The Fleets of the First Punic War Author(S): W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carthage and Rome; and the Regulations About Them Are Precise

Conditions and Terms of Use PREFACE Copyright © Heritage History 2010 It is difficult to tell the story of Carthage, Some rights reserved because one has to tell it without sympathy, and from the This text was produced and distributed by Heritage History, an standpoint of her enemies. It is a great advantage, on the organization dedicated to the preservation of classical juvenile history other hand, that the materials are of a manageable books, and to the promotion of the works of traditional history authors. amount, and that a fairly complete narrative may be The books which Heritage History republishes are in the public given within a moderate compass. domain and are no longer protected by the original copyright. They may therefore be reproduced within the United States without paying a royalty I have made it a rule to go to the original to the author. authorities. At the same time I have to express my The text and pictures used to produce this version of the work, obligations to several modern works, to the geographical however, are the property of Heritage History and are subject to certain treatises of Heeren, the histories of Grote, Arnold and restrictions. These restrictions are imposed for the purpose of protecting the Mommsen, Mr. Bosworth Smith's admirable Carthage integrity of the work, for preventing plagiarism, and for helping to assure and the Carthaginians, and the learned and exhaustive that compromised versions of the work are not widely disseminated. History of Art in Phoenicia and its Dependencies, by In order to preserve information regarding the origin of this text, a Messieurs Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, as copyright by the author, and a Heritage History distribution date are translated and edited by Mr. -

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

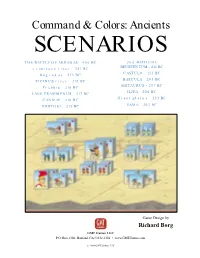

Command & Colors: Ancients SCENARIOS

Command & Colors: Ancients 1 Command & Colors: Ancients SCENARIOS THE BATTLE OF AKRAGAS – 406 BC 2nd BATTLE OF BENEVENTUM - 214 BC crimissos river – 341 BC CASTULO – 211 BC bagradas – 253 BC BAECULA – 208 BC TICINUS river – 218 BC METAURUS - 207 BC Trebbia – 218 BC ILIPA – 206 BC LAKE TRASIMENUS – 217 BC Great plains – 203 BC CANNAE – 216 BC DERTOSA – 215 BC ZAMA – 202 BC Game Design by Richard Borg GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 • www.GMTGames.com © 2006 GMT Games, LLC 2 Command & Colors: Ancients THE BATTLE OF AKRAGAS – 406 BC CARTHAGINIAN Mago Himilco MA HM A AA LC CH LB L CH LB LB L LC A H H H H A A MC Daphnaeus Dionysius SYRACUSAN Historical Background War Council It is a time of violent competition between the Syracusan Ty- Carthagian Army rants (military dictators) and Carthage for control of Sicily. The • Leader: Himilco Carthaginians under Himilco have besieged Akragas, a city al- • 5 Command Cards lied with Syracuse, prompting Daphnaeus and his army to march to its aid. The Carthaginians split their army into an observation Syracusan Army force in front of Akragas, and a blocking force sent to oppose • Use Roman blocks Daphnaeus. The Carthaginian army was almost totally merce- • Leader: Daphnaeus nary, while Daphnaeus’s contained veteran heavy infantry that • 6 Command Cards proved invincible when committed to the battle. The survivor’s • Move First of Himilco’s badly beaten army fled to the coastal fort shelter- Victory ing Mago’s observation force. There was no pursuit and no fur- 5 Banners ther battle. -

Ancient Rome – Wars and Battles the Ancient Romans Fought Many Battles and Wars in Order to Expand and Protect Their Empire

Ancient Rome – Wars and Battles The Ancient Romans fought many battles and wars in order to expand and protect their empire. There were also civil wars where Romans fought Romans in order to gain power. Here are some of the major battles and wars that the Romans fought. The Punic Wars The Punic Wars were fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 BC to 146 BC. Carthage was a large City located on the coast of North Africa. This sounds like a long way away at first, but Carthage was just a short sea voyage from Rome across the Mediterranean Sea. Both cities were major powers at the time and both were expanding their empires. As the empires grew, they began to clash and soon war had begun. There were three major parts of the Punic wars and they were fought over the course of more than 100 years, First Punic War (264 - 241 BC): The First Punic War was fought largely over the island of Sicily. This meant a lot of the fighting was at sea where Carthage had the advantage of a much stronger navy than Rome. However, Rome quickly built up a large navy of over 100 ships. Rome also invented the corvus, a type of assault bridge that allowed Rome's superior soldiers to board enemy navy vessels. Rome soon dominated Carthage and won the war. Second Punic War (218 - 201 BC): In the Second Punic War, Carthage had more success fighting against the Roman legions. The Carthage leader and general, Hannibal, made a daring crossing of the Alps to attack Rome and northern Italy. -

