Reflections on the Stuttgart Ring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Staatsoper Stuttgart Wird Temporär Zum Online-Opernhaus

Pressemitteilung Stuttgart, 21. April 2020 Staatsoper Stuttgart wird temporär zum Online-Opernhaus Oper trotz Corona: Filmstudio auf der Bühne des Opernhauses eingerichtet; Die Staatsoper Stuttgart setzt ihr digitales On- Demand-Programm mit Unterstützung der LBBW mit Mefistofele und Satyagraha fort Die behördlichen Verordnungen zur Eindämmung der Verbreitung des Corona- Virus wurden bis zum 3. Mai 2020 verlängert. Dies bedeutet, dass mindestens bis zu diesem Datum auch keine Vorstellungen in den Spielstätten der Staatstheater Stuttgart stattfinden. Das Internet wird also, wie bereits in den vergangenen Wochen, zur zentralen Bühne für die Staatsoper Stuttgart: „Wir lassen uns von dieser misslichen Situation nicht unterkriegen – und spielen weiter, natürlich unter Berücksichtigung aller hygienischen Vorgaben und in ständigem Austausch mit dem Amtsarzt. Dass so viele Künstler*innen des Ensembles aus freien Stücken ein so vielfältiges Programm entwickeln, dass durch die Arbeit der Ton- und Videoabteilung analoge Kunst auch digital erfahrbar wird, macht mich sehr glücklich“, so Opernintendant Viktor Schoner. Die Mitarbeiter*innen der Ton- und Videoabteilung der Staatstheater Stuttgart haben in den vergangenen Wochen ein Film- und Tonstudio auf der Bühne des Opernhauses eingerichtet. So schafft die Staatsoper durch die Unterstützung ihres Digitalpartners, der LBBW, eine Infrastruktur, die es auch längerfristig ermöglicht, dem Publikum als Online-Opernhaus zugänglich zu sein: In 12 Stunden pro Woche werden aktuell Videos mit Künstler*innen der Staatsoper, des Staatsorchesters und des Staatsopernchors für das Programm „Oper trotz Corona“ produziert. Geplant sind zudem dramaturgische oder kleinere szenische Formate. Generalmusikdirektor Cornelius Meister dirigierte bereits ein Konzert mit Mitgliedern des Staatsorchesters – die Musiker*innen allesamt in jeweils einer Laube des ersten Rangs verteilt und durch Wände voneinander getrennt. -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

F' ~I!~~ Disc Edition TCO93-75

NEW PUBLICATIONS ARTICLES Block. Geoffrey. 'The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal." Journal ofMusicology 11, no. 4 (Fall 1993): 525-544. Brooks,Jeanice R. "Nadia Boulanger and the Salon ofthe Princesse de Polignac." Journal ofthe American Musicological Society 46, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 415-468. Dtimling, Albrecht. "Hearing, Speaking, Singing, Writing: The Meaning of Oral Tradi tion for Bert Brecht." In Music and Gennan Literature: Their Relationship Since the Middle Ages, edited by James M. McGiathery, 31~326. Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1992. Krabbe, Niels. "Pris Kulden, M0rket Og Fordrervet: Requiem for 20'ernes Berlin." In Musikken Har Ordet: 36 Musikalske Studier, redigeret af Finn Gravesen, 133-142. Copenhagen: Gads Forlag, 1993. Lipman, Samuel. ''Wby Kurt Weill?" In Music and More: Essays, 1975-1991. By Samuel Lipman, 3~49. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1992. Margry, Karel. "'Theresienstadt' (1944-1945):The Nazi Propaganda Film Depicting the Concentration Camp as Paradise." Historical Journal ofFilm, Radio and Television 12, no. 2 (1992): 145-162. [A Gennan version appeared in: Kamy, Miroslav, ed. 11ieresienstadt: Jn der "Endlosung der Judenfrage." Prag: Panorama, 1992.) Schebera, Ji.irgen. '"Meine Tage in Dessau sind gezahlt .. .': Kurt Weill in Briefen aus seiner Vaterstadt." Dessauer Ka/ender 37 (1993): 18-24. Taruskin, Richard. 'The Golden Age ofKitsch: The Seductions and Betrayals ofWeimar Opera." The New Republic (21 March 1994): 28-36. BOOKS Green, Paul. A Southern life: Letters ofPaul Green: 1916-1981. Edited by Laurence G. Avery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1994. Murphy, Donna B. and Stephen Moore. Helen Hayes: A Bio-Bibliography. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

