0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICES of the CREATIVE PROCESS Ways of Learning and Teaching Film and Audiovisual Art

PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICES OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS Ways of learning and teaching film and audiovisual art Alain Bergala revolutionized how the art of filmmaking is taught through the concept of a "pedagogy of the creative process". Considering the widespread practice of what had been called "audiovisual literacy", that is, the acquisition of knowledge on the use of audiovisual language, Bergala advocated for a more active form of teaching, one in which viewers would have to return to that time prior to the images and the sounds, when all possibilities were still open. The paradigm shift introduced the notion that the viewer's motivation, emotion and desire could be a driving force behind learning and the possibility that viewers might potentially become creators. The seminar "Pedagogy of the creative process" aims to serve as a space for meeting and reflecting on how film and audiovisual art is taught, the starting point for which will be covered in the first session: the paradigm shift first introduced by Bergala for teaching cinema in schools. The second session will be a reflection on the role of film schools and universities in teaching cinema, from the point of view of theory and practice. In this regard, the recently inaugurated school, the Elías Querejeta Zine Eskola, marks a pivotal moment in its break with prototypical schools that typically have taken a 20th century approach to film, one being called into question today. Any reflection on teaching the creative process would hardly be complete without a consideration of the interconnections that teaching audiovisuals has made with the social sciences and critical teaching methods. -

Hamilton Easter Fiel

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Contents Curating Film

Issue # 03/10 : Curating Film Freely distributed, non - commercial, digital publication an artwork. The sound track (where it exists) often clashes in a disturbing manner with the other works on view in the same room. The typical cinema ar- rangement, consisting of a dark room, a film, a projection, and the audience, is so closely associated with the act of watching a film that is virtually seems like a must, and, unsur- prisingly, large, international art institutions are increas- ingly having their own cinemas built for the purpose of showing these works. The distinguished media theorist Christian Metz associates the space of the imagination, the space of pro- jection, with the present economic order: “It has often rightly been claimed that cinema is a technique of the imagin- ation. On the other hand, this technique is characteristic of a historical epoch (that of capitalism) and the state of a society, the so-called indus- trial society.”1 Scopophilia (pleasure in looking) and voyeurism are deeply inscribed in our society; in a cinema, the audience is placed at a voyeuristic distance and can unashamedly satisfy his cur- iosity. Passiveness, a play with identifications and a CONTENTS CURATING consumption-oriented attitude constitute the movie-watchers’ 01 Introduction position. Laura Mulvey moreover FILM calls attention to the fact that 02 The Cinema Auditorium the visual appetite is as much Interview with Ian White dominated by gender inequality as the system we live in.2 Natu- 04 The Moving Image rally, (experimental) films and Interview with Katerina Gregos INTRODUCTION the various art settings in which they are presented can 07 Unreal Asia and will violate the conventions Interview with Gridthiya Gaweewong and David Teh Siri Peyer of mainstream cinema from case to case. -

Brazilian Films and Press Conference Brunch

rTh e Museum of Modern Art No. 90 FOR REL.EIASE* M VVest 53 street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart ^ ^ , o -, . ro ^ Wednesday^ October 2, i960 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART INTRODUCES BRAZILIAN FILMS In honor of Brazil's new cinema movement called Cinema NovO; The Museum of Modern Art will present a ten-day program of features and shorts that reflect the recent changes and growth of the film industry in that country. Cinema Novo: Brasil. the New Cinema of Brazil, begins October 1. and continues through I October 17th. Nine feature-length films;, the work of eight young directors; who represent the New Wave of Brazil^ will be shown along with a selection of short subjects. Adrienne Mancia, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, assembled the program. In the past seven years, the Brazilians have earned i+0 international awards. In Berlin, Genoa and Moscow. Brazilian film retrospectives have been held in acknowledgement of the vigorous Cinema Novo that has taken root in that country. Cinema Novo of Brazil has had a stormy history. The first stirring began in the early 50*8 with the discontent of young filmmakers who objected to imitative Hollywood musical comedies, known as "chanchadas," which dominated traditional Brazilian cinema. This protest found a response araong young film critics who were inspired by Italian neo- realism and other foreign influences to demand a cinema indigenous to Brazil. A bandful of young directors were determined to discover a cinematic language that would reflect the nation's social and human problems. The leading exponent of Cinema Novo, Glauber Rocha, in his late twenties, stated the commitLment of Brazil's youthful cineastes when he wrote: "In our society everything is still I to be done: opening roads through the forest, populating the desert, educating the masses, harnessing the rivers. -