The Roman Army's Emergence from Its Italian Origins

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE ROMAN ARMY’S EMERGENCE FROM ITS ITALIAN ORIGINS Patrick Alan Kent A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Richard Talbert Nathan Rosenstein Daniel Gargola Fred Naiden Wayne Lee ABSTRACT PATRICK ALAN KENT: The Roman Army’s Emergence from its Italian Origins (Under the direction of Prof. Richard Talbert) Roman armies in the 4 th century and earlier resembled other Italian armies of the day. By using what limited sources are available concerning early Italian warfare, it is possible to reinterpret the history of the Republic through the changing relationship of the Romans and their Italian allies. An important aspect of early Italian warfare was military cooperation, facilitated by overlapping bonds of formal and informal relationships between communities and individuals. However, there was little in the way of organized allied contingents. Over the 3 rd century and culminating in the Second Punic War, the Romans organized their Italian allies into large conglomerate units that were placed under Roman officers. At the same time, the Romans generally took more direct control of the military resources of their allies as idea of military obligation developed. The integration and subordination of the Italians under increasing Roman domination fundamentally altered their relationships. In the 2 nd century the result was a growing feeling of discontent among the Italians with their position. -

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) the Punic Wars

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) The Punic Wars After subjugating the Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome sought to control western Mediterranean trade. Its chief rival, located across the Mediterranean in northern Africa, was the city-state of Carthage. Originally a Phoenician colony, Carthage had become a powerful commercial empire. Rome defeated Carthage in three Punic (Phoenician) Wars and gained mastery of the western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.) Fighting chiefly on the island of Sicily and in the Mediterranean Sea, Rome’s citizen-soldiers eventually defeated Carthage’s mercenaries(hired foreign soldiers). Rome annexed Sicily and then Sardinia and Corsica. Both sides prepared to renew the struggle. Carthage acquired a part of Spain and recruited Spanish troops. Rome consolidated its position in Italy by conquering the Gauls, thereby extending its rule northward from the Po River to the Alps. The Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) Hannibal, Carthage’s great general, led an army from Spain across the Alps and into Italy. At first he won numerous victories, climaxed by the battle of Cannae. However, he was unable to seize the city of Rome. Gradually the tide of battle turned in favor of Rome. The Romans destroyed a Carthaginian army sent to reinforce Hannibal, then conquered Spain, and finally invaded North Africa. Hannibal withdrew his army from Italy to defend Carthage but, in the Battle of Zama, was at last defeated. Rome annexed Carthage’s Spanish provinces and reduced Carthage to a second-rate power. Hannibal of Carthage Reasons for Rome’s Victory • superior wealth and military power, • the loyalty of most of its allies, and • the rise of capable generals, notably Fabius and Scipio. -

Warships of the First Punic War: an Archaeological Investigation

WARSHIPS OF THE FIRST PUNIC WAR: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION AND CONTRIBUTORY RECONSTRUCTION OF THE EGADI 10 WARSHIP FROM THE BATTLE OF THE EGADI ISLANDS (241 B.C.) by Mateusz Polakowski April, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. David J. Stewart Major Department: Program in Maritime Studies of the Department of History Oared warships dominated the Mediterranean from the Bronze Age down to the development of cannon. Purpose-built warships were specifically designed to withstand the stresses of ramming tactics and high intensity impacts. Propelled by the oars of skilled rowing crews, squadrons of these ships could work in unison to outmaneuver and attack enemy ships. In 241 B.C. off the northwestern coast of Sicily, a Roman fleet of fast ramming warships intercepted a Carthaginian warship convoy attempting to relieve Hamilcar Barca’s besieged troops atop Mount Eryx (modern day Erice). The ensuing naval battle led to the ultimate defeat of the Carthaginian forces and an end to the First Punic War (264–241 B.C.). Over the course of the past 12 years, the Egadi Islands Archaeological Site has been under investigation producing new insights into the warships that once patrolled the wine dark sea. The ongoing archaeological investigation has located Carthaginian helmets, hundreds of amphora, and 11 rams that sank during the course of the battle. This research uses the recovered Egadi 10 ram to attempt a conjectural reconstruction of a warship that took part in the battle. It analyzes historical accounts of naval engagements during the First Punic War in order to produce a narrative of warship innovation throughout the course of the war. -

Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity Kevin Patrick Emery Wofford College

