PA RT 1 the Interrogation Period April–July 1943

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1968 A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer David W. Clark Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Clark, David W., "A Preliminary Investigation and Critique of the Ethics of Dietrich Bonhoeffer" (1968). Master's Theses. 2118. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/2118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1968 David W. Clark A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION AND CRITIQUE OF THE ETHICS OF DIETRICH BONHOEFFER by David W. Clark A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, Loyola University, Ohicago, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for !he Degree of Master of Arts J~e 1968 PREFACE This paper is a preliminary investigation of the "Christian Ethics" of Dietrich Bonhoeffer in terms of its self-consistency and sufficiency for moral guidance. As Christian, Bonhoefferts ethic serves as a concrete instance of the ways in which reli gious dogmas are both regulative and formative of human behavioro Accordingly, this paper will study (a) the internal consistency of the revealed data and structural principles within Bonhoef ferts system, and (b) the significance of biblical directives for moral decisionso The question of Bonhoefferfs "success," then, presents a double problem. -

For Love of the World: Bonhoeffer's Resistance to Hitler and the Nazis

Word & World Volume 38, Number 4 Fall 2018 For Love of the World: Bonhoeffer’s Resistance to Hitler and the Nazis MARK S. BROCKER Pastor Bonhoeffer Becomes a Conspirator On June 17, 1940, in the early stages of World War II, France surrendered to Germany. Dietrich Bonhoeffer and his closest friend and colleague, Eberhard Bethge, were having a leisurely lunch in a café in the Baltic village of Memel. They were in East Prussia doing three visitations on behalf of the Confessing Church, which had issued the Barmen Declaration in 1934 and struggled against the inroads of the Nazis into the life of the church. They had met with a group of pastors in the morning, and Bonhoeffer was scheduled to preach in a Confessing Church congregation that evening. According to Bethge, when the announcement of France’s surrender came over the café loudspeaker, “the people around the tables could hardly contain them- selves; they jumped up, and some even climbed on the chairs. With outstretched arms they sang ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ and the Horst Wessel song. We had stood up, too.” Bethge was shocked, however, when “Bonhoeffer raised his arm Bonhoeffer’s Christian faith and his roles as theologian and pastor led him to active engagement with the very dangerous world around him, which led to his imprisonment. In prison he was led to examine and deepen his commit- ments both to this world and to the coming kingdom of Christ in ways that each informed and enriched the other. 363 Brocker in the regulation Hitler salute.” Recognizing his friend’s shock, Bonhoeffer whis- pered to him, “Raise your arm! Are you crazy?” Shortly thereafter Bonhoeffer added: “We shall have to run risks for very different things now, but not for that salute!”1 In Bethge’s assessment, Bonhoeffer’s “double life” truly began in that moment. -

Dietrich Bonhoeffer Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Table of Contents

Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration n The Minister’s Toolbox Spring 2011 Dietrich Bonhoeffer Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Table of Contents FROM THE DEAN EDITORIAL TEAM A Tale of Two Declarations Dean Timothy George 2 HISTORY Director of External Relations Tal Prince (M.Div. ’01) A Spoke in the Wheel Confessing Christ in Nazi Germany Editor 4 Betsy Childs CULTURE Costly Grace and Christian Designer Witness Jesse Palmer 12 TheVeryIdea.com Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration Photography Sheri Herum Chase Kuhn MINISTRY Rebecca Long Caroline Summers The Minister’s Toolbox 16 Why Ministers Buy Books For details on the cover image, please see page 4. COMMUNITY Beeson was created using Adobe InDesign CS4, Adobe PhotoShop CS4, CorelDraw X4, Beeson Portrait Microsoft Word 2007, and Bitstream typefaces Paula Davis Modern 20 and AlineaSans.AlineaSerif. 20 ...at this critical moment in our life together, we Community News Revisiting the Manhattan Declaration find it important to stand together in a common struggle, to practice what I Beeson Alumni once called “an ecumenism of the trenches.” Beeson Divinity School Carolyn McKinstry Tells Her Story Samford University 800 Lakeshore Drive Dean Timothy George Birmingham, AL 35229 MINISTRY (205) 726-2991 www.beesondivinity.com Every Person a Pastor ©2011-2012 Beeson Divinity School 28 eeson is affiliated with the National Association of Evangelicals and is accredited by the Association of Theological Schools in the United States Band Canada. Samford University is an Equal Opportunity Institution that complies with applicable law prohibiting discrimination in its educational and employment ROW 1; A Tale of Two Declarations 2; A Spoke in the Wheel 4; policies and does not unlawfully discriminate on the Costly Grace and Christian Witness 12; ROW 2;The Minister’s Toolbox 16; basis of race, color, sex, age, disability, or national or ethnic origin. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Beyond All Cost

