Integrating the Army Geospatial Enterprise: Synchronizing Geospatial-Intelligence to the Dismounted Soldier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESOURCES Forgotten Battles, Forgotten Maps

79 RESOURCES Forgotten Battles, Forgotten Maps: Resources for Reconstructing Historical Topographical Intelligence Using Army Map Service Materials John M. Anderson opographical intelligence is the information gathered about terrain, facilities, and transportation networks in enemy territory.1 This in- Tformation, collected to aid in military operations, remains a noble cartographic resource that historical geographers can use in a variety of ways. One map collection based on topographical intelligence languishes underused and underappreciated in many university map libraries. Falling somewhere between the glorious old maps and the newest digital cartographic products are the venerable United States Army Map Service (AMS) materials. This essay will briefly discuss the history of the AMS and how its materi- als became available in library collections. This essay also will explain topo- graphical intelligence’s importance and present the results of a survey of an AMS map collection that identified map series with high potential as research sources. Finally, it will present the locations of AMS map collections and work- ing aids for interpreting the material. Army Map Service—Background Although the American military did not have a centralized system for producing and distributing maps at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Army was addressing wartime map requirements before 1941. During 1940 and 1941, the Engineer Reproduction Plant, the AMS’s predecessor, concentrated on printing topographic maps depicting Army camps and ma- neuver areas. Construction of a new building to house the Engineer Repro- John M. Anderson is Map Librarian in the Cartographic Information Center of the Department of Geogra- phy and Anthropology at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. -

The Army's New TOPOCOM

mCtnY[ OFflCf OHlCf Of tllUfLU P"tfALl CHIEr COMMmltC emm ._ 10PlCUPlIC IfPUTI C_IIIIK OfACfI EMCIMm CHlff OF SIAfr AIYlSOtI DO , U11IIUSlRAlIIE STiff .., ~., " ,' i..' ,j u' r ,,, r........ 0 ft' OIRECIOIAU ADP SYSTEMS P!RSOIHEl CO~::~~~EI A~~~~I~~S ~:~:~:; 1:::I~::l ~~:~: or OFfICE OfflCf I OfflCf 1 OffiCE flClllllES TECHMICll ! STAFf f""''''· ..·..·.. ·....•.. ,~·~ ..•........·,,··..""··....t OIIECIOIITE DllfClOIAlE '"ECTOIAlE or Of ruMS. or PlUCIES I lOVlMcn REQUIIEMElIIS OPfRATiOIS SYSTEMS , "!RIllMe DEPAlTMfMTS r......·"....,..,·..·....·i..·..·· ··,,·.......·..·,· r....··"'·....··..,.. 'i,..'·r..·'·..·....·........ ·~ ..l DEPAITMEMT OEPAITMEMT OfPAltMm OfPAl1lm D£PARTIEMT COMPUTER Of CR.,tIC or or or or SfRVICfS TECMIIUl APPlIEt ARTS I FlElI SERVICES cEODISI CARTDGUPBY ,t DlSTaIIUT"M oFllm cmu SUtORDlMm 1 COMIOOS r....·'·..H.<..• ......••••..• ..j".....,..t»>...•..•...........i 10TH 6411 U.S. "I' mimi UGIIEU tMClMm TOPoeUPMIC ..mUOM IRITRllOM UIOtATORIES FIG. 1. Organizational chart of the new U. S. Army Topographic Command, TOPOCOM. BRIG. GE EDWARD T. PODUFALY* U. S. Army Topographic Command Washington, D. C. 20315 The Army's New TOPOCOM The main reason for the new organization is to keep abreast of the new equip ment, skills and techniques that are already upon us or are just over the horizon. T IS INDEED A PLEASURE and privilege to geodesy, I would like to introduce to you a I appear before two such distinguished pro new organization-the U. S. Army Topo fessional groups. Duling the past few days graphic Command, or TOPOCOM, for short. I you have read professional papers and lis must report also that the well-known name of tened to learned presentations of a very Army Map Service has ceased to exist be technical nature. -

