Social Engineering and the Social Sciences in China, 1919-1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for 1950S China-India History

Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghosh, Arunabh. 2017. Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History. The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3: 697-727. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41288160 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP DRAFT: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History Arunabh Ghosh ABSTRACT China-India history of the 1950s remains mired in concerns related to border demarcations and a teleological focus on the causes, course, and consequence of the war of 1962. The result is an overt emphasis on diplomatic and international history of a rather narrow form. In critiquing this narrowness, this paper offers an alternate chronology accompanied by two substantive case studies. Taken together, they demonstrate that an approach that takes seriously cultural, scientific and economic life leads to different sources and different historical arguments from an approach focused on political (and especially high political) life. Such a shift in emphasis, away from conflict, and onto moments of contact, comparison, cooperation, and competition, can contribute fresh perspectives not just on the histories of China and India, but also on histories of the Global South. Arunabh Ghosh ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese History in the Department of History at Harvard University Vikram Seth first learned about the death of “Lita” in the Chinese city of Turfan on a sultry July day in 1981. -

Asian Social Science, ISSN 1911-2017, Vol. 4, No. 1, January

Vol. 4, No. 1 Asian Social Science January 2008 www.ccsenet.org/journal.html Contents The Roles of Teachers in Implementing Educational Innovation: The Case of 3 Implementing Cooperative Learning in Vietnam Pham Thi Hong Thanh An Analyses of Yuan Shikai’s Policy towards Japan 10 Deren Lin & Haixiao Yan A Brief Analysis on Elite Democracy in Authoritarianism Countries 13 Jia Hong Learning English as a Foreign Language: Cultural Values and Strategies in the Chinese Context 18 Yunbao Yang On the Objective System of Modern Peasant Household Cultivation Strategy 23 Zhucun Zhao Supervisory Framework of China Electric Power Universal Service 26 Guoliang Luo & Zhiliang Liu Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Perspectives on Organizational Management 30 Balakrishnan Muniapan The Psychology of Western Independent Tourists and Its Impacts on Chinese Tourism Management 35 Li Song Developing Students’ Oral Communicative Competence through Interactive Learning 43 Baohua Guo Developing Organizations through Developing Individuals: Malaysian Case Study 51 Mohamad Hisyam Selamat, Muhammad Syahir Abd. Wahab, Mohd. Amir Mat Samsudin Discussion on the Sustainable Development of Electric Power Industry in China 63 Shijun Yang, Dongxiao Niu, Yongli Wang An Empirical Study on IPO Underpricing Under Full Circulation in China 67 Pingzhen Li Is Full Inclusion Desirable? 72 Melissa Brisendine, David Lentjes, Cortney Morgan, Melissa Purdy, Will Wagnon Chris Woods, Larry Beard, Charles E. Notar An Empirical Research on the Relations between Higher Education Development and 78 Economic Growth in China Xiaohong Wang & Shufen Wang On Party Newspaper’s Dominant Role and Its Marginalization in Operating 83 Xiangyu Chen HIV/AIDS in Vietnam: A Gender Analysis 89 Nguyen Van Huy & Udoy Sankar Saikia Asian Social Science Vol. -

The Chinese Commission to Cuba (1874): Reexamining International Relations in the Nineteenth Century from a Transcultural Perspective

Transcultural Studies 2014.2 39 The Chinese Commission to Cuba (1874): Reexamining International Relations in the Nineteenth Century from a Transcultural Perspective Rudolph Ng, St Catharine’s College Cambridge Fig. 1: Cover page of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June 1864, Vol. 29. (Cornell University Library) doi: 10.11588/ts.2014.2.13009 40 The Chinese Commission to Cuba (1874) As the abolitionist movement gained momentum in the second half of the nineteenth century, agricultural producers in Cuba and South America urgently began looking for substitutes for their African slaves. The result was a massive growth in the “coolie trade”––the trafficking of laborers known as coolies––from China to plantations overseas.1 On paper, the indentured workers were abroad legally and voluntarily and were given regular salaries, certain benefits, as well as various legal rights not granted to slaves. In practice, however, coolies were often kidnapped before departure and abused upon arrival. Their relatively low wages and theoretically legal status attracted employers in agricultural production around the world. Virtually all the European colonies employed coolies; from the Spanish sugar plantations in Cuba to the German coconut fields in Samoa, coolies were a critical source of labor. For the trade in coolies between China and Latin America, a handful of Spanish conglomerates, such as La Zulueta y Compañía and La Alianza, held the monopoly. Assisted by Spanish diplomatic outposts, these conglomerates established coolie stations along the south Chinese coast to facilitate the transportation of laborers. Their branches across the globe handled the logistics, marketing, and finances of the trade. The substantial profits accrued from the high demand for labor encouraged the gradual expansion of the trade after 1847, with the highest number of coolies being shipped to Cuba and Peru in the 1860s and 1870s. -