BEYOND ALL COST A Play about Dietrich Bonhoeffer By Thomas J. Gardiner Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co. Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Co. Inc.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING 95church.com © 1977 & 1993 by Thomas J. Gardiner Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://95church.com/beyond-all-cost Beyond All Cost - 2 - DEDICATION Grateful acknowledgement is hereby made to: Harper & Row, Macmillan Publishing Company, and Christian Kaiser Verlag for their permission to quote from the works of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Eberhard Bethge. The Chorus of Prisoners is dramatized from Bonhoeffer's poem "Night Voices in Tegel," used by permission of SCM Press, London. My thanks to Edward Tolk for his translations from “Mein Kampf,” and to Union Theological Library for allowing me access to their special collections. STORY OF THE PLAY The play tells the true story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a pastor who led the resistance to Hitler in the German church. Narrated by Eberhard Bethge, his personal friend, companion and biographer, the play follows Bonhoeffer from his years as a seminary professor in northern Germany, through the turbulent challenges presented by Hitler’s efforts to seize and wield power in both the state and the church. Bonhoeffer is seen leading his students to organize an underground seminary, to distribute clandestine anti-Nazi literature, and eventually to declare open public defiance of Hitler’s authority. -

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Honoring and Perpetuating the Legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer The 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities May 8, 2014 It is a great privilege to stand before you tonight and deliver the 2014 Charles H. Hackley Distinguished Lecture in the Humanities, and to receive this prestigious award in his name. As a child growing-up in Muskegon in the 1950s and 1960s, the name of Charles Hackley was certainly a respected name, if not an icon from Muskegon’s past, after which were named: the hospital in which I was born, the park in which I played, a Manual Training School and Gymnasium, a community college, an athletic field (Hackley Stadium) in which I danced as the Muskegon High School Indian mascot, and an Art Gallery and public library that I frequently visited. Often in going from my home in Lakeside through Glenside and then to Muskegon Heights, we would drive on Hackley Avenue. I have deep feelings about that Hackley name as well as many good memories of this town, Muskegon, where my life journey began. It is really a pleasure to return to Muskegon and accept this honor, after living away in the state of Minnesota for forty-six years. I also want to say thank you to the Friends of the Hackley Public Library, their Board President, Carolyn Madden, and the Director of the Library, Marty Ferriby. This building, in which we gather tonight, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, also holds a very significant place in the life of my family. My great-grandfather, George Alfred Matthews, came from Bristol, England in 1878, and after living in Newaygo and Fremont, settled here in Muskegon and was a very active deacon in this congregation until his death in 1921. -

To Read the Full Text, Click Here

TEXT For Conduct And Innocents (drama in verse) by J. Chester Johnson Copyright © 2015 by J. Chester Johnson 1 Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Germany’s Jeremiah Born 1906 in Breslau, Germany (now, part of Poland) into a prominent, but not particularly religious family, Dietrich Bonhoeffer embraced the teachings of Protestantism early, becoming a well-known theologian and acclaimed writer while still in his twenties. When most of the Church leadership in Germany crumbled under the weight of Nazism, Bonhoeffer and a group of colleagues set about establishing the Confessing Church as a moral and spiritual counterforce. Bonhoeffer also plotted with a group of co-conspirators to overthrow Hitler; toward that end, he participated in organizing efforts to assassinate the Nazi leader. Arrested in April, 1943, Bonhoeffer remained in prison for the rest of his life. Remnants of the Hitler command were so obsessed with Bonhoeffer’s death that they executed him at the Flossenburg concentration camp, located near the Czechoslovakian border, on April 9, 1945, only two weeks before American liberation of the camp. Stripped of clothing, tortured and led naked to the gallows yard, he was then hanged from a tree. In 1930, Dietrich Bonhoeffer arrived here in New York City from Germany with a doctorate of theology and additional graduate work in hand and with some experience as a curate for a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona, Spain. He had been awarded a fellowship to Union Theological Seminary, where he came under the influence of many of the leading theological luminaries of the day, including Reinhold Niebuhr, a major force for social ethics. -

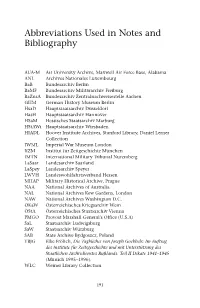

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Editor's Introduction to the English Edition

