The Public Service Broadcaster of Lithuania in the Era of Commercialization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automatinę Kanalų Paiešką“

Dėl techninių aplinkybių keisis skaitmeninės Teo televizijos kanalų tinklelis. Pokyčiai vyks dviem etapais – 2016 m. gegužės 1 d. ir 2016 m. liepos 1 d. Pokyčiai didesnės TV signalo aprėpties zonoje Pokyčiai mažesnės TV signalo aprėpties zonoje (iki 40-ies TV kanalų) (iki 30-ies TV kanalų) Nauji kanalai nuo 2016 05 01 Naujas kanalas nuo 2016 05 01 Viasat Nature, Setanta Sports, TNT. Viasat Nature, TNT. Išjungiami kanalai nuo 2016 05 01: CNN, Discovery Science, Išjungiami kanalai nuo 2016 05 01: Animal Planet, Animal Planet, Discovery World, Eurosport2, TLC. Sony Turbo, Sony Channel, TLC. Išjungiami kanalai nuo 2016 07 01: RTL. Išjungiami kanalai nuo 2016 07 01: Cartoon Network, Dožd, BBC World News, VH1, RTL. Galutinis kanalų sąrašas po pakeitimų Galutinis kanalų sąrašas po pakeitimų LRT Televizija Viasat Nature LRT Televizija Eurosport LRT Kultūra Sony Turbo LRT Kultūra Sport1 TV3 Sony Channel TV3 KidZone TV TV8 FOX TV8 Playboy TV TV6 FOX Life TV6 Travel Channel LNK Balticum Auksinis LNK TNT Info TV Eurosport Info TV Liuks! Sport1 Liuks! TV1 Setanta Sports TV1 BTV Nickelodeon BTV Lietuvos rytas TV KidZone TV Lietuvos rytas TV BBC World News Cartoon Network Pervyj Baltiskij Kanal Euronews Playboy TV TVCi Pervyj Baltiskij Kanal Travel Channel Discovery Channel TVCi MTV National Geographic Channel Dožd TVP Polonia Viasat Nature Discovery Channel VH1 Europe Balticum Auksinis National Geographic Channel TNT FOX Nauji kanalai Viasat Nature – aukštos kokybės geriausios Setanta Sports – kanalas siūlo daugiau nei 80 TNT - tai pramoginis TV kanalas, garsėjantis dokumentinės laidos ir filmai apie gamtą ir futbolo, ledo ritulio, teniso, golfo ir kitų sporto pripažintais humoro projektais (kaip „Comedy gyvūnų pasaulį visuose egzotiškuose Žemės šakų tiesioginių transliacijų per mėnesį (ka- Club“), laidomis ir TV serialais su garsiais rusų kampeliuose. -

Is There Life After the Crisis?

is There Life afTer The crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe is There Life afTer The crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe Sources of information: Lursoft – database on companies Lithuanian Company Register ORBIS – database of companies, ownership and financial data worldwide. Data harvesters: Rudīte Spakovska, Aija Krūtaine, Mikk Salu, Mantas Dubauskas Authors: Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe Special thanks to Anders Alexanderson, Uldis Brūns, Ārons Eglītis For re-publishing written permission shall be obtained prior to publishing. © The Centre for Media Studies at SSE Riga © The Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism Re:Baltica Riga, 2014 Is There Life After The Crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Contents How Baltic Media Experts View the Sector ...............................................................................................................4 Introduction: Media After Crisis ..................................................................................................................................7 Main Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................................8 Changes In Turnover of Leading Baltic Media, 2013 vs 2008 ................................................................................9 -

DICE Best Practice Guide.Pdf

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE Interactive Service, Frequency Social Business Migration, Policy & Platforms Acceptance Models Implementation Regulation & Business Opportunities BEST PRACTICE GUIDE FOREWORD As Lead Partner of DICE I am happy to present this We all want to reap the economic benefi ts of dig- best practice guide. Its contents are based on the ital convergence. The development and successful outputs of fi ve workgroups and countless discus- implementation of new services need extended sions in the course of the project and in conferences markets, however; markets which often have to be and workshops with the broad participation of in- larger than those of the individual member states. dustry representatives, broadcasters and political The sooner Europe moves towards digital switcho- institutions. ver the sooner the advantages of released spectrum can be realised. The DICE Project – Digital Innovation through Co- operation in Europe – is an interregional network We have to recognise that a pan-European telecom funded by the European Commission. INTERREG as and media industry is emerging. The search for an EU community initiative helps Europe’s regions economies of scale is driving the industry into busi- form partnerships to work together on common nesses outside their home country and to strategies projects. By sharing knowledge and experience, beyond their national market. these partnerships enable the regions involved to develop new solutions to economic, social and envi- It is therefore a pure necessity that regional political ronmental challenges. institutions look across the border and aim to learn from each other and develop a common under- DICE focuses on facilitating the exchange of experi- standing. -

