Emerging Infectious Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporting of Diseases and Conditions Regulation, Amendment, M.R. 289/2014

THE PUBLIC HEALTH ACT LOI SUR LA SANTÉ PUBLIQUE (C.C.S.M. c. P210) (c. P210 de la C.P.L.M.) Reporting of Diseases and Conditions Règlement modifiant le Règlement sur la Regulation, amendment déclaration de maladies et d'affections Regulation 289/2014 Règlement 289/2014 Registered December 23, 2014 Date d'enregistrement : le 23 décembre 2014 Manitoba Regulation 37/2009 amended Modification du R.M. 37/2009 1 The Reporting of Diseases and 1 Le présent règlement modifie le Conditions Regulation , Manitoba Règlement sur la déclaration de maladies et Regulation 37/2009, is amended by this d'affections , R.M. 37/2009. regulation. 2 Schedules A and B are replaced with 2 Les annexes A et B sont remplacées Schedules A and B to this regulation. par les annexes A et B du présent règlement. Coming into force Entrée en vigueur 3 This regulation comes into force on 3 Le présent règlement entre en vigueur January 1, 2015, or on the day it is registered le 1 er janvier 2015 ou à la date de son under The Statutes and Regulations Act , enregistrement en vertu de Loi sur les textes whichever is later. législatifs et réglementaires , si cette date est postérieure. December 19, 2014 Minister of Health/La ministre de la Santé, 19 décembre 2014 Sharon Blady 1 SCHEDULE A (Section 1) 1 The following diseases are diseases requiring contact notification in accordance with the disease-specific protocol. Common name Scientific or technical name of disease or its infectious agent Chancroid Haemophilus ducreyi Chlamydia Chlamydia trachomatis (including Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) serovars) Gonorrhea Neisseria gonorrhoeae HIV Human immunodeficiency virus Syphilis Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum Tuberculosis Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mycobacterium africanum Mycobacterium canetti Mycobacterium caprae Mycobacterium microti Mycobacterium pinnipedii Mycobacterium bovis (excluding M. -

Profile of Janet Hemingway

PROFILE PROFILE Profile of Janet Hemingway Ann Griswold grandfather worked in the mines. At around Science Writer age five, Hemingway’s grandfather presented her with a pair of retired “pit” ponies that had pulled coal trucks in the mine but had Asthewheelsofabiplaneapproachadesolate resistance, and helped develop life-saving never been ridden. “I was kind of plopped airfield in the Solomon Islands, a man wear- quinolone antimalarial drugs (1). In her In- on top of one, and off we went,” she recalls. ing only a loincloth breaks through the brush, augural Article (2), Hemingway explores Much of the next few years was spent brandishing a spear and a flail. From behind the increasing challenge of insecticide re- outdoors “running riot” with ponies Cap- the plane’s windows four biologists watch sistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anoph- tain and Blaze, a Labrador-sheep dog cross with wary eyes and silently map an escape eles funestus mosquitoes, malaria vectors named Rinty, and a growing menagerie of route. “You’re thinking, ‘What am I sup- prevalent in the southern African country birds, frogs, and animals that family and posed to do here?’” recalls Janet Hemingway, fi of Malawi. The ndings reveal that pyreth- neighbors left in her care. “It was every Director of the Liverpool School of Tropical roids, the most effective antimalarial insec- girl’s dream, I suppose, trying to sort out Medicine, International Director of the Joint ticides known to date, are under siege by Centre for Infectious Disease Research, and these two little ponies and everything re- resistant variants of Anopheles, and in- lated to animals and the outdoors.” a recently elected member of the National creased monitoring in the impoverished “ Soon, Hemingway’s family moved and Academy of Sciences. -