EDINTRO:EDINTRO.QXD 2/17/2009 10:29 AM Page 1 W AYNE W HITSON F LOYD, JR . EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH EDITION Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s name was introduced to the English-speaking world through the appreciative reception that was given to certain of his writings in the generation following the second world war. Titles such as The Cost of Discipleship, Life Together, Ethics, and Letters and Papers from Prison summoned an image of a courageous pastor and thoughtful the- ologian who rose above the confusion and inaction of his age not only to speak prophetic words of clarity but also to take costly actions of resis- tance against the horrors of National Socialism. His provocative words became a staple among those themselves searching for an adequate response to a ‘world come of age’ in the 1950s and 1960s. He evoked a fearless openness to the challenges of modernity, a way to be Christian without succumbing to mere religiosity, a spiritual path that led into the midst of this world, evoking a compassionate and redemptive embrace of both life’s gifts and its deep wounds and needs. Far less well known and read, however, were the works that come from the first half of Bonhoeffer’s adult life — the writings from the time of his academic preparation for an anticipated professional life as a univer- sity professor, as well as those that were the first fruits of his academic vocation. To be ignorant, however, of his first dissertation Sanctorum Communio,[1] or the university lectures later published as Creation and [1.] Sanctorum Communio was Bonhoeffer’s doctoral dissertation, the first of two theses that were required of a candidate wishing to receive a doctorate and to teach in a German university. -

Editor's Introduction to the Reader's Edition of Ethics

Editor’s Introduction to the Reader’s Edition of Ethics Clifford J. Green Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s has been called one of the greatest works Ethics of twentieth-century theology. Bonhoeffer regarded it as his major work, but he warns us that it is not what people might be looking for in a book on ethics. He begins with the outrageous demand that readers must give up the very questions that led them to a book on ethics: How can I be good, and how can I do good? Instead, he says, Christian ethics is about “God’s reality revealed in Christ becoming real among God’s creatures” (000; 6:47–49). This introduction explores what he means. It’s about a theological ethic of reality and responsibility. Bonhoeffer wrote his during the early part of World War Ethics II. He began in 1940 and wrote thirteen manuscripts before he was arrested and imprisoned in April 1943; these manuscripts have been printed as “chapters” in this book. Already in 1933 Bonhoeffer regarded the dictator Hitler not as a leader ( ), but a misleader, a Führer vii ETHICS tyrant. He opposed the militaristic nationalism of the new Germany, rooted in “blood and soil,” even as the German Evangelical Church and most of its leaders succumbed to the new ideology. By the early period of the war, the embrace of Nazi ideology at all levels of society had led to the complete corruption of social and personal ethical behavior among most Germans. Official murder, so-called “mercy killing,” was being carried out on physically and mentally disabled people who were classified as “life unworthy of life.” Invading German armies committed atrocities against civilians, especially on the Eastern Front. -

Responsibility for Future Generations (PDF)

THE POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CHURCH Responsibility for Future Generations PRIMING THE PUMP: When you think about the future the children of St. Andrew face, what fills you with foreboding? INTRODUCTION: “AFTER TEN YEARS” 1 1. Written at Christmas 1942, a few months prior to arrest on April 5, 1943 2. Addressed to co-conspirators a. Eberhard Bethge: student, confessing partner, and dear friend b. Hans von Dohnanyi: brother-in-law and mastermind of conspiracy c. Hans Oster: chief of Central Section in Military Intelligence Office 3. Included as Prologue in Letters and Papers from Prison a. Bridges gap between final months of freedom and imprisonment b. “New Year’s” reflection, taking stock of events of events and issues EXPOSING THE MASQUERADE OF EVIL 1. Nazis clothed themselves in “garb of relative historical and social justice” 2 2. In extreme situation like Nazi Germany may have to stand firm with truthful/responsible deeds rather than words 3. Failed attempts to stand firm a. Reasonable people: reason will fix things b. Fanatical people: attack evil with purity of principle c. People of conscience: torn apart by conflicting ethical factors d. Dutiful people: obey commands of those in authority e. People of freedom: value necessary deed more highly than untarnished conscience and reputation f. Privately virtuous: close eyes to injustices around them 4. Standing firm by engaging in responsible/truthful action a. Ultimate not reason, principles, conscience, duty, freedom, virtue b. Obedient and responsible action toward God and other humans c. Critiques any approach focused too exclusively on consequences, motives, or any one ethical factor d. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945.