Chapter 6. Replenishing the Research Capital, 1947–1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating the Army Geospatial Enterprise: Synchronizing Geospatial-Intelligence to the Dismounted Soldier

Integrating the Army Geospatial Enterprise: Synchronizing Geospatial-Intelligence to the Dismounted Soldier by James E. Richards Bachelors of Science in Mechanical Engineering, United States Military Academy, 2001 Master of Science, Engineering Management, University of Missouri-Rolla, Rolla, Missouri, 2005 SUBMITTED TO THE SYSTEM DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT PROGRAM IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2010 The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. 1 [This Page Intentionally Left Blank] 2 Army‘s Geospatial Architecture: delivering Geospatial-Intelligence of complex and urban terrain to the dismounted Soldier by James E. Richards ABSTRACT The Army‘s Geospatial Enterprise (AGE) has an emerging identity and value proposition arising from the need to synchronize geospatial information activities across the Army in order to deliver value to military decision makers. Recently, there have been significant efforts towards increasing the capability of the enterprise to create value for its diverse stakeholder base, ranging from the warfighter, to early stage research and development. The AGE has many architectural alternatives to consider as it embarks upon geospatial transformation within the Army, each of these alternatives must deliver value through an increasingly wide range of operating environments characterized by the uncertainty of both future technology and the evolution of future operations. This research focuses on understanding how the Army‘s geospatial foundation data layers propagate through the battlefield and enable well informed tactical decisions. -

RESOURCES Forgotten Battles, Forgotten Maps

79 RESOURCES Forgotten Battles, Forgotten Maps: Resources for Reconstructing Historical Topographical Intelligence Using Army Map Service Materials John M. Anderson opographical intelligence is the information gathered about terrain, facilities, and transportation networks in enemy territory.1 This in- Tformation, collected to aid in military operations, remains a noble cartographic resource that historical geographers can use in a variety of ways. One map collection based on topographical intelligence languishes underused and underappreciated in many university map libraries. Falling somewhere between the glorious old maps and the newest digital cartographic products are the venerable United States Army Map Service (AMS) materials. This essay will briefly discuss the history of the AMS and how its materi- als became available in library collections. This essay also will explain topo- graphical intelligence’s importance and present the results of a survey of an AMS map collection that identified map series with high potential as research sources. Finally, it will present the locations of AMS map collections and work- ing aids for interpreting the material. Army Map Service—Background Although the American military did not have a centralized system for producing and distributing maps at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Army was addressing wartime map requirements before 1941. During 1940 and 1941, the Engineer Reproduction Plant, the AMS’s predecessor, concentrated on printing topographic maps depicting Army camps and ma- neuver areas. Construction of a new building to house the Engineer Repro- John M. Anderson is Map Librarian in the Cartographic Information Center of the Department of Geogra- phy and Anthropology at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. -

The Army's New TOPOCOM

mCtnY[ OFflCf OHlCf Of tllUfLU P"tfALl CHIEr COMMmltC emm ._ 10PlCUPlIC IfPUTI C_IIIIK OfACfI EMCIMm CHlff OF SIAfr AIYlSOtI DO , U11IIUSlRAlIIE STiff .., ~., " ,' i..' ,j u' r ,,, r........ 0 ft' OIRECIOIAU ADP SYSTEMS P!RSOIHEl CO~::~~~EI A~~~~I~~S ~:~:~:; 1:::I~::l ~~:~: or OFfICE OfflCf I OfflCf 1 OffiCE flClllllES TECHMICll ! STAFf f""''''· ..·..·.. ·....•.. ,~·~ ..•........·,,··..""··....t OIIECIOIITE DllfClOIAlE '"ECTOIAlE or Of ruMS. or PlUCIES I lOVlMcn REQUIIEMElIIS OPfRATiOIS SYSTEMS , "!RIllMe DEPAlTMfMTS r......·"....,..,·..·....·i..·..·· ··,,·.......·..·,· r....··"'·....··..,.. 'i,..'·r..·'·..·....·........ ·~ ..l DEPAITMEMT OEPAITMEMT OfPAltMm OfPAl1lm D£PARTIEMT COMPUTER Of CR.,tIC or or or or SfRVICfS TECMIIUl APPlIEt ARTS I FlElI SERVICES cEODISI CARTDGUPBY ,t DlSTaIIUT"M oFllm cmu SUtORDlMm 1 COMIOOS r....·'·..H.<..• ......••••..• ..j".....,..t»>...•..•...........i 10TH 6411 U.S. "I' mimi UGIIEU tMClMm TOPoeUPMIC ..mUOM IRITRllOM UIOtATORIES FIG. 1. Organizational chart of the new U. S. Army Topographic Command, TOPOCOM. BRIG. GE EDWARD T. PODUFALY* U. S. Army Topographic Command Washington, D. C. 20315 The Army's New TOPOCOM The main reason for the new organization is to keep abreast of the new equip ment, skills and techniques that are already upon us or are just over the horizon. T IS INDEED A PLEASURE and privilege to geodesy, I would like to introduce to you a I appear before two such distinguished pro new organization-the U. S. Army Topo fessional groups. Duling the past few days graphic Command, or TOPOCOM, for short. I you have read professional papers and lis must report also that the well-known name of tened to learned presentations of a very Army Map Service has ceased to exist be technical nature. -

