Alternatives to Hitler. German Resistance Under the Third Reich'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

1 Stephanie Zibell: Vor 80 Jahren: Als Die Hakenkreuzflagge Über

Stephanie Zibell: Vor 80 Jahren: Als die Hakenkreuzflagge über Darmstadt wehte. Kollegiengebäude und Landesverwaltung zwischen Machtergreifung und demokratischem Neubeginn. Vortrag aus Anlass der Gedenkveranstaltung zum 80. Jahrestag der „Machtergreifung“ durch die Nationalsozialisten. Einleitung Als mich Herr Regierungspräsident Baron im vergangenen Jahr ansprach und mich bat, am heutigen Tag einen Vortrag zu halten, habe ich dem Ansinnen insofern gerne entsprochen, als ich mich in meiner Dissertation mit dem in Darmstadt amtierenden hessischen Reichsstatthalter und Gauleiter Jakob Sprenger beschäftigt habe, von dem wir heute noch hören werden, und in meiner Habilitationsschrift mit Ludwig Bergsträsser, der hier in Darmstadt zwischen 1945 und 1948 als erster Regierungspräsident amtiert hat. Ihm, Ludwig Bergsträsser, ist heute eine ganz besondere Ehrung zuteil geworden, über die ich mich persönlich sehr freue: Der bisherige Sitzungssaal Süd ist in Ludwig-Bergsträsser-Saal umbenannt worden. Ich habe davon auch meinem Doktorvater, Prof. Dr. Hans Buchheim, berichtet, der Ludwig Bergsträsser noch persönlich gekannt hat und dafür verantwortlich zeichnet, dass ich mich so intensiv mit Bergsträsser beschäftigt habe. Auch Herr Buchheim, der heute hier anwesend ist, zeigte sich sehr erfreut. Doch wie der Titel meines Vortrags und der einleitende Hinweis auf den Nationalsozialisten Jakob Sprenger bereits andeutet: Es wird in der nächsten Stunde nicht nur Erfreuliches zu hören sein, sondern auch Tragisches und Betrübliches. Ich werde im Folgenden von den Ereignissen berichten, die die nationalsozialistische „Machtübernahme“ am 30. Januar 1933 in Darmstadt, damals Hauptstadt des Volksstaats Hessen, und in Wiesbaden, dem Sitz des Regierungspräsidiums des Regierungsbezirks Wiesbaden der preußischen Provinz Hessen-Nassau, nach sich zog. Das preußische Wiesbaden erwähne ich, weil es vor 1945 im Volksstaat Hessen kein Regierungspräsidium gab. -

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer The 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities May 8, 2014 It is a great privilege to stand before you tonight and deliver the 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities, and to receive this prestigious award in his name. As a child growing-up in Muskegon in the 1950s and 1960s, the name of Charles Hackley was certainly a respected name, if not an icon from Muskegon’s past, after which were named: the hospital in which I was born, the park in which I played, a Manual Training School and Gymnasium, a community college, an athletic field (Hackley Stadium) in which I danced as the Muskegon High School Indian mascot, and an Art Gallery and public library that I frequently visited. Often in going from my home in Lakeside through Glenside and then to Muskegon Heights, we would drive on Hackley Avenue. I have deep feelings about that Hackley name as well as many good memories of this town, Muskegon, where my life journey began. It is really a pleasure to return to Muskegon and accept this honor, after living away in the state of Minnesota for forty-six years. I also want to say thank you to the Friends of the Hackley Public Library, their Board President, Carolyn Madden, and the Director of the Library, Marty Ferriby. This building, in which we gather tonight, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, also holds a very significant place in the life of my family. My great-grandfather, George Alfred Matthews, came from Bristol, England in 1878, and after living in Newaygo and Fremont, settled here in Muskegon and was a very active deacon in this congregation until his death in 1921. -

