Princess Iolanda Pensa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Download This PDF File

Podcasting as Activism and/or Entrepreneurship: Cooperative Networks, Publics and African Literary Production Madhu Krishnan; Kate Wallis University of Bristol; University of Exeter, UK In April 2017, we were present at a workshop titled “Personal Histories, Personal Archives, Alternative Print Cultures,” organized as part of the AHRC Research Network “Small Magazines, Literary Networks and Self-Fashioning in Africa and its Diasporas” (see Smit for a report on the session). The workshop was held at the now-defunct Long Street premises of Chimurenga, a self-described “project-based mutable object, publication, pan-African platform for editorial and curatorial work” based in Cape Town and best known for their eponymous magazine, which published sixteen issues between 2002 and 2011 (Chimurenga). As part of a conversation with collaborators Billy Kahora and Bongani Kona, editor Stacy Hardy was asked how Chimurenga sought out and forged readerships and publics. In her response, Hardy argued that the idea of a “target market” was “dangerous” and “arrogant,” offering a powerful repudiation to dominant models within the global publishing industry and book trade. Chimurenga, Hardy explained, worked from the premise articulated by founder Ntone Edjabe that “you don’t have to find readers, they find you.” Chimurenga’s ethos, Hardy explained, was one based on recognition, what she terms the “recognition of being part of something,” of “encountering Chimurenga and clocking into belonging” (Hardy, Kahora and Kona). Readers, for Hardy, were “Chimurenga people” who would find the publication and, on finding it, find something of themselves within it, be it through engagement with the magazine, attendance at Chimurenga’s live events and parties, or participation in the collective’s online presence. -

Bili Bidjocka. the Last Supper • Simon Njami, Bili Bidjocka

SOMMAIRE OFF DE DAPPER Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau ............................................................................. 6 SOLY CISSÉ. Lecture d’œuvre/Salimata Diop ................................................................................... 13 ERNEST BRELEUR. Nos pas cherchent encore l’heure rouge/Michael Roch ...................................................... 19 Exposition : OFF de Dapper Fondation Dapper 5 mai - 3 juin 2018 JOËL MPAH DOOH. Commissaire : Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau Transparences/Simon Njami ....................................................................................... 25 Commissaire associée : Marème Malong Ouvrage édité sous la direction de Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau BILI BIDJOCKA. Contribution éditoriale : Nathalie Meyer The Last Supper/Simon Njami ................................................................................... 29 Conception graphique : Anne-Cécile Bobin JOANA CHOUMALI. Série « Nappy ! »/Olympe Lemut ................................................................................. 33 BEAUGRAFF & GUISO. L’art de peindre les maux de la société/Ibrahima Aliou Sow .......................................... 39 GABRIEL KEMZO MALOU. Le talent engagé d’un homme libre/Rose Samb ............................................................... 45 BIOGRAPHIES DES ARTISTES...................................................................... 50 BIOGRAPHIES DES AUTEURS...................................................................... 64 CAHIER PHOTOGRAPHIQUE. MONTAGE -

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value Doseline Wanjiru Kiguru Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Dr. Daniel Roux and Dr. Mathilda Slabbert Department of English Studies Stellenbosch University March 2016 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Signature…………….………….. Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedication To Dr. Mutuma Ruteere iii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates the centrality of international literary awards in African literary production with an emphasis on the Caine Prize for African Writing (CP) and the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (CWSSP). It acknowledges that the production of cultural value in any kind of setting is not always just a social process, but it is also always politicised and leaning towards the prevailing social power. The prize-winning short stories are highly influenced or dependent on the material conditions of the stories’ production and consumption. The content is shaped by the prize, its requirements, rules, and regulations as well as the politics associated with the specific prize. As James English (2005) asserts, “[t]here is no evading the social and political freight of a global award at a time when global markets determine more and more the fate of local symbolic economies” (298). -