China's Smiling Face to the World: Beijing's English

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Leonard W. Lazarick, M.A. History Directed By: Professor James Z. Gao Department of History In the 1950s, the People’s Republic of China produced several English-language magazines to inform the outside world of the remarkable transformation of newly reunified China into a modern and communist state: People’s China, begun in January 1950; China Reconstructs, starting in January 1952; and in March 1958, Peking Review replaced People’s China. The magazines were produced by small staffs of Western- educated Chinese and a few experienced foreign journalists. The first two magazines in particular were designed to show the happy, smiling face of a new and better China to an audience of foreign sympathizers, journalists, academics and officials who had little other information about the country after most Western journalists and diplomats had been expelled. This thesis describes how the magazines were organized, discusses key staff members, and analyzes the significance of their coverage of social and cultural issues in the crucial early years of the People’s Republic. CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC By Leonard W. Lazarick Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor James Z. Gao, Chair Professor Andrea Goldman Professor Lisa R. -

The Internal and External Competition and System Changes Under the Background of Modern Chinese Party Politics

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 16, No. 11, 2020, pp. 11-16 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/11940 www.cscanada.org The Internal and External Competition and System Changes Under the Background of Modern Chinese Party Politics ZENG Rong[a]; LIU Yanhan[b]; ZENG Qinhan[c],* [a]Professor, School of Marxism, Guangdong University of Foreign Zeng, R., Liu, Y. H., & Zeng, Q. H. (2020). The Internal and External Studies, Guangzhou, China. Competition and System Changes Under the Background of Modern [b]Researcher, School of Marxism, Guangdong University of Foreign Chinese Party Politics. Canadian Social Science, 16(11), 11-16. Available Studies, Guangzhou, China. from: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/css/article/view/11940 [c] Researcher, Library, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/11940 Guangzhou, China. *Corresponding author. Supported by the China National Social Science Fund Project “Yan’an Cultural Association and the Construction of Marxist Discourse INTRODUCTION Power” (Project Number: 2019BDJ032); The 13th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Guangzhou The rise of Chinese party politics began in the late Qing “Guangzhou Communist Group and the Construction of Marxist Dynasty and the early Republic of China. Liang Qichao, Discourse Power” (Project Number: 2020GZYB51). Ma Xiangbo, Yang Du and others imitated the Western political system to advocate party politics in China, Received 11 August 2020; accepted 7 October 2020 Published online 26 November 2020 which strongly promoted the historical process of China’s political democratization and diplomatic democratization. In response to the current situation of China’s domestic Abstract and foreign troubles, the people’s requirements for Since modern times, Chinese intellectual Liang Qichao participating in the country’s political and foreign affairs and others have imitated the Western political system by organizing political parties have been increasing. -

49, 219, 224 12Th Army 42, 43, 129, 134, 177 51St Corps 43, 108

INDEX “3-3 system” 49, 219, 224 178, 180, 190–191, 194–196, 12th Army 42, 43, 129, 134, 177 198–199, 202–203, 214–215, 217, 51st Corps 43, 108, 110, 125, 129, 131 221, 231–232, 244–245 57th Corps 35, 43, 125, 130–131 Bohai 5–6, 21, 63, 108, 161, 195, 89th Corps 43 231–232 92nd Corps 142 Britain xxvi, xxvii, 97, 104, 110, 117, 111th Division 130, 139–141 122, 218, 235 115th Division 22–23, 27, 33–39, 44, Budget xxvi, xxx, 4, 33, 51, 53, 56, 46–4 64–66, 69–71, 99, 138, 146, 150, 191, 203–204, 223 Agrarian revolution xxxiii, 155, 207, Bureau of Industry and Commerce 227, 238–240 See: BIC Ai Chunan 67, 94–95, 141, 157, 243 Aiguo gongliang 83 (See: Grain Cai Jinkang 26, 58, 60, 82, 107–108, requisition) 244 Anhui 9, 18, 27–28, 35, 37, 40, Canshi zhengche See: “Silkworm-eating 42, 46, 48, 65, 67, 104–106, 125, strategy” 135–136, 142–143, 161–163, Cao Manzhi 20 168–169, 171, 230 CCP See: Chinese Communist Party Anti-surrender Campaign 106 Central China Bureau 104, 118, 222, 230, 237 Baiyan 48–49 Central Military Commission 54, Bank of South Hebei 61 117–119 Baodugu 17, 47–48, 63 Central Secretariat 36–37, 53–55, 118, Baojia 32, 134, 179 121, 138, 209–210 “Barehanded soldiers” 46 Chang Enduo 130, 139 Battle of Huangqiao 104–105, 209 Changyi 20, 179, 245 Battle of the Hundred Regiments 104 Chen Guang 39, 113, 118–120, 131, Battle of the Philippine Sea 200, 222, 140–142 227 Chen Hansheng 151–155 Beihai yinhang See: North Sea Bank Chen Yi 237 Beijing 1, 7, 79, 135 Chen Yun-fa xix Beipiao Chiang Kai-shek Beginning xv, xvi, xxxi, 24–26, 58 Decision -