Reportable Disease Surveillance in Virginia, 2013

Reportable Disease Surveillance in Virginia, 2013 Marissa J. Levine, MD, MPH State Health Commissioner Report Production Team: Division of Surveillance and Investigation, Division of Disease Prevention, Division of Environmental Epidemiology, and Division of Immunization Virginia Department of Health Post Office Box 2448 Richmond, Virginia 23218 www.vdh.virginia.gov ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In addition to the employees of the work units listed below, the Office of Epidemiology would like to acknowledge the contributions of all those engaged in disease surveillance and control activities across the state throughout the year. We appreciate the commitment to public health of all epidemiology staff in local and district health departments and the Regional and Central Offices, as well as the conscientious work of nurses, environmental health specialists, infection preventionists, physicians, laboratory staff, and administrators. These persons report or manage disease surveillance data on an ongoing basis and diligently strive to control morbidity in Virginia. This report would not be possible without the efforts of all those who collect and follow up on morbidity reports. Divisions in the Virginia Department of Health Office of Epidemiology Disease Prevention Telephone: 804-864-7964 Environmental Epidemiology Telephone: 804-864-8182 Immunization Telephone: 804-864-8055 Surveillance and Investigation Telephone: 804-864-8141 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 -

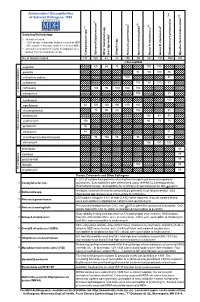

Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Selected Pathogens, 1999

✔ Antimicrobial Susceptibilities * * † 7 of Selected Pathogens, 1999 8 e † a 2 ✔ ✔ † 3 ✔ † 4 5 6 culosis * r 1 urium spp. m L spp. Sampling Methodology 2 L † all isolates tested * ~ 20% sample of statewide isolates received at MDH spp. ~10% sample of statewide isolates received at MDH Salmonella ** all isolates tested from 7-county metropolitan area oup A streptococci ✔ oup B streptococci r isolates from a normally sterile site r Other (non-typhoidal) G Campylobacter Salmonella typhi Shigella Neisseria gonorrhoeae Neisseria meningitidis G Streptococcus pneumoni Mycobacterium tube No. of Isolates Tested 131 160 43 20 250 55 162 192 559 163 123456 123456% Susceptib123456le 123456123456 123456 123451623456 123451623456 ampicillin 1234561234566012345686 123456 15123456123456 100 100 123456123456 123451623451623451623451623456 123456 penicillin 123456123456123456123456123456 98100 100 76 123456 123456123456123456123456123456123456123456123456 123456 123451623451623451623456 123451623451623456 123456 cefuroxime sodium 123456123456123456123456 100123456123456123456 81 123456 123456123456123456123456123456123456123456123456 123456 cefotaxime 123451623451623451623451623456 100 100100 83 123456 123456123456123456123456123456 123456123456123456123456 123456 123456123456123456123456 ceftriaxone 123456 100 95 100 100 100 123451623451623451623456 -lactam antibiotics 123456123456123456123456123456 123456123456123456123456 β 123451623451623451623451623456 123451623456 123456 meropenem 123456123456123456123456123456 100 123456123456 83 123456 123456123456123456123456123456123456123456123456 -

Microbial NAD Metabolism: Lessons from Comparative Genomics

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth Scholarship Faculty Work 9-2009 Microbial NAD Metabolism: Lessons from Comparative Genomics Francesca Gazzaniga Rebecca Stebbins Sheila Z. Chang Mark A. McPeek Dartmouth College Charles Brenner Carver College of Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Genetics and Genomics Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Microbiology Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Gazzaniga, Francesca; Stebbins, Rebecca; Chang, Sheila Z.; McPeek, Mark A.; and Brenner, Charles, "Microbial NAD Metabolism: Lessons from Comparative Genomics" (2009). Dartmouth Scholarship. 1191. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/1191 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICROBIOLOGY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY REVIEWS, Sept. 2009, p. 529–541 Vol. 73, No. 3 1092-2172/09/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/MMBR.00042-08 Copyright © 2009, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Microbial NAD Metabolism: Lessons from Comparative Genomics Francesca Gazzaniga,1,2 Rebecca Stebbins,1,2 Sheila Z. Chang,1,2 Mark A. McPeek,2 and Charles Brenner1,3* Departments of Genetics and Biochemistry and Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire -

Yourthe Magazine for Alumni and Friends 2011 – 2012

UNIVERSITY yourTHE MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 2011 – 2012 A celebration of excellence HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE ROYAL VISIT HM The Queen is seen here wearing a pair of virtual reality glasses during the ground-breaking ceremony at the University’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre page 6 Alumni merchandise Joe Scarborough prints University tie In 2005, to celebrate the University’s Centenary, Sheffield artist Joe Scarborough In 100% silk with multiple (Hon LittD 2008) painted Our University, generously funded by the Sheffield University University shields Association of former students. Sales of the limited edition signed prints raised over Price: £18 (incl VAT) £18,000 for undergraduate scholarships. The University has now commissioned Joe Delivery: £1.00 UK; to paint a sister work entitled Our Students’ Journey which hangs in the Students’ Union. £1.30 Europe; £18 It depicts all aspects of student life including the RAG boat race and parade, student £1.70 rest of world (INCL VAT) officer elections and summer activities in Weston Park. We are delighted to be offering 500 limited edition signed prints. All proceeds will again provide scholarships for gifted students in need of financial support, £40 and to help the University’s Alumni Foundation which distributes grants (INCL VAT) to student clubs and societies. Our Students’ Journey Limited edition signed prints, measuring 19” x 17”, are unframed and packed in protective cardboard tubes and priced at £40.00 (incl VAT). Our University A very limited number of these prints (unsigned) are still available. Measuring 19” x 17”, they are unframed and packed in protective cardboard tubes and priced at £15.00 (incl VAT). -

The Old Testament Is Dying a Diagnosis and Recommended Treatment 1St Edition Download Free

THE OLD TESTAMENT IS DYING A DIAGNOSIS AND RECOMMENDED TREATMENT 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Brent A Strawn | 9780801048883 | | | | | David T. Lamb Strawn offers a few other concrete suggestions about how to save the Old Testament, illustrating several of these by looking at the book of Deuteronomy as a model for second language acquisition. Retrieved 27 August The United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC currently recommend that individuals who have been diagnosed and treated for gonorrhea avoid sexual contact with others until at least one week past the final day of treatment in order to prevent the spread of the bacterium. Brent Strawn reminds us of the Old Testament's important role in Christian faith and practice, criticizes current misunderstandings that contribute to its neglect, and offers ways to revitalize its use in the church. None, burning with urinationvaginal dischargedischarge from the penispelvic paintesticular pain [1]. Stunted language learners either: leave faith behind altogether; remain Christian, but look to other resources for how to live their lives; or balkanize in communities that prefer to speak something akin to baby talk — a pidgin-like form of the Old Testament and Bible as a whole — or, worse still, some sort of creole. Geoff, thanks for the reference. Log in. The guest easily identified the passage The Old Testament Is Dying A Diagnosis and Recommended Treatment 1st edition the New Testament, but the Old Testament passage was a swing, and a miss. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. -

Smutty Alchemy

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2021-01-18 Smutty Alchemy Smith, Mallory E. Land Smith, M. E. L. (2021). Smutty Alchemy (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113019 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Smutty Alchemy by Mallory E. Land Smith A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2021 © Mallory E. Land Smith 2021 MELS ii Abstract Sina Queyras, in the essay “Lyric Conceptualism: A Manifesto in Progress,” describes the Lyric Conceptualist as a poet capable of recognizing the effects of disparate movements and employing a variety of lyric, conceptual, and language poetry techniques to continue to innovate in poetry without dismissing the work of other schools of poetic thought. Queyras sees the lyric conceptualist as an artistic curator who collects, modifies, selects, synthesizes, and adapts, to create verse that is both conceptual and accessible, using relevant materials and techniques from the past and present. This dissertation responds to Queyras’s idea with a collection of original poems in the lyric conceptualist mode, supported by a critical exegesis of that work. -

ASTMH 65Th Annual Meeting Atlanta Marriott Marquis and Hilton Atlanta Atlanta, GA Pre-Registration List As of October 27, 2016