Inventario Mapas Cuba, Haiti Y RD.Pdf

Colección de Documentos y Mapas Inventario de Mapas de Cuba Gaveta 43 Título Autor Año Clasificación Serie U.S. Department of Commerce; National Oceanic and Atlantic Coast. Straits of Florida and Atmospheric Administration; 1993 C 55.418/7:11013/993 Nautical Charts approaches. National Ocean Service; Coast and Geodetic Survey. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Baracoa, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1815 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Caibarién, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1708 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Camagüey, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1809 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Cándido González, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1716 Agency. (Air). Central America. Cuba-Mexico. Defense Mapping Agency. 1995 D 5.356:27120/995 Nautical Charts Yucatan Channel. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Ciego de Ávila, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1712 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Cienfuegos, Cuba. 1997 1501ANF1711 Agency. (Air). Industrial Engineering Drafting Cuba Sugar Mills and Refineries. 1951 MC-62 Economic Co. Joint Operations Graphic Guane, Cuba. Defense Mapping Agency. 1995 1501ANF1606 (Air). Army Map Service; Corps of Habana. 1959 No tiene Topographic Engineers. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Holguín, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1810 Agency. (Air). Colección de Documentos y Mapas Inventario de Mapas de Cuba Gaveta 43 Army Map Service; Corps of La Habana (Havana), Cuba. 1961 1301XNF17 Topographic. Engineers. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic La Habana, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1706 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Nueva Gerona, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1709 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Nuevitas, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1805 Agency. -

Foreign Maps

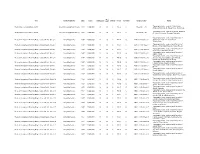

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Case Topography, towns, roads for Virgin Islands, West Indies - Lesser Antilles - North American Geographical Society 1927 1:1,000,000 N 39 6 W1-A G Sheet N.E. - 20 Antigua & Barbuda, St. Kitts & Nevis, Guadeloupe Topography, towns, roads for Dominica, Matinique, West Indies - Lesser Antilles - South American Geographical Society 1927 1:1,000,000 N 39 6 W1-A G Sheet N.D. - 20 St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenada, Barbados Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 1 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 1 Afghanistan, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 2 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 2 Bhutan, China, India, Mongolia, Nepal, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 3 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 3 China, Korea, Mongolia, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 4 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 4 Japan, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 5 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 5 Armenia, Azerbaijan, -

A Short History of Army Intelligence

A Short History of Army Intelligence by Michael E. Bigelow, Command Historian, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command Introduction On July 1, 2012, the Military Intelligence (MI) Branch turned fi fty years old. When it was established in 1962, it was the Army’s fi rst new branch since the Transportation Corps had been formed twenty years earlier. Today, it remains one of the youngest of the Army’s fi fteen basic branches (only Aviation and Special Forces are newer). Yet, while the MI Branch is a relatively recent addition, intelligence operations and functions in the Army stretch back to the Revolutionary War. This article will trace the development of Army Intelligence since the 18th century. This evolution was marked by a slow, but steady progress in establishing itself as a permanent and essential component of the Army and its operations. Army Intelligence in the Revolutionary War In July 1775, GEN George Washington assumed command of the newly established Continental Army near Boston, Massachusetts. Over the next eight years, he dem- onstrated a keen understanding of the importance of MI. Facing British forces that usually outmatched and often outnumbered his own, Washington needed good intelligence to exploit any weaknesses of his adversary while masking those of his own army. With intelligence so imperative to his army’s success, Washington acted as his own chief of intelligence and personally scrutinized the information that came into his headquarters. To gather information about the enemy, the American com- mander depended on the traditional intelligence sources avail- able in the 18th century: scouts and spies. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

