In This Context: Collaborations & Biennials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is Modern Art 2014/15 Season Lisa Portes Lisa

SAVERIO TRUGLIA PHOTOGRAPHY BY PHOTOGRAPHY BY 2014/15 SEASON STUDY GUIDE THIS IS MODERN ART (BASED ON TRUE EVENTS) WRITTEN BY IDRIS GOODWIN AND KEVIN COVAL DIRECTED BY LISA PORTES FEBRUARY 25 – MARCH 14, 2015 INDEX: 2 WELCOME LETTER 4 PLAY SYNOPSIS 6 COVERAGE OF INCIDENT AT ART INSTITUTE: MODERN ART. MADE YOU LOOK. 7 CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS 8 PROFILE OF A GRAFFITI WRITER: MIGUEL ‘KANE ONE’ AGUILAR 12 WRITING ON THE WALL: GRAFFITI GIVES A VOICE TO THE VOICELESS with classroom activity 16 BRINGING CHICAGO’S URBAN LANDSCAPE TO THE STEPPENWOLF STAGE: A CONVERSATION WITH PLAYWRIGHT DEAR TEACHERS: IDRIS GOODWIN 18 THE EVOLUTION OF GRAFFITI IN THE UNITED STATES THANK YOU FOR JOINING STEPPENWOLF FOR YOUNG ADULTS FOR OUR SECOND 20 COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS SHOW OF 2014/15 SEASON: CREATE A MOVEMENT: THE ART OF A REVOLUTION. 21 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 22 NEXT UP: PROJECT COMPASS In This Is Modern Art, we witness a crew of graffiti writers, Please see page 20 for a detailed outline of the standards Made U Look (MUL), wrestling with the best way to make met in this guide. If you need further information about 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS people take notice of the art they are creating. They choose the way our work aligns with the standards, please let to bomb the outside of the Art Institute to show theirs is us know. a legitimate, worthy and complex art form born from a rich legacy, that their graffiti is modern art. As the character of As always, we look forward to continuing the conversations Seven tells us, ‘This is a chance to show people that there fostered on stage in your classrooms, through this guide are real artists in this city. -

Contemporary Art Biennials in Dakar and Taipei

Geogr. Helv., 76, 103–113, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-76-103-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. supported by Obscuring representation: contemporary art biennials in Dakar and Taipei Julie Ren Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Julie Ren ([email protected]) Received: 20 December 2019 – Revised: 19 February 2021 – Accepted: 22 February 2021 – Published: 7 April 2021 Abstract. There has been a proliferation of contemporary art biennials in the past 20 years, especially in cities outside of North America and Europe. What biennials represent to their host cities and what is represented at these events reveal a great deal about the significance of this proliferation. The biennial platform entails formalistic notions of representation with regards to place branding or the selection of artists as emissaries of countries where they were been born, reside, or to which they have some kind of affinity. This notion of representation is obscured considering the instability of center and periphery, artists’ biographies, practices, and references. In contradistinction to the colonial world fair, the biennial thwarts the notion or possibility of “authentic” representation. The analysis incorporates works shown at the 2018 biennials in Dakar and Taipei, interviews with artists, curators, and stakeholders, and materials collected during fieldwork in both cities. 1 Introduction Dak’Art is the largest international art festival on the conti- nent and is intended as a showcase for contemporary African In Christian Nyampeta’s video artwork “Life After Life,” he art, meaning that only artists of the continent and the African conveys a story “about a man who dies and is accidentally diaspora exhibit (Nwezi, 2013; Filitz, 2017). -

Download This PDF File

Podcasting as Activism and/or Entrepreneurship: Cooperative Networks, Publics and African Literary Production Madhu Krishnan; Kate Wallis University of Bristol; University of Exeter, UK In April 2017, we were present at a workshop titled “Personal Histories, Personal Archives, Alternative Print Cultures,” organized as part of the AHRC Research Network “Small Magazines, Literary Networks and Self-Fashioning in Africa and its Diasporas” (see Smit for a report on the session). The workshop was held at the now-defunct Long Street premises of Chimurenga, a self-described “project-based mutable object, publication, pan-African platform for editorial and curatorial work” based in Cape Town and best known for their eponymous magazine, which published sixteen issues between 2002 and 2011 (Chimurenga). As part of a conversation with collaborators Billy Kahora and Bongani Kona, editor Stacy Hardy was asked how Chimurenga sought out and forged readerships and publics. In her response, Hardy argued that the idea of a “target market” was “dangerous” and “arrogant,” offering a powerful repudiation to dominant models within the global publishing industry and book trade. Chimurenga, Hardy explained, worked from the premise articulated by founder Ntone Edjabe that “you don’t have to find readers, they find you.” Chimurenga’s ethos, Hardy explained, was one based on recognition, what she terms the “recognition of being part of something,” of “encountering Chimurenga and clocking into belonging” (Hardy, Kahora and Kona). Readers, for Hardy, were “Chimurenga people” who would find the publication and, on finding it, find something of themselves within it, be it through engagement with the magazine, attendance at Chimurenga’s live events and parties, or participation in the collective’s online presence. -