Atlyginimas Už Retransliavimą Kabelinių 4 Operatorių Tinklus Yra Didžiausias Per Visus AVAKA 2 Veiklos Metus

2017 METŲ APŽVALGA IR SKAIČIAI Audiovizualinių kūrinių retransliavimas KABELINIŲ OPERATORIŲ TINKLAIS 1. ATLYGINIMO PASKIRSTYMO PRINCIPAI Džiugina ir tai, jog AVAKA surenka vis didesnį atlyginimą Audiovizualinių kūrinių Retransliavimo kabelinių atstovaujamiems teisių turėtojams. Lyginant 2016 m. ir operatorių tinklais paskirstymas teisių turėtojams yra 2017 m., surinkimas augo daugiau negu 3 %. atliekamas vadovaujantis LR Autorių teisių ir gretutinių teisių įstatymo nuostatomis ir AVAKA Atlyginimo, surinkto audiovizualinių kūrinių autoriams ir gamintojams (prodiuseriams) už audiovizualinių kūrinių retransliavimą, paskirstymo taisyklių (toliau – Paskirstymo taisyklės) nuostatomis. Atlyginimas teisių turėtojams, išskyrus atlyginimą muzikinių klipų teisių turėtojams (žiūrėti 3 punktą), apskaičiuojamas remiantis: 2017 m. 2016 m. AUDIOVIZUALIO RETRANSLIUOJAMŲ KŪRINIO TRUKMĘ KANALŲ ŽIŪRIMUMĄ pav. Surinkto atlyginimo pokytis 2016-2017 m. b. PASKIRSTYTO, BET NEIŠMOKĖTO ATLYGINIMO UŽ AUDIOVIZUALINIO ANKSTESNIUS LAIKOTARPIUS. Pagal AVAKA KŪRINIO AUDIOVIZUALINIO Paskirstymo taisykles neišmokėtas atlyginimas teisių RETRANSLIAVIMO KŪRINIO ŽANRĄ turėtojams yra saugomas 3 metus. AVAKA imasi visų LAIKĄ būtinų priemonių identifikuojant audiovizualinių kūrinių teisių turėtoją, nustatant jo tapatybę. Pasibaigus 3 metų laikotarpiui, neišmokėtos sumos pridedamos 2. SKIRSTOMAS ATLYGINIMAS prie einamųjų metų paskirstymo sumos ir yra perskirstomos. AVAKA atstovaujamiems Lietuvos teisių turėtojams paskirstytas retransliavimo atlyginimas už 2017 m., Atsižvelgiant -

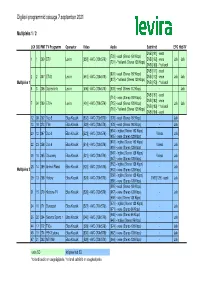

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

2020 Annual Report

Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania RADIO AND TELEVISION COMMISSION OF LITHUANIA 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 17 March 2021 No ND-1 Vilnius 1 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE ................................................................................................................ 3 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 MEMBERSHIP AND ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................................... 5 LICENSING OF BROADCASTING ACTIVITIES AND RE-BROADCAST CONTENT AND REGULATION OF UNLICENSED ACTIVITIES ............................................................................ 6 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS AND ENFORCEMENT .............................................................. 30 ECONOMIC OPERATOR OVERSIGHT AND CONTENT MONITORING ................................ 33 COPYRIGHT PROTECTION ON THE INTERNET ...................................................................... 41 STAFF PARTICIPATION IN TRAINING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION EFFORTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 42 COMPETITION OF THE BEST IN RADIO AND TELEVISION PRAGIEDRULIAI ................... 43 PUBLICITY WORK BY THE RTCL .............................................................................................. 46 PRIORITIES FOR 2021 ................................................................................................................... -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v. -