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Student Scholarship 5-2016 Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity Kevin Patrick Emery Wofford College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Emery, Kevin Patrick, "Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity" (2016). Student Scholarship. Paper 11. http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/studentpubs/11 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wofford College Carthaginian Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, Allied Conscripts, and Multi-Ethnic Armies in Antiquity An Honors Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the Department of History In Candidacy For An Honors Degree in History By Kevin Patrick Emery Spartanburg, South Carolina May 2016 1 Introduction The story of the mercenary armies of Carthage is one of incompetence and disaster, followed by clever innovation. It is a story not just of battles and betrayal, but also of the interactions between dissimilar peoples in a multiethnic army trying to coordinate, fight, and win, while commanded by a Punic officer corps which may or may not have been competent. Carthaginian mercenaries are one piece of a larger narrative about the struggle between Carthage and Rome for dominance in the Western Mediterranean, and their history illustrates the evolution of the mercenary system employed by the Carthaginian Empire to extend her power and ensure her survival. -

Carthage and Tunis, the Old and New Gates of the Orient

^L ' V •.'• V/ m^s^ ^.oF-CA < Viiiiiiiii^Tv CElij-^ frt ^ Cci Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from < IVIicrosoft Corporation f.]IIBR, -^'.^ ;>J0^ r\f •lALIFOff^/, =3 %WJ. # >? slad. http://www.archive.org/details/carthagetunisold(Jl :hhv ^i. I)NIVER% ^ylOSMElfr^^ >^?S(f •Mmv^ '''/iawiNMW^ J ;; ;ijr{v'j,!j I ir^iiiu*- ^AUii ^^WEUNIVERS/, INJCV '"MIFO/?^ ^5WrUNIVER% CARTHAGE AND TUNIS VOL. 1 Carthaginian vase [Delattre). CARTHAGE AND TUNIS THE OLD AND NEfF GATES OF THE ORIENT By DOUGLAS SLADEN Author of "The Japs at Home," "Queer Things about Japan," *' In Sicily," etc., etc. ^ # ^ WITH 6 MAPS AND 68 ILLUSTRATIONS INCLUDING SIX COLOURED PLATES By BENTON FLETCHER Vol. I London UTCHINSON & CO. ternoster Row # 4» 1906 Carthaginian razors [Delatire). or V. J DeDicateO to J. I. S. WHITAKER, F.Z.S., M.B.O.U. OF MALFITANO, PALERMO AUTHOR OF " THE BIRDS OF TUNISIA " IN REMEMBRANCE OF REPEATED KINDNESSES EXTENDING OVER A PERIOD OF TEN YEARS 941029 (zr Carthaginian writing (Delattre). PREFACE CARTHAGE and Tunis are the Gates of the Orient, old and new. The rich wares of the East found their way into the Mediterranean in the galleys of Carthage, the Venice of antiquity ; and though her great seaport, the Lake of Tunis, is no longer seething with the commerce of the world, you have only to pass through Tunis's old sea-gate to find yourself surrounded by the people of the Bible, the Arabian Nights, and the Alhambra of the days of the Moors. Carthage was the gate of Eastern commerce, Tunis is the gate of Eastern life. -

The Story of Carthage, Because One Has to Tell It Without Sympathy, and from the Standpoint of Her Enemies

li^!*^'*,?*^','. K lA, ZT—iD v^^ )A Cfce ®tor? of tfte iSations. CARTHAGE THE STORY OF THE NATIONS. Large Crown 8vo, Cloth, Illustrated, ^s. 1. ROME. Arthur Oilman, M.A. 2. THE JEWS. Prof. J. K. Hosmer. 3. GERMANY. Rev. S. Baring-Gould, M.A. 4. CARTHAGE. Prof. A. J. Church. 5. ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE. Prof. J. P. Mahaffy. 6. THE MOORS IN SPAIN. Stanley Lane-Poole. 7. ANCIENT EGYPT. Canon Raw- LINSON. 8. HUNGARY. Prof. A. Vambery. 9. THE SARACENS. A. Oilman, M.A. 10. IRELAND. Hon. Emily Lawless. 11. THE GOTHS. Henry Bradley. 12. CHALD^A. Z. A. Ragozin. 13. THE TURKS. Stanley Lane-Poole. 14. ASSYRIA. Z. A. Ragozin. 15. HOLLAND. Prof. J. E. Thorold Rogers. 16. PERSIA. S.W.Benjamin. London ; T. PISHEE UNWIN, 2 6, Paternoster Square, E.G. CARTHAGE OR THE EMPIRE OF AFRICA ALFRED J. CHURCH, M.A. '* PROFESSOR OF LATIN IN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON, AUTHOR OP STORIES FROM HOMER," ETC., ETC. WITH THE COLLABORA TION OF ARTHUR OILMAN, M.A. THIRD EDITION, gtrnhon T. FISHER UNWIN 26 PATERNOSTER SQUARE NEW YORK : O. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MDCCCLXXXVII SEEN BY PRESERVATION SERVICES M } 7 4Q«^ Entered at Stationers' Hall By T. fisher UNWIN. Copyright by G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1886 (For the United States of America), PREFACE. It is difficult to tell the story of Carthage, because one has to tell it without sympathy, and from the standpoint of her enemies. It is a great advantage, on the other hand, that the materials are of a manage- able amount, and that a fairly complete narrative may be given within a moderate compass. -

