To Read the Full Text, Click Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer David W. Clark Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Clark, David W., "A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer" (1968). Master's Theses. 2118. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1968 David W. Clark A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION AND CRITIQUE OF THE ETHICS OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER by David W. Clark A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, Loyola University, Ohicago, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for !he Degree of Master of Arts J~e 1968 PREFACE This paper is a preliminary investigation of the "Christian Ethics" of Dietrich Bonhoeffer in terms of its self-consistency and sufficiency for moral guidance. As Christian, Bonhoefferts ethic serves as a concrete instance of the ways in which reli gious dogmas are both regulative and formative of human behavioro Accordingly, this paper will study (a) the internal consistency of the revealed data and structural principles within Bonhoef ferts system, and (b) the significance of biblical directives for moral decisionso The question of Bonhoefferfs "success," then, presents a double problem. -

Thomas Lloyd's Bonhoeffer

Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church presents Thomas Lloyd’s Bonhoeffer Sunday, March 17, 2019 4:00 p.m. Sanctuary Welcome Welcome to this afternoon’s performance of Thomas Lloyd’sBonhoeffer . On behalf of the choir, I thank you for attending and hope you will return for our upcoming events - Daryl Robinson’s organ recital on March 31 and our performance of Bach’s St. Mark Passion on April 19. These past ten weeks of rehearsals have been intense, challenging, ear-opening, and ultimately, inspiring. Living, as we have, with the remarkable story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life, intertwined as it was with his fellow theologians and his beloved fiancée, Maria, has taken us on a journey that has profoundly touched each of us. How does one wrap one’s mind around the life of a peace-loving theologian who ultimately participates in a plot to murder Adolf Hitler? Bonhoeffer’s story has challenged us to ponder what is right and wrong, matters of living the faith in challenging times, and how to be courageous. I am deeply grateful to Tom Lloyd for having the courage to tackle the composition of Bonhoeffer. Tom has succeeded in getting inside Dietrich and Maria’s minds and hearts. You hear their struggles. You are moved by a love that ultimately was thwarted by Bonhoeffer’s death at the hands of the Nazi’s. For me personally, the setting of Bonhoeffer’s favorite biblical passage, the Beatitudes, is simply brilliant. Through masterful use of rhythm and bi-tonality, Tom depicts the challenge of living these words. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer The 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities May 8, 2014 It is a great privilege to stand before you tonight and deliver the 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities, and to receive this prestigious award in his name. As a child growing-up in Muskegon in the 1950s and 1960s, the name of Charles Hackley was certainly a respected name, if not an icon from Muskegon’s past, after which were named: the hospital in which I was born, the park in which I played, a Manual Training School and Gymnasium, a community college, an athletic field (Hackley Stadium) in which I danced as the Muskegon High School Indian mascot, and an Art Gallery and public library that I frequently visited. Often in going from my home in Lakeside through Glenside and then to Muskegon Heights, we would drive on Hackley Avenue. I have deep feelings about that Hackley name as well as many good memories of this town, Muskegon, where my life journey began. It is really a pleasure to return to Muskegon and accept this honor, after living away in the state of Minnesota for forty-six years. I also want to say thank you to the Friends of the Hackley Public Library, their Board President, Carolyn Madden, and the Director of the Library, Marty Ferriby. This building, in which we gather tonight, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, also holds a very significant place in the life of my family. My great-grandfather, George Alfred Matthews, came from Bristol, England in 1878, and after living in Newaygo and Fremont, settled here in Muskegon and was a very active deacon in this congregation until his death in 1921. -