![The American Legion 34Th National Convention: Official Program [1952]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9419/the-american-legion-34th-national-convention-official-program-1952-1159419.webp)

The American Legion 34Th National Convention: Official Program [1952]

Mill F 1 1 illl 1 1 IlHIIli TTfl i^niu AUEmJST 25th thru 28th 1952 NEW YORK CITY liifl I- — There’s No Substitute for Old Grand-Dad ou’ll never know how fine a bourbon can be Y until you try Old Grand-Dad — one of Kentucky’s finest whiskies. It goes into new charred white oak casks a superior whiskey. There it ripens until com- pletely matured. Then it is bottled in bond. Enjoy this superb whiskey’s smoothness, mellowness and heart-warming flavor soon. Then you will know why there’s no substitute for Old Grand-Dad "Head of the Bourbon Family.” The Old Grand-Dad Distillery Company Frankfort , Kentucky THIRTY-FOURTH HATIOHAL COHVENTION The American Legion August 25 — A ugust 28, 1952 New York City, New York ik La Societe des La Boutique des American Legion Quarante Hommes et Huit Chapeaux et Huit Chevaux Auxiliary Quarante Femmes Thirty-third Thirty-second Thirty-first Promenade Nationale National Convention Marche Nationale Preamble to the Constitution . of The American Legion OR God and Country, we associate ourselves F together for the following purposes: To up- hold and defend the Constitution of the United States of America; to maintain law and order; to foster and perpetuate a one hundred per cent Americanism; to preserve the memories and incidents of our associations in the Great Wars; to inculcate a sense of individual obligation to the community, state and nation; to combat the autocracy of both the classes and the masses; to make right the master of might; to promote peace and good will on earth; to safeguard and transmit to posterity the principles of justice, freedom, and democracy; to consecrate and sanctify our comradeship by our devotion to mutual helpfulness. -

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture

A War All Our Own: American Rangers and the Emergence of the American Martial Culture by James Sandy, M.A. A Dissertation In HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTORATE IN PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. John R. Milam Chair of Committee Dr. Laura Calkins Dr. Barton Myers Dr. Aliza Wong Mark Sheridan, PhD. Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, James Sandy Texas Tech University, James A. Sandy, May 2016 Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the constant encouragement and tutelage of my committee. They provided the inspiration for me to start this project, and guided me along the way as I slowly molded a very raw idea into the finished product here. Dr. Laura Calkins witnessed the birth of this project in my very first graduate class and has assisted me along every step of the way from raw idea to thesis to completed dissertation. Dr. Calkins has been and will continue to be invaluable mentor and friend throughout my career. Dr. Aliza Wong expanded my mind and horizons during a summer session course on Cultural Theory, which inspired a great deal of the theoretical framework of this work. As a co-chair of my committee, Dr. Barton Myers pushed both the project and myself further and harder than anyone else. The vast scope that this work encompasses proved to be my biggest challenge, but has come out as this works’ greatest strength and defining characteristic. I cannot thank Dr. Myers enough for pushing me out of my comfort zone, and for always providing the firmest yet most encouraging feedback. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56 -

1939 Journal

— — I OCTOBEE TEEM, 1939 STATISTICS Original Appellate Total Number of cases on docket _ _ 15 1, 063 1, 078 Cases disposed of __ 4 942 946 Remaining on docket 11 121 132 Cases disposed of By written opinions 151 By per curiam opinions 97 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 690 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation 8 Number of written opinions 137 Number of admissions to bar 1,016 REFERENCE INDEX Page. Butler, J., death of, announced 73 Butler, J., resolutions of the Bar presented by Attorney Gen- eral Jackson 242 Murphy, J., commission read and oath taken (February 5, 1940) . 146 Eobert H. Jackson, Attorney General, presented his Commis- sion 126 Francis Biddle, Solicitor General, presented 126 Proceedings commemorating 150th Anniversary of Court (February 1, 1940) 136 Address of Attorney General Jackson 136 Address of Charles A. Beardsley, President of American Bar Association 139 Address of the Chief Justice 141 Advisory Committee requested to submit amendments to Eules of Civil Procedure 54 Administrative Office of United States Courts Henry P. Chandler appointed Director 75 Elmore Whitehurst appointed Assistant Director 54 Transfer of appropriations 54,221 Allotment of Justices 158 181208—40 98 — II Page. Disbarment, In the matter of Clyde H. Walker 34 Anna L. Cooke 34,81 David B. Getz 35,81 Walter C. Balderston 46 French B. Loveland (failure to reply to Clerk's communi- cations) 81, 109, 115 Rules of Supreme Court—Rule 41 amended 192 Regulations prescribed in reference to appeals from Court of Claims appearing in 210 U. S. -

