Izibongo Issue 62

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Bili Bidjocka. the Last Supper • Simon Njami, Bili Bidjocka

SOMMAIRE OFF DE DAPPER Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau ............................................................................. 6 SOLY CISSÉ. Lecture d’œuvre/Salimata Diop ................................................................................... 13 ERNEST BRELEUR. Nos pas cherchent encore l’heure rouge/Michael Roch ...................................................... 19 Exposition : OFF de Dapper Fondation Dapper 5 mai - 3 juin 2018 JOËL MPAH DOOH. Commissaire : Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau Transparences/Simon Njami ....................................................................................... 25 Commissaire associée : Marème Malong Ouvrage édité sous la direction de Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau BILI BIDJOCKA. Contribution éditoriale : Nathalie Meyer The Last Supper/Simon Njami ................................................................................... 29 Conception graphique : Anne-Cécile Bobin JOANA CHOUMALI. Série « Nappy ! »/Olympe Lemut ................................................................................. 33 BEAUGRAFF & GUISO. L’art de peindre les maux de la société/Ibrahima Aliou Sow .......................................... 39 GABRIEL KEMZO MALOU. Le talent engagé d’un homme libre/Rose Samb ............................................................... 45 BIOGRAPHIES DES ARTISTES...................................................................... 50 BIOGRAPHIES DES AUTEURS...................................................................... 64 CAHIER PHOTOGRAPHIQUE. MONTAGE -

Document De Présentation Exitour

Exit Tour EXITOUR EXITOUR est un projet itinérant qui a duré 2 mois entre les différentes capitales d’Afrique de l’Ouest réalisé en transport public par un groupe d’artistes contemporains camerounais. Le but de ce projet était celui de rencontrer les différentes scènes artistiques de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et d’initier un dialogue avec ses membres rencontrés. La Biennale de Dakar était supposée être la dernière étape de ce voyage après les différentes étapes des capitales : Cotonou, Lomé, Accra, Ouagadogou, Bamako, etc… Goddy Leye (artiste et manageur du projet) et deux jeunes artistes (Justine Gaga et LucFosther Diop) de Douala ont conçu ce projet qui est né du sentiment d’isolation dans lequel les artistes se sentaient dans leurs pays respectifs et du désir de rencontrer leurs homologues qui vivent dans des conditions socio-culturelles similaires et d’initier un réseau d’artistes de Afrique de l’Ouest. L’un des objectifs de Goddy Leye était celui de mettre en contact les artistes de l’Afrique de l’Est entre eux afin de conscientiser les jeunes artistes de l’importance que l’art peut avoir dans un contexte local, que ils ne ce concentrent pas trop ou seulement sur le marche en Europe. Il était également important pour eux de découvrir et de comprendre les différentes politiques culturelles de chaque pays, en essayant de donner une idée de la situation de l’art contemporain en Afrique de l’Ouest. Afin de faciliter la mise en contact au cours de son itinérance, EXITOUR a organisé des symposiums, des ateliers et des expositions dans chaque capitale et ses membres ont chaque fois pris le temps de visiter des institution et projet culturel. -

Biennial Culture Or Grassroots Globalisation? The

Patrick B. Mudekereza 130 55 34 Master in History of Art (full time) Research Report Title: Biennial Culture or Grassroots Globalisation? The challenge of the Picha art centre, as a tool for building local relevance for the Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi. Supervisor: Nontobeko Ntombela Abstract: This research aims to examine how the organisation of a biennial and its content could influence the modelling of an independent art centre. Using the concept coined by Arjun Appadurai, ‘grassroots globalisation’, this research unpacks the establishment of Picha art centre through its project Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi (2010-2013), a case study, in examining how specificities of the global south geopolitics may encourage alternative art institutions to emerge. By studying the first three years of Picha through the project Rencontres Picha, Biennale de Lubumbashi (2010-2013), this research investigates how the art centre was created as a tool to position the organisation within the global art discourse whilst maintaining its local relevance in Lubumbashi. It is located at the intersection of three areas of study: Biennial culture, alternative institution models, and global South strategies and politics. 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter I: HISTORICAL -

Writing About! ~In Selfless Service to Our Community~ ~In Selfless Service to Our Community~ in Selfless Ser