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value Doseline Wanjiru Kiguru Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Dr. Daniel Roux and Dr. Mathilda Slabbert Department of English Studies Stellenbosch University March 2016 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Signature…………….………….. Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedication To Dr. Mutuma Ruteere iii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates the centrality of international literary awards in African literary production with an emphasis on the Caine Prize for African Writing (CP) and the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (CWSSP). It acknowledges that the production of cultural value in any kind of setting is not always just a social process, but it is also always politicised and leaning towards the prevailing social power. The prize-winning short stories are highly influenced or dependent on the material conditions of the stories’ production and consumption. The content is shaped by the prize, its requirements, rules, and regulations as well as the politics associated with the specific prize. As James English (2005) asserts, “[t]here is no evading the social and political freight of a global award at a time when global markets determine more and more the fate of local symbolic economies” (298). -

Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Translation & Restitution

IN THE FOREGROUND: CONVERSATIONS ON ART & WRITING A Podcast from the Research and Academic Program (RAP) at the Clark Art Institute “A Gesture of Reciprocity”: Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Translation & Restitution Season 2, Episode 3 Recording date: OctoBer 14, 2020 Release date: FeBruary 23, 2021 Transcript Caro Fowler Welcome to In the Foreground: Conversations on Art & Writing. I am Caro Fowler, your host and director of the Research and Academic Program at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. In this series of conversations, I talk with art historians and artists about what it means to write history and make art, and the ways in which making informs how we create not only our world, But also ourselves. In this episode, I speak with Lorraine O’Grady, an artist and critic whose installations, performances, and writings address issues of hyBridity and Black female suBjectivity, particularly the role these have played in the history of modernism. Lorraine discusses her long standing research into the relation of Charles Baudelaire and Jeanne Duval, the omissions of art historical scholarship and intersectional feminism, and the entanglement of personal and social histories in her work. Souleymane Bachir Diagne The translator, when she's dealing with two languages, and trying to give clarity to a meaning from a language to another language, that is this way of putting them in touch, to create an encounter between these two languages is an ethical gesture, it is a gesture of reciprocity. Caro Fowler Thank you for joining me today, Bachir. It's really nice to talk to you. -

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing

Poetics and Politics in Contemporary African Travel Writing Maureen Amimo Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Louise Green Co-supervisor: Prof Grace Musila March 2020 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: ……………………………………… Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates contemporary travel narratives about Africa by Africans authors. Scholarship on travel writing about Africa has largely centred examples from the Global North, yet there is a rich body of travel writing by African authors. I approach African travel writing as an emerging genre that allows African authors to engage their marginality within the genre and initiate a transformative poetics inscribing alternative politics as viable forms of meaning-making. I argue that contemporary African travel writing stretches and redefines the aesthetic limits of the genre through experimentation which enables the form to carry the weight and complexities of African experiences. Drawing on the work of theorists such as Edward Said, Mary Louise Pratt, James Clifford and Syed Manzurul Islam, as well as local philosophy emergent from the texts, I examine the reimaginations of the form of the travel narrative, which centre African experiences. -

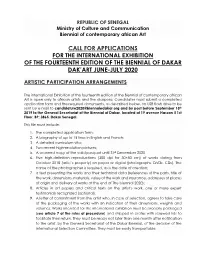

Call for Applications for the International Exhibition of the Fourteenth Edition of the Biennial of Dakar Dak’Art June-July 2020

REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL Ministry of Culture and Communication Biennial of contemporary african Art CALL FOR APPLICATIONS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF THE FOURTEENTH EDITION OF THE BIENNIAL OF DAKAR DAK’ART JUNE-JULY 2020 ARTISTIC PARTICIPATION ARRANGEMENTS The international Exhibition of the fourteenth edition of the Biennial of contemporary african Art is open only to african artists and the diaspora. Candidates must submit a completed application form and the required documents, as described below, on USB flash drive to be sent by e-mail to [email protected] and by post before September 15th 2019 to the General Secretariat of the Biennial of Dakar, located at 19 avenue Hassan II 1st Floor. BP: 3865. Dakar Senegal. This file must include: 1. The completed application form; 2. A biography of up to 15 lines in English and French; 3. A detailed curriculum vita; 4. Two recent high-resolution pictures; 5. A scanned copy of the valid passport until 31st December 2020 6. Five high-definition reproductions (300 dpi for 30×50 cm) of works dating from October 2018 (artist’s property) on paper or digital (photographs, DVDs, CDs). The name of the photographer is required, as is the date of creation; 7. a text presenting the works and their technical data (references of the parts, title of the work, dimensions, materials, value of the work and insurance, addresses of places of origin and delivery of works at the end of The biennial 2020); 8. Articles in art papers and critical texts on the artist’s work, one or more expert testimonials recognized (optional). -

DAK'art 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3

DAK’ART 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3 – June, 2 — 2016 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale « The City in the Blue Daylight » Simon Njami, Artistic Director PRESS RELEASE CONTENT 1. What Is Dak’art 2. The City In The Blue Daylight 3. Who’s Simon Njami 4. The Program of Dak’art 2016 5. Participating artists 6. Contact 1. WHAT IS DAK’ART Dak’Art, The Dakar Biennale, is the first and the major international Art event dedicated to the Contemporary African creation. Initiated in 1996 by the Republic of Senegal, the biennale is organized by the Ministry of Culture and Communication. Its 12th edition will take place from May 3, to July 11, 2016. The aims of Dak’Art are to offer the African artists a chance to show their work to a large and international audience, and to elaborate a dis- course in esthetic, by participating to the conceptualization of theorical tools for analyse and appropriation of the global art world. Mahmadou Rassoul Seydi is the General Secretary of Dak’Art. Simon Njami, writer and independant curator, is the Artistic Director of the 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale. As a departure for Dak’Art 2016, with the title « The City in the Blue Daylight », Simon Njami chose an extract from a poem written by Leopold Sedar Senghor : « Your voice tells us about the Republic that we shall erect the City in the Blue Daylight In the equality of sister nations. And we, we answer: Presents, Ô Guélowâr ! » Those verses inspire Simon Njami’s ambition for the Biennale : to make Dak’Art a « new Bandung for Culture ». -

![Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Décembre 2019, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2419/anthrovision-vol-7-1-2019-%C2%AB-aesthetic-encounters-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-30-d%C3%A9cembre-2019-consult%C3%A9-le-21-janvier-2021-1812419.webp)

Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Décembre 2019, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021

Anthrovision Vaneasa Online Journal Vol. 7.1 | 2019 Aesthetic Encounters The Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts, Design and Literature Thomas Fillitz (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/anthrovision/4332 DOI : 10.4000/anthrovision.4332 ISSN : 2198-6754 Éditeur VANEASA - Visual Anthropology Network of European Association of Social Anthropologists Référence électronique Thomas Fillitz (dir.), Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 décembre 2019, consulté le 21 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/anthrovision/4332 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/anthrovision.4332 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 janvier 2021. © Anthrovision 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction: Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts Thomas Fillitz Marketing African and Oceanic Art at the High-end of the Global Art Market: The Case of Christie’s and Sotheby’s Tamara Schild Dak’Art Off. Between Local Art Forms and Global Art Canon Discourses. Thomas Fillitz Returning to Form: Anthropology, Art and a Trans-Formal Methodological Approach Alex Flynn et Lucy Bell A Journey from Virtual and Mixed Reality to Byzantine Icons via Buddhist Philosophy Possible (Decolonizing) Dialogues in Visuality across Time and Space Paolo S. H. Favero Value, Correspondence, and Form: Recalibrating Scales for a Contemporary Anthropology of Art (Epilogue) Jonas Tinius Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019 2 Introduction: Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts Thomas Fillitz 1 Short versions of the following articles were presented at the panel ‘Aesthetic Encounters: The Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts, Design and Literature,’ which Paula Uimonen (Stockholm University) and I organized at the fifteenth biennial conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists in Stockholm 2018. -

