroe crowned Miss America in 1967, and as Bert Parks serenaded her, no one would have thought she was actually a very shy and reluctant winner. Nor would they know that the tears, which flowed, were more of fright than joy. She was nineteen when her whole life was changed in an instant. Jane went on to become a well-known broadcaster, author, and public official. She worked as an anchor in TV news in Oklahoma City and Dallas, Fort Worth. Oklahoma governor, Frank Keating, appointed her to serve as his Secretary of Tourism. But her story along the way was filled with ups and downs. Listen to Jane Jayroe talk about her struggle with shyness, depression, and a failed marriage. And how she overcame it all to lead a happy and successful life, on this oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 8:30 Grandparents John Erling: My name is John Erling. Today’s date is April 3, 2014. Jane, will you state your full name, your date of birth, and your present age. Jane Jayroe: Jane Anne Jayroe-Gamble. Birthday is October 30, 1946. And I have a hard time remembering my age. JE: Why is that? JJ: I don’t know. I have to call my son, he’s better with numbers. I think I’m sixty-seven. JE: Peggy Helmerich, you know from Tulsa? JJ: I know who she is. -

Everly IPTV Channel Guide 10-7-19.Xlsx

EVERLY IPTV BASIC (continued on back) Standard HD Standard HD 4 KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) 404 CNN 104 CNN 504 9 KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) 409 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 105 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 505 KDINDT2 "IPTV KIDS" 410 MSNBC 107 MSNBC 507 11 KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" 411 CNBC 111 CNBC 511 KEYC "CBS" (MANKATO) 412 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 112 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 512 14 KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) 414 C-SPAN 115 15 KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) 415 C-SPAN2 116 22 KTIVDT2 "CW" KTIVDT2 "CW" 422 NICKELODEON 123 NICKELODEON 523 30 ESPN ESPN 430 NICK JR. 124 31 ESPN NEWS ESPN NEWS 431 NICK TOO 126 32 ESPN CLASSIC NICKTOONS 127 33 ESPNU ESPNU 433 BOOMERANG 129 35 ESPN2 ESPN2 435 CARTOON NETWORK 131 CARTOON NETWORK 531 39 NFL NETWORK NFL NETWORK 439 DISNEY 133 DISNEY 533 43 THE TENNIS CHANNEL THE TENNIS CHANNEL 443 DISNEY JUNIOR 134 DISNEY JUNIOR 534 44 GOLF CHANNEL GOLF CHANNEL 444 DISNEY XD 136 DISNEY XD 536 45 OLYMPIC CHANNEL OLYMPIC CHANNEL 445 FREEFORM 138 FREEFORM 538 47 OUTDOOR CHANNEL OUTDOOR CHANNEL 447 TEEN NICK 140 49 NBC SPORTS CHANNEL NBC SPORTS CHANNEL 449 DISCOVERY FAMILY 143 DISCOVERY FAMILY 543 50 FOX SPORTS 1 FOX SPORTS 1 450 DISCOVERY 144 DISCOVERY 544 51 FOX SPORTS 2 FOX SPORTS 2 451 MOTOR TREND 545 55 FOX SPORTS NORTH FOX SPORTS NORTH 455 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 149 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 549 FOX SPORTS NORTH PLUS 457 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 150 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 550 61 BIG TEN 1 (overflow) BIG TEN 1 (overflow) 461 ANIMAL PLANET 153 -

March 31 ACMA Eye Pa

8 March 31 - April 1, 2012 The Weekend Australian Financial Review www.afr.com News Pay TV piracy From `big problem' to `fixable' Porter changes view on severity Austar Key points Angus Grigg @ John Porter and Kim Williams lobbied to make pay TV piracy a specific criminal offence. Austar chief executive John Porter conceded on Friday piracy in the @ On Friday, Mr Porter said such pay TV industry was a major issue piracy was `not an endemic and may have cost his company long-term problem'. up to $17 million in some years. ªYeah, look, it is a big number,º Cottle as a threat to any NDS he told the Weekend Financial systems but without disturbing his Review. ªI acknowledge that piracy other hacking activities (as much was a significant problem but as possible),º Ms Gutman wrote. there is always a fix.º ªWe do not want Cottle in jail Mr Porter's comments come until he has a successor for the after The Australian Financial Irdeto hack.º Review published a series of Austar was one of Irdeto's main articles during the week detailing clients in Australia. Mr Porter how a News Corp subsidiary, NDS, would not comment on the email promoted a global wave of pay TV except to say: ªAvigail what's-her- piracy in the late 1990s. name was maybe a little too Austar and its smartcard excitable.º provider, Irdeto, were two of NDS's He also argued that it was in main targets. ªnobody's interestº to have the On Friday, Austar shareholders Irdeto platform hacked, as it had voted in favour of a takeover by also provided services to Foxtel's Foxtel, cementing its dominance satellite customers. -