FUCKING GOOD ART#25 Writing about! ~in selfless service to our community~ ~in selfless service to our community~ in selfless ser Editorial first week comprised a hectic Good evening, I’m Patrick Mefang // Public art or art in public spaces? schedule of visits to art insti- Writing about tutions and cultural funding // Never swallow the past // Cultural context of Douala // Editorial: 3 Talking About! bodies. Interspersed amongst Writing About Talking About // Art and gentrification: a problematic these visits were several public infatuation // Interview with Goddy Leye // Wine and smoke on the Lucia Babina and Zoë Gray or semi-public events, which enabled us to broaden the water // Cultural context of Douala // What happens when we conversation to include ad- 4 make time to talk with our ditional interlocutors. For peers from another coun- the second week, each of our try, from another continent, guests worked together with a from another cultural context host, a carefully chosen artist, altogether? For the project collective or institution who Talking About!, we invited six had been “match-made” with artists and cultural practition- our guests. Achille Atina Tah ers from Douala (Cameroon) worked with me [Zoë Gray] to travel to Rotterdam in at Witte de With; Ruth September 2009 to gain Belinga with Annie Fletcher an overview of the Dutch and Charles Esche at the contemporary art scene. Part Van Abbemuseum; Goddy workshop, part tour, Talking Leye and Hervé Youmbi with About! was primarily a peer- Kim Bouvy & Elian Somers to-peer exchange, a sequence at Het Wilde Weten, with of conversations between our David Maroto (Duende), and Cameroonian guests and their me [Lucia Babina] of iStrike; Dutch counterparts. -

Art. Contemporary. African

art. contemporary. Edition 1 Featuring: african. Odili Donald Odita, Otobong Nkanga, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Simon Njami, Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Riason Naidoo, Chimurenga. (Re-) Mapping the field: a bird’s eye view on discourses. IMPRINT / IMPRESSUM SAVVY | art.contemporary.african. SAVVY | kunst.zeitgenössisch.afrikanisch. Online magazine / Onlinezeitschrift Editor-in-chief / Project Initiator Chefredakteur / Projektinitiator Dr. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Deputy Editor-in-chief Stellv. Chefredakteurin Andrea Heister Editors of edition 1 Editoren von Ausgabe 1 Andrea Heister, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Proofreading for edition 1 Lektorat von Ausgabe 1 Katja Vobiller, Simone Kraft, Andrea Heister, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung Authors of edition 1 Autoren von Ausgabe 1 Aicha Diallo, Brenda Cooper, Andrea Heister, Prune Helfter, Nancy Hoffmann, Missla Libsekal, Alanna Lockward, Riason Naidoo, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Simon Njami, Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Annette Schemmel, Fiona Siegenthaler, Kangsen Feka Wakai Translations Übersetzungen Katja Vobiller, Claudia Lamas Cornejo, Johanna Ndikung, Simone Kraft, Andrea Heister Web design Webdesign Alice Motanga Graphic design Grafikdesign Soavina Ramaroson Bureau Büro Richardstr. 43/44 12055 Berlin Germany 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 0. Editorial Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung 1. Spotlight on... Go tell it on the mountain Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung / Andrea Heister A Maestro kicks the bucket: an obituary on Malangatana Der Vorhang fällt: ein Nachruf auf Malangatana Andrea Heister Wangechi Mutu passes the courvoisier to Yto Barrada Wangechi Mutu reicht den Courvoisier an Yto Barrada Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung House of African Art: First African Art Space in Asia House of African Art: erstes Haus für afrikanische Kunst in Asien Prune Helfter Goddy Leye is dead Goddy Leye ist tot Annette Schemmel 2. -

Gabi Ngcobo & Elvira Dyangani

www.sternberg-press.com visible where art leaves its own field and becomes visible as part of something else a project by Cittadellarte–Fondazione Pistoletto and Fondazione Zegna a book edited by Angelika Burtscher and Judith Wielander Publisher: Sternberg Press © 2010 the editors, the authors, Sternberg Press All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. ISBN 978-1-934105-09-2 Translation: Fang Hu, “New Species of Spaces” translated from the Chinese by Hsiao Hwei Yu, and from Italian to English by Simon Turner Copy editing: Courtney Johnson Graphic design: Studio Lupo & Burtscher, Bolzano, Italy Printing and binding: Agit Mariogros s.r.l., Turin, Italy Acknowledgements: Special thanks to the authors, artists, and curators who have contributed to visible. Thanks are also due to Luigi Coppola and Daniele Lupo. Cittadellarte–Fondazione Pistoletto via Serralunga 27, I-13900 Biella www.cittadellarte.it Fondazione Zegna via Marconi 23, I-13835 Trivero www.fondazionezegna.org Sternberg Press Caroline Schneider Karl-Marx-Allee 78, D-10243 Berlin 1182 Broadway #1602, New York, NY 10001 www.sternberg-press.com 1 visible where art leaves its own field and becomes visible as part of something else a project by Cittadellarte–Fondazione Pistoletto and Fondazione Zegna edited by Angelika Burtscher and Judith Wielander 3 6 Angelika Burtscher and Judith Wielander visible—where art leaves its own field and becomes visible as part of something else 10 Judith Wielander visible: An Interview With Michelangelo Pistoletto 18 Saskia Sassen Nomadic Territories and Times 28 Raimundas Malašauskas A Few Notes on Being Invisible and Visible at the Same Time 32 Pedro Reyes Baby Marx 38 Patrick Bernier + Olive Martin X and Y v. -