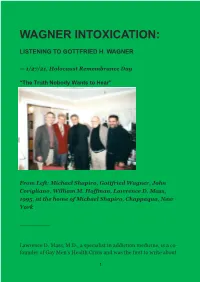

Wagner Intoxication

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

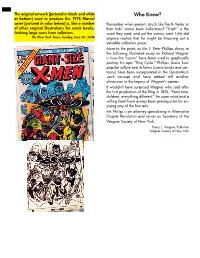

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

WAGNER Die Walküre

660172-74 bk Walküre US 17/7/06 10:28 Page 16 3 CDs Recorded at the Staatsoper Stuttgart, Germany, WAGNER on 29th September 2002 and 2nd January 2003. General Director: Prof. Klaus Zehelein Die Walküre Executive Producers: Dr Reinhard Ermen (SWR Radio), Gambill • Jun • Rootering • Denoke • Behle • Vaughn Dr Dietrich Mack (SWR TV) and Paul Smaczny (EuroArts) Staatsoper Stuttgart • Staatsorchester Stuttgart Producer: Thomas Angelkorte Editor: Irmgard Bauer Lothar Zagrosek Engineers: Brigitte Hermann and Karl-Heinz Runde This performance of Die Walküre is the second part of Wagner’s Ring cycle recorded live during Stuttgart Opera’s 2002/2003 season. For the first time in the history of the Ring cycle each of the four operas was staged with separate producers and casts. A production of EuroArts Music International GmbH and Südwestrundfunk in co-operation with ARTE Gefördert von der Medien- und Filmgesellschaft Baden-Württemberg 8.660172-74 16 660172-74 bk Walküre US 17/7/06 10:28 Page 2 Die Walküre Stuttgart Staatsorchester (The Valkyrie) Established in 1589 as the Court Orchestra of Württemberg, the Württemberg Stuttgart State Orchestra has a history The First Day of over four hundred years. Over the generations there have been collaborations with musicians of distinction, among them Leonhard Lechner, the Frobergers, Niccolò Jommelli, Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg, Konradin Kreutzer, of Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Carl Maria von Weber. Berlioz praised the orchestra, when he appeared with it as Der Ring des Nibelungen conductor, and in the 1880s Stuttgart was one of the first to stage the complete Ring cycle, conducted by the then (The Ring of the Nibelung) General Music Director Herman Zumpe, who had assisted Wagner at the first Bayreuth Festival. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Das Mädchen Mit Den Schwefelhölzern

Information Presse Helmut Lachenmann (né e n 1935) Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern (La Petite Fille aux allumettes) « Mus ik mit Bildern » d’apr ès des tex tes de H ans Chris tian Andersen, Gudr un Ensslin et Leonar d de Vinci (Edition Br eitkopf & Här tel) Commande H amburgische Staatsoper – Création janvier 1997 Nouvelle production - Création en France Spectacle non surtitré @ Palais Garnier Direction musicale Lothar Zagrosek lundi 17 septembre 2001 - 19h30 Mise en scène et décors Peter Mussbach mardi 18 septembre 2001 - 19h30 Costumes Andrea Schmidt-Futterer jeudi 20 septembre 2001 - 19h30 Dramaturgie Klaus Zehelein et Hans Thomalla vendredi 21 septembre 2001 - 19h30 Réalisation sonore Andreas Breitscheid samedi 22 septembre 2001 - 19h30 Chef des chœurs Michael Alber Etudes musicales Matthias Hermann Sopranos Elisabeth Keusch Dates des représentations à Stuttgart Sarah Leonard 12, 13, 14, 20 et 21 octobre 2001 Récitante Salomé Kammer 22, 23 et 24 février 2002 Rôle muet Mélanie Fouché Orchestre et Chœurs du Staatstheater Stuttgart Tarifs : 577F, 460FF, 330FF, 200FF, 115FF, 60FF, 45FF 87,96€ 70,13€ 50,31€ 30,49€ 17,53€ 9,15€ 6,86 Coproduction Staatstheater Stuttgart Informations/Réservations Opéra National de Paris par téléphone 08 36 69 78 68 (2,23 FF/0,34€ la minute) et Festival d’Automne à Paris par Internet http://www.opera-de-paris.fr en Association avec la Fondation de France avec le concours de la Fondation Ernst von Siemens Durée : 2 heures sans entracte Attachée de presse : Pierrette Chastel 01 40 01 16 79 Attaché de presse Festival d’Automne à Paris : Rémi Fort Assistante : Diane Rayer 01 40 01 20 88 Assistante : Margherita Mantero Secrétariat : Françoise Domange 01 40 01 16 62 Tél. -

Annals Liceu

GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU I' Temporada d'òpera 1984/85 I f - CONSORCI DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU GENERALIl;�r DE CATALUNYA AJUNTAMENT DE BARCELONA SOCIETAT DEL GRAN TEATIlE DEL LICEU ,..------- (fi),�------------------� I SIEGFRIED Eso a menudo; la comida pasa Òpera en 3 actes es en cuanto a buena, pero Llibret i música de Richard Wagner postres, , , " sólo hay las tres banalidades de siempre, En Flo los postres son tantos que requieren una carta aparte: más de 20 postres hechos en casa, que son 20 suculentas tentaciones, Es que no puede haber una buena «brasserie» sin buenos postres, ¡QUE "BRASSERIE"! LA BRASSERIE FlO .. on LA LAI. Funció de Gala de a Dijous, 14 març de 1985 ' les 21 h ., funció núm. 37, torn B . 17 de 1985 a les 17 h ., Diumenge, març de ' funció núm. 38 , torn. T Dimecres, 20 de març de 1985 a les 21 h " funció núm. 39, torn A' Jonqueres, 10· BARCELONA Reservas Tel. 311 80 31 GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Barcelona --------(�--------� SIEGFRIED Siegfried: Reiner Goldberg Mime: Wolf Appel Wotan, el vianant: Peter W imberger Alberich: Walter Berry Fafner, el dragó: Malcolm Smith Erda: Martha Szirmay Brünnhilde: Elisabeth Payer-Tucci L'ocell: Rebeca Littig Director d'orquestra: Matthias Kuntzsch Direcció escènica: Werner M. Esser Decoracions: Teatro Comunale Giuseppe Verdi (Trieste) Violins concertinos: Jaume Franceschi a Josep M. Alpiste Comentaris a càrrec dels Drs. Roger Alier, Xosé Aviñoa i Oriol Martorell, del Departament d'Art de la Universitat de Barcelona. ORQUESTRA SIMFÒNICA DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU --------------------(!!)--------------------