The Transition of the Kuomintang Government's Policies Towards

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.20 No.2, Aug. 2015) 153 a 1946: The Transition of the Kuomintang Government’s Policies towards Korean Immigrants in Northeast China* Zhang Muyun** Introduction Currently, the research on the Kuomintang Government’s policies to- wards Korean immigrants has gradually increased. Scholars have attached great importance to the use of archival resources in Shanghai, Tianjin, Peking, Wuhan and Liaoning. Yang Xiaowen1 (2008) made use of the original records to discuss post-war China’s policies towards the repatria- tion of Korean immigrants in the Wuhan area. Ma Jun, Shan Guanchu2 (2006) adequately utilized Zhongguo diyu hanren tuanti guanxi shiliao * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 3rd Annual Korea University Korean History Graduate Student Conference, 2015, Korea University. I thank my discussant and conference participants for valuable discussions. I also appreciate the IJKH reviewers for very helpful comments. ** MA student, Major in history of modern China, School of Marxism, Tsinghua University. 1 Yang Xiaowen. “Zhanhou zhongguo guannei hanren de jizhong qianfan zhengce ji qi shijian yanjiu: yi wuhan wei gean fenxi” (the post-war Chinese’s policies to- wards repatriation of Korean immigrants in Wuhan area) (Master diss., Fudan University, 2008). 2 Ma Jun, Shan Guanchu. “Zhanhou guomin zhengfu qianfan hanren zhengce de yanbian ji zai shanghai diqu de shijian” (the development of the Kuomintang gov- ernment’s policies towards repatriation of Korean immigrants in Shanghai area), Shilin, 2006(2). 154 1946: The Transition of the Kuomintang Government’s Policies ~ huibian3(the Comprehensive Collection of Archival Papers on Korean immigrants’ organizations in China) to investigate the development of the Kuomintang government’s policies towards the repatriation of Korean immigrants in the Shanghai area. -

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Yurou Zhong All rights reserved ABSTRACT Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Yurou Zhong This dissertation examines the modern Chinese script crisis in twentieth-century China. It situates the Chinese script crisis within the modern phenomenon of phonocentrism – the systematic privileging of speech over writing. It depicts the Chinese experience as an integral part of a worldwide crisis of non-alphabetic scripts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It places the crisis of Chinese characters at the center of the making of modern Chinese language, literature, and culture. It investigates how the script crisis and the ensuing script revolution intersect with significant historical processes such as the Chinese engagement in the two World Wars, national and international education movements, the Communist revolution, and national salvation. Since the late nineteenth century, the Chinese writing system began to be targeted as the roadblock to literacy, science and democracy. Chinese and foreign scholars took the abolition of Chinese script to be the condition of modernity. A script revolution was launched as the Chinese response to the script crisis. This dissertation traces the beginning of the crisis to 1916, when Chao Yuen Ren published his English article “The Problem of the Chinese Language,” sweeping away all theoretical oppositions to alphabetizing the Chinese script. This was followed by two major movements dedicated to the task of eradicating Chinese characters: First, the Chinese Romanization Movement spearheaded by a group of Chinese and international scholars which was quickly endorsed by the Guomingdang (GMD) Nationalist government in the 1920s; Second, the dissident Chinese Latinization Movement initiated in the Soviet Union and championed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1930s. -

