Imagining Richard Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Wagner Intoxication

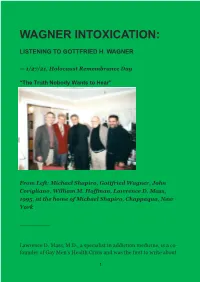

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr

RWVI WAGNER NEWS – Nr. 7 – 01/2018 – deutsch – english – français Wir möchten die Ortsverbände höflich bitten, zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten und Veranstaltungsankündigungen diese Links zu benutzen Link zur Übermittlung von Nachrichten für die RWVI Webseiten: http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-news/ Link zur Übermittlung von Veranstaltungshinweisen für die RWVI Webseiten. http://www.richard-wagner.org/send-event/ Danke für ihre Mithilfe. Liebe Wagnergemeinde weltweit, Das nun zu Ende gehende Jahr 2017 war geprägt von großen politischen Veränderungen, deren Umstände und Auswüchse in den Medien sattsam kritisch gewürdigt wurden. Gleichwohl aber markieren Ereignisse wie wir Sie in einigen Staaten derzeit erleben, Entwicklungen, die wir sicher nicht nur begrüßen. Humanismus, Aufklärung und Gewaltenteilung waren lange Zeit unumstrittene Eckpfeiler unseres Zusammenlebens und Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Henry Dunant, Elihu Root, José Martí oder Yoko Ono mögen exemplarisch als einige, der vielen von uns denkbaren Vorbilder in dieser Hinsicht gelten. Auch Komponisten spielten früher eine gewichtige gesellschaftliche Rolle und repräsentierten oder beeinflussten die Menschen in ihrem Handeln. Gerade die Tatsache aber, dass Musik heute fast ohne Ausnahme zum gesichtslosen Konsumartikel geworden ist, sagt viel aus. Wen würden Sie heute als eine „große Persönlichkeit“ mit bedeutendem Einfluss unter den lebenden Komponisten bezeichnen? Große Persönlichkeiten waren und sind aber meist nicht unumstritten, biographische Brüche und punktuelles Versagen gehören zum Leben leider dazu. Richard Wagner ist hierfür ein beredtes Beispiel und wir alle kennen die Angriffsflächen, die unser vielseitiger und viel produzierender Meister bis heute bietet. Geschichte ist leider ebenso wenig abzuändern wie eben diese Schattenseiten des Genies. Die Zeit bleibt nicht stehen und wir sollten gerade bei Richard Wagner immer vor allem und immer wieder neu auf die Taten in Form seiner ewig gültigen Musikdramen blicken, die eben genau das Gegenteil einer Blaupause für die aktuellen Entwicklungen sind. -

Notes on Wagner's Ring Cycle

THE RING CYCLE BACKGROUND FOR NC OPERA By Margie Satinsky President, Triangle Wagner Society April 9, 2019 Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle includes four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walkure, Siegfried, and Gotterdammerung. What’s so special about the Ring Cycle? Here’s what William Berger, author of Wagner without Fear, says: …the Ring is probably the longest chunk of music and/or drama ever put before an audience. It is certainly one of the best. There is nothing remotely like it. The Ring is a German Romantic view of Norse and Teutonic myth influenced by both Greek tragedy and a Buddhist sense of destiny told with a sociopolitical deconstruction of contemporary society, a psychological study of motivation and action, and a blueprint for a new approach to music and theater.” One of the most fascinating characteristics of the Ring is the number of meanings attributed to it. It has been seen as a justification for governments and a condemnation of them. It speaks to traditionalists and forward-thinkers. It is distinctly German and profoundly pan-national. It provides a lifetime of study for musicologists and thrilling entertainment. It is an adventure for all who approach it. SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE RING CYCLE Wagner was extremely critical of the music of his day. Unlike other composers, he not only wrote the music and the libretto, but also dictated the details of each production. The German word for total work of art, Gesamtkunstwerk, means the synthesis of the poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts with music subsidiary to drama. As a composer, Wagner was very interested in themes, and he uses them in The Ring Cycle in different ways. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Circling Opera in Berlin by Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College