To Read the Full Text, Click Here

TEXT For Conduct And Innocents (drama in verse) by J. Chester Johnson Copyright © 2015 by J. Chester Johnson 1 Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Germany’s Jeremiah Born 1906 in Breslau, Germany (now, part of Poland) into a prominent, but not particularly religious family, Dietrich Bonhoeffer embraced the teachings of Protestantism early, becoming a well-known theologian and acclaimed writer while still in his twenties. When most of the Church leadership in Germany crumbled under the weight of Nazism, Bonhoeffer and a group of colleagues set about establishing the Confessing Church as a moral and spiritual counterforce. Bonhoeffer also plotted with a group of co-conspirators to overthrow Hitler; toward that end, he participated in organizing efforts to assassinate the Nazi leader. Arrested in April, 1943, Bonhoeffer remained in prison for the rest of his life. Remnants of the Hitler command were so obsessed with Bonhoeffer’s death that they executed him at the Flossenburg concentration camp, located near the Czechoslovakian border, on April 9, 1945, only two weeks before American liberation of the camp. Stripped of clothing, tortured and led naked to the gallows yard, he was then hanged from a tree. In 1930, Dietrich Bonhoeffer arrived here in New York City from Germany with a doctorate of theology and additional graduate work in hand and with some experience as a curate for a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona, Spain. He had been awarded a fellowship to Union Theological Seminary, where he came under the influence of many of the leading theological luminaries of the day, including Reinhold Niebuhr, a major force for social ethics. -

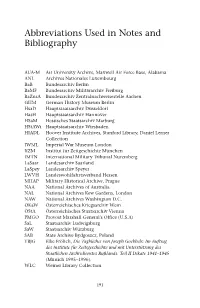

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Document Contains 1,126 Words

No. 19-351 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, a foreign state, and STIFTUNG PREUSSICHER KULTURBESITZ, Petitioners, v. ALAN PHILIPP, et al., Respondents. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ of Certiorari To The United States Court of Appeals For The D.C. Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOINT APPENDIX --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JONATHAN M. FREIMAN NICHOLAS M. O’DONNELL Counsel of Record Counsel of Record TADHG DOOLEY ERIKA L. TODD BENJAMIN M. DANIELS SULLIVAN & WORCESTER LLP DAVID R. ROTH One Post Office Square WIGGIN AND DANA LLP Boston, MA 02109 265 Church Street (617) 338-2814 P.O. Box 1832 [email protected] New Haven, CT 06508-1832 Counsel for Respondents (203) 498-4400 [email protected] DAVID L. HALL WIGGIN AND DANA LLP Two Liberty Place 50 S. 16th Street Suite 2925 Philadelphia, PA 19102 (215) 998-8310 Counsel for Petitioners Petition For Certiorari Filed September 16, 2019 Certiorari Granted July 2, 2020 ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Relevant Docket Entries from the United States District Court for the District -

114 Adolf Reichwein (1937) Der Fliegende Mensch Mit

Journal of Social Science Education Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2014 DOI 10.2390/jsse‐v14‐i2‐1259 Adolf Reichwein (1937) Der fliegende Mensch Mit Anmerkungen von Heinz Schernikau (Kommentar 1) und Tilman Grammes (Kommentar 2) Quelle: Adolf Reichwein. Schaffendes Schulvolk. Tiefenseer Schulschriften 1937–1939. Pädagogische Schriften. Kommentierte Werkausgabe in fünf Bänden, Band 4, herausgegeben und bearbeitet von Karl‐Christoph Lingelbach und Ullrich Amlung. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt 2011, S. 24‐185; Auszüge hier S. 26f., S. 33ff., S. 80‐93 Mit freundlichem Dank an Prof. Dr. Roland Reichwein sowie den Verlag Julius Klinkhardt für die Genehmigung zum Abdruck dieses Auszuges in deutscher Sprache sowie die Publikation einer englischen Übersetzung (Auszug). Vorwort (WA Bd. 4, S. 26f.) wenn sie Pflicht bedeuten. Wenn wir bei Kindern von Mit dieser Schrift lege ich nicht einen Plan vor oder einen Pflicht sprechen, können wir nur die Lust an der Pflicht Vorschlag, wie es gemacht werden sollte, sondern den meinen … Bericht einer Wirklichkeit. Nicht die Gestaltung einer möglichen, einer gedachten Erziehungsgemeinschaft ist II. Wie wir es machen hier vorgezeichnet, sondern die Gestalt einer ver‐ Winter (WA Bd. 4, S. 80‐93) wirklichten, einer bereits geleisteten Arbeit nach‐ 2. Beispiel gezeichnet. Und doch enthält diese Darstellung nicht nur So wie die Vertiefung der geschichtlichen Anschauung ein ‚Bildnis’, sondern öffnet den Blick auf die Gründe und zum dörflichen Schulwinter gehört, führt diese Jahreszeit geistigen Vorgänge, die zu jener Wirklichkeit führten. Es auch ganz von selbst den Umgang mit der Gestalt ist der Versuch, Bericht und Deutung in Einem zu geben... unserer Erde, die Erdkunde, in Betrachtungen hinein, die mehr Überschau als Anschauung sind. -

