A Case Study of Ottawa's Fletcher Wildlife Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SARNIA CITY COUNCIL September 9, 2013 4:00 P.M. COUNCIL CHAMBERS, CITY HALL SARNIA, ONTARIO AGENDA Page Closed Meeting

SARNIA CITY COUNCIL September 9, 2013 4:00 p.m. COUNCIL CHAMBERS, CITY HALL SARNIA, ONTARIO AGENDA Page Closed Meeting - 3:40 p.m. Under Section 239 (2) of the Municipal Act (b) personal matters about an identifiable individual, including municipal employees or local board with respect to the City Manager Position (c) a proposed or pending acquisition or disposition of land by the municipality with respect to the Bayside Mall "O CANADA" OPENING PRAYER Pastor Phil Kazek, 1st Baptist Church REPORT OF THE CLOSED MEETING Disclosures of Pecuniary Interest (Direct or Indirect) and the General Nature Thereof DELEGATIONS 11 1. "Juiced" Bluewater Slo-Pitch Team - Canadian Championship Mens 'D' Division 2. Sarnia FC - Cheque Presentation 13-32 3. St. Clair River Area of Concern - Claude Lafrance, St. Clair River Remedial Action Plan Coordinator 33 4. Robert Clark - Concerns Regarding Council Members Running in Provincial/Federal Elections 35-46 5. Centennial Celebration Committee - Legacy Project Team - Refined Legacy Project Page 1 of 303 Page RESOLUTIONS: Moved by Councillor McEachran, seconded by Councillor Gillis CORRESPONDENCE 47-49 1. City Solicitor/Clerk, dated August 22, 2013, regarding City Hall – Chiller A/C units That Council approve the sole source purchase and installation of a used 2 year old 125 Ton Trane roof top chiller from Abram Refrigeration & Systems for City Hall at a price of $111,936.00 (including non- rebateable portion of HST). That Council approve the funding of the roof top chiller from the City Hall Building Reserve in the amount of $80,000.00 and from the Energy Management Reserve in the amount of $31,936.00. -

Ottawa Food Action Plan Is a Community Response to Local Food Issues and Concerns

Otawa Food Acton Plan The Otawa Food Acton Plan is a community response to local food issues and concerns. Food for All has provided the structure, supports and resources, linkages to academic researchers, community partners and organizatons, and a forum to explore food issues together, but these proposals have been writen, researched, and edited largely by community members. The Acton Plan Proposals are community solutons, and the document is a living document. 2012 BACK TO TOP Ottawa Food Action Plan is a community response to local food issues and concerns. Food for All is a community process that involves everybody – residents, government, students, researchers, and organizations. The research, writing and editing work that went into this Food Action Plan has been a collaborative effort: the Food Action Plan proposals have been researched and written by policy writing teams made up of Ottawa community members. It was then reviewed, edited and further researched by a team of volunteer editors from the community, as well as the Food for All Steering Committee and Food for All project partners. Food for All has provided the structure, supports and resources, linkages between academic researchers, community partners and organizations, and a forum to explore food issues together. The Action Plan Proposals are community solutions based on research and evidence, and the document is a living document. This work was guided by the Food for All Steering Committee. Food for All Steering Committee Food for All would like to thank our team of Community -

Revised 2021-08

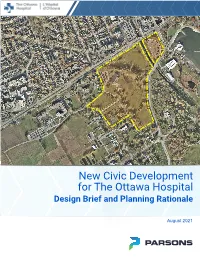

New Civic Development for The Ottawa Hospital Design Brief and Planning Rationale – Master Site Plan August 5th 2021 New Civic Development for The Ottawa Hospital Design Brief and Planning Rationale - Master Site Plan Applications for: Site Plan Control, Master Site Plan and Lifting of Holding Zone August 5th 2021 Prepared by: Parsons with HDR and GBA Page 1 New Civic Development for The Ottawa Hospital Design Brief and Planning Rationale - Master Site Plan August 5th 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Local Context .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Site Significance ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Existing Potential for Transportation Network .......................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Site Topography and Open Space ............................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 DESIGN BRIEF .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Design Vision and Design -