Circling Opera in Berlin By Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College, 2001 A.M., Brown University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in the Department of Music at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 This dissertation by Paul Martin Chaikin is accepted in its present form by the Department of Music as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_______________ _________________________________ Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Jeff Todd Titon, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Philip Rosen, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Dana Gooley, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Deutsche Akademische Austauch Dienst (DAAD) for funding my fieldwork in Berlin. I am also grateful to the Institut für Musikwissenschaft und Medienwissenschaft at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin for providing me with an academic affiliation in Germany, and to Prof. Dr. Christian Kaden for sponsoring my research proposal. I am deeply indebted to the Deutsche Staatsoper Unter den Linden for welcoming me into the administrative thicket that sustains operatic culture in Berlin. I am especially grateful to Francis Hüsers, the company’s director of artistic affairs and chief dramaturg, and to Ilse Ungeheuer, the former coordinator of the dramaturgy department. I would also like to thank Ronny Unganz and Sabine Turner for leading me to secret caches of quantitative data. Throughout this entire ordeal, Rose Rosengard Subotnik has been a superlative academic advisor and a thoughtful mentor; my gratitude to her is beyond measure. -

Gesamttext Als Download (PDF)

DER RING DES NIBELUNGEN Bayreuth 1976-1980 Eine Betrachtung der Inszenierung von Patrice Chéreau und eine Annäherung an das Gesamtkunstwerk Magisterarbeit in der Philosophischen Fakultät II (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg vorgelegt von Jochen Kienbaum aus Gummersbach Der Ring 1976 - 1980 Inhalt Vorbemerkung Im Folgenden wird eine Zitiertechnik verwendet, die dem Leser eine schnelle Orientierung ohne Nachschlagen ermöglichen soll und die dabei gleichzeitig eine unnötige Belastung des Fußnotenapparates sowie über- flüssige Doppelnachweise vermeidet. Sie folgt dem heute gebräuchlichen Kennziffernsystem. Die genauen bibliographischen Daten eines Zitates können dabei über Kennziffern ermittelt werden, die in Klammern hinter das Zitat gesetzt werden. Dabei steht die erste Ziffer für das im Literaturverzeichnis angeführte Werk und die zweite Ziffer (nach einem Komma angeschlossen) für die Seitenzahl; wird nur auf eine Seitenzahl verwiesen, so ist dies durch ein vorgestelltes S. erkenntlich. Dieser Kennziffer ist unter Umständen der Name des Verfassers beigegeben, soweit dieser nicht aus dem Kontext eindeutig hervorgeht. Fußnoten im Text dienen der reinen Erläuterung oder Erweiterung des Haupttextes. Lediglich der Nachweis von Zitaten aus Zeitungsausschnitten erfolgt direkt in einer Fußnote. Beispiel: (Mann. 35,145) läßt sich über die Kennziffer 35 aufschlüs- seln als: Thomas Mann, Wagner und unsere Zeit. Aufsätze, Betrachtungen, Briefe. Frankfurt/M. 1983. S.145. Ausnahmen - Für folgende Werke wurden Siglen eingeführt: [GS] Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen in zehn Bän- den. Herausgegeben von Wolfgang Golther. Stuttgart 1914. Diese Ausgabe ist seitenidentisch mit der zweiten Auflage der "Gesammelten Schriften und Dichtungen" die Richard Wagner seit 1871 selbst herausgegeben hat. Golther stellte dieser Ausgabe lediglich eine Biographie voran und einen ausführlichen Anmerkungs- und Registerteil nach. -

