Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation Between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong,” February 04, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, APRF: F. 39, Op. 1, D. 39, Ll. 54-62. Reprinted in Andrei Ledovskii, Raisa Mirovitskaia and Vladimir Miasnikov, Sovetsko-Kitaiskie Otnosheniia, Vol. 5, Book 2, 1946-February 1950 (Moscow: Pamiatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2005), pp. 66-72. Translated by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113318 Summary: Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong discuss the independence of Mongolia, the independence movement in Xinjiang, the construction of a railroad in Xinjiang, CCP contacts with the VKP(b), the candidate for Chinese ambassador to the USSR, aid from the USSR to China, CCP negotiations with the Guomindang, the preparatory commisssion for convening the PCM, the character of future rule in China, Chinese treaties with foreign powers, and the Sino-Soviet treaty. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation On 4 February 1949 another meeting with Mao Zedong took place in the presence of CCP CC Politburo members Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Ren Bishi, Zhu De and the interpreter Shi Zhe. From our side Kovalev I[van]. V. and Kovalev E.F. were present. THE NATIONAL QUESTION I conveyed to Mao Zedong that our CC does not advise the Chinese Com[munist] Party to go overboard in the national question by means of providing independence to national minorities and thereby reducing the territory of the Chinese state in connection with the communists' take-over of power. -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

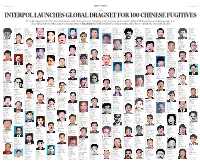

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

20 JOMSA Only Foreign Head of State to Receive the Award Was the Taisho Emperor of Japan

(“Grand Merit Order”) instead of Da Bao Zhang (“Grand President Yuan on the anniversary of the Wuchang Precious Order”). Uprising but declined by Sun The sash for the sash badge (Figure 8) was Imperial • Li Yuanhong – awarded October 10, 1912 by President Yuan to Vice President Li on the anniversary of the yellow) and was worn over the left shoulder.21 The Wuchang Uprising insignia was to be worn on formal dress although it could also be worn with informal attire where required • The Taisho Emperor of Japan – awarded November for diplomacy.22 10, 1915 by President Yuan • Feng Guozhang (Figure 9) – awarded July 6, 1917 by President Li Yuanhong to Vice President Feng • Xu Shichang (Figure 10) – awarded October 10, 1918 by President Xu Shichang to himself on the anniversary of the Wuchang Uprising • Duan Qirui – awarded September 15, 1919 by President Xu Shichang to Premier Duan Qirui • Cao Kun (Figure 11)– awarded October 10, 1923 by President Cao Kun to himself on the anniversary of the Wuchang Uprising • Zhang Zuolin – awarded around 1927 by Zhang Zuolin to himself as Grand Marshal of China24 Seven were presidents (or equivalent, in the case of Zhang Zuolin). Notwithstanding the 1912 Decree, the Grand Order was also awarded to vice-presidents and premiers Figure 8: Illustration of the Republican Grand Order sash badge reverse with the name of the Order (Da Xun Zhang, 大勋章) in seal script. Compare the characters to that of the Imperial Grand Order in Figure 5 (www.gmic.co.uk). The regulations provided for the surrender or return of the insignia upon the death of the recipient, or upon conviction of criminal or other offences.23 Given the chaotic times of the early Republic, this did not necessarily occur in practice. -

1 Reexaminating TERAUCHI Masatake's Character

February 2019 Issue Reexaminating TERAUCHI Masatake's Character - As a “Statesman”- KANNO Naoki, Cheif, Military Archives, Center for Military History Introduction What comes to mind when you think of TERAUCHI Masatake (1852 - 1919)? For example, at the beginning of the Terauchi Cabinet (October 1616 - September 1918), it was ridiculed as being both anachronistic and a non-constitutional cabinet. Using NISHIHARA Kamezo, also known as Terauchi's private secretary, he provided funds of up to 110 million yen to the Duan Qirui government in northern China (the Nishihara Loans). The so-called Rice Riots broke out in his final year, and Siberian Intervention began. Terauchi was also called a protégé of YAMAGATA Aritomo, the leading authority on Army soldiers from former Choshu domain (Choshu-han). On the other hand, what about the succeeding Hara Cabinet (September 1918 - November 1921)? Exactly 100 years ago, HARA Takashi had already started the cabinet that consists of all political party members, except for the three Ministers of the Army, Navy, and Foreign Affairs. After the World War I, a full-on party politics was developed in Japan as global diplomatic trends drastically changed. Compared to Hara, Terauchi has not been evaluated. After Chinese-Japanese relations deteriorated following the Twenty-One Demands in 1915, the aforementioned Nishihara Loans, implemented for recovery, were over-extended to the only northern part of China, the Duan Qirui government only for a limited time. Then, ultimately, the Loans did not lead an improvement in relationships. Thus it can be said that, until recently, Terauchi's character has been almost entirely neglected by academia. -