Historical Handbook of NGA Leaders

Contents Introduction . i Leader Biographies . ii Tables National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Directors . 58 National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Deputy Directors . 59 Defense Mapping Agency Directors . 60 Defense Mapping Agency Deputy Directors . 61 Defense Mapping Agency Directors, Management and Technology . 62 National Photographic Interpretation Center Directors . 63 Central Imagery Office Directors . 64 Defense Dissemination Program Office Directors . 65 List of Acronyms . 66 Index . 68 • ii • Introduction Wisdom has it that you cannot tell the players without a program. You now have a program. We designed this Historical Handbook of National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Leaders as a useful reference work for anyone who needs fundamental information on the leaders of the NGA. We have included those colleagues over the years who directed the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the component agencies and services that came together to initiate NGA-NIMA history in 1996. The NGA History Program Staff did not celebrate these individuals in this setting, although in reading any of these short biographies you will quickly realize that we have much to celebrate. Rather, this practical book is designed to permit anyone to reach back for leadership information to satisfy any personal or professional requirement from analysis, to heritage, to speechwriting, to retirement ceremonies, to report composition, and on into an endless array of possible tasks that need support in this way. We also intend to use this book to inform the public, especially young people and students, about the nature of the people who brought NGA to its present state of expertise. -

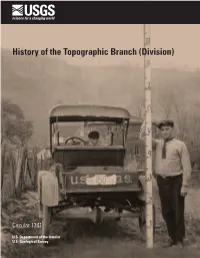

History of the Topographic Branch (Division)

History of the Topographic Branch (Division) Circular 1341 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Rodman holding stadia rod for topographer George S. Druhot near Job, W. Va., 1921. 2 Report Title John F. Steward, a member of the Powell Survey, in Glen Canyon, Colorado River. Shown with field equipment including gun, pick, map case, and canteen. Kane County, Utah, 1872. Photographs We have included these photographs as a separate section to illustrate some of the ideas and provide portraits of some of the people discussed. These photographs were not a part of the original document and are not the complete set that would be required to appropriately rep- resent the manuscript; rather, they are a sample of those available from the time period and history discussed. Figure 1. The Aneroid barometer was used to measure differences in elevation. It was more convenient than the mercurial or Figure 2. The Odometer was used to measure distance traveled by counting the cistern barometer but less reliable. revolutions of a wheel (1871). Figure 3. The Berger theodolite was a precision instrument used Figure 4. Clarence King, the first Director of the U.S. Geological for measuring horizontal and vertical angles. Manufactured by Survey (1879–81). C.L. Berger & Sons, Boston (circa 1901). Figure 6. A U.S. Geological Survey pack train carries men and equipment up a steep slope while mapping the Mount Goddard, California, Quadrangle (circa 1907). Figure 5. John Wesley Powell, the second Director of the U.S. Geological Survey (1881–94). Figure 8. Copper plate engraving of topographic maps provided a permanent record. -

Cartographic World War II Records Guide

Cartographic World War II Records Guide This guide was compiled from various descriptions from our online catalog at catalog.archives.gov. The following description fields are included: Series Title Dates - Some dates include both when the series was compiled or maintained as well as the time period that the records cover. NAID (National Archives Identifier) - This is a unique identifier that allows us locate materials in our holdings. A series description (scope and content) is included for each series entry. Type of archival materials - This field describes what type of records the series includes. Arrangement - This field provides you with information on how the records have been arranged and organized. This may help you understand what kind of information is needed to pull the records. Finding aid - If there is another finding that we can provide you to help locate specific folders, boxes or individual records, it will be listed here. All of these finding aids will be available as a paper copy and/or as a digital file in our research room. Access and use restrictions - If there are any access or use restrictions on the records, they will be listed and explained here. Extent - This notes how many items or folders are included in the series. Digitized - This field will tell you if any of the records in the series are digitized and available in our catalog. Any digitized records are available at catalog.arhcives.gov by entering the provided NAID in the search bar. Selection note: The selected series were chosen to be included based on their research value pertaining to World War II and the particular time period of 1939 - 1945. -