Russian Language Media in Estonia 1990–2012

This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Author(s): Jõesaar, Andres; Rannu, Salme; Jufereva, Maria Title: Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012 Year: 2013 Version: Published version Copyright: © Vytauto Didziojo universitetas, 2013 Rights: In Copyright Rights url: http://rightsstatements.org/page/InC/1.0/?language=en Please cite the original version: Jõesaar, A., Rannu, S., & Jufereva, M. (2013). Media for the minorities : Russian language media in Estonia 1990-2012. Media transformations, 9(9), 118-154. https://doi.org/10.7220/2029- 865X.09.07 ISSN 2029-865X 118 doi://10.7220/2029-865X.09.07 MEDIA FOR THE MINORITIES: RUSSIAN LANGUAGE MEDIA IN ESTONIA 1990–2012 Andres JÕESAAR [email protected] PhD, Associate Professor Baltic Film and Media School Tallinn University Head of Media Research Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Salme RANNU [email protected] Analyst Estonian Public Broadcasting Tallinn, Estonia Maria JUFEREVA [email protected] PhD Candidate University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä, Finlanda ABSTRACT: This article aims to explore the ways in which Estonian public broa- dcasting tackles one specific media service sphere; how television programmes for language minorities are created in a small country, how economics and European Union media policy have influenced this processes. The article highlights major ten- sions, namely between Estonian and Russian media outlets, Estonian and Russian speakers within Estonia and the EU and Estonia concerning the role of public ser- vice broadcasting (PSB). For research McQuail’s (2010) theoretical framework of media institutions’ influencers – politics, technology and economics – is used. -

Digital Switchover in Central and Eastern Europe

DIGITAL SWITCHOVER IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: PREMATURE OR KAROL BADLY NEEDED? JAKUBOWICZ 38 - Abstract Preparation for the digital switchover in Central and Karol Jakubowicz was Eastern Europe adds to the complexity of post-Communist (2005-2006) Chairman of the transformation in broadcasting. The following problems are Steering Committee on the apparent: (1) lack of suffi cient understanding of the issues Mass Media and New Com- involved in the digital switch-over, especially as regards the munication Services, Council broadcasting, programming and market issues involved; of Europe; (2) turf wars between broadcasting and telecommuni- e-mail: [email protected]. cations regulatory authorities; (3) the impact of politics on the process of preparation and execution of digital switchover strategies; and (4) in some cases, launching the process prematurely, for inappropriate reasons. Depending Vol.14 (2007), No. 1, pp. 21 1, pp. (2007), No. Vol.14 on one’s point of view, this is either a “premature” digital switchover in countries not yet ready for it, or a case of countries needing a wake-up call to face technological and market realities that they are not responding properly to. Poland is in the process of changing its switchover strat- egy. The process is to start in 2010 with the roll-out of one digital multiplex, covering the whole country, and carrying the existing analogue terrestrial television channels. Plans for further moves are hazy. Meanwhile, many market play- ers are launching alternative projects to take advantage of digital technology, e.g. by means of satellite technology. 21 Preparing for the Digital Switchover in the Context of Post-Communist Transformation In the media fi eld, as elsewhere, post-Communist transformation has meant that Central and Eastern European countries are faced with a major policy over- load. -