Dak'art Biennale Has Taken Place Bi-Annually

Dak’Art Biennale – Analysis of the Critiques 1993–2016 Master’s Thesis Isalee Jallow Faculty of Arts: Area and Cultural studies Spring 2019 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian maisteri Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Alue -ja kulttuurintutkimus Tekijä – Författare – Author Isalee Jallow Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Dak’Art Biennale–Analysis of the Critique 1993–2016 Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro-gradu -tutkielma 7.5.2019 44 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro gradu -tutkielmassani analysoin Dak’Art Biennaalista kirjoitettuja arvosteluja ja kritiikkejä. Dak’Art Biennale on Senegalissa, Dakarissa järjestettävä suuri ja kansainvälinen afrikkalaisen nykytaiteen näyttely. Biennaali on vuodesta 1966 esittänyt erilaista afrikkalaista taidetta aina kirjallisuudesta visuaaliseen taiteeseen. Vuodesta 1996 Dak’Art Biennaali on keskittynyt afrikkalaisen nykytaiteen esittämiseen. 2000-luvun puolella Biennaali saavutti kansainvälisen lehdistön huomion ja on sitä myötä herättänyt paljon keskustelua taidemaailmassa. Biennaali julistaa pan-afrikkalaista ideologiaa ja pyrkii luomaan yhteisöllisyyttä ja yhteisöä kaikkein afrikkalaisten välillä asuinpaikasta riippumatta. Biennaalin tärkeä tehtävä on myös herättää keskustelua afrikkalaisuudesta, kolonialismin historian vaikutuksista, ideologioista ja nykyisen Afrikan mahdollisuuksista. Tutkimukseni keskittyy siihen, millaista -

Soly Cissé Born 1969 in Senegal Lives and Works in Dakar, Senegal

Soly Cissé Born 1969 in Senegal Lives and works in Dakar, Senegal Soly Cissé is a mixed media painter and sculptor from Dakar, and is one of Senegal’s most celebrated artists. As a child, Cissé enjoyed drawing on the radiology that his father, a radiologist, brought home. Today, he is still fascinated by transparencies, light imposed on darkness, the essence of colours. When he paints, his brush reveals a scene, brings light to a story, and frees the characters trapped in the black background. Cissé’s artworks are profoundly inspired by and contextualized through his upbringing. He grew up during an epoch of transition, following Senegal’s period of social and political unrest, where art served as mode of social activism and self-expression for the disenfranchised persons. His work, like a portal where the imagined and physical realms convene, intuitively explores notions of duality and repetition; tradition and modernity, the spiritual and the secular. Soly refuses to imitate and abhors illustration. His work gives birth to a new world, populated by creatures neither completely human, neither completely animal nor completely legendary. Cissé’s spontaneous painterly movements, textured accents and neo-expressionistic techniques form depictions reflective of the dissolution of society’s moral thresholds, shifts attributable to globalization and modernization. Shapeless human characters distort into anthropomorphic shadows of the other self; identities lost in translation from the past to the contemporary and abstract lines and bold strokes -

+| Download the Pdf Version

“Embracing Opacity” Interview with Ntone Edjabe (Chimurenga Magazine) Ntone Edjabe is the founder and editor of Chimurenga, a literary magazine produced in Cape Town focusing on contemporary African politics and popular culture. The title Chimurenga refers to the Shona word for ‘struggle’ as well as to a popular music genre in Zimbabwe. In this conversation on July 14th 2011, Edjabe looks back at the first decade of publishing Chimurenga and speaks about the philosophy underlying the publication. His current project, The Chimurenga Chronicle, takes on the form of a newspaper backdated to the week of May 11 – 18 2008, the period marked by the outbreak of so-called xenophobic violence in South Africa. In an effort to shift the perspective away from the confines of nation-states The Chimurenga Chronicle is produced in cooperation with independent publishers Kwani? in Kenya and Nigeria’s Cassava Republic Press. The newspaper will be released on October 19th 2011, the day known in South Africa as “Black Wednesday” since the historic day in 1977 when the apartheid regime declared 19 Black Consciousness organisations illegal and banned two newspapers. Subtitled “A speculative, future-forward newspaper that travels back in time to re-imagine the present”, The Chimurenga Chronicle engages with the call of theorist Achille Mbembe, to “imagine new forms of mobilization and leadership, to create an ‘intellectual plus-value’ based on a ‘concept-of-what-will-come’”. The first edition of Chimurenga was published in 2002. Approaching your 10th anniversary as a literary magazine, what are some of the changes and continuities characterising the Chimurenga publication? There was no clear strategy behind the project in the beginning, and I think that is perhaps one of the reasons why we are still here.