American Cartographic Transformations During the Cold War John Cloud

American Cartographic Transformations during the Cold War John Cloud ABSTRACT: A great convergence of cartography, secrecy, and power occurred during the Cold War. In the American case, a complex series of interactions between secret and classified programs and institutions and their publicly accessible counterparts accomplished both traditional and novel objec- tives of military geographic intelligence. This process also yielded the World Geodetic System, a mass- centered “figure of the earth” at accuracies adequate for warfare with intercontinental ballistic missiles. A structural and institutional separation developed between enterprises charged with overhead data acquisition systems, which were classified at increasingly high levels of secrecy, and those responsible for data reduction, analysis, and mapping systems, which remained largely unclassified and publicly accessible, in part to conceal the classified data acquisition systems. This structural separation desta- bilized photogrammetric mapping by displacing systems that privileged dimensional stability with systems that privileged novel sensor types more appropriate to Cold War geo-political objectives and constraints. Eventually, photogrammetric mapping systems were re-stabilized by successfully implement- ing analytical solutions imposed in digital mapping and data management systems. This achievement re-privileged dimensional stability, now redefined to the new media of geo-referenced digital data. In the early 1970s these developments culminated in advanced research projects -

Chapter 6. Replenishing the Research Capital, 1947–1950

Chapter 6. Replenishing the Research Capital, 1947–1950 We must concurrently carry on scientific investigations whose economic benefits cannot be immediately reflected in the balance sheet. It has been abundantly demonstrated that the pure or basic science of today is the applied science of tomorrow. We must develop by painstaking research methods the techniques for the discovery of new mineral deposits.1 —William E. Wrather The treaties signed in 1947 to end hostilities in World War II ensured that 1948 would be for the United States a year of official peace as well as a Presidential election. As part of his campaign, Truman promptly set out his domestic agenda. The President, in his State of the Union Message to Congress on January 7, 1948, set five goals for the Nation. America should secure the essential human rights for all its citizens, protect and develop its human resources, conserve and use its natural resources to contribute more effectively to public welfare, raise the standard of living for all its citizens by strengthening the economy and sharing more widely its products, and achieve “world peace based on principles of freedom and justice and the equality of all nations.”2 To do so, Truman emphasized, required overcoming the problem of inflation that threatened the realization of all of these goals. He called for a national health program, increased support for education and farmers, the conservation of natural resources, and raising the minimum wage from 40 to 75 cents an hour. On February 2, Truman sent to the 80th Congress a special message on civil rights,3 urging the legislators to pass measures to ensure more effective statutory protection of the right to vote and to end poll taxes, establish a Fair Employment Practices Commission with authority to stop discrimination by employers and labor unions, end inequity in interstate travel, and act on claims by Americans of Japanese descent confined against their will during the war years. -

The Evolution of Geospatial Intelligence

From AFIO's Intelligencer Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, Fall/Winter 2015. www.afio.com ©2015 Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic to compromise on a disputed area. These hard-working cartographers and analysts collectively contributed to the Dayton Peace Accords, Guide to Study of Intelligence leading to a temporary, but significant, suspension of regional violence. In this case, the professional lesson did not go unlearned. Combining people and talent from eight agencies and offices the following year into the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) reflected initiatives underway, but also spoke to the wisdom of asking those involved in defense imagery The Evolution of Geospatial and mapping, including DMA, to emulate the Dayton success on a more permanent basis. Intelligence and the National Of course, the agency’s enabling legislation Geospatial-Intelligence Agency simply brought people together and initially could do nothing more. For many months after the creation of NIMA, imagery analysis and geospatial informa- by Dr. Gary E. Weir tion services within the agency remained in separate and culturally distinct worlds. Seeing the potential in integration, a number of senior leaders recom- Something Happened in Dayton mended strongly that the agency integrate the talents assembled under the NIMA umbrella. Strong cultural n 1 November 1995, President Clinton called identities on all sides at times made the idea of car- on the warring factions in Bosnia to end tographers and other geospatial specialists regularly Othe conflict that had cost over 300,000 Serb, emulating the Dayton experience a very difficult and Croat, and Muslim lives since 1991. He invited their almost unlikely prospect.