The Plan for Canada's Capital

Judicial i This page is intentionally left blank for printing purposes. ii The Plan for Canada’s Capital 2017 to 2067 NATIONAL CAPITAL COMMISSION June 2016 iii The Capital of an extensive country, rapidly growing in population and wealth, possessed of almost unlimited water power for manufacturing purposes, and with a location admirably adapted not only for the building of a great city, but a city of unusual beauty and attractiveness. (…) Not only is Ottawa sure to become the centre of a large and populous district, but the fact that it is the Capital of an immense country whose future greatness is only beginning to unfold, (…) and that it be a city which will reflect the character of the nation, and the dignity, stability, and good taste of its citizens. Frederick Todd, 1903 “Preliminary Report to the Ottawa Improvement Commission” pp.1-2 iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For more than a century, the National Capital Commission (NCC) and its predecessors have embraced urban planning to promote the development, conservation and improvement of the National Capital Region, with the aim of ensuring that the nature and character of the seat of the Government of Canada is in accordance with its national significance. The consequences of these planning efforts have been the creation of parks and open spaces, public shorelines, campuses and clusters of government institutions, monuments and symbolic boulevards. This plan charts the future of federal lands in the National Capital Region between Canada’s sesquicentennial in 2017 and its bicentennial in 2067. It will shape the use of federal lands, buildings, parks, infrastructure and symbolic spaces to fulfill the vision of Canada’s Capital as a symbol of our country’s history, diversity and democratic values, in a dynamic and sustainable manner. -

7 Maclean Street: Site Plan Control Application

• 7 MACLEAN STREET: SITE PLAN CONTROL APPLICATION Planning Rationale 2B Developments January 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: Fotenn Planning + Design 223 McLeod Street Ottawa, ON K2P 0Z8 fotenn.com January 20, 2020 CONTENTS 1 1.0 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 Surrounding Area and Site Context .....................................................................................................................2 3.0 Proposed Development .......................................................................................................................................9 4.0 Policy and Regulatory Framework .................................................................................................................... 12 5.0 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................ 25 Planning Rationale 2B Developments January 2020 1.0 1 INTRODUCTION Fotenn Consultants Inc., acting as agents for 2B Developments, is pleased to submit the enclosed Site Plan Control Application to facilitate the proposed development on the lands municipally known as 7 Maclean Street in the City of Ottawa. 1.1 Property History As per the historic aerial imagery as referenced through the City of Ottawa’s GeoOttawa database, the building on the subject property has existed since at least 1928. 1.2 Application History -

A Day in Ottawa"

"A Day in Ottawa" Gecreëerd door : Cityseeker 20 Locaties in uw favorieten National War Memorial "Powerful War Monument" Fresh flowers often grace the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, an unnamed Canadian victim of the First World War. Towering above are 22 figures frozen in bronze as they rush forward into battle. Nurses, pilots, soldiers and sailors all represent tales of self-sacrifice and courage. Though prominently located in the busy downtown core, National War Memorial by Yatmandu becomes the center of attention every November 11 at 11a, when the country marks Remembrance Day in honor of the men and women who paid the ultimate price for freedom. www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/nati Wellington Street, Confederation Square, Ottawa ON onal-inventory-canadian-memorials/details/9429 Parliament Hill "The Seat of Power" Parliament Hill is the political heart of Canada. Situated on a bluff overlooking the Ottawa River, it is actually a collection of three turn-of-the- century Gothic structures known as the East Block, Centre Block and West Block. The West Block and East Block contain the offices of Members of Parliament. The House of Commons and the Senate are located in the by Hudation Centre Block, with its soaring Peace Tower. www.ottawatourism.ca/ottawa-insider/parliament-hill/ Wellington Street, Ottawa ON Peace Tower "Symbol of Nationhood" The Peace Tower dominates Parliament Hill, soaring over 90 meters (300 feet) high above Ottawa, while the Canadian flag unfurls gently over its topmost turret. A fine monument symbolic of the country's storied past, as well as a concrete tribute to lives lost in World War I, this Gothic Revival structure is iconic. -

