20000072582.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

669419-1 EFFICIENCY of AIRLINES in INDIA ABSTRACT This Paper Measures the Technical Efficiency of Various Airlines Operating In

Natarajan and Jain Efficiency of Airlines in India EFFICIENCY OF AIRLINES IN INDIA Ramachandran Natarajan, College of Business, Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville TN, 38505, U.S.A. E-Mail: [email protected] , Tel: 931-372-3001 and Ravi Kumar Jain, Icfai Business School, IFHE University, Hyderabad-501203 (AP) India. E-Mail: [email protected] , Mobile: 91+94405-71846 ABSTRACT This paper measures the technical efficiency of various airlines operating in India over a ten-year period, 2001-2010. For this, the Input Efficiency Profiling model of DEA along with the standard Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is used to gain additional insights. The study period is divided into two sub-periods, 2001-2005 and 2006-2010, to assess if there is any impact on the efficiency of airlines due to the significant entry of private operators. The study includes all airlines, private and publicly owned, both budget and full service, operating in the country offering scheduled services on domestic and international routes. While several studies on efficiency of airlines have been conducted globally, a research gap exists as to similar studies concerning airlines in India. This paper addresses that gap and thus contributes to the literature. Key Words: Airlines in India, DEA analysis, Input efficiency profiling, Productivity analysis, Technical efficiency. Introduction The civil aviation industry in India has come a long way since the Air Corporation Act was repealed in the year 1994 allowing private players to operate in scheduled services category. Several private players showed interest and were granted the status of scheduled carriers in the year 1995. However, many of those private airlines soon shut down. -

SP's Airbuz 4 of 2010

SP’s RS: 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India www.spsairbuz.net Issue: 4/2010 CORPORATE SPONSOR OF ATM-AIRPORTS-AIRLINES: INDIA INITIATIVE FOR INFRASTRUCTURE AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT Deliberations INTERVIEW: S.R. RAGHAVENDRA RAO OF AAI AIR SPACE MANAGEMENT AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION PLUS IGRUA: THE BEST FLYING TRAINING INSTITUTE INTERVIEW: TONY FERNANDES OF AIRASIA RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24198 Innovative networked solutions are key to solving today’s – and tomorrow’s – challenges. As a trusted partner and integrator of complex technologies, ITT has the expertise to create sophisticated systems that work together seamlessly. From air traffic management and electronic warfare to tactical communications and night vision systems, ITT offers an array of capabilities to answer every need. All this adds up to one result – your mission’s success. For more information, visit ittdefenceindia.com. Air traffic management solutions for India. E L E C T R O N I C S Y S T E M S • G E O S P A T I A L S Y S T E M S • I N F O R M A T I O N S Y S T E M S ITT, the Engineered Blocks logo, and ENGINEERED FOR LIFE are registered trademarks of ITT Manufacturing Enterprises, Inc., and are used under license. ©2010, ITT Corporation. Table of Contents SP’s RS: 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India www.spsairbuz.net Issue: 4/2010 Cover: CORPORATE SPONSOR OF ATM-AIRPORTS-AIRLINES: INDIA INITIATIVE FOR INFRASTRUCTURE With air travel having become less expensive, the problem of AIR air space management has TRAFFIC Lead Story MANAGEMENT acquired greater importance Deliberations INTERVIEW: S.R. -

Weekly Current Affairs May 9 - May 15 Sources- the Hindu / Indian Express / Pib / World Wide Web

WEEKLY CURRENT AFFAIRS MAY 9 - MAY 15 SOURCES- THE HINDU / INDIAN EXPRESS / PIB / WORLD WIDE WEB MAY 9th ● At the invitation of the President of the European Council Mr. Charles Michel, Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi participated in the India-EU Leaders’ Meeting. ● The meeting was held in a hybrid format with the participation of leaders of all the 27 EU Member States as well as the President of the European Council and the European Commission. ● The talks for Bilateral Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA), which began in 2007, have been deadlocked since 2013 over issues including tariffs, market access and data security status etc. ● This is the first time that the EU hosted a meeting with India in the EU+27 format. The EU+27 have met in this format only once before, with the US President in March this year. ● It is a significant political milestone and will further build on the momentum witnessed in the relationship since the 15th India-EU Summit in July 2020. The meeting was the initiative of the Portuguese Presidency of the Council of the European Union. ● ● During the meeting, the leaders exchanged views on three key thematic areas: i) foreign policy and security; ii) COVID-19, climate and environment; and iii) trade, connectivity and technology. ● The EU demanded that there are significant duty cuts in automobiles, tax reduction on wines, spirits etc, a strong intellectual property regime, relaxation in India's data localisation norms, protection to all its items with Geographical Indication etc. ● Indian demanded that Data secure status (important for India's IT sector); Ease norms on temporary movement of skilled workers, relaxation of Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) norms etc. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Competition Issues in the Air Transport Sector in India