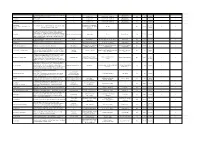

Bibliothèque Le Cube.Xlsx

titre de l'exposition artistes curateurs auteurs lieu de l'exposition éditeurs nombre de pages année langue exposition d'artistes marocains nombre d'exemplaires Fouad Bellamine, Mahi Binebine, Mustapha Boujemaoui, James Brown, Villa Delaporte / / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français x 1 Safâa Erruas, Sâad Hassani, Aziz Lazrak art contemporains Villa Delaporte Après la pluie Pierre Gangloff / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 52p 2011 français 1 art contemporains Villa Delaporte Jacques Barry Angel For Ever / Bernard Collet Villa Delaporte - Casablanca 48p 2009 français 1 art contemporains Yusur-Puentes Programmation culturelle de la Emilia Hernández Pezzi, Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya, Ainhoa Díez de Pablo, espagnol - Paysage et architecture au Maroc et en Présidence espagnole de l’Union Madrid 62p 2010 x 1 El Montacir Bensaïd, Iman Benkirane. français Espagne européenne Chourouk Hriech, Fouad Bellamine, Azzedine Baddou, Hassan Darsi, Ymane Fakhir, Faisal Samra, Fatiha Zemmouri, Mohamed Arejdal, Mohamed El Baz, Philippe Délis, Saad Tazi, Younes Baba Ali, Amande In, Between Walls Abdelmalek Alaoui, Yasmina Naji Yasmina Naji Rabat Integral Editions 44p 2012 français x 1 Anna Raimondo, Mohammed Fettaka, Ymane Fakhir, Mustapha Akrim, Hassan Ajjaj, Hassan Slaoui, Mohamed Laouli, Mounat Charrat, Tarik Oualalou, Fadila El Gadi Mohamed Abdel Benyaich, Hassan Darsi, Mounir Fatmi, Younes Regards Nomades Anne Dary Frédéric Bouglé Musée des Beaux Arts de Dole - France Ville de Dole 42p 1999 français x 1 Rahmoun, Batoul -

La Biennale De Dakar Comme Projet De Coopération Et De Développement

Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales en cotutelle avec Politecnico di Milano, Dipartimento di Architettura e Pianificazione Thèse de doctorat en Anthropologie sociale et ethnologie Governo e progettazione del territorio La Biennale de Dakar comme projet de coopération et de développement Candidat : Iolanda Pensa Directeurs de recherche Jean-Loup Amselle en cotutelle avec Rossella Salerno Jury Jean-Loup Amselle, Elio Grazioli, Rossella Salerno, Tobias Wendl Paris, 27 juin 2011 Iolanda Pensa, La Biennale de Dakar comme projet de coopération et de développement, 2011 [email protected] Pour texte et images de l'auteur Paternité-Partage des Conditions Initiales à l'Identique © Les auteurs et les artistes pour leurs images Font Gentium Basic 1.1 Victor Gaultney, 03/04/2008 © SIL Open Font License 1.1, 26/02/2006 Sommaire 5 Préface 7 Introduction 1. Objectifs et motivations scientifiques 8 – 2. Méthodologie et sources 10 – 3. Structure 12. 15 I. La Biennale de Venise 1. Le modèle historique de la Biennale de Venise 16 – 2. La première Biennale d'art de Dakar et le modèle de Venise 19 – 3. Ouverture et participation de l'Afrique à la Biennale de Venise 22 – 4. Le nouveau modèle de la Biennale de Dakar : Dak'Art devient une biennale d'art africain contemporain 31. 35 II. Les biennales africaines 1. Les caractéristiques des biennales 37 – 2. La Biennale du Caire 43 – 3. La Biennale de Cape Town 45 – 4. La Triennale de Luanda de 2007 58 – 5. La Triennale de Douala SUD- Salon Urbain de Douala 64. 75 III. Histoire de la Biennale de Dakar 1. -

