Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Translation & Restitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

Contemporary Art Biennials in Dakar and Taipei

Geogr. Helv., 76, 103–113, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-76-103-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. supported by Obscuring representation: contemporary art biennials in Dakar and Taipei Julie Ren Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Julie Ren ([email protected]) Received: 20 December 2019 – Revised: 19 February 2021 – Accepted: 22 February 2021 – Published: 7 April 2021 Abstract. There has been a proliferation of contemporary art biennials in the past 20 years, especially in cities outside of North America and Europe. What biennials represent to their host cities and what is represented at these events reveal a great deal about the significance of this proliferation. The biennial platform entails formalistic notions of representation with regards to place branding or the selection of artists as emissaries of countries where they were been born, reside, or to which they have some kind of affinity. This notion of representation is obscured considering the instability of center and periphery, artists’ biographies, practices, and references. In contradistinction to the colonial world fair, the biennial thwarts the notion or possibility of “authentic” representation. The analysis incorporates works shown at the 2018 biennials in Dakar and Taipei, interviews with artists, curators, and stakeholders, and materials collected during fieldwork in both cities. 1 Introduction Dak’Art is the largest international art festival on the conti- nent and is intended as a showcase for contemporary African In Christian Nyampeta’s video artwork “Life After Life,” he art, meaning that only artists of the continent and the African conveys a story “about a man who dies and is accidentally diaspora exhibit (Nwezi, 2013; Filitz, 2017). -

Culture: the Bedrock of Peace; the UNESCO Courier; Vol.:3; 2017

THE UNESCO CourierOctober-December 2017 • n°3 Culture : the bedrock of peace United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Our contributors Marc Chassaubéné Virginie Jourdan France Brandi Harless Samuel Hardy Bruce Howe United Kingdom Deeyah Khan Sarah Willcox Norway United States Diego Ibarra Sánchez Bujor Nedelcovici Spain Romania Asaad Zoghaib Lebanon Spôjmaï Zariâb Afghanistan Catherine Fiankan-Bokonga Switzerland, DRC Jiang Bo China Rithy Panh Souleymane Cambodia Bachir Diagne Senegal Edouard J. Maunick Abderrahmane Mauritius Sissako Mauritania Magdalena Nandege South Sudan Véronique Tadjo Côte d’Ivoire Marie Angélique Ingabire Rwanda Kate Panayotou Ahmad Australia Al Faqi Al Mahdi Ouided Bouchamaoui Zenaldo Coutinho Mayombo Kassongo Mounir Char Dave Cull Brazil Mali Tunisia New Zealand @ Alvaro Cabrera Jimenez / Shutterstock 2017 • n° 3 • Published since 1948 Language Editors: Information and reproduction rights: Arabic: Anissa Barrak [email protected] The UNESCO Courier is published quarterly Chinese: China Translation and Publishing House 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France by the United Nations Educational, Scientific English: Shiraz Sidhva © UNESCO 2017 and Cultural Organization. It promotes the French: Isabelle Motchane-Brun ISSN 2220-2285 • e-ISSN 2220-2293 ideals of UNESCO by sharing ideas on issues of Russian: Marina Yaloyan international concern relevant to its mandate. Spanish: Lucía Iglesias Kuntz Periodical available in Open Access under the The UNESCO Courier is published thanks to the Translation (English): Peter Coles, Cathy Nolan Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) licence generous support of the People’s Republic of China. Design: Corinne Hayworth (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ igo/). Director of Publication: Éric Falt Cover image : © Selçuk By using the content of this publication, the users accept Printing: UNESCO to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Executive Director: Vincent Defourny Access Repository (www.unesco. -

Downloaded From: Version: Accepted Version Publisher: American Academy of Religion (AAM)