ASTMH 65th Annual Meeting Atlanta Marriott Marquis and Hilton Atlanta Atlanta, GA Pre-Registration List as of October 27, 2016 *John Aaskov, PhD FRCPath Denise Abud Oladokun Adedamola Adesunloye, Queensland University of Technology Sanofi Pastuer Federal Ministry of Health(FMC) Australia USA Nigeria Neetu Abad Manfred M K Accrombessi Grace Adeya CDC Benin GHSC-PSM/Chemonics United States USA *Jane Winnie Achan, Clinical *Tochukwu Abadom MRC Unit, The Gambia Bwaka Mpia Ado Blackpool Victoria Hospital, United Gambia McKIng Consulting Corporation/ EPI Kingdom DRC Nigeria *Nicole L. Achee, PhD Dem. Republic of Congo Univ of Notre Dame *Shaymaa Abdalal, MD USA Joseph Ado-Yobo Tulane School of Public Hlth Ghana USA Salissou Adamou Bathiri Onchocerciasis & Lymphatic *Valentine Adolphe *Agatha Aboe, MBChB; DO Niger PSI Sightsavers USA Ghana *David P. Adams, PhD MPH MSc Dept of Community Medicine, Mercer Yaw Asare Afrane *Ayokunle Abogan Univ Sch of Medicine Kenya Medical Research Institute Natl Malaria Programme USA Kenya Botswana *John H. Adams, PhD Suneth Agampodi, MBBS MSc *Melanie Abongwa, MSc University of South Florida Coll of Pub Univ of Sri Lanka Iowa State University Hlth Sri Lanka USA USA *Kokila Agarwal, DRPH MBBS MPH *Ahmed Abd El Wahed Abou El Nasr, *Matthew Adams MCHIP/JHPIEGO Georg August University Goettingen Univ of Maryland Baltimore USA Germany USA Kodjovi D. Agbodjavou *Jennifer Abrahams, MD Marc Adamy Jhpiego Corp University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medicines for Malaria Venture Togo Hospital Switzerland USA Rakesh Aggarwal, MD DM *David Addiss, MD MPH Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Inst of Lauren Abrams, GA Task Force for Global Hlth Med Sciences Children Without Worms USA India United States *Ahmed Adeel, MD MPH PhD *Selidji Todagbe AGNANDJI Marcelo Claudio Abril United States CERMEL Fundación Mundo Sano Gabon Argentina *Adeshina Israel Adekunle UNSW *Peter C. -

1 Supplementary Material a Major Clade of Prokaryotes with Ancient

Supplementary Material A major clade of prokaryotes with ancient adaptations to life on land Fabia U. Battistuzzi and S. Blair Hedges Data assembly and phylogenetic analyses Protein data set: Amino acid sequences of 25 protein-coding genes (“proteins”) were concatenated in an alignment of 18,586 amino acid sites and 283 species. These proteins included: 15 ribosomal proteins (RPL1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 13, 16; RPS2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11), four genes (RNA polymerase alpha, beta, and gamma subunits, Transcription antitermination factor NusG) from the functional category of Transcription, three proteins (Elongation factor G, Elongation factor Tu, Translation initiation factor IF2) of the Translation, Ribosomal Structure and Biogenesis functional category, one protein (DNA polymerase III, beta subunit) of the DNA Replication, Recombination and repair category, one protein (Preprotein translocase SecY) of the Cell Motility and Secretion category, and one protein (O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase) of the Posttranslational Modification, Protein Turnover, Chaperones category, as annotated in the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) (Tatusov et al. 2001). After removal of multiple strains of the same species, GBlocks 0.91b (Castresana 2000) was applied to each protein in the concatenation to delete poorly aligned sites (i.e., sites with gaps in more than 50% of the species and conserved in less than 50% of the species) with the following parameters: minimum number of sequences for a conserved position: 110, minimum number of sequences for a flank position: 110, maximum number of contiguous non-conserved positions: 32000, allowed gap positions: with half. The signal-to-noise ratio was determined by altering the “minimum length of a block” parameter. -