"The Olympics Don't Take American Express"

“…..and the Olympics didn’t take American Express” Chapter One: How ‘Bout Those Cowboys I inherited a predisposition for pain from my father, Ron, a born and raised Buffalonian with a self- mutilating love for the Buffalo Bills. As a young boy, he kept scrap books of the All American Football Conference’s original Bills franchise. In the 1950s, when the AAFC became the National Football League and took only the Cleveland Browns, San Francisco 49ers, and Baltimore Colts with it, my father held out for his team. In 1959, when my father moved the family across the country to San Jose, California, Ralph Wilson restarted the franchise and brought Bills’ fans dreams to life. In 1960, during the Bills’ inaugural season, my father resumed his role as diehard fan, and I joined the ranks. It’s all my father’s fault. My father was the one who tapped his childhood buddy Larry Felser, a writer for the Buffalo Evening News, for tickets. My father was the one who took me to Frank Youell Field every year to watch the Bills play the Oakland Raiders, compliments of Larry. By the time I had celebrated Cookie Gilcrest’s yardage gains, cheered Joe Ferguson’s arm, marveled over a kid called Juice, adapted to Jim Kelly’s K-Gun offense, got shocked by Thurman Thomas’ receptions, felt the thrill of victory with Kemp and Golden Wheels Dubenion, and suffered the agony of defeat through four straight Super Bowls, I was a diehard Bills fan. Along with an entourage of up to 30 family and friends, I witnessed every Super Bowl loss. -

Channel Lineup January 2018

MyTV CHANNEL LINEUP JANUARY 2018 ON ON ON SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND My64 (WSTR) Cincinnati 11 511 Foundation Pack Kids & Family Music Choice 300-349• 4 • 4 A&E 36 536 4 Music Choice Play 577 Boomerang 284 4 ABC (WCPO) Cincinnati 9 509 4 National Geographic 43 543 4 Cartoon Network 46 546 • 4 Big Ten Network 206 606 NBC (WLWT) Cincinnati 5 505 4 Discovery Family 48 548 4 Beauty iQ 637 Newsy 508 Disney 49 549 • 4 Big Ten Overflow Network 207 NKU 818+ Disney Jr. 50 550 + • 4 Boone County 831 PBS Dayton/Community Access 16 Disney XD 282 682 • 4 Bounce TV 258 QVC 15 515 Nickelodeon 45 545 • 4 Campbell County 805-807, 810-812+ QVC2 244• Nick Jr. 286 686 4 • CBS (WKRC) Cincinnati 12 512 SonLife 265• Nicktoons 285 • 4 Cincinnati 800-804, 860 Sundance TV 227• 627 Teen Nick 287 • 4 COZI TV 290 TBNK 815-817, 819-821+ TV Land 35 535 • 4 C-Span 21 The CW 17 517 Universal Kids 283 C-Span 2 22 The Lebanon Channel/WKET2 6 Movies & Series DayStar 262• The Word Network 263• 4 Discovery Channel 32 532 THIS TV 259• MGM HD 628 ESPN 28 528 4 TLC 57 557 4 STARZEncore 482 4 ESPN2 29 529 Travel Channel 59 559 4 STARZEncore Action 497 4 EVINE Live 245• Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) 18 STARZEncore Action West 499 4 EVINE Too 246• Velocity HD 656 4 STARZEncore Black 494 4 EWTN 264•/97 Waycross 850-855+ STARZEncore Black West 496 4 FidoTV 688 WCET (PBS) Cincinnati 13 513 STARZEncore Classic 488 4 Florence 822+ WKET/Community Access 96 596 4 4 STARZEncore Classic West 490 Food Network 62 562 WKET1 294• 4 4 STARZEncore Suspense 491 FOX (WXIX) Cincinnati 3 503 WKET2 295• STARZEncore Suspense West 493 4 FOX Business Network 269• 669 WPTO (PBS) Oxford 14 STARZEncore Family 479 4 FOX News 66 566 Z Living 636 STARZEncore West 483 4 FOX Sports 1 25 525 STARZEncore Westerns 485 4 FOX Sports 2 219• 619 Variety STARZEncore Westerns West 487 4 FOX Sports Ohio (FSN) 27 527 4 AMC 33 533 FLiX 432 4 FOX Sports Ohio Alt Feed 601 4 Animal Planet 44 544 Showtime 434 435 4 Ft. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES and QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ Is One of Eight Members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019