Strickland, Lloyd (2019)Book Review: Open to Reason: Muslim Philosophers in Conversation with the Western Tradition. American Academy of Religion (AAM). Downloaded from: http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/622602/ Version: Accepted Version Publisher: American Academy of Religion (AAM) Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Open to Reason: Muslim Philosophers in Conversation with the Western Tradition Souleymane Bachir Diagne New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. 120 pages. Hardback. ISBN 978-0231185462. Open to Reason: Muslim Philosophers in Conversation with the Western Tradition is an English translation of Souleymane Bachir Diagne’s short but exceedingly rich Comment philosopher en Islam?, first published in 2008. Diagne’s aim is to draw attention to the philosophical spirit that has been present in Islam from its inception and, to this end, he offers a potted history of Islamic philosophy, or at least of some of Islam’s interactions with Western philosophy. The book consists of ten chapters, each of which focuses on philosophers from either the classical period (9th – 12th centuries) or the modern (19th – 20th centuries), and a brief conclusion. Chapter 1 (“And how to not philosophize?”) offers a brief history of the Qur’an and an account of how Islamic philosophizing arose as a result of the disputes between the Shi’a and Sunni communities over who should be considered the prophet Muhammad’s rightful successor as “commander of the faithful” (3). Both sides believed the answer could be reached through fidelity to Muhammad and to his message in the Qur’an, but as Diagne notes, “when the meaning of fidelity itself proves to be a matter of speculation, how not to philosophize?” (4). -

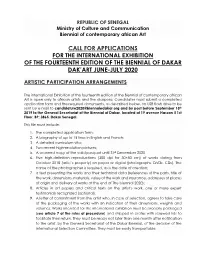

Call for Applications for the International Exhibition of the Fourteenth Edition of the Biennial of Dakar Dak’Art June-July 2020

REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL Ministry of Culture and Communication Biennial of contemporary african Art CALL FOR APPLICATIONS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF THE FOURTEENTH EDITION OF THE BIENNIAL OF DAKAR DAK’ART JUNE-JULY 2020 ARTISTIC PARTICIPATION ARRANGEMENTS The international Exhibition of the fourteenth edition of the Biennial of contemporary african Art is open only to african artists and the diaspora. Candidates must submit a completed application form and the required documents, as described below, on USB flash drive to be sent by e-mail to [email protected] and by post before September 15th 2019 to the General Secretariat of the Biennial of Dakar, located at 19 avenue Hassan II 1st Floor. BP: 3865. Dakar Senegal. This file must include: 1. The completed application form; 2. A biography of up to 15 lines in English and French; 3. A detailed curriculum vita; 4. Two recent high-resolution pictures; 5. A scanned copy of the valid passport until 31st December 2020 6. Five high-definition reproductions (300 dpi for 30×50 cm) of works dating from October 2018 (artist’s property) on paper or digital (photographs, DVDs, CDs). The name of the photographer is required, as is the date of creation; 7. a text presenting the works and their technical data (references of the parts, title of the work, dimensions, materials, value of the work and insurance, addresses of places of origin and delivery of works at the end of The biennial 2020); 8. Articles in art papers and critical texts on the artist’s work, one or more expert testimonials recognized (optional). -

DAK'art 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3

DAK’ART 2016 BIENNALE of DAKAR May, 3 – June, 2 — 2016 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale « The City in the Blue Daylight » Simon Njami, Artistic Director PRESS RELEASE CONTENT 1. What Is Dak’art 2. The City In The Blue Daylight 3. Who’s Simon Njami 4. The Program of Dak’art 2016 5. Participating artists 6. Contact 1. WHAT IS DAK’ART Dak’Art, The Dakar Biennale, is the first and the major international Art event dedicated to the Contemporary African creation. Initiated in 1996 by the Republic of Senegal, the biennale is organized by the Ministry of Culture and Communication. Its 12th edition will take place from May 3, to July 11, 2016. The aims of Dak’Art are to offer the African artists a chance to show their work to a large and international audience, and to elaborate a dis- course in esthetic, by participating to the conceptualization of theorical tools for analyse and appropriation of the global art world. Mahmadou Rassoul Seydi is the General Secretary of Dak’Art. Simon Njami, writer and independant curator, is the Artistic Director of the 12th Edition of the Dakar Biennale. As a departure for Dak’Art 2016, with the title « The City in the Blue Daylight », Simon Njami chose an extract from a poem written by Leopold Sedar Senghor : « Your voice tells us about the Republic that we shall erect the City in the Blue Daylight In the equality of sister nations. And we, we answer: Presents, Ô Guélowâr ! » Those verses inspire Simon Njami’s ambition for the Biennale : to make Dak’Art a « new Bandung for Culture ». -