WWI & Japan's Twenty-One Demands

First World War & China - Japan's Twenty-one Demands by Ah Xiang Excerpts from “Tragedy of Chinese Revolution” at http://www.republicanchina.org/revolution.html For updates and related articles, check http://www.republicanchina.org/RepublicanChina-pdf.htm Tang Degang pointed out that Russia and Japan signed three secret treaties, with such clauses as dividing Manchuria & Mongolia should China's revolution lead to national instability. Fortunately, 1911 Xin Hai Revolution ended in a matter of less than 3 months, while Second Revolution was even shorter in duration. WWI broke out on July 28th 1914. On Aug 15th 1914, Japan issued an ultimatum to Germany as to ceding Jiaozhou-wan Bay to Japan management and Chinese sovereignty by Sept 15th 1914. Jiaozhou-wan Bay was first leased to Germany for 99 years on March 6th 1898 in the aftermath of death of two German missionaries. Before one month ultimatum was to expire, Japan, on Aug 23rd 1914, attacked the German interests in China. Twenty thousand Japanese soldiers landed in Longkou, and then attacked Qingdao. Yuan Shikai, to maintain neutrality, had to carve out an area for the two parties to fight. Though China designated the area to the east of Weixian county train station, Japanese, having declined German request for handover of leased territory to China, would go west to occupy the Jiao-Ji [Qingdao-Jinan] Railway on the pretext that the railway was a Sino-German venture. On Oct 6th, Japanese took over Jinan train station, arrested German staff, and expelled Chinese staff. Reinsch, i.e., American legation envoy who arrived in China in the wake of President Yuan Shi-kai's expulsion of KMT from the Parliament in 1913, "warned Washington of Japan's menacing ambitions when the Japanese army seized the German areas of influence in China, in Shandong Province" per Mike Billington. -

Chapter 2 from Mass Campaigns to Managed Campaigns: “Constructing a New Socialist Countryside” Elizabeth J

chapter 2 From Mass Campaigns to Managed Campaigns: “Constructing a New Socialist Countryside” Elizabeth J. Perry Campaigns: A Relic of the Revolutionary Past? It is often said that one of the most important differences between the Mao and post-Mao eras is the replacement of “revolutionary” campaigns by “rational” bureaucratic modes of governance. With the death of Mao Zedong and the gradual but steady substitution among the political leader- ship of younger engineers for elderly revolutionaries, China appeared to have settled into post-revolutionary technocratic rule. Hung Yung Lee wrote in 1991, “[D]uring the Mao era the regime’s primary task — socialist revolu- tion — reinforced its leadership method of mass mobilization and its com- mitment to revolutionary change .... [T]he replacement of revolutionary cadres by bureaucratic technocrats signifies an end to the revolutionary era in modern China.”1 A decade later, Cheng Li’s study of the current generation of Chinese leaders reaches a similar conclusion, observing that “the technocratic orientation in the reform era certainly departs from the Mao era, when the Chinese Communist regime was preoccupied with con- stant political campaigns and ‘mass line’ politics.”2 This assertion that revo- lutionary campaigns have given way to rational-bureaucratic administration fits comfortably with comparative communism variants of modernization theory, in which the inexorable ascendance of “experts” over “reds” as a result of industrialization ensures that radical utopianism will give way to a less ambitious “post-revolutionary phase.”3 Most China scholars (and surely most Chinese citizens) welcomed Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 declaration that the campaign era had ended. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Song Zheyuan, the Nanjing government and the north china question in Sino-Japanese relations, 1935-1937 Dryburgh, Marjorie E. How to cite: Dryburgh, Marjorie E. (1993) Song Zheyuan, the Nanjing government and the north china question in Sino-Japanese relations, 1935-1937, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5777/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Song Zheyuan, the Nanjing Government and the North China Question in Sino-Japanese Relations, 1935-1937. Abstract The focus of this study is the relationship between the Chinese central government and Song Zheyuan, the key provincial leader of North China, in the period immediately preceding the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the impact of tensions in that relationship on Japan policy. The most urgent task confronting the Chinese government in the late 1930s was to secure an equitable and formally-negotiated settlement of outstanding questions with the Tokyo government. -