TONY GONZALEZ FACT SHEET BIOS, RECORDS, QUICK FACTS, NOTES AND QUOTES TONY GONZALEZ is one of eight members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Class of 2019. CAPSULE BIO 17 seasons, 270 games … First-round pick (13th player overall) by Chiefs in 1997 … Named Chiefs’ rookie of the year after recording 33 catches for 368 yards and 2 TDs, 1997 … Recorded more than 50 receptions in a season in each of his last 16 years (second most all-time) including 14 seasons with 70 or more catches … Led NFL in receiving with career-best 102 receptions, 2004 … Led Chiefs in receiving eight times … Traded to Atlanta in 2009 … Led Falcons in receiving, 2012… Set Chiefs record with 26 games with 100 or more receiving yards; added five more 100-yard efforts with Falcons … Ranks behind only Jerry Rice in career receptions … Career statistics: 1,325 receptions for 15,127 yards, 111 TDs … Streak of 211 straight games with a catch, 2000-2013 (longest ever by tight end, second longest in NFL history at time of retirement) … Career-long 73- yard TD catch vs. division rival Raiders, Nov. 28, 1999 …Team leader that helped Chiefs and Falcons to two division titles each … Started at tight end for Falcons in 2012 NFC Championship Game, had 8 catches for 78 yards and 1 TD … Named First-Team All- Pro seven times (1999-2003, TIGHT END 2008, 2012) … Voted to 14 Pro Bowls … Named Team MVP by Chiefs 1997-2008 KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (2008) and Falcons (2009) … Selected to the NFL’s All-Decade Team of 2009-2013 ATLANTA FALCONS 2000s … Born Feb. -

N E W S L E T T

A publication of July 2019 NEWSACTIONLETTER MEET STARK’S FUTURE LEADERS ON PAGE 20! LEADERSHIP STARK COUNTY GRADUATES FIRST YOUTH LEADERSHIP ACADEMY CLASS! ENSHRINEMENT FESTIVAL CANTON FARMERS’ MARKET GOLF PAR-TEE Heats up in July & August Through Sept. 28 August 23 ACTION 7TH Annual UTICA SUMMIT NEWSLETTER SET FOR OCTOBER 10 - SAVE THE DATE! JULY 2019 DOWNSTREAM DEVELOPMENT: ETHANE CRACKER PLANT Vol. III • Issue III UPDATES, POLYMER UPDATES, AND MORE! Utica Summit is our annual look at the sustainable downstream benefits of Utica energy. National speakers come here to tell you what’s coming our way. The Canton Regional Chamber of Commerce and ShaleDirectories.com have partnered Rick McQueen to produce another conference designed to give insight on energy in Utica and beyond. Chairman We know the coming downstream build out is going to be much bigger than many Retired of us can imagine. Hear from experts: Dennis P. Saunier President & CEO • Petrochemicals | Appalachian Basin, Joe Barone, President Shale Directories Steven M. Meeks • Shell and PTTGC Cracker Plant Updates | Tom Gellrich, TopLine Analytics Chief Operating Officer Collyn Floyd • Plastics Industry Outlook and Panel | Perc Pineda, Chief Economist, Plastics Editor and Industry Association Director of Marketing Molly Romig • NEO Outlook | Dr. Iryna Lendel, Research Associate Professor and Advertising Sales / Action Director of the Center for Economic Development, Cleveland State 330.833.4400 University Sarah Lutz Graphics Manager • Plastics Packaging Recycling 100% by 2030? | American Chemistry Council For registration and questions, go online to UticaSummit.com or contact Melissa Elsfelder at 330- 458-2073 or [email protected]. For sponsorship opportunities, ACTION NEWSLETTER (USPS 989-440) is contact Chris Gumpp at 330-458-2055 or [email protected].