Vartotojų Informavimo Planas 2021 M

VARTOTOJŲ INFORMAVIMO APIE ELEKTROS ENERGIJOS RINKOS LIBERALIZAVIMĄ IR JO PROCESĄ PLANAS 2021 m. NUMATOMI KONKURENCINGOS ELEKTROS ENERGIJOS RINKOS SUKŪRIMO ETAPAI 2020-2023 m. Apie 793 tūkst.* II ETAPAS vartotojų ESO pateikia antro etapo Iki šios datos buitinių klientų elektros tiekėją duomenis (kurie pasirenka namų Visuomenės neišreiškė ūkiai, suvartojantys informavimo nesutikimo) >1000 kWh/metus kampanija elektros tiekėjams III ETAPAS 2021.04.05 2021.09.01 2022.12.10 2020.05-12 2021.07 2021.12.10 2023.01.01 II ETAPAS III ETAPAS Iki šios datos Visuomeninis tiekėjas Iki šios datos Įvykdytas 1-asis elektros tiekėją informuoja į pirmąjį elektros tiekėją liberalizavimo pasirenka namų etapą pateksiančius pasirenka visi etapas. ūkiai, suvartojantys buitinius klientus (747 likę namų ūkiai PASIRINKO 97% 1000>5000 tūkst.) apie elektros kWh/metus energijos tiekimo Apie 747 tūkst.* visuomenine kaina vartotojų nutraukimą. PALANKUMO VERTINIMAS Kodėl galimybę pasirinkti elektros energijos tiekėją iš keleto tiekėjų vertinate palankiai? Šaltinis: Visuomenės nuomonės tyrimas dėl elektros energijos rinkos liberalizavimo, 2020 12, UAB „Norstat“ Tyrimo duomenimis apie 98 proc. Lietuvos gyventojų girdėjo apie tai, kad gali rinktis elektros tiekėją savo namams; Tyrimo duomenimis 74 proc. apklaustųjų žino arba girdėjo apie informacinę svetainę Pasirinkitetiekeja.lt; 53% teigia trūkstantys daugiau informacijos apie tiekėjo pasirinkimo procesą. KOMUNIKACIJOS KELIAS ŽINOMUMAS SUSIDOMĖJIMAS VEIKSMAS AIŠKIOS NAUDOS: LAISVĖ RINKTIS, AIŠKUMAS: INFORMAVIMAS / EDUKAVIMAS naudų ir patarimų komunikavimas. asmens duomenų sauga, Visuomenėje suformuoti vykstančio Gerosios patirtys. Daugiau pasirinkimo proceso pokyčio žinomumą. Informuoti klientus ir akcentų: kas, kada ir kaip keisis. komunikavimas, skatinimas suteikti kuo daugiau informacijos apie nelikti garantiniame tiekime. pokytį, jo tikslus, naudą, eigą. Aiški ir paprasta, asmeniškai į žmogų nukreipta komunikacija. -

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia Contemporary media research highlights the importance of empirically analysing the relationships between media and age; changing user patterns over the life course; and generational experiences within media discourse beyond the widely-hyped buzz terms such as the ‘digital natives’, ‘Google generation’, etc. The Generational Use doctoral thesis seeks to define the ‘repertoires’ of news media that different generations use to obtain topical information and create of News Media their ‘media space’. The thesis contributes to the development of in Estonia a framework within which to analyse generational features in news audiences by putting the main focus on the cultural view of generations. This perspective was first introduced by Karl Mannheim in 1928. Departing from his legacy, generations can be better conceived of as social formations that are built on self- identification, rather than equally distributed cohorts. With the purpose of discussing the emergence of various ‘audiencing’ patterns from the perspectives of age, life course and generational identity, the thesis centres on Estonia – a post-Soviet Baltic state – as an empirical example of a transforming society with a dynamic media landscape that is witnessing the expanding impact of new media and a shift to digitisation, which should have consequences for the process of ‘generationing’. The thesis is based on data from nationally representative cross- section surveys on media use and media attitudes (conducted 2002–2012). In addition to that focus group discussions are used to map similarities and differences between five generation cohorts born 1932–1997 with regard to the access and use of established news media, thematic preferences and spatial orientations of Signe Opermann Signe Opermann media use, and a discursive approach to news formats. -

Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Department of Social Research University of Helsinki Finland NORMATIVE STORIES OF THE FORMATIVE MOMENT CONSTRUCTION OF ESTONIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY IN POSTIMEES DURING THE EU ACCESSION PROCESS Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 10, University main building, on 12 February 2016, at 12 noon. Helsinki 2016 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 1 (2016) Media and Communication Studies © Sigrid Kaasik-Krogerus Cover: Riikka Hyypiä & Hanna Sario Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN 2343-273X (Print) ISSN 2343-2748 (Online) ISBN 978-951-51-1047-3 (Paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1048-0 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2016 ABSTRACT This longitudinal research analyzes the construction of Estonian national identity in the country’s largest and oldest daily newspaper Postimees in relation to the European Union (EU) in the course of Estonia’s EU accession process 1997-2003. I combine media studies with political science, EU studies and nationalism studies to scrutinize this period as an example of a ‘formative moment’. During this formative moment the EU became ‘the new official Other’ in relation to which a new temporary community, Estonia as a candidate country, was ‘imagined’ in the paper. The study is based on the assumption that national identity as a normative process of making a distinction between us and Others occurs in societal texts, such as the media.