Princess Iolanda Pensa

Princess Iolanda Pensa Dakar 2006 ‘Princess!’ shouts Jean-Charles. He slips off his chair, breaks into a smile and hurries into Marilyn’s arms. At the Dakar Biennial, in the Jazz Club Pen’Art, the musicians accompany the chatter and excitement as old friends meet up. Everyone’s cheerful, happy to be seeing each other after months, even years in some cases. Marilyn Douala Bell laughs. At Douala she’s Princess Marilyn Douala Bell, daughter of King Bell, a descendent of Rudolph Douala Manga Bell, hanged in 1914 for opposing German colonial rule, but among friends she’s just Marilyn. Jean-Charles’ princess is affectionately humorous. ‘My beautiful flower’, he seems to roguishly imply, with a deliberately retro tone, ‘we know you’re not just plain Marilyn’. Despite her many responsibilities, Princess Marilyn Douala Bell can spend this evening relaxing. She’s among friends; she can forget her official duties in the round of greetings. The table is crowded, Mamadou Jean-Charles Tall is seated halfway down it. An architect, brilliant and fair-minded, he has designed working-class housing, homes for the newly rich Senegalese, and the Elton service stations: structured like city squares and landmarks, they have become a model exported all over West Africa and are now being imitated by other oil companies. A few places down sits the anthropologist AbdouMaliq Simone. He has made seminal studies of the cities of Johannesburg and Douala, rich in narratives, encounters, and relationships. Sylviane Diop, cultural manager and promoter of the GAW digital art association, is seated beside her colleague N’Goné Fall, architect and curator. -

Douala À Ciel Ouvert / Douala Under an Open Sky

Document generated on 10/01/2021 11:40 a.m. Ciel variable Art, photo, médias, culture Douala à ciel ouvert Douala under an Open Sky Érika Nimis Strates Strata Number 101, Fall 2015 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/79816ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Productions Ciel variable ISSN 1711-7682 (print) 1923-8932 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Nimis, É. (2015). Douala à ciel ouvert / Douala under an Open Sky. Ciel variable, (101), 64–71. Tous droits réservés © Les Productions Ciel variable, 2015 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Douala à ciel ouvert Érika Nimis Douala1. Fin janvier 2015. Premiers pas dans les rues de cette ville portuaire, capitale économique du Cameroun. Douala est une ville qui vibre et vous échappe à tout moment. Premiers pas et déjà quelques repères. On ne peut parler de scène contemporaine à Douala sans parler de ses centres d’art qui lui donnent une iden- tité. Car à Douala, ville au passé trouble et au présent incertain, l’art est dans la rue où les artistes interviennent de façon concrète, comme en témoigne cette monumentale statue au rond-point Deïdo, La nouvelle liberté de Joseph-Francis Sumégné, commandi- Douala under an Open Sky tée en 1996 par le centre Doual’art et devenue depuis le symbole de la ville2. -

The City As Site: Building an Audience for Contemporary Art in Africa – Kerryn Greenberg in 2010, During a Conference at Tate

Higher Atlas / Au-delà de l’Atlas – The Marrakech Biennale [4] in Context The City as Site: Building an Audience for Contemporary Art in Africa – Kerryn Greenberg In 2010, during a conference at Tate Modern on curatorial practice in Africa, Raphael Chikukwa (National Gallery of Zimbabwe) and Riason Naidoo (South African National Gallery) marvelled at the long queues they passed on their way into the Turbine Hall. While Tate Modern attracts on average five million visitors a year, for it and other major public institutions in Europe and America, diversifying and sustaining such an audience remains a priority.1 In Africa, where arts education is limited and museums, where they exist, are often seen as a product of colonialism and the domain of the elite, establishing a sizeable local audience is arguably one of the biggest challenges facing arts professionals. Since the Dakar Biennale was conceived in 1989 and first realized in 1990, efforts to build audiences for contemporary art across the continent have escalated and diversified. Some of these strategies have been more successful than others. In 1995 the inaugural Johannesburg Biennale em- phasized local artistic production in the new South Africa, but it was criticized for being too inward looking. In 1997, the second Johannesburg Biennale was internationally acclaimed and launched Okwui Enwezor’s career, but failed to gather enough local support to continue.2 Since then, numer- ous curators have explored a wide range of approaches to foster appreciation for the visual arts in their