Ebook Download the Cinema of Russia and the Former Soviet

THE CINEMA OF RUSSIA AND THE FORMER SOVIET UNION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Birgit Beumers | 288 pages | 30 Apr 2007 | WALLFLOWER PRESS | 9781904764984 | English | London, United Kingdom The Cinema of Russia and the Former Soviet Union PDF Book However, different periods of Soviet cinema have been covered quite unevenly in scholarship. Greenland is not a country. The result is an extraordinary, courageous work of documentary-making, austere yet emotive, which records soup distribution and riots alike with the same steady, unblinking gaze. Username Please enter your Username. Take Elem Klimov. Bill Martin Jr.. Even though it was wrecked by political unrest, the Russian economy continued to grow over the years. It offers an insight into the development of Soviet film, from 'the most important of all arts' as a propaganda tool to a means of entertainment in the Stalin era, from the rise of its 'dissident' art-house cinema in the s through the glasnost era with its broken taboos to recent Russian blockbusters. Votes: 83, Yet they still fail to make a splash outside of their native country. The volume also covers a range of national film industries of the former Soviet Union in chapters on the greatest films and directors of Ukrainian, Kazakh, Georgian and Armenian cinematography. Seven natural wonders. Article Contents. History of film Article Media Additional Info. Olympic hockey team to victory over the seemingly invincible Soviet squad. While Soviet and Russian cinema was rather understudied until the collapse of the USSR, since the early s there has been a rise in publications and scholarship on the topic, reflecting an increase in the popularity of film and cultural studies in general. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Gellner differentiates nations from states and holds that both can emerge independent of each other. See Gellner, E. 2008. Nations and Nationalism. New York: Cornell University Press. 2. During the inter-war period and war years documentary was used for propa- gandist purposes to shape favourable public opinion towards the war. Leni Riefenstahl’s spectacular representations of Germany around the time of the Nazi ascendance to power, and Britain’s charged propaganda documentaries during the war both come to mind here. Propagandist documentary has also been mobilized to celebrate national development and planning pro- grammes, for example, Dziga Vertov’s dynamic representations of the Soviet Union’s five-year plans through his kino-pravda series and other full-length documentaries. The vast body of investigative, activist and exposé documen- taries has questioned nations, their institutions and ideological discourses. 3. Corner, J. 1996. The Art of Record: A Critical Introduction to Documentary. New York: Manchester University Press. 4. I take my cue here from Noel Carroll who, while discussing objectivity in relation to the non-fiction film, argues that documentary debate has been marred by con- fusions in the use of language that conflate objectivity with truth (Carroll 1983: 14). While I agree with Carroll that lack of objectivity does not necessarily mean bias, as a practitioner I am inclined to hold documentary making and reception as subjective experiences exercising subjects’, makers’ and the audiences’ ideo- logical stances, knowledge systems and even aesthetic preferences. 5. Governmental and semi-governmental funding bodies such as Prasar Bharati (Broadcasting Corporation of India), Public Service Broadcasting Trust and the Indian Foundation for the Arts offer financial support for documentary makers and Indian filmmakers have also secured funding from international agencies such as the European Union’s cultural funds. -

Bili Bidjocka. the Last Supper • Simon Njami, Bili Bidjocka

SOMMAIRE OFF DE DAPPER Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau ............................................................................. 6 SOLY CISSÉ. Lecture d’œuvre/Salimata Diop ................................................................................... 13 ERNEST BRELEUR. Nos pas cherchent encore l’heure rouge/Michael Roch ...................................................... 19 Exposition : OFF de Dapper Fondation Dapper 5 mai - 3 juin 2018 JOËL MPAH DOOH. Commissaire : Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau Transparences/Simon Njami ....................................................................................... 25 Commissaire associée : Marème Malong Ouvrage édité sous la direction de Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau BILI BIDJOCKA. Contribution éditoriale : Nathalie Meyer The Last Supper/Simon Njami ................................................................................... 29 Conception graphique : Anne-Cécile Bobin JOANA CHOUMALI. Série « Nappy ! »/Olympe Lemut ................................................................................. 33 BEAUGRAFF & GUISO. L’art de peindre les maux de la société/Ibrahima Aliou Sow .......................................... 39 GABRIEL KEMZO MALOU. Le talent engagé d’un homme libre/Rose Samb ............................................................... 45 BIOGRAPHIES DES ARTISTES...................................................................... 50 BIOGRAPHIES DES AUTEURS...................................................................... 64 CAHIER PHOTOGRAPHIQUE. MONTAGE -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

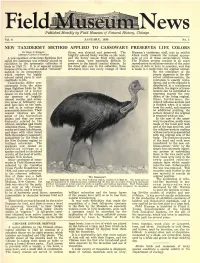

New Taxidermy Method Applied to Cassowary Preserves Life Colors

News Pvblished Monthly by Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Vol. 6 JANUARY, 1935 No. 1 NEW TAXIDERMY METHOD APPLIED TO CASSOWARY PRESERVES LIFE COLORS By Karl P. Schmidt River, was skinned and preserved. The Museum's taxidermy staff, into an exhibit Assistant Curator of Reptiles brightly colored fleshy wattles on the neck, which really presents the natural appear- A new specimen of the large flightless bird and the horny casque filled with spongy ance of one of these extraordinary birds. called the cassowary was recently placed on bony tissue, were especially difficult to The Walters process consists in an exact exhibition in the systematic collection of preserve in the humid tropical climate. In reproduction in cellulose-acetate of the outer birds in Hall 21. It is of especial interest the dried skin now in the collection, these layers of skin or horn in question, and this because of the use of the so-called "celluloid" structures have lost every vestige of their is made in a mold from the original animal. method in its preparation By the admixture of the which renders its highly proper pigments in the dis- colored naked parts in veri- solved cellulose-acetate, the similitude to life. coloration is exactly repro- Cassowaries differ con- duced, and as the pigment is spicuously from the other distributed in a translucent large flightless birds by the medium, the degree of trans- development of a horny lucence can be controlled to casque on the head, and by represent exactly the con- the presence of brightly dition of the living original. -