Inventario Mapas Cuba, Haiti Y RD.Pdf

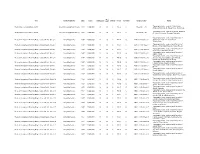

Colección de Documentos y Mapas Inventario de Mapas de Cuba Gaveta 43 Título Autor Año Clasificación Serie U.S. Department of Commerce; National Oceanic and Atlantic Coast. Straits of Florida and Atmospheric Administration; 1993 C 55.418/7:11013/993 Nautical Charts approaches. National Ocean Service; Coast and Geodetic Survey. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Baracoa, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1815 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Caibarién, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1708 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Camagüey, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1809 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Cándido González, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1716 Agency. (Air). Central America. Cuba-Mexico. Defense Mapping Agency. 1995 D 5.356:27120/995 Nautical Charts Yucatan Channel. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Ciego de Ávila, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1712 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Cienfuegos, Cuba. 1997 1501ANF1711 Agency. (Air). Industrial Engineering Drafting Cuba Sugar Mills and Refineries. 1951 MC-62 Economic Co. Joint Operations Graphic Guane, Cuba. Defense Mapping Agency. 1995 1501ANF1606 (Air). Army Map Service; Corps of Habana. 1959 No tiene Topographic Engineers. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Holguín, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1810 Agency. (Air). Colección de Documentos y Mapas Inventario de Mapas de Cuba Gaveta 43 Army Map Service; Corps of La Habana (Havana), Cuba. 1961 1301XNF17 Topographic. Engineers. National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic La Habana, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1706 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Nueva Gerona, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1709 Agency. (Air). National Imagery and Mapping Joint Operations Graphic Nuevitas, Cuba. 1995 1501ANF1805 Agency. -

Foreign Maps

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Case Topography, towns, roads for Virgin Islands, West Indies - Lesser Antilles - North American Geographical Society 1927 1:1,000,000 N 39 6 W1-A G Sheet N.E. - 20 Antigua & Barbuda, St. Kitts & Nevis, Guadeloupe Topography, towns, roads for Dominica, Matinique, West Indies - Lesser Antilles - South American Geographical Society 1927 1:1,000,000 N 39 6 W1-A G Sheet N.D. - 20 St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenada, Barbados Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 1 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 1 Afghanistan, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 2 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 2 Bhutan, China, India, Mongolia, Nepal, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 3 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 3 China, Korea, Mongolia, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 4 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 4 Japan, Russia Topography, towns, roads, airports for parts of Western Hemisphere Planning Maps - Colored Relief - Sheet 5 Army Map Service 1957 1:5,000,000 N 39 6 W1-B G AMS 1, 1130, Sheet 5 Armenia, Azerbaijan, -

A Short History of Army Intelligence

A Short History of Army Intelligence by Michael E. Bigelow, Command Historian, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command Introduction On July 1, 2012, the Military Intelligence (MI) Branch turned fi fty years old. When it was established in 1962, it was the Army’s fi rst new branch since the Transportation Corps had been formed twenty years earlier. Today, it remains one of the youngest of the Army’s fi fteen basic branches (only Aviation and Special Forces are newer). Yet, while the MI Branch is a relatively recent addition, intelligence operations and functions in the Army stretch back to the Revolutionary War. This article will trace the development of Army Intelligence since the 18th century. This evolution was marked by a slow, but steady progress in establishing itself as a permanent and essential component of the Army and its operations. Army Intelligence in the Revolutionary War In July 1775, GEN George Washington assumed command of the newly established Continental Army near Boston, Massachusetts. Over the next eight years, he dem- onstrated a keen understanding of the importance of MI. Facing British forces that usually outmatched and often outnumbered his own, Washington needed good intelligence to exploit any weaknesses of his adversary while masking those of his own army. With intelligence so imperative to his army’s success, Washington acted as his own chief of intelligence and personally scrutinized the information that came into his headquarters. To gather information about the enemy, the American com- mander depended on the traditional intelligence sources avail- able in the 18th century: scouts and spies. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

Historical Handbook of NGA Leaders

Contents Introduction . i Leader Biographies . ii Tables National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Directors . 58 National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Deputy Directors . 59 Defense Mapping Agency Directors . 60 Defense Mapping Agency Deputy Directors . 61 Defense Mapping Agency Directors, Management and Technology . 62 National Photographic Interpretation Center Directors . 63 Central Imagery Office Directors . 64 Defense Dissemination Program Office Directors . 65 List of Acronyms . 66 Index . 68 • ii • Introduction Wisdom has it that you cannot tell the players without a program. You now have a program. We designed this Historical Handbook of National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Leaders as a useful reference work for anyone who needs fundamental information on the leaders of the NGA. We have included those colleagues over the years who directed the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the component agencies and services that came together to initiate NGA-NIMA history in 1996. The NGA History Program Staff did not celebrate these individuals in this setting, although in reading any of these short biographies you will quickly realize that we have much to celebrate. Rather, this practical book is designed to permit anyone to reach back for leadership information to satisfy any personal or professional requirement from analysis, to heritage, to speechwriting, to retirement ceremonies, to report composition, and on into an endless array of possible tasks that need support in this way. We also intend to use this book to inform the public, especially young people and students, about the nature of the people who brought NGA to its present state of expertise.