Richard Wagner Tristan Und Isolde Wolfgang Sawallisch

Richard Wagner Tristan und Isolde LIVE Windgassen · Nilsson Hoffmann · Saedén · Greindl Chor und Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele Wolfgang Sawallisch ORFEO D’OR Live Recording 26. Juli 1958 „Bayreuther Festspiele Live“. Das Inte- resse der Öffentlichkeit daran ist groß, die Edition erhielt bereits zahlreiche in- ternationale Preise. Die Absicht aller Be- teiligten ist nichts weniger als Nostalgie oder eine Verklärung der Vergangen- Das „neue Bayreuth“, wie es seit 1951 heit, vielmehr die spannende Wieder- von Wieland und Wolfgang Wagner be- entdeckung großartiger Momente der gründet und erfolgreich etabliert wur- Festspiele. Die sorgfältig erarbeitete de, suchte von Anfang an gezielt die Herausgabe der Mitschnitte soll erin- Vermittlung durch die damals existie- nern und vergegenwärtigen helfen, renden Medien, vor allem den Hörfunk indem musikalische Highlights aus der und die Schallplatte. Die Live-Übertra- Aufführungsgeschichte der Bayreuther gungen im Bayerischen Rundfunk und Festspiele wieder zugänglich gemacht angeschlossenen Sendern in Deutsch- und nacherlebbar werden. land, Europa und Übersee entwickelten sich binnen kurzer Zeit zu einem festen Bestandteil der alljährlichen Festspiele – und sind es bis heute geblieben. Nicht Katharina Wagner, zuletzt wird dadurch vielen Wagneren- Festspielleitung thusiasten weltweit eine zumindest akustische Teilnahme am Festspielge- schehen ermöglicht. Zugleich wurden Since its inception in 1951, ‚New Bay- und werden damit die künstlerischen reuth‘, founded and successfully run Leistungen der -

In Association With

OVERTURE OPERA GUIDES in association with We are delighted to have the opportunity to work with Overture Publishing on this series of opera guides and to build on the work English National Opera did over twenty years ago on the Calder Opera Guide Series. As well as reworking and updat- ing existing titles, Overture and ENO have commissioned new titles for the series and all of the guides will be published to coincide with repertoire being staged by the company at the London Coliseum. We hope that these guides will prove an invaluable resource now and for years to come, and that by delving deeper into the history of an opera, the poetry of the libretto and the nuances of the score, readers’ understanding and appreciation of the opera and the art form in general will be enhanced. John Berry, CBE Artistic Director, ENO The publisher John Calder began the Opera Guides series under the editorship of the late Nicholas John in associa- tion with English National Opera in 1980. It ran until 1994 and eventually included forty-eight titles, covering fifty-eight operas. The books in the series were intended to be companions to the works that make up the core of the operatic repertory. They contained articles, illustrations, musical examples and a complete libretto and singing translation of each opera in the series, as well as bibliographies and discographies. The aim of the present relaunched series is to make available again the guides already published in a redesigned format with new illustrations, some newly commissioned articles, updated reference sections and a literal translation of the libretto that will enable the reader to get closer to the meaning of the origi- nal. -

Reflections on the Stuttgart Ring

Performance The Stuttgart Ring on DVD: A Review Portfolio Everyday Totalitarianism: Reflections on the Stuttgart Ring Downloaded from By the standards of contemporary German opera, the recent Stuttgart production of Richard Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen has generated a great deal of hype. Critics hail it as an epochal “milestone in the history of Wagner production, akin to the Patrice Che´reau Bayreuth centenary Ring of 1976,” and praise it for single- handedly disproving “widespread claims that opera is dead.”1 The most com- http://oq.oxfordjournals.org monly cited virtue of the production is its use of a different director for each opera. Klaus Zehelein, Intendant of the Stuttgart Staatsoper from 1991 to 2006, a dramaturge by profession and the man who organized this Ring, offers unabashed self-praise: “Only because we arranged for a different team to direct each piece of the Ring will its moments of exposition finally realize those sublime theatrical forms that Wagner offers us.”2 The result is now available on DVD. at Princeton University on June 17, 2010 *** Why four directors and not one? Zehelein’s most straightforward justification, the one that dominates press releases from Stuttgart and reviews in the German press, is that stage directors must be liberated. Any effort to impose a unified concept or meaning on the Ring cycle (Totalita¨tsanspruch), Zehelein argues, restricts the director’s creative freedom and is thus “totalitarian.”3 Holistic con- cepts encumber directors by constraining them to adopt interpretations of the Ring consistent with the overarching ideas, symbols, and musical leitmotifs in Wagner’s text and music.4 By treating the Ring instead as a series of disconnected episodes, directors are free to respond to each dramatic moment without “prior assumptions” or “obligations.”5 A modern audience should similarly perceive the Ring as a series of disconnected theatrical moments or “theatrical piecework.”6 Having no big message to transmit and no one in charge enhances artistic freedom and releases creative energy. -