Credit Exclusions, Repeatability, Concentration Exclusions

Credit Exclusions, Repeatability, Concentration Exclusions 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 103. First Year Social Science Seminar. 247(448) / Hist. 247. Africa Since 1850. (Cross-Area Courses). May not be included in a concentration plan. (African Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 104. First Year Humanities Seminar. 274 / Engl. 274. Introduction to Afro-American Literature. (Cross-Area Courses). May not be included in a concentration plan. (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 108 / Hist. of Art 108. Introduction to African Art. 303 / Soc. 303. Race and Ethnic Relations. (African Studies). May not be included in a concentration plan. (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 111. Introduction to Africa and Its Diaspora. 321 / Soc. 323. African American Social Thought. May not be included in a concentration plan. (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 200(105). Introduction to African Studies. 322 / NR&E 335. Introduction to Environmental Politics: Race, Class, and Gender. (African Studies). (Cross-Area Courses). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 201(100). Introduction to Afro-American Studies. 325. Afro-American Social Institutions. (African-American Studies). (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 202(200). Introduction to Afro-Caribbean Studies. 326. The Black American Family. (Afro-Caribbean Studies). (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 203. Issues in Afro-American Development. 327 / Psych. 315. Psychological Aspects of the Black Experience. (African-American Studies). (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 204. Cultural History of Afro-America. 329. African American Leadership. (African-American Studies). (African-American Studies). 311 CAAS 311 CAAS 205. Introduction to Black Cultural Arts and Performance. 330. African Leaders. May be elected for credit twice. -

Industry Guide Focus Asia & Ttb / April 29Th - May 3Rd Ideazione E Realizzazione Organization

INDUSTRY GUIDE FOCUS ASIA & TTB / APRIL 29TH - MAY 3RD IDEAZIONE E REALIZZAZIONE ORGANIZATION CON / WITH CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI / WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON / IN COLLABORATION WITH CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI / WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF CON IL PATROCINIO DI / UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF FOCUS ASIA CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORAZIONE CON/WITH COLLABORATION WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PROJECT MARKET PARTNERS TIES THAT BIND CON IL SUPPORTO DI/WITH THE SUPPORT OF CAMPUS CON LA PARTECIPAZIONE DI/WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF MAIN SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS FESTIVAL PARTNERS TECHNICAL PARTNERS ® MAIN MEDIA PARTNERS MEDIA PARTNERS CON / WITH FOCUS ASIA April 30/May 2, 2019 – Udine After the big success of the last edition, the Far East Film Festival is thrilled to welcome to Udine more than 200 international industry professionals taking part in FOCUS ASIA 2019! This year again, the programme will include a large number of events meant to foster professional and artistic exchanges between Asia and Europe. The All Genres Project Market will present 15 exciting projects in development coming from 10 different countries. The final line up will feature a large variety of genres and a great diversity of profiles of directors and producers, proving one of the main goals of the platform: to explore both the present and future generation of filmmakers from both continents. For the first time the market will include a Chinese focus, exposing 6 titles coming from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Thanks to the partnership with Trieste Science+Fiction Festival and European Film Promotion, Focus Asia 2019 will host the section Get Ready for Cannes offering to 12 international sales agents the chance to introduce their most recent line up to more than 40 buyers from Asia, Europe and North America. -

Women in East Asian Cinema a Chinese Film Forum UK Conference HOME, Manchester 4

Women in East Asian Cinema A Chinese Film Forum UK Conference HOME, Manchester 4 – 6 December, 2019 Recent interventions into global film and processes of canonisation have worked to highlight the contributions of women in spaces and discourses previously dominated by men. Yet, despite these social and academic movements, women remain under-represented across vital areas of film culture as recent discussions of the 2019 Oscars and the 2018 Cannes Film Festival have shown. This event aims to highlight the increasing English-language research of contributions by self-identifying women in East Asian cinema and to interrogate questions of representation, labour, and production contexts. For English speaking fans, academics and researchers based outside of East Asia, this work is all the more important as a counter to the limiting and selective problems of international film festivals and regional distribution. This three-day conference seeks to bring together researchers of women in East Asian cinema for a mix of panels, workshops, and film events with industry guests to continue and develop these ongoing conversations. The event is hosted as a collaboration between the Chinese Film Forum UK (CFFUK), a Manchester-based collective, and HOME, Manchester's leading independent cross-art venue and cinema. 2019 marks ten years since ‘Visible Secrets: Hong Kong's Women Filmmakers’: a film season that was organised by a nascent CFFUK at HOME's old Cornerhouse venue. This year also marks HOME's year-long programming initiative ‘Celebrating Women in Global Cinema’ which continues the celebratory, research-led and consciousness raising work of that original Visible Secrets project.