Document De Présentation Exitour

Exit Tour EXITOUR EXITOUR est un projet itinérant qui a duré 2 mois entre les différentes capitales d’Afrique de l’Ouest réalisé en transport public par un groupe d’artistes contemporains camerounais. Le but de ce projet était celui de rencontrer les différentes scènes artistiques de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et d’initier un dialogue avec ses membres rencontrés. La Biennale de Dakar était supposée être la dernière étape de ce voyage après les différentes étapes des capitales : Cotonou, Lomé, Accra, Ouagadogou, Bamako, etc… Goddy Leye (artiste et manageur du projet) et deux jeunes artistes (Justine Gaga et LucFosther Diop) de Douala ont conçu ce projet qui est né du sentiment d’isolation dans lequel les artistes se sentaient dans leurs pays respectifs et du désir de rencontrer leurs homologues qui vivent dans des conditions socio-culturelles similaires et d’initier un réseau d’artistes de Afrique de l’Ouest. L’un des objectifs de Goddy Leye était celui de mettre en contact les artistes de l’Afrique de l’Est entre eux afin de conscientiser les jeunes artistes de l’importance que l’art peut avoir dans un contexte local, que ils ne ce concentrent pas trop ou seulement sur le marche en Europe. Il était également important pour eux de découvrir et de comprendre les différentes politiques culturelles de chaque pays, en essayant de donner une idée de la situation de l’art contemporain en Afrique de l’Ouest. Afin de faciliter la mise en contact au cours de son itinérance, EXITOUR a organisé des symposiums, des ateliers et des expositions dans chaque capitale et ses membres ont chaque fois pris le temps de visiter des institution et projet culturel. -

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing Maureen Amimo Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Louise Green Co-supervisor: Prof Grace Musila March 2020 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: ……………………………………… Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates contemporary travel narratives about Africa by Africans authors. Scholarship on travel writing about Africa has largely centred examples from the Global North, yet there is a rich body of travel writing by African authors. I approach African travel writing as an emerging genre that allows African authors to engage their marginality within the genre and initiate a transformative poetics inscribing alternative politics as viable forms of meaning-making. I argue that contemporary African travel writing stretches and redefines the aesthetic limits of the genre through experimentation which enables the form to carry the weight and complexities of African experiences. Drawing on the work of theorists such as Edward Said, Mary Louise Pratt, James Clifford and Syed Manzurul Islam, as well as local philosophy emergent from the texts, I examine the reimaginations of the form of the travel narrative, which centre African experiences. -

Izibongo Issue 62

IZIBONGO Celebrating Art in Africa and the Diaspora Issue 62 - 2018 Universal Quest a review of Visual Arts in Cameroon: A Genealogy of Non-Formal Training 1976-2014 by Annette Schemmel Natty Mark Samuels Editorial As well as a review of Visual Arts in Cameroon, this issue also contains a tribute to the Bamum drawings, which I call Njoyism. Alongside the text I've placed some artwork, to give you an opportunity to view the work of some of the artists mentioned in the book and in the review. Two Cameroonian artists have already been celebrated in this magazine; Angu Walters (issue 11) and Nzante Spee (issue 56). Future issues will feature Pascal Kenfack, Aziseh Emmanual and Napolean Bongaman. In this celebration of Cameroon, I am happy to present to you, Universal Quest and A Source of Light. Editor – Natty Mark Samuels – africanschool.weebly.com – An African School Production Front cover photograph - Pascal Kenfack sculpting – from Wikipedia Universal Quest©Natty Mark Samuels, 2018. A Source of Light©Natty Mark Samuels, 2018. Koko Komegne from Alchetron https://reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/izibongo-magazine-2018.html http://rastaites.com/izibongo-issues-49-56/ from African Books Collective Koko Komegne from Away from Africa Indignation - from Biennale de Dakar Justine Gaga – from Intense Art Magazine Chemin de Croix (Path of the Cross) III Engelbert Mveng Chemin de Croix (Path of the Cross) XII Engelbert Mveng Both paintings from Pinterest Engelbert Mveng from Twitter Universal Quest I have to confess that before reading this, I could only name three Cameroonian artists: Azante Spee, Angu Walters and Napoleon Bongaman. -