2009 StudyStudy on on ImpactCompetition of Trade Issues in Liberalisationthe Domestic in the Information Technology SectorSegment on Development of the Air Draft ReportTransport Sector in Administrative Staff College of India HyderabadIndia Revised Final Report 2007 Administrative Staff College of India, Hyderabad Competition Issues in the Air Transport Sector in India Table of Contents Sl.No Chapter Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. ToR I 4 3. ToR II & III 15 4. ToR IV 29 5. ToR V 30 6. ToR VI & VII 43 7. ToR VIII 91 8. ToR IX 99 9. ToR X 120 10. ToR XI 121 11. Conclusions and Recommendations 126 12. References 129 ____________________________________________________asci research and consultancy ii Competition Issues in the Air Transport Sector in India List of Tables Table Title Page No. No. I.1 Calculation of HHI 12 I.2 Fleet Size of All Scheduled Airlines 12 I.3 Order for Airplanes 13 I.4 Net Profit/Loss incurred by Different Airlines 16 II.1 City Pair-wise Herfindahl index of Pax. Carried in 2006-07 28 17 II.2 Passenger Load Factor for Indian 22 II.3 Passenger Load Factor for Indian 25 II.4 Slots on Delhi-Mumbai Route 28 II.5 Average Age of Fleet 28 II.6 Fleet Size of All Scheduled Airlines 29 IV.1 Descriptive Statistics for Price Data: Delhi – Mumbai 30 IV.2 Taxes and Surcharges on Route : Delhi – Mumbai 32 IV.3 Taxes and Surcharges on Route : Mumbai – Delhi 32 IV.4 Pre merger (2006/07)-Delhi-Mumbai (passenger wise) 36 IV.5 Post Merger(2008) -Delhi Mumbai (slot wise) 36 IV.6 Pre merger (2006/07)-Delhi-Chennai (passenger wise) 37 IV.7 Post Merger(2008) -Delhi Chennai(slot wise) 37 IV.8 Pre merger (2006/07)-Bangalore-Chennai (passenger wise) 37 IV.9 Post Merger(2008) -Bangalore- Chennai(slot wise) 38 ____________________________________________________asci research and consultancy iii Competition Issues in the Air Transport Sector in India List of Figures Figure Title Page No. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH TUESDAY, THE 25 OCTOBER 2016 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 61 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 62 TO 67 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 68 TO 79 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 80 TO 91 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 25.10.2016 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE JAYANT NATH AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS FOR FINAL HEARING ______________________________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 7334/2015 RELIANCE POWER LIMITED & ORS MAHESH AGARWAL,PRADEEP CM APPL. 13473/2015 Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS AGGARWAL,SANJEEV NARULA CM APPL. 3686/2016 CM APPL. 8963/2016 PH / AT 2.15 P.M. 25.10.2016 COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS.JUSTICE SANGITA DHINGRA SEHGAL FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. LPA 560/2016 AJIT SINGH V P RANA CM APPL. 37776/2016 Vs. GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI & CM APPL. 37777/2016 ORS 2. W.P.(C) 5679/2016 MASTER ARJUN ANAND DR. M K GAHLAUT,ASHOK KUMAR Vs. CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION & ANR. AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 3. LPA 835/2015 SANJEEV KUMAR RAJBIR BANSAL & SUNIL CM APPL. 27424/2015 Vs. INDIAN OIL CORPORATION KUMAR,MALA NARAYAN CM APPL. 27426/2015 LTD & ANR 4. LPA 332/2016 CHANCHAL JAIN CHANCHAL JAIN,AMIT Vs. MINES SECRETARY UNION OF MAHAJAN,ARUN KUMAR SRIVASTAVA INDIA & ANR 5. -

September 2001 Interesting Times CONTENTS He Airline Industry Is Living in Interesting Times, As the Old Tchinese Curse Has It