Introduction

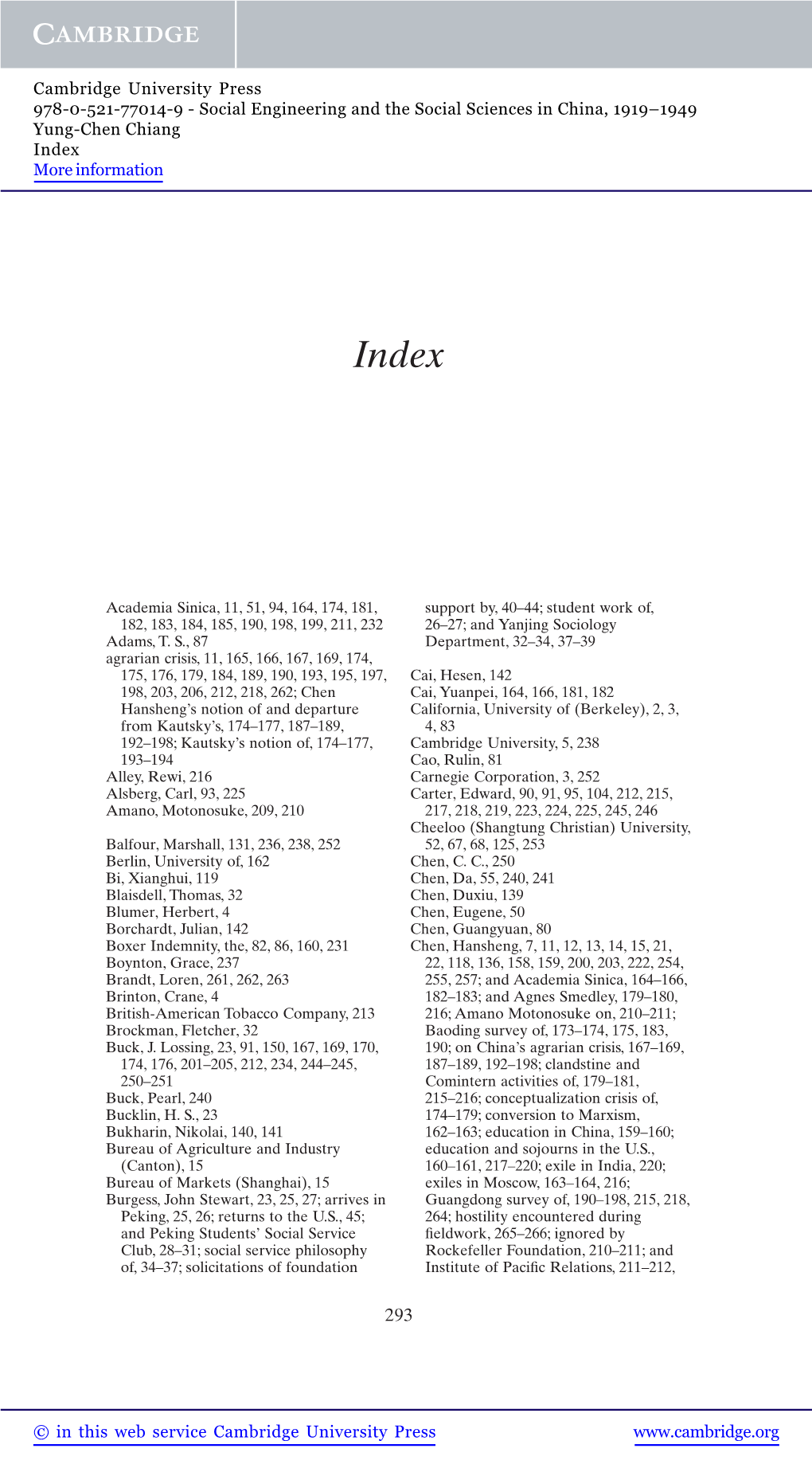

Cambridge University Press 0521027241 - Social Engineering and the Social Sciences in China, 1919-1949 Yung-chen Chiang Excerpt More information 1 Introduction When it comes to learning, sociology is the foundation. Only when sociology is understood will the cause of peace or dis- order, prosperity or decline, be known, and will objectives from self-cultivation, ordering one’s family, pacifying a nation, to bringing peace to the world be achieved.Truly this is a great learning! Yan Fu (1896)1 ocial science research in China during the 1930s constituted part of Sa larger phenomenon that occurred simultaneously in the United States and Western Europe. It was a movement toward an empirical study of society in order to control the social, political, and economic forces at work. The origins of this social science movement are diverse due to the differences in the academic and cultural traditions of these countries.2 However, when the movement came to represent a new approach in the early twentieth century, it exhibited not only a strikingly uniform tendency toward empirical research, but a belief in the techno- cratic potentials of the social sciences.3 1. Yan Fu, “Yuan qiang” (On Strength), Yan Fu sixiang zhitan (Themes of Yan Fu’s Thought) (Hong Kong, 1980), p. 16. 2. For a bird’s-eye view of this phenomenon, especially in connection with sociology, see Martin Bulmer, Kevin Bales, and Kathryn Kish Sklar, eds., The Social Survey in Historical Perspective, 1880–1940 (Cambridge, 1991) and Edward Shils, The Calling of Sociology and Other Essays on the Pursuit of Learning (Chicago, 1980), especially “The Confluence of Sociological Traditions,” pp.