+| Download the Pdf Version

“Embracing Opacity” Interview with Ntone Edjabe (Chimurenga Magazine) Ntone Edjabe is the founder and editor of Chimurenga, a literary magazine produced in Cape Town focusing on contemporary African politics and popular culture. The title Chimurenga refers to the Shona word for ‘struggle’ as well as to a popular music genre in Zimbabwe. In this conversation on July 14th 2011, Edjabe looks back at the first decade of publishing Chimurenga and speaks about the philosophy underlying the publication. His current project, The Chimurenga Chronicle, takes on the form of a newspaper backdated to the week of May 11 – 18 2008, the period marked by the outbreak of so-called xenophobic violence in South Africa. In an effort to shift the perspective away from the confines of nation-states The Chimurenga Chronicle is produced in cooperation with independent publishers Kwani? in Kenya and Nigeria’s Cassava Republic Press. The newspaper will be released on October 19th 2011, the day known in South Africa as “Black Wednesday” since the historic day in 1977 when the apartheid regime declared 19 Black Consciousness organisations illegal and banned two newspapers. Subtitled “A speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present”, The Chimurenga Chronicle engages with the call of theorist Achille Mbembe, to “imagine new forms of mobilization and leadership, to create an ‘intellectual plus-value’ based on a ‘concept-of-what-will-come’”. The first edition of Chimurenga was published in 2002. Approaching your 10th anniversary as a literary magazine, what are some of the changes and continuities characterising the Chimurenga publication? There was no clear strategy behind the project in the beginning, and I think that is perhaps one of the reasons why we are still here. -

A Pan-African Space in Cape Town? the Chimurenga Archive of Pan-African Festivals

Journal of African Cultural Studies ISSN: 1369-6815 (Print) 1469-9346 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjac20 A Pan-African space in Cape Town? The Chimurenga archive of Pan-African festivals Alice Aterianus-Owanga To cite this article: Alice Aterianus-Owanga (2019): A Pan-African space in Cape Town? The Chimurenga archive of Pan-African festivals, Journal of African Cultural Studies, DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2019.1632696 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2019.1632696 Published online: 23 Aug 2019. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjac20 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN CULTURAL STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2019.1632696 A Pan-African space in Cape Town? The Chimurenga archive of Pan-African festivals Alice Aterianus-Owanga Institut de sciences sociales des religions, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Created in 2002 in Cape Town by Ntone Edjabe, Chimurenga is a Pan-Africanism; archives; multidimensional project that combines a print magazine, a festivals; FESTAC; memory; workspace, a platform for editorial and curatorial activities, an Cape Town; South Africa; online library, and a radio station (the Pan-African Space Station). Chimurenga Based on collaborative ethnographic research with the Chimurenga team, this paper discusses the collection, production and creation of an archive about Pan-African festivals that this collective has developed through their cultural activities. After a brief overview of Festival of Black Arts and Culture (FESTAC) which took place in Lagos in 1977, and the history of Pan-African festivals, I describe the materials collected by Chimurenga and the projects in which they have participated. -