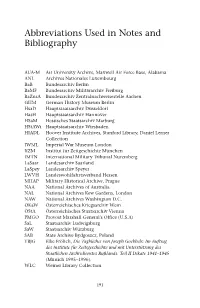

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Stellvertretung As Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Samuel Paul Randall St. Edmund’s College December 2018 Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Abstract Stellvertretung represents a consistent and central hermeneutic for Bonhoeffer. This thesis demonstrates that, in contrast to other translations, a more precise interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s use of Stellvertretung would be ‘vicarious suffering’. For Bonhoeffer Stellvertretung as ‘vicarious suffering’ illuminates not only the action of God in Christ for the sins of the world, but also Christian discipleship as participation in Christ’s suffering for others; to be as Christ: Schuldübernahme. In this understanding of Stellvertretung as vicarious suffering Bonhoeffer demonstrates independence from his Protestant (Lutheran) heritage and reflects an interpretation that bears comparison with broader ecumenical understanding. This study of Bonhoeffer’s writings draws attention to Bonhoeffer’s critical affection towards Catholicism and highlights the theological importance of vicarious suffering during a period of renewal in Catholic theology, popular piety and fictional literature. Although Bonhoeffer references fictional literature in his writings, and indicates its importance in ethical and theological discussion, there has been little attempt to analyse or consider its contribution to Bonhoeffer’s theology. This thesis fills this lacuna in its consideration of the reception by Bonhoeffer of the writings of Georges Bernanos, Reinhold Schneider and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Each of these writers features vicarious suffering, or its conceptual equivalent, as an important motif. According to Bonhoeffer Christian discipleship is the action of vicarious suffering (Stellvertretung) and of Verantwortung (responsibility) in love for others and of taking upon oneself the Schuld that burdens the world. -

The Political Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Ethical Problem of Tyrannicide

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2015 The olitP ical Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Ethical Problem of Tyrannicide Brian Kendall Watson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Brian Kendall, "The oP litical Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Ethical Problem of Tyrannicide" (2015). LSU Master's Theses. 612. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/612 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICAL THEOLOGY OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER AND THE ETHICAL PROBLEM OF TYRANNICIDE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Political Science by Brian K. Watson B.A., Baylor University, 2011 August 2015 PREFACE Who am I? They often tell me I would step from my cell’s confinement calmly, cheerfully, firmly, like a squire from his country-house. Who am I? They often tell me I would talk to my warders freely and friendly and clearly, as though it were mine to command. Who am I? They also tell me I would bear the days of misfortune equably, smilingly, proudly, like one accustomed to win. -

LIVING & EFFECTIVE TRANSCRIPT — EPISODE 5 — Bonhoeffer's Dilemma

LIVING & EFFECTIVE TRANSCRIPT — EPISODE 5 — Bonhoeffer’s Dilemma Richard Clark: I'm going to admit something up front here: the idea of producing this episode terrifies me. Just by making the choice to explore the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, I'm risking failure. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is a complex figure. Someone who has been misunderstood and misrepresented time and again, and those misunderstandings have real implications. Maybe his most well known act is, his involvement in a failed attempt to kill Adolf Hitler, was the playing out of an ethical conundrum that resonates with anyone in times of political and social upheaval. What draws me to Dietrich is his failure. And not only did he fail, he failed in a dramatic, public way, to the point that his failure became a major part of his legacy. And we're not talking about a small mishap here; the stakes of what Bonhoeffer was trying to do were huge. Look, I don't know about you, but I'm pretty familiar with this concept of failure. It's not something you ever get used to. For me, failure is pretty immobilising. It's not just the fact of failure, it's the fear of it, too. A lot of times my fear of being exposed, wronged, or rejected leads me to shut down, hide away, or wallow in self pity or shame, or even just coast. What separates Bonhoeffer from so many of his peers, though, was that even though he failed, he chose to act. So how did a man so immersed in social and political chaos find meaning and purpose? How did he have the confidence to go on when he so often found himself to be wrong and misguided? Reggie Williams: So you're not going to rely on some set of principles. -