De Muzikale Geschiedenis Van De Bayreuther Festspiele Afl. 22

De muzikale geschiedenis van de Bayreuther Festspiele afl. 22 De Jahrhundert - Ring 1976 door Johan Maarsingh In 1976 was het een eeuw geleden dat de wereldpremière plaatsvond van de Ring des Nibelungen in het Festspielhaus in Bayreuth. Het was in 1976 dus ook honderd jaar geleden dat de eerste Bayreuther Festspiele plaatsvonden. Het kon niet anders of het festival moest in dit jaar een geheel nieuwe productie bieden van de Ring. Het werd een sensationele gebeurtenis, die uitzonderlijke reacties los maakten bij het publiek dat toen gewoon was de Festspiele te bezoeken. Wolfgang Wagner, sinds 1967 de artistiek leider van het jaarlijkse Wagner Festival, had de productie van deze nieuwe Ring in handen gegeven van vier Fransmannen die ook nog eens geen ervaring hadden met Wagners Magnum Opus. Dirigent Pierre Boulez had vanaf 1966 in Bayreuth Parsifal gedirigeerd. Wieland Wagner had hem indertijd naar het Festspielhaus gehaald nadat zij elders in Duitsland hadden samengewerkt in Wozzeck van Alban Berg. Helaas lag Wieland ernstig ziek in het ziekenhuis tijdens de Festpiele van 1966. Op 17 oktober van dat jaar overleed hij. Vanaf 1967 had Wolfgang de artistieke leiding over het festival. In 1970 dirigeerde Boulez zijn laatste Parsifal in Bayreuth, en de op plaat uitgebrachte live-opname werd zijn eerste opname voor Deutsche Grammophon. Enkele jaren later onderhandelde Wolfgang Wagner met Boulez over de mogelijkheid om de nieuwe productie van de Ring te dirigeren. Boulez mocht zelf een regisseur vragen. Gedurende zes voorgaande jaren had Wolfgang in eigen huis zijn tweede Ring aan het publiek getoond maar in 1976 zou alles anders moeten. -

Imagining the West in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union PITT SERIES in RUSSIAN and EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES

Imagining the West in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union PITT SERIES IN RUSSIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES Jonathan Harris, Editor KRITIKA HISTORICAL STUDIES IMAGINING THE WEST IN EASTERN EUROPE AND THE SOVIET UNION EDITED BY GYÖRGY PÉTERI University of Pittsburgh Press Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260 Copyright © 2010, University of Pittsburgh Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Imagining the West in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union / edited by György Péteri. p. cm. — (Pitt series in Russian and East European studies) (Kritika historical studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8229-6125-3 (paper : alk. paper) 1. Europe, Eastern—Relations—Western countries. 2. Russia—Relations—Western countries. 3. Soviet Union—Relations—Western countries. 4. Western countries— Relations—Europe, Eastern. 5. Western countries—Relations—Russia. 6. Western countries—Relations—Soviet Union. 7. Geographical perception—Europe, Eastern— History. 8. Geographical perception—Soviet Union—History. 9. East and West. 10. Transnationalism. I. Péteri, György. DJK45.W47I45 2010 303.48'24701821—dc22 2010031525 CONTENTS Chapter 1. Introduction: The Oblique Coordinate Systems of Modern Identity 1 GyörGy Péteri Chapter 2. Were the Czechs More Western Than Slavic? Nineteenth-Century Travel Literature from Russia by Disillusioned Czechs 13 Karen GammelGaard Chapter 3. Privileged Origins: “National Models” and Reforms of Public Health in Interwar Hungary 36 EriK inGebriGtsen Chapter 4. Defending Children’s Rights, “In Defense of Peace”: Children and Soviet Cultural Diplomacy 59 Catriona Kelly Chapter 5.