The Gift Hau Books

THE GIFT Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com THE GIFT EXPANDED EditION Marcel Mauss Selected, Annotated, and Translated by Jane I. Guyer Foreword by Bill Maurer Hau Books Chicago © 2016 Hau Books and Jane I. Guyer © 1925 Marcel Mauss, L’Année Sociologique, 1923/24 (Parts I, II, and III) Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Cover Photograph Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, PM# 2004.29.3440 (digital file# 174010013) Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-0-6 LCCN: 2015952084 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents foreword “Puzzles and Pathways” by Bill Maurer ix translator’s introduction “The Gift that Keeps on Giving” by Jane I. Guyer 1 PART I: IN MEMORIAM In Memoriam: The Unpublished Work of Durkheim and His Collaborators 29 I.) Émile Durkheim 31 a. Scientific Courses 33 b. Course on the History of Doctrines 37 c. Course in Pedagogy 39 II.) The Collaborators 42 PART II: ESSAY ON THE GIFT: THE FORM AND SENSE OF EXCHANGE IN ARCHAIC SOCIETIES vi THE GIFT Introduction Of the Gift and in Particular of the Obligation to Return Presents -

![Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Décembre 2019, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2419/anthrovision-vol-7-1-2019-%C2%AB-aesthetic-encounters-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-30-d%C3%A9cembre-2019-consult%C3%A9-le-21-janvier-2021-1812419.webp)

Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 30 Décembre 2019, Consulté Le 21 Janvier 2021

Anthrovision Vaneasa Online Journal Vol. 7.1 | 2019 Aesthetic Encounters The Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts, Design and Literature Thomas Fillitz (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/anthrovision/4332 DOI : 10.4000/anthrovision.4332 ISSN : 2198-6754 Éditeur VANEASA - Visual Anthropology Network of European Association of Social Anthropologists Référence électronique Thomas Fillitz (dir.), Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019, « Aesthetic Encounters » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 décembre 2019, consulté le 21 janvier 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/anthrovision/4332 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/anthrovision.4332 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 janvier 2021. © Anthrovision 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction: Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts Thomas Fillitz Marketing African and Oceanic Art at the High-end of the Global Art Market: The Case of Christie’s and Sotheby’s Tamara Schild Dak’Art Off. Between Local Art Forms and Global Art Canon Discourses. Thomas Fillitz Returning to Form: Anthropology, Art and a Trans-Formal Methodological Approach Alex Flynn et Lucy Bell A Journey from Virtual and Mixed Reality to Byzantine Icons via Buddhist Philosophy Possible (Decolonizing) Dialogues in Visuality across Time and Space Paolo S. H. Favero Value, Correspondence, and Form: Recalibrating Scales for a Contemporary Anthropology of Art (Epilogue) Jonas Tinius Anthrovision, Vol. 7.1 | 2019 2 Introduction: Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts Thomas Fillitz 1 Short versions of the following articles were presented at the panel ‘Aesthetic Encounters: The Politics of Moving and (Un)settling Visual Arts, Design and Literature,’ which Paula Uimonen (Stockholm University) and I organized at the fifteenth biennial conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists in Stockholm 2018. -

Dak'art Biennale Has Taken Place Bi-Annually

Dak’Art Biennale – Analysis of the Critiques 1993–2016 Master’s Thesis Isalee Jallow Faculty of Arts: Area and Cultural studies Spring 2019 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian maisteri Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Alue -ja kulttuurintutkimus Tekijä – Författare – Author Isalee Jallow Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Dak’Art Biennale–Analysis of the Critique 1993–2016 Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro-gradu -tutkielma 7.5.2019 44 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro gradu -tutkielmassani analysoin Dak’Art Biennaalista kirjoitettuja arvosteluja ja kritiikkejä. Dak’Art Biennale on Senegalissa, Dakarissa järjestettävä suuri ja kansainvälinen afrikkalaisen nykytaiteen näyttely. Biennaali on vuodesta 1966 esittänyt erilaista afrikkalaista taidetta aina kirjallisuudesta visuaaliseen taiteeseen. Vuodesta 1996 Dak’Art Biennaali on keskittynyt afrikkalaisen nykytaiteen esittämiseen. 2000-luvun puolella Biennaali saavutti kansainvälisen lehdistön huomion ja on sitä myötä herättänyt paljon keskustelua taidemaailmassa. Biennaali julistaa pan-afrikkalaista ideologiaa ja pyrkii luomaan yhteisöllisyyttä ja yhteisöä kaikkein afrikkalaisten välillä asuinpaikasta riippumatta. Biennaalin tärkeä tehtävä on myös herättää keskustelua afrikkalaisuudesta, kolonialismin historian vaikutuksista, ideologioista ja nykyisen Afrikan mahdollisuuksista. Tutkimukseni keskittyy siihen, millaista -