Aviation Strategy Issue No: 47 September 2001 Interesting times CONTENTS he airline industry is living in interesting times, as the old TChinese curse has it. Analysis There are more and more signs of weakening economies, but the official indicators are not pointing to a recession, ie an absolute down-turn in activity The OECD's mid-year Economic Outlook Industry outlook 1 highlights the slow-down in the US economy from real GDP growth of 5.0% in 2000 to 1.9% this year, though a recovery to 3.1% is Sabena, forced to face expected for 2002. The EU is just slightly down this year - GDP reality 2-3 growth of 2.6% against 3.1% in 2000 - and next year is put at 2.7%. Japan, however, continues to plod along its L-shaped recession - 1.3% in 2000, 1.2% in 2001, 0.7% in 2002. Oneworld and SkyTeam: The airlines that are suffering disproportionately are those that Justifying immunity 4-6 followed strategies of tight capacity curtailment yield enhancement and focus on business travel. The US Majors' second quarter Briefing results were unprecedently bad - an operating loss of $0.8bn against a $2.8bn profit a year ago. BA, according to a widely Embraer: new challenges for reported analysis from Merrill Lynch, will be turning to losses for Brazil’s success story 7-10 2001/02. The reason that the airline downturn is worse than that implied KLM: Still searching for by the economic number probably has a lot to do with the collapse a sustainable role 8-14 of the new technology sector. -

Industrial Reform and Air Transport Development in China

INDUSTRIAL REFORM AND AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Anming Zhang Department of Economics University of Victoria Victoria, BC Canada and Visiting Professor, 1996-98 Department of Economics and Finance City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong Occasional Paper #17 November 1997 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................... i Acknowledgements ............................................................ i I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................1 II. INDUSTRIAL REFORM ....................................................3 III. REFORMS IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY .....................................5 IV. AIR TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT AND COMPETITION .......................7 A. Air Traffic Growth and Route Development ................................7 B. Market Structure and Route Concentration ................................10 C. Airline Operation and Competition ......................................13 V. CONCLUDING REMARKS ................................................16 References ..................................................................17 List of Tables Table 1: Model Split in Non-Urban Transport in China ................................2 Table 2: Traffic Volume in China's Airline Industry ...................................8 Table 3: Number of City-pair Routes in China's Airline Industry .........................8 Table 4: Overview of Chinese Airline Performance, 1980-94 ............................9 Table 5: Traffic Performed by China's Airlines -

LOK SABRA DEBATES (English Version)

Tenth Series, Vol. XLVI, No. 20 Friday, December 22, 1995 Pausa 1, 1917 (Saka' LOK SABRA DEBATES (English Version) Fifteenth Session (Tehth Lok Sabha) I-- (Vol. XLVI contains Nos. 11 to 20) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price " RI. 50.00 · ~ ;t ~ i ~,t;·&4i~"~~~~~t~: CONTENTS (Tenth Series, Vol. XLVI Fifteenth Session, 1995/1917 (Saka) No. 20, Friday, December 22, 1995/Pausa 1, 1917 (Saka) COLUMNS OBITUARY REFERENCE 1-5 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS .. Starred Questions Nos. : 361 to 380 (21.12.95) 5-36 381 to 400 (22.12.95) 36-57 Unstarred Questions Nos. : 3766 to 3972 (21.12.95) 57-288 3973 to 4202 (22.12.95) 288-467 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 468--514 COM~TTEE ON PRIVATE MEMBERS' BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS 514 Minutes of 46th and 47th sitting of the Committee - Laid PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE Hundred-twelfth and One hundred-thirteenth Reports - Presented 514 COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC UNDERTAKINGS Forty-sixth and Forty-seventh Reports and Minutes - Presented 514-515 COMMITTEE ON WELFARE OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES Fifty-fifth and Fifty-seventh Reports - Presl!nted 515 RAILWAY CONVENTION COMMITTEE Eleventh Report - Presented 515 JOINT COMMITTEE ON OFFICES OF PROFIT Tenth, Eleventh and Twelfth Reports - Presented 516 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS Twenty-fifth Report - Presented 516 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS Minutes of 49th to 66th sittings of the Committee - Laid 516 COMMITTEE ON SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION Twenty-first, Twenty-second and Twenty-third Reports - Presented 516 COMMITTEE ON PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE Twenty-first and Twenty-second Reports -