General He Yingqin: the Rise and Fall of Nationalist China. <I>By Peter Worthing</I>

Pacific Affairs: Volume 90, No. 3 – September 2017 The chapters that frame this volume make clear the different approaches that China and the United States have towards energy security. Ideologically, US and Chinese pursuit of energy security reflect radically differing embedded assumptions. As the authors note, while the US has long advocated markets over mercantilism and institutions that help avoid zero-sum approaches in crisis, China has emphasized securing external supply and developing long- term state-to-state relationships. The cases presented here suggest that the US has not used energy to constrain China’s rise, but neither has it focused on safeguarding the US market vision for energy. This volume strongly illustrates China’s long-term commitment to ensuring its access to adequate energy for the future. Meanwhile, the United States, through the development of its resources at home (and radical shifts in price), has become less engaged in energy development and in the concerns of resource-rich states. How China’s participation will change markets and relations in the long term remains to be seen, but this volume offers rare insight into how China’s participation is progressing to date. National War College/National Defense University Theresa Sabonis-Helf Washington, DC, USA *Views expressed in this review are solely the author’s and do not represent the official position of the US Government, Department of Defense, or the National Defense University. GENERAL HE YINGQIN: The Rise and Fall of Nationalist China. By Peter Worthing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. viii, 316 pp. (Maps.) US$99.99, cloth. ISBN 978-1-107-14463-7. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hobsbawm 1990, 66. 2. Diamond 1998, 322–33. 3. Fairbank 1992, 44–45. 4. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1–2. 5. Diamond 1998, 323, original emphasis. 6. Crossley 1999; Di Cosmo 1998; Purdue 2005a; Lavely and Wong 1998, 717. 7. Richards 2003, 112–47; Lattimore 1937; Pan Chia-lin and Taeuber 1952. 8. My usage of the term “geo-body” follows Thongchai 1994. 9. B. Anderson 1991, 86. 10. Purdue 2001, 304. 11. Dreyer 2006, 279–80; Fei Xiaotong 1981, 23–25. 12. Jiang Ping 1994, 16. 13. Morris-Suzuki 1998, 4; Duara 2003; Handler 1988, 6–9. 14. Duara 1995; Duara 2003. 15. Turner 1962, 3. 16. Adelman and Aron 1999, 816. 17. M. Anderson 1996, 4, Anderson’s italics. 18. Fitzgerald 1996a: 136. 19. Ibid., 107. 20. Tsu Jing 2005. 21. R. Wong 2006, 95. 22. Chatterjee (1986) was the first to theorize colonial nationalism as a “derivative discourse” of Western Orientalism. 23. Gladney 1994, 92–95; Harrell 1995a; Schein 2000. 24. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1. 25. Cohen 1991, 114–25; Schwarcz 1986; Tu Wei-ming 1994. 26. Harrison 2000, 240–43, 83–85; Harrison 2001. 27. Harrison 2000, 83–85; Cohen 1991, 126. 186 • Notes 28. Duara 2003, 9–40. 29. See, for example, Lattimore 1940 and 1962; Forbes 1986; Goldstein 1989; Benson 1990; Lipman 1998; Millward 1998; Purdue 2005a; Mitter 2000; Atwood 2002; Tighe 2005; Reardon-Anderson 2005; Giersch 2006; Crossley, Siu, and Sutton 2006; Gladney 1991, 1994, and 1996; Harrell 1995a and 2001; Brown 1996 and 2004; Cheung Siu-woo 1995 and 2003; Schein 2000; Kulp 2000; Bulag 2002 and 2006; Rossabi 2004. -