Nebraska Reportable Disease Chart

Nebraska Reportable Diseases Title 173 Regulations Immediate Notification: Douglas Co. (402)444-7214 (after hrs 402- 444-7000) Lancaster Co (402) 441-8053 (after hrs 402-440-1817) All Other Counties 402-471-1983 Nebraska Public Health Laboratory 24/7 pager 402-888-5588 Labs- automated ELR Labs reporting manually Healthcare providers Updated 5/3/2017 Condition immediate within 7 days monthly immediate within 7 days monthly immediate within 7 days monthly Acinetobacter spp . (all species) x Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), as described in 173 NAC 1- 005.01C2 xxx Adenovirus x Aeromonas spp. x Amebae-associated infection (Acanthamoeba spp, Entamoeba histolytica , and Naegleria fowleri )xxx Anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) * ^ xx x Arboviral infections (including, but not limited to, West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, Western Equine encephalitis virus, Chikungunya virus, Rift Valley fever virus, Zika and Dengue virus) xxx Astrovirus x Babesiosis (Babesia species) x x x Botulism (Clostridium botulinum )* x x x Brucellosis (Brucella abortus^, B. melitensis^, and B. suis)*^ xx x Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) pseudomallei *^ xx x Campylobacteriosis (Campylobacter species )Do not forward to NPHL for banking or subtyping unless requested xxx Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (suspected or confirmed)^** xx x Carbon monoxide poisoning (Use break point for non-smokers) xxx Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi ) ± x x x Chikungunya virus xxx Citrobacter spp. x Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae x Chlamydia trachomatis infections (nonspecific urethritis, cervicitis, salpingitis, neonatal conjunctivitis, pneumonia)± xxx Cholera (Vibrio cholerae ) ^ x x x Clostridium difficile xxx Coccidiodomycosis (Coccidioides immitis/posadasii )xx x Coronavirus (Not MERS) x Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease [transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (14-3-3 protein from CSF or any laboratory analysis of brain tissue suggestive of CJD)] xxx Cryptosporidiosis (C. -

University of Ghana College of Basic and Applied Sciences by Shirley Victoria Simpson (10551058) This Thesis Is Submitted To

UNIVERSITY OF GHANA COLLEGE OF BASIC AND APPLIED SCIENCES ISOLATION AND CHARACTERIZATION of Haemophilus ducreyi STRAINS FROM CHILDREN WITH CUTANEOUS LESIONS IN YAWS ENDEMIC REGIONS, GHANA BY SHIRLEY VICTORIA SIMPSON (10551058) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MPHIL MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES DEGREE JULY, 2017 DECLARATION This is to certify that this thesis is the result of research undertaken by me, Shirley Victoria Simpson towards the award of Master of Philosophy in Molecular Cell Biology of Infectious Diseases in the Department of Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology, School of Biological Sciences, College of Basic And Applied Sciences, University of Ghana. Signature--------------------------------------- Date-------------------------- Shirley Victoria Simpson (Candidate) Signature--------------------------------------- Date----------------------- Prof. Kennedy Kwasi Addo (Supervisor) Signature------------------------------------ Date----------------------- Dr. Lydia Mosi (Co-Supervisor) i ABSTRACT Recent discovery of cutaneous H. ducreyi has complicated the epidemiology of Yaws in endemic countries. Yaws and H. ducreyi ulcers are clinically indistinguishable from each other and some other causes of skin ulcerations. The aim of the study was to isolate and characterize H. ducreyi strains from lesions of children in yaws-endemic areas. Symptomatic patients were first screened with Dual Path Platform (DPP-RDT) Syphilis Screen & Confirm test kit (Chembio, Medford, New York) for yaws. Lesion exudates were tested by culture for H. ducreyi and real-time multiplex PCR assays were used to identify T.p subsp. pertenue DNA and H. ducreyi DNA. Azithromycin (AZT) resistance markers were screened for in T.p subsp. pertenue PCR positives. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced to detect the presence of other pathogenic bacteria.