Review Article Did Weimar Fail?*

Review Article Did Weimar Fail?* Peter Fritzsche University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign What is Weimar without the Republic? Not much, it seems, since for most German historians the plot that holds the story together has been fragile democracy and its demise. "Weimar" is, as numerous subtitles inform us, the "history of the first Ger- man Democracy," the site where democracy surrendered or failed.' The drama of twentieth-century Germany has largely turned on the failure of the Weimar Repub- lic. All the grand scholarly investments in the study of big-business relations, small- town clubs, East Elbian provinces, and a staggering variety of interest groups and political parties have been undertaken to explain more successfully the frailties of the Republic. This focus has been meritorious since it has guided political self- understandings in postwar Germany and indicated possible limits to the legitimacy of modem democracies generally. Even the notable political guru Kevin Phillips has invoked Weimar to warn his Republican clients not to forget "Middle Ameri~a."~ But preoccupation with the fate of the Republic has been so single-minded that it * I would like to thank Fred Jaher, Hany Liebersohn, Glenn Penny, and Joe Perry for their helpful readings of this article. The following books are under review: Frank Bajohr, Werner Johe, and Uwe Lohalm, eds., Zivilisation und Barbarei: Die widerspriichliche Potentiale der Moderne (Hamburg, 1991); Shelley Baranowski, The Sanctity of Rural Life: Nobility, Protestantism, and Nazism in Weimar Prussia -