Soly Cissé Born 1969 in Senegal Lives and Works in Dakar, Senegal

Soly Cissé Born 1969 in Senegal Lives and works in Dakar, Senegal Soly Cissé is a mixed media painter and sculptor from Dakar, and is one of Senegal’s most celebrated artists. As a child, Cissé enjoyed drawing on the radiology that his father, a radiologist, brought home. Today, he is still fascinated by transparencies, light imposed on darkness, the essence of colours. When he paints, his brush reveals a scene, brings light to a story, and frees the characters trapped in the black background. Cissé’s artworks are profoundly inspired by and contextualized through his upbringing. He grew up during an epoch of transition, following Senegal’s period of social and political unrest, where art served as mode of social activism and self-expression for the disenfranchised persons. His work, like a portal where the imagined and physical realms convene, intuitively explores notions of duality and repetition; tradition and modernity, the spiritual and the secular. Soly refuses to imitate and abhors illustration. His work gives birth to a new world, populated by creatures neither completely human, neither completely animal nor completely legendary. Cissé’s spontaneous painterly movements, textured accents and neo-expressionistic techniques form depictions reflective of the dissolution of society’s moral thresholds, shifts attributable to globalization and modernization. Shapeless human characters distort into anthropomorphic shadows of the other self; identities lost in translation from the past to the contemporary and abstract lines and bold strokes -

The Biennial of Dakar and South-South Circulations

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 5 Article 6 Issue 2 South - South Axes of Global Art 2016 The ieB nnial of Dakar and South-South Circulations Thomas Fillitz University of Vienna, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Fillitz, Thomas. "The ieB nnial of Dakar and South-South Circulations." Artl@s Bulletin 5, no. 2 (2016): Article 6. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. South-South The Biennial of Dakar and South-South Circulations Thomas Fillitz * University of Vienna Abstract The Biennale of Dakar is considered as a particular site for examining South-South circulations of artworks. Being the biennial of contemporary African art, only artists from Africa and its Diaspora are eligible for its central, international exhibition. Several factors, however, are strongly influencing these selections, among others the Biennale’s specific selection procedures, as for instance the appointment of the members of the selection committee. Considering critical voices of local artists about the Biennale’s performance will lead to discussing several problems that affect South-South circulations of artworks. -

The Arts and Globalization - Alioune Sow

LITERATURE AND THE FINE ARTS – The Arts and Globalization - Alioune Sow THE ARTS AND GLOBALIZATION Alioune Sow Faculty of Arts, Letters and Social Sciences, University of Yaounde1, Yaounde Cameroon Keywords: Globalization, linear, continuous, uniform progress, world literature, diversity of local forms of life, intersubjectivity of understanding, intercultural, imagined communities, ambivalence, critical theory of modernization, rehabilitation of the local Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reevaluation of Values and Reinvention of Identity 3. “World Literature’’ And Globalization 4. Global and Local: A Typology of Arts 5. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The globalization phenomenon acts in the world like a storm that sweeps all in its way. This phenomenon tries to put together many differents cultures. But every culture develops a resistance against a level of globalization. Nevertheless, each culture must be open to reevaluations and should be in search of new equilibrium. Following the Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne, the paper develops the idea that, evaluation comes before values and it is the raison d’être of these values. This implies that it is necessary for a culture to be its own historian. So, it is necessary to invent a different discourse in the face of the globalization phenomenon. In effect, the author thinks that the notion of world literature is appropriated to bring out a discussion on the Arts and the Globalization. Literature is a medium for presenting human forms of conscience and social phenomena. It also helps in evaluating human costs resultingUNESCO from social rise in efficiency – followingEOLSS the current globalization thrust and also in identifying its victims. Literature traces the possibility of the diversity of ways towards theSAMPLE better living conditions of communitiesCHAPTERS that are able to conceive an ‘’incubation’’ program for modern science and its props.