Aviation Industry in India

Aviation BUSINESS ANAYISIS AND PRESENTAION TOPIC: - AVIATION INDUSTRY IN INDIA SUBMITED TO: - Prof. S K Biswal Date of Presentation:-15thMarch, 2014 SUBMITTED BY:-Group no – 20 Amit Kumar Singh - 1306260035 Pooja Singh - 1306260020 Rourkela Institute of Management Studies, Rourkela 0 Aviation MBA 1st year (2nd SEM) Rourkela Institute of Management Studies, Rourkela 1 Aviation ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I have made lot of efforts to make this project. However, it would not have been possible without the kind support and help of many individuals who helped me in completing this project report i would like to extend my sincere thanks to all of them. I would like to thank our faculty Prof: S.K BISWAL for his guidance and help to complete my project. I would also like to thank my friends and family for their co-operation and encouragement which help me in completing this project. Rourkela Institute of Management Studies, Rourkela 2 Aviation Executive Summary India is one of the fastest growing aviation markets in the world. With the liberalization of the Indian aviation sector, the industry had witnessed a transformation with the entry of the privately owned full service airlines and low cost carriers. The sector has seen a significant increase in number of domestic air travel passengers. Some of the factors that have resulted in higher demand for air transport in India include the growing middle class and its purchasing power, low airfares offered by low cost carriers, the growth of the tourism industry in India, increasing outbound travel from India, and the overall economic growth of india. Rourkela Institute of Management Studies, Rourkela 3 Aviation CONTENTS Chapters Page no. -

Acquisitions, Mergers, Joint-Ventures, Alliances, Partnerships and Other Business Combinations, a Study of TATA Sons, Their Jour

IARJSET ISSN (O) 2393-8021, ISSN (P) 2394-1588 International Advanced Research Journal in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 8, Issue 8, August 2021 DOI: 10.17148/IARJSET.2021.8867 Acquisitions, Mergers, Joint-Ventures, Alliances, Partnerships and other Business Combinations, a study of TATA Sons, their journey, impacts and strategies for the Airline Industry Shaheed Khan1, Freeda Maria Swarna M2, R. Kannan3, S. Praveen Kumar3 Research Scholar, Centre for Tourism and Hotel Management, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, India1 Research Scholar, Centre for Tourism and Hotel Management, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, India2 Professor and Director, Centre for Tourism and Hotel Management, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, India 3 Assistant Professor, Centre for Tourism and Hotel Management, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, India4 Abstract: Aviation Industry has held its stead and ensured corporate business across the world. India saw the growth of airlines from the beginning of the twentieth century albeit, in the private sector, India also witnessed Nationalization followed by privatization. With a multitude of domestic and global players, aviation in India grew leaps and bounds. Many private airlines wound up on various accounts, many were born as well. The Government of India ensured that Air India and its subsidiaries which were successful till the 1970s and were losing steam on account of bureaucratic and political apathy was funding the behemoth, which turned out to be a loss-making enterprise. The world of aviation has seen plenty of Acquisitions, Mergers, Joint-ventures, Alliances, Partnerships and other business combinations as researched and studied by Prof. Benjamin Gomes-Casseres in his Remix Strategy. The Research paper is a work in progress which is focusing on the dynamics of what the TATA Sons are doing to ensure a revert back to the business that they originally founded in 1932. -

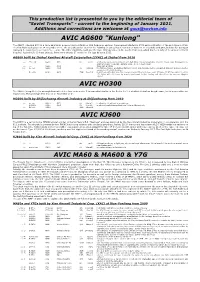

AVIC AG600 "Kunlong"

This production list is presented to you by the editorial team of "Soviet Transports" - current to the beginning of January 2021. Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected] AVIC AG600 "Kunlong" The AG600 (Jiaolong 600) is a large amphibian powered by four Zhuzhou WJ6 turboprop engines. Development started in 2009 and construction of the prototype in 2014. The first flight took place on 24 December 2017. The aircraft can be used for fire-fighting (it can collect 12 tonnes of water in 20 seconds) and SAR, but also for transport (carrying 50 passengers over up to 5,000 km). The latter capability could give the type strategic value in the South China Sea, which has been subject to various territorial disputes. According to Chinese sources, there were already 17 orders for the type by early 2015. AG600 built by Zhuhai Yanzhou Aircraft Corporation (ZYAC) at Zhuhai from 2016 --- 'B-002A' AG600 AVIC ph. nov20 a full-scale mock-up; in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; displayed in the Jingmen Aviator Town (N30.984289 E112.087750), seen nov20 --- --- AG600 AVIC static test airframe 001 no reg AG600 AVIC r/o 23jul16 the first prototype; production started in 2014, mid-fuselage section completed 29dec14 and nose section completed 17mar15; in primer B-002A AG600 AVIC ZUH 30oct16 in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; f/f 24dec17; f/f from water 20oct18; 172 flights with 308 hours by may20; performed its first landing and take-off on the sea near Qingdao 26jul20 AVIC HO300 The HO300 (Seagull 300) is an amphibian with either four or six seats.