Magnolias – Spring's First Star Attraction

Friends of the Central Experimental Farm Spring 2011 Newsletter Volume 23 No. 2 Magnolias – Spring’s First Star Attraction (AAFC) collection is relatively small, with fewer than 100 specimens, the majority of which are less than 15 years old. (See Page 6 for the location of magnolias around the Farm.) A hidden treasure Nestled in the north end of the Arboretum, just out of sight from Prince of Wales Drive, rests a grove of a dozen or so mature magnolias and several young, newer cultivars. A hidden treasure, this unique collection is a concise representation of the various magnolia species that can tolerate Ottawa’s harsh northern winters. Not all of the magnolia species and cultivars in this collection, however, are hardy enough to survive just anywhere in Ottawa. Several factors such as topography and genetic selection figure prominently in the existence of these wonderful specimens. The cold air tunnel/funnel In 1967, the first train passed through the newly constructed Dow’s Lake train f f i l c tunnel (now the O-train tunnel). h c n i Previously, the track was above ground. H . The construction of the tunnel, which R included a deep trench extending through Magnolia x loebneri ‘Leonard Messel’ and Drumstick primula ( Primula denticulata ) the north end of the Arboretum, had an in the scented border, Ornamental Gardens interesting effect on the climate in that part of the Arboretum. The cold winter air Why has the collection of magnolias at Arboretum to welcome spring. Before the that once sat in the valley below the the Arboretum been such a success? lilacs, crab apples, and cherries bloom, north-facing escarpment could now Crispin Wood, Lead Hand, Arboretum, magnolias are the star attraction. -

Glebe Report

Glebe C.C. planning in progress stay tuned Bravo and thanks to everyone who and will appear as the Working made the Save our Community Group's recommendation to Council. Centre Rally a huge success! On In addition to thanking everyone June 20, over 1,000 local residents who took part in the rally, the rallied at Lansdowne Park to give GCCRWC thanks Doreen Drolet who overwhelming support for retaining conceived it and organized the the Glebe and Ottawa South Com- sidewalk chalking campaign, Janet munity Centres at their current Harris for photography, Glebe Photo sites. At the end of the meeting, for processing, Wallack's for Suzanne McGlashan, the Commis- donating the paint, Ian Van Lock for sioner of Community Services, organizing the banner and poster withdrew the Brewer Park proposal painting, and thanks all residents as the recommended option, though and businesses who gave support it will still appear as one of the with the petition. options in the Report to Council CRITICAL TIME LINES this fall. This was good news to Aug. 31 Reviews, changes & both communities who had voiced additions to Draft Report completed consistent and reasoned opposition Sept. 6 Draft Report com- to the planned complex since intro- pleted duction in early May. Sept. 16 Final Report com- Does this mean the fight for the pleted Glebe Community Centre is over and Oct. 9 Final Report to we can relax for the summer? No, Community Services & Operations not until plans developed over the Committee (CSOC) summer receive City Council ap- Oct. 16 Final Report to City Council for approval Photo: Janet Harris proval on October 16th. -

Official Plan and Zoning

May 11, 2018 ACS2018-PIE-PS-0056 NOTICE OF PLANNING COMMITTEE Dear Sir/Madam: Re: Official Plan and Zoning - Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus – Part of 930 Carling Avenue and 520 Preston Street This is to advise you that the above-noted matter will be considered by the City of Ottawa Planning Committee on Tuesday, May 22, 2018. The Planning Committee meeting will begin at 9:30 a.m. in the Champlain Room, City Hall, 110 Laurier Avenue West, Ottawa. You are welcome to attend the meeting and present your views. Attached is a copy of the report outlining the Departmental recommendations, including a copy of the proposed Official Plan Amendment. The Planning Committee will consider any written submissions in respect to this matter if provided to the Committee Co-ordinator of the Planning Committee at 110 Laurier Avenue West, Ottawa, K1P 1J1 or by fax at 613-580-9609 or by e-mail at [email protected]. If you wish to speak to the Committee please call the Committee Coordinator, Melanie Duffenais at 613-580-2424, extension 20113 in advance of the meeting and preferably, by at least 4:30 p.m. on the day before the meeting. If you wish to listen to this meeting via audiocast on Ottawa.ca, you may do so by accessing the URL below when the meeting is underway: http://app05.ottawa.ca/sirepub/agendaminutes/index_en.aspx If you wish to be notified of the adoption of the proposed Official Plan Amendment, or of the refusal of the request to amend the official plan, you must make a written request to the City of Ottawa to the attention of Sean Moore, Planning, Infrastructure and Economic Development Department, 110 Laurier Avenue West, 4th floor, Ottawa, Ontario K1P 1J1 by facsimile at 613-580-2576, or e-mail at [email protected]. -