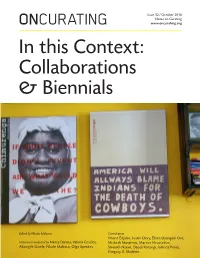

In This Context: Collaborations & Biennials

Issue 32 / October 2016 Notes on Curating ONCURATING www.oncurating.org In this Context: Collaborations & Biennials Edited by Nkule Mabaso Contributors Ntone Edjabe, Justin Davy, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Interviews conducted by Nancy Dantas, Valeria Geselev, Misheck Masamvu, Marcus Neustetter, Abongile Gwele, Nkule Mabaso, Olga Speakes Smooth Nzewi, Daudi Karungi, Iolanda Pensa, Gregory G. Sholette Contents 02 Editorial Nkule Mabaso INTERVIEWS ON COLLABORATIONS INTERVIEWS ON BIENNIALS 09 55 Ntone Edjabe of Chimurenga Smooth Nzewi interviewed by Valeria Geselev interviewed by Nkule Mabaso 13 62 Justin Davy of Burning Museum Daudi Karungi interviewed by Nancy Dantas interviewed by Nkule Mabaso 19 65 Gregory Sholette Misheck Masamvu interviewed by Nkule Mabaso interviewed by Olga Speakes 24 Marcus Neustetter of On Air 70 interviewed by Abongile Gwele Imprint PAPERS 33 Counting On Your Collective Silence by Gregory G. Sholette 43 For Whom Are Biennials Organized? by Elvira Dyangani Ose 48 Public Art and Urban Change in Douala by Iolanda Pensa Editorial In this Context: Collaborations & Biennials Editorial Nkule Mabaso This issue of OnCurating consists of two parts: the first part researches collaborative work with an emphasis on African collectives, and the second part offers an insight into the development of biennials on the African continent. Part 1 Collaboration Is collaboration an inherently ‘better’ method, producing ‘better’ results? The curatorial collective claims that the purpose of collaboration lies in producing something that would -

Biennial Culture Or Grassroots Globalisation? The

Patrick B. Mudekereza 130 55 34 Master in History of Art (full time) Research Report Title: Biennial Culture or Grassroots Globalisation? The challenge of the Picha art centre, as a tool for building local relevance for the Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi. Supervisor: Nontobeko Ntombela Abstract: This research aims to examine how the organisation of a biennial and its content could influence the modelling of an independent art centre. Using the concept coined by Arjun Appadurai, ‘grassroots globalisation’, this research unpacks the establishment of Picha art centre through its project Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi (2010-2013), a case study, in examining how specificities of the global south geopolitics may encourage alternative art institutions to emerge. By studying the first three years of Picha through the project Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi (2010-2013), this research investigates how the art centre was created as a tool to position the organisation within the global art discourse whilst maintaining its local relevance in Lubumbashi. It is located at the intersection of three areas of study: Biennial culture, alternative institution models, and global South strategies and politics. 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter I: HISTORICAL -

Writing About! ~In Selfless Service to Our Community~ ~In Selfless Service to Our Community~ in Selfless Ser

FUCKING GOOD ART#25 Writing about! ~in selfless service to our community~ ~in selfless service to our community~ in selfless ser Editorial first week comprised a hectic Good evening, I’m Patrick Mefang // Public art or art in public spaces? schedule of visits to art insti- Writing about tutions and cultural funding // Never swallow the past // Cultural context of Douala // Editorial: 3 Talking About! bodies. Interspersed amongst Writing About Talking About // Art and gentrification: a problematic these visits were several public infatuation // Interview with Goddy Leye // Wine and smoke on the Lucia Babina and Zoë Gray or semi-public events, which enabled us to broaden the water // Cultural context of Douala // What happens when we conversation to include ad- 4 make time to talk with our ditional interlocutors. For peers from another coun- the second week, each of our try, from another continent, guests worked together with a from another cultural context host, a carefully chosen artist, altogether? For the project collective or institution who Talking About!, we invited six had been “match-made” with artists and cultural practition- our guests. Achille Atina Tah ers from Douala (Cameroon) worked with me [Zoë Gray] to travel to Rotterdam in at Witte de With; Ruth September 2009 to gain Belinga with Annie Fletcher an overview of the Dutch and Charles Esche at the contemporary art scene. Part Van Abbemuseum; Goddy workshop, part tour, Talking Leye and Hervé Youmbi with About! was primarily a peer- Kim Bouvy & Elian Somers to-peer exchange, a sequence at Het Wilde Weten, with of conversations between our David Maroto (Duende), and Cameroonian guests and their me [Lucia Babina] of iStrike; Dutch counterparts.