Displacements and Replacements of the Political in an Unbounded Dictatorship

Polycracy As An A-System Of Rule? Displacements And Replacements Of The Political In An Unbounded Dictatorship Abstract The concept of polycracy is beset by a number of paradoxes: it designates a form of political rule in the absence of such rule. In such circumstances, a multiplicity of social formations, economic and financial agencies and operational functions install themselves anomically at local level and extend independently of and beyond policy and legislation. In doing so, they split and supplant frameworks of the state and of political and societal institutions. This article sets out to trace the lineages of the concept of polycracy and its instantiations in a system of rule that involves a process of political de-structuring. More specifically, the question explored here is what takes place in the destroyed political space and what takes its place in the unbounded state of the Nazi dictatorship. Keywords: polycracy; National Socialist totalitarianism; Nazi regime; party–state relationship; occupying regime; Weimar Republic; quantitatively total state Introduction Even with historical hindsight, the phenomenon termed “totalitarianism” presents a number of conundrums. To start off with, it resists definition. To describe it as a “system of rule” risks contradiction (see Kershaw 1999, 222), because “a- systematicity” is its most pertinent characteristic. As a particular type of modern dictatorship, it has invited comparisons, yet such comparisons remain limited and general (considering e.g. the limited comparability of the National Socialist regime in Germany and the Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union—see Kershaw 1999). The process of political disintegration described by it is bound to leave the concept under-theorised (see Kershaw 1991, 98) and possibly even to impress itself on the theorist as incomprehensible (see Arendt [1951] 1994, viii), both conceptually and politically. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:15-cv-00266 Document 1 Filed 02/23/15 Page 1 of 71 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) Alan PHILIPP, ) 5 Raeburn Close ) London NW11 6UG, United Kingdom, ) ) and ) ) Gerald G. STIEBEL, ) 3716 Old Santa Fe Trail ) Santa Fe, NM 87505, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Case No. ) FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, a foreign ) state, ) ) and ) ) STIFTUNG PREUSSISCHER KULTURBESITZ, ) ) Von-der-Heydt-Str. 16-18 ) 10785 Berlin, Germany, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT This is a civil action by plaintiffs Alan Philipp (“Philipp”), and Gerald G. Stiebel (“Stiebel,” together with Philipp, the “plaintiffs”), for the restitution of a collection of medieval relics known as the “Welfenschatz” or the “Guelph Treasure” now wrongfully in the possession of the defendant Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, a/k/a the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (the “SPK”). The SPK is an instrumentality of the defendant Federal Republic of Germany (“Germany,” together with the SPK, the “defendants”). Case 1:15-cv-00266 Document 1 Filed 02/23/15 Page 2 of 71 INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT 1. This is an action to recover the Welfenschatz, a unique collection of medieval relics and devotional art that was sold by victims of persecution of the Nazi regime under duress, and far below actual market value. Those owners were a consortium of three art dealer firms in Frankfurt: J.&S. Goldschmidt, I. Rosenbaum, and Z.M. Hackenbroch (together, the “Consortium”). Zacharias Max Hackenbroch (“Hackenbroch”), Isaak Rosenbaum (“Rosenbaum”), Saemy Rosenberg (“Rosenberg”), and Julius Falk Goldschmidt (“Goldschmidt”) were the owners of those firms, together with plaintiffs’ ancestors and/or predecessors-in-interest in this action. -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

Für Freiheit Und Recht Der „20

B L Ä T T E R Nr. 79 ZUM LAND Für Freiheit und Recht Der „20. Juli 1944“ und seine Verbindungen in unserer Region Der Umsturzversuch des 20. Juli 1944 wird zu stürzen. Bis zum Sommer 1944 wurden in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland traditio- sogar mehrere Attentats- und Umsturzpläne nell als das zentrale Ereignis des deutschen entwickelt, wieder verworfen oder schlugen Wider standes gegen das NS-Regime gewür- fehl. digt. Auch 75 Jahre danach ist jedoch in der breiten Öffentlichkeit noch immer kaum bekannt, dass es innerhalb der militärischen und der zivilen Opposition schon recht bald Überlegungen gegeben hatte, Adolf Hitler Ludwig Schwamb wurde am 23. Juli 1944 in Frankfurt festgenommen und später nach Berlin überstellt. Am 13. Januar 1945 verurteilte ihn der „Volksgerichtshof“ zum Tode. Zehn Tage später wurde er zusammen mit neun weiteren Verschwörern in der Strafanstalt Berlin-Plötzensee hingerichtet. Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Sämtliche dieser Vorhaben scheiterten an technischen und anderen Unwägbarkeiten, wegen der scharfen Sicherheitsvorkehrungen des NS-Regimes oder am Zaudern der be- teiligten Militärs. Die absolute Mehrheit der Wehrmacht und ihrer Führung stand loyal hinter dem Diktator und Oberbefehlshaber und folgte bis zuletzt willig seiner barbari- schen Kriegs- und Eroberungsstrategie. Der „20. Juli“ war keineswegs nur eine ge- meinsame Aktion von wenigen oppositionel- len Militärs und Vertretern des konservativ- liberalen Bürgertums, sondern konnte sich gleichermaßen auf eine weit verzweigte zivile Widerstandsstruktur stützen. Diese war besonders vom früheren Innenminister des Volksstaates Hessen und Gewerkschaftsfüh- rer Wilhelm Leuschner, seinen Parteifreun- den, den ehemaligen SPD-Reichstagsabge- ordneten Dr. Carlo Mierendorff und Dr. Julius Leber sowie von etlichen weiteren Mitstrei- tern in jahrelanger konspirativer Kleinarbeit im ganzen Reichsgebiet geschaffen worden.