John Young / Bonhoeffer in Harlem

John Young | BONHOEFFER IN HARLEM by Sylvia Dominique Volz Quite early on I decided to do some works as a tribute to Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It will be an abstract tapestry, based on the stained glass window found at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. The Abyssinian Baptist Church is where Dietrich Bonhoeffer discovered black gospel music in 1930, and discovered a genuine connection to the marginal and oppressed blacks of New York. Through this experience, Bonhoeffer returned to Germany with the understanding to defend the “marginalized, the vulnerable, and the oppressed.” The colour scheme of this tapestry is quite loud and celebratory – these colours were taken directly from the stained glass in the Harlem church. This tapestry will be like listening to black gospel music in St. Matthäus. I have also included pictures of a series of drawings celebrating the life of Bonhoeffer, they are chalk drawings on blackboard paint on paper, I will be doing eight of them, and they will be framed. John Young, June 2008 April 9, 2009 marks the 64th anniversary of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s execution by the Nazis. A few days later, on April 13, Easter Sunday, the exhibition Bonhoeffer in Harlem will open in the place he was ordained a minister in 1931, St. Matthäus in Berlin-Tiergarten. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Lutheran theologian, proponent of ecumenism, peace activist, and one of the central figures in the German Resistance against Hitler and Nazi racial ideology, was born the sixth of eight children in Breslau on February 4, 1906. After his father, a professor for psychiatry and neurology, accepted a position at the university in Berlin, the family moved to Berlin-Grunewald in 1912. -

Responsibility for Future Generations (PDF)

THE POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CHURCH Responsibility for Future Generations PRIMING THE PUMP: When you think about the future the children of St. Andrew face, what fills you with foreboding? INTRODUCTION: “AFTER TEN YEARS” 1 1. Written at Christmas 1942, a few months prior to arrest on April 5, 1943 2. Addressed to co-conspirators a. Eberhard Bethge: student, confessing partner, and dear friend b. Hans von Dohnanyi: brother-in-law and mastermind of conspiracy c. Hans Oster: chief of Central Section in Military Intelligence Office 3. Included as Prologue in Letters and Papers from Prison a. Bridges gap between final months of freedom and imprisonment b. “New Year’s” reflection, taking stock of events of events and issues EXPOSING THE MASQUERADE OF EVIL 1. Nazis clothed themselves in “garb of relative historical and social justice” 2 2. In extreme situation like Nazi Germany may have to stand firm with truthful/responsible deeds rather than words 3. Failed attempts to stand firm a. Reasonable people: reason will fix things b. Fanatical people: attack evil with purity of principle c. People of conscience: torn apart by conflicting ethical factors d. Dutiful people: obey commands of those in authority e. People of freedom: value necessary deed more highly than untarnished conscience and reputation f. Privately virtuous: close eyes to injustices around them 4. Standing firm by engaging in responsible/truthful action a. Ultimate not reason, principles, conscience, duty, freedom, virtue b. Obedient and responsible action toward God and other humans c. Critiques any approach focused too exclusively on consequences, motives, or any one ethical factor d. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

PA RT 1 the Interrogation Period April–July 1943

PA R T 1 The Interrogation Period April–July 1943 1. From Karl Bonhoeffer[1] 43 Berlin-Charl[ottenburg] 9, April 11, 1943 Dear Dietrich, I wanted to send you a greeting from us and tell you that we are always thinking of you. We know you and are therefore confident that everything will turn for the better, and hopefully soon. Despite all the anxiety we are now experiencing, we have the happy memory, to which we will hold on, of the cantata Lobe den Herren,[2] which you rehearsed and performed with your brothers and sisters and the grandchildren for my seventy-fifth birthday.[3] Hopefully, we can speak with you soon. Kindest regards from Mama, Renate, and her fiancée,[4] and your old Father With permission we have sent you a package on Wednesday the seventh, with bread and some other groceries, a blanket, and a woolen undershirt, and such. [1.] NL, A 76,2; handwritten; the letterhead reads: “Professor Dr. Bonhoeffer. Medical Privy Counselor”; the line below the return address “Berlin-Charl.” reads: “Marienburger Allee 43” (the letterhead and information about the sender are the same in subsequent letters from Karl Bonhoeffer). Previously published in LPP, 21. [2.] Helmut Walcha, Lobe den Herren (Praise the Lord); a cantata for choirs, wind instruments, and organ. [3.] On March 31, 1943; see DB-ER, 785; and Bethge and Gremmels, Life in Pictures, centenary ed., 134. [4.] Renate Schleicher and Eberhard Bethge. During the first six months of Bonhoef- fer’s incarceration in Tegel, Eberhard Bethge’s name was never mentioned directly for safety reasons.