Glebe Report - 2 N EWS Thank You and Farewell from Lynn Smyth CLOWNS CHILDREN's WEAR DESIGN STUDIO Centre Residents

The Snowflake Specia BY INEZ BERG ers and cookies. Every appetite was filled and Once again a great Glebe community tradition was there were still leftovers celebrated. to share with the needy. Many children them- The December 7th Snow- busied flake Special, organized selves making Christmas decorations. and sponsored by the Glebe Neighbourhood Activities The Dnipro Ukrainian Danc- Group, had a turnout that ers, perennial favourites filled the Community Centre. at this event, were the The weather cooperated too, highlight of the evening. covering the streets with After their spirited dancing just enough fresh, sparkling they invited the children snow to create a winter in the audience to join wonderland for the carol- them. A long, colourful, lers making their rounds undulating ribbon of laugh- in horsedrawn wagons. The ing, dancing children mild temperature also threaded its way back and forth across the Main contributed to everyones up with Hall while the grown-ups their snowsuits in the Main Hall. But just' enjoyment of the hay rides. for the clapped time. A great journey home. As as real are the happy mem- Then the evening com- for the finale to a special per- children, they ories of a special community menced inside with Domenic ran back formance. and forth, event. D'Arcy as Master of Ceremon- their balloons wafting les. A number of girls Though Santa wasn't there, high under the domed ceil- from the Ottawa Dance Ac- a huge Christmas tree had ing, like impatient kites. ademy, dressed in eye been set up for people to daz- Slowly, as carols were zling costumes, provided lemie wrapped gifts under. -

Leaf out in the Arboretum by Zoe Panchen So It Was a Delight to Be Back in the Arboretum Studying the Leaf out of the Woody Plants at a More Leisurely Pace

Friends of the Central Experimental Farm Spring 2017 Newsletter Volume 29 No. 2 Leaf Out in the Arboretum By Zoe Panchen So it was a delight to be back in the Arboretum studying the leaf out of the woody plants at a more leisurely pace. We defined leaf out as the date on which leaves on at least three branches of the tree or shrub had unfurled to the point where their final shape could be seen. Spring in the Arboretum Here in Ottawa we often joke that if we blink we will miss spring, so it was quite surprising to see that in 2012 it was almost two months (59 days) from the first species leafing out to the last species leafing out. In 2013 and 2014 I was unable to monitor the last few species leafing out, but in 2015 and 2016 the leaf out start to finish was a week and a half shy of two months, still quite long at 49 and 47 days respectively. At the Arboretum the first woody species leaf out n usually about the second week in April, but e h c in 2012 it was the last week in March. There n a P were some very warm days in early spring e o 2012 and perhaps this was the reason for Z the early start to leaf out that year. Ginkgo Tree (Ginkgo biloba) leafing out, May 14, 2012 Deciduous species such as maples and oaks are not the only species that leaf out in n 2012, I was invited to join a team of when I skied through the trees. -

Urban Lands Plan

CAPITAL URBAN LANDS PLAN CAPITAL URBAN LANDS Message from the Chief Executive Officer Among the many assets under the stewardship of the National Capital Commission, the Capital urban lands are without doubt the most generally interspersed into the Capital's urban fabric. As such, this first Capital Urban Lands Plan is critical to ensuring the appropriate integration of these complex holdings into the National Capital Region as part of the NCC's new framework for planning the capital. Within the broader context of the Plan for Canada's Capital 2017-2067 this Plan sets out an astute basis for planning, developing, improving and conserving the NCC's urban lands. It complements and supports other plans developed by the NCC for the Greenbelt, Gatineau Park and the Capital Core Area. It gives me great pleasure that this Plan is the result of an in-depth process of public consultation, expert analysis and detailed planning. The passion of citizens and stakeholders for our urban parks, river shorelines and heritage buildings is fully reflected in this document. It builds on the thoughtful plans and hard work of the Commission and its predecessors that have guided the Capital's evolution since 1898. This Plan defines a long-term vision that will guide decisions for many years to come, helping those who do business with the NCC by providing clear and precise direction for the development of facilities and activities on federal lands, and more specifically on NCC lands. This Plan will serve as the primary guide for the NCC’s Capital Stewardship activities and for federal approvals pertaining to Capital Urban Lands.