1 EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor

EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor of History and International Affairs The George Washington University CONTACT INFORMATION Office: 1957 E Street, NW, Suite 503 Sigur Center for Asian Studies The George Washington University Washington, D.C. 20052 Phone: 202-994-5785 Fax: 202-994-6096 Home: 807 Philadelphia Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20910 Phone: 301-588-6948 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Michigan, History, 1985 M.A. University of Michigan, History, 1978 B.A. Summa Cum Laude, Marian College, History, 1973 OVERSEAS STUDY AND RESEARCH 1992-1993 Research, People's Republic of China Summer 1992 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan 1981-1983 Dissertation Research, People's Republic of China 1975-1977 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor of History and International Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2015 to present (Associatte Professor of History and International Affairs, September 1994 to July 2015). Director, Taiwan Education and Research Program, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. May 2004 to present. Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University, August 2011 to June 2014. Deputy Chair, History Department, The George Washington University, July 2009 to August 2011. 1 Senior Associate Dean for Management and Planning, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2005 to August 2006. Associate Dean for Faculty and Student Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. January 2004 to June 2005. Associate Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. July-December 2003. Acting Dean, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. -

The Chongqing Negotiations: a Political Offensive for the Peace and Democracy Policy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CSCanada.net: E-Journals (Canadian Academy of Oriental and Occidental Culture,... ISSN 1927-0232 [Print] Higher Education of Social Science ISSN 1927-0240 [Online] Vol. 19, No. 1, 2020, pp. 40-45 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/11788 www.cscanada.org The Chongqing Negotiations: A Political Offensive for the Peace and Democracy Policy WANG Jin[a],* [a]Chongqing Hongyan Revolutionary History Museum, Chongqing, ended up with victory. Along with the victory, the most China. important, urgent and real political issue facing the KMT *Corresponding author. and the CPC was how to distribute the right to accept Supported by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage: surrender. The dispute between the KMT and the CPC Demonstration Project of Revolutionary History Museum Education on campus. over the right to accept surrender was not just a military issue, but a political one as well, which would involve the Received 24 May 2020; accepted 6 August 2020 move direction of the post-war China and fundamental Published online 26 September 2020 changes in domestic political landscape. Chiang Kai-shek gave orders to He Yingqin at the Abstract midnight: externally to issue an ultimatum to the highest In response to changes in the domestic and international commander of Japanese army, demanding a response with situations around the victory of the anti-Japanese war, the 24 hours to such surrender conditions as ceasing military Kuomintang (KMT) and the Communist Party of China operations, maintaining public order, protecting public (CPC) adjusted their established strategic deployments and private properties, and deferring to KMT troops; in due course to cope with the new post-war domestic while internally requiring the KMT troops to follow political and military landscapes. -

Cross-Border Data Transfer Piloting – Hainan Free Trade Port Policy Briefing | December 2020

Sino-German Cooperation on Industrie 4.0 Cross-Border Data Transfer Piloting – Hainan Free Trade Port Policy Briefing | December 2020 Recently, a number of local governments have been releasing different implementation plans relating to cross-border data transfer. The exploration of facilitating the safe and orderly flow of data across borders has been put on the agenda and is progressing step by step. Current regulatory framework China's regulations and standards on data cross-border transfer are still in the process of being developed. Although China has formulated laws and regulations on cyber security and data flows, specific regulations on cross-border data flow are still not in place. Relevant Articles in Released Documents: A security assessment system for data cross-border transfer was first specified in the Cybersecurity Law in 2017: “Critical information infrastructure operators that gather or produce personal information or important data during operations within the mainland territory of the People’s Republic of China, shall store it within mainland China. Where due to business requirements it is truly necessary to provide it outside the mainland, they shall follow the measures jointly formulated by the state cybersecurity and informatization departments and the relevant departments of the State Council to conduct a security assessment; where laws and administrative regulations provide otherwise, follow those provisions.” (Article 37)1 Based on the Cybersecurity Law, several regulations and guidance on the security assessment of cross-border transfer of personal information or important data have been published, including Security Assessment Method on Personal Information and Important Data Cross-Border Transfer (Draft) and Information Security Technology- Guidelines for Data Cross-Border Transfer Security Assessment (Draft).