(Eg Carthage, Hippacra, Tunes, Utica, Hamilcar, Hanno the Great, Mathos, Polybius) Are Not

INDEX Very frequently mentioned names (e.g. Carthage, Hippacra, Tunes, Utica, Hamilcar, Hanno the Great, Mathos, Polybius) are not indexed. HB = Hamilcar Barca Acholla 239 Bizerte, Lac de 102 Acra Leuce (Spain) 255 Bizerte: see Hippacra Ad Gallum Gallinacium 113 boetharchos (area commander) 155 Adherbal (general in Sicily 250–248) Bomilcar (4th Cent.) 15 22–23, 212 Bomilcar (HB’s son-in-law) 21–22, Aegates Islands (battle) xv, 13 233 Agathocles xiii, xiv, 18, 32, 97, Bostar (of\ cer in Sardinia) 155–57, 143–44, 185, 231, 244 272 Alexander the Great 8, 77, 114, 143, Bulla 133, 199, 256 175 Appian xix, 15, 20–21, 26, 32, 51, 85, Campania, Campanians xiv, 7, 26, 42, 102, 110, 127, 129, 149, 244, 255, 48, 66–67, 69, 77–79, 129, 133, 144, 263, 269 155, 273 Aptuca 137 Cape Bon xvi, 82–83, 92, 126, 162, arbitration 56–57, 59–60, 64, 86 183, 192–93, 207–8, 212, 220, 238, Argoub Beïda (ridge) 208 240, 253 Ariana, El 52, 113 Carales (Cagliari) 156 Aristotle xvii, 13–14, 83, 273 Carthalo (admiral 249–248) 9, 22, army of Sicily: see Sicily 212 artillery 33, 38, 61, 97–99, 100, 102, Cassius Dio xix, 129 105, 264 Castra Cornelia (Galaat el Andless) 97 Atilius Regulus, Marcus xiv, xv, 32, Catulus: see Lutatius 124–25, 185, 251 Cercina, isle (Kerkennah) 238–39 Autaritus 42–49, 68, 70–72, 74, 79, Cirta 156, 244 91, 115, 132–36, 141–42, 144, 146, coinage (rebel) 79–80, 91, 139, 150–51, 154, 160–61, 164–65, 140–42, 198–99 168–71, 174, 188, 194, 196, 198, Conon (Athenian general) 29 201–3, 210–11, 213–14, 219, 230, Crétéville 236 246, 265, 271–72 Crimisus -

The Punic Wars Group Magazine Project

THE PUNIC WARS GROUP MAGAZINE PROJECT From 264-146 B.C., a series of wars was fought between Rome and their Mediterranean rival, Carthage. By the end of the third Punic War, Carthage was left in ruins and Rome had established itself as the dominant force in the Mediterranean world. Your group’s task is to detail these three history altering wars in the form of a historical magazine. Below is a list of requirements for this magazine. Individuals within the groups must share the workload evenly. Teamwork is IMPERATIVE!! Projects are due on Monday, April 11th. REQUIREMENTS Cover Page o Magazine Title o Focus Picture with a caption o Individuals names from the group o Inside front cover should be a magazine table of contents 3 Main Articles o Cause/War/Effect of the First Punic War o Cause/War/Effect of the Second Punic War o Cause/War/Effect of the Third Punic War . Articles should include factual information about dates, important people, major battles, and how these wars affected BOTH Rome and Carthage. 1 Interview o You will interview one of the important people from any of the Punic Wars. Interviews must include a minimum of 5 thought provoking questions and detailed responses. Responses are to include factual information and written from the personal perspective/opinion of the person. Groups can interview any of the following. Scipio Africanus . Cato the Elder . Hamilcar Barca . Hannibal Barca . Hasdrubal . A separate person of the group’s choice that played a major role in the Punic Wars 1 Biography o You will create a biography of an important person from the Punic Wars.