Neston High School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

170382 CVTSA Flyer V4

BECOME AN OUTSTANDING ASSOCIATE TEACHER Train to Teach with Cheshire Vale TSA We will be holding promotional events throughout the year: Tarporley High School 12th Oct 4 - 7pm Queen’s Park High School 19th Oct 4 - 7pm Please book a place by contacting Pam Bailey at [email protected] Applications to School Direct are made through UCAS For further information on how to apply for School Direct in our Alliance E-mail: [email protected] www.cvtsa.co.uk/become-teacher SCHOOL PLACES ON OFFER FOR 2016/17 Bishop Heber High School 3 www.bishopheber.cheshire.sch.uk Blacon High School 5 www.blaconhighschool.net The Catholic High School, Chester 1 www.chsc.cheshire.sch.uk Christleton High School 10 www.christletonhigh.co.uk Ellesmere Port Catholic High School 3 www.epchs.co.uk Hartford Church of England High School 11 www.hartfordhigh.org.uk Helsby High School 5 www.helsbyhigh.org.uk Neston High School 10 www.nestonhigh.cheshire.sch.uk Helsby Hillside Primary School 1 www.helsbyhillside.co.uk Manor House Primary School 1 www.manorhouse.cheshire.sch.uk Frodsham CE Primary School 1 www.frodshamce.cheshire.sch.uk Kingsley Community Primary and Nursery School 1 www.kingsleycp.cheshire.sch.uk Queen’s Park High School 7 www.qphs.cheshire.sch.uk St Nicholas Catholic High School 4 www.st-nicholas.cheshire.sch.uk Tarporley High School 9 www.tarporleyhigh.co.uk Upton-by-Chester High School 3 www.uptonhigh.co.uk Weaverham High School 5 www.weaverham.cheshire.sch.uk WE WILL OFFER PLACES IN THE FOLLOWING SUBJECTS FOR 2016/17 Maths Computer Science (ICT) Music English Drama Geography Biology Art & Design Business Chemistry MFL RE Physics D & T Primary PE History Fees for School Direct are £9,000. -

Martin Griffin and Jon Mayhew

Martin Griffin and Jon Mayhew Storycraft_250919.indd 1 04/10/2019 08:50 First published by Crown House Publishing Crown Buildings, Bancyfelin, Carmarthen, Wales, SA33 5ND, UK www.crownhouse.co.uk and Crown House Publishing Company LLC PO Box 2223, Williston, VT 05495, USA www.crownhousepublishing.com © Martin Griffin and Jon Mayhew, 2019 The rights of Martin Griffin and Jon Mayhew to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2019. Illustration p. 15 © Les Evans, 2019. Cover images © LiliGraphie, L.Dep – fotolia.com All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permis- sion of the copyright owners. Enquiries should be addressed to Crown House Publishing. Quotes from Ofsted and Department for Education documents used in this publication have been approved under an Open Government Licence. Please see: http://www.nationalarchives. gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/. British Library of Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library. LCCN 2019947469 Print ISBN 978-178583402-8 Mobi ISBN 978-178583463-9 ePub ISBN 978-178583464-6 ePDF ISBN 978-178583465-3 Printed in the UK by Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion Storycraft_250919.indd 2 04/10/2019 08:50 Preface We’ve managed to clock up over twenty years each in the classroom as English teachers at Key Stages 3, 4 and 5. -

Youth Arts Audit: West Cheshire and Chester: Including Districts of Chester, Ellesmere Port and Neston and Vale Royal 2008

YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER: INCLUDING DISTRICTS OF CHESTER, ELLESMERE PORT AND NESTON AND VALE ROYAL 2008 This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts supported by Arts Council England-North West and Cheshire County Council Angela Chappell; Strategic Development Officer (Arts & Young People) Chester Performs; 55-57 Watergate Row South, Chester, CH1 2LE Email: [email protected] Tel: 01244 409113 Fax: 01244 401697 Website: www.chesterperforms.com 1 YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER JANUARY-SUMMER 2008 CONTENTS PAGES 1 - 2. FOREWORD PAGES 3 – 4. WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER PAGES 3 - 18. CHESTER PAGES 19 – 33. ELLESMERE PORT & NESTON PAGES 34 – 55. VALE ROYAL INTRODUCTION 2 This document details Youth arts activity and organisations in West Cheshire and Chester is presented in this document on a district-by-district basis. This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts including; a separate document also for East Cheshire, a sub-regional and county wide audit in Cheshire as well as a report analysis recommendations for youth arts for the future. This also precedes the new structure of Cheshire’s two county unitary authorities following LGR into East and West Cheshire and Chester, which will come into being in April 2009 An audit of this kind will never be fully accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date. Some data will be out-of-date or incorrect as soon as it’s printed or written, and we apologise for any errors or omissions. The youth arts audit aims to produce a snapshot of the activity that takes place in West Cheshire provided by the many arts, culture and youth organisations based in the county in the spring and summer of 2008– we hope it is a fair and balanced picture, giving a reasonable impression of the scale and scope of youth arts activities, organisations and opportunities – but it is not entirely exhaustive and does not claim to be. -

Newsletter May 2017 Welcome to the Second Edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership Newsletter in 2017

Newsletter May 2017 Welcome to the second edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership newsletter in 2017. This newsletter focuses on the Level 3 School Games competitions which are the Cheshire and Warrington county finals for the Level 2 events held by Chester SSP over the last few months. A huge congratulations to all the schools who represented Chester, we had some amazing teams who took part in the competition which was spread out over a two week period in March across Cheshire. Overall we had eight schools from Chester who won medals, and one school won the Spirit of the Games award. This is a fantastic achievement and shows how strong Sport and PE is within our area. Thank you to all the teachers, parents, volunteers, and the children for your support at these fantastic events. The following pages show the results and a selection of photographs from each of the events. Page 1 Level 3 School Games: U15 Girls and Boys Handball Day 1 of the Cheshire and Warrington Winter School Games saw 10 schools from all over Cheshire and Warrington descend upon the Northgate Arena for the U15 Boys and Girls Handball competition. There was an excited buzz around the sports hall whilst all the teams warmed up. When all the schools had arrived the opening ceremony began, and the players sat in their schools teams with brightly coloured team shirts on show. Upton High School Girls and Tarporley High School Boys were our Chester schools representatives sporting the yellow t-shirts. The players made their way to the courts in readiness for the first games to begin, all players ready, the hooter sounded and the games began! The standard of handball just got better and better throughout the afternoon, high quality games were matched with excellent umpiring. -

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data As of 22 December 2020

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data as of 22 December Ad-hoc notice – laptops, tablets and 4G wireless routers for disadvantaged and vulnerable children: by academy trust and local authority December 2020 Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 Progress data for devices ............................................................................................. 4 Definitions .................................................................................................................... 5 Data Quality ................................................................................................................. 6 Annex A: Devices delivered by LA and Trust ............................................................... 7 Get laptops and tablets for children who cannot attend school due to coronavirus (COVID-19) and internet access for vulnerable and disadvantaged children Introduction For the 2020 to 2021 academic year, the Department for Education (DfE) is providing laptops and tablets to schools, academy trusts (trusts) and local authorities (LAs) to support children access remote education during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Laptops and tablets have been made available, if there is no existing access to a device, for: • disadvantaged children in years 3 to 11 whose face-to-face education is disrupted • disadvantaged children in any year group who have been advised to shield because they -

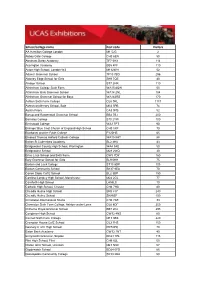

School/College Name Postcode Visitors

School/college name Postcode Visitors Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 45 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 100 Accrington & Rossendale College BB5 2AW 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 116 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 309 Alder Grange Community & Technology School BB4 8HW 99 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 126 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 60 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 170 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 160 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1223 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 56 Audenshaw School M34 5NB 55 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 54 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Baines School FY6 8BE 35 Barnsley College S70 2YW 153 Benton Park School LS19 6LX 125 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 105 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 95 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY2 0HB 94 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 80 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 55 Bradford College BD7 1AY 40 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 40 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 33 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 150 Burnley College BB12 0AN 500 Bury College BL9 0DB 534 Bury Grammar School Boys BL9 0HN 80 Buxton and Leek College SK17 6RY 100 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 90 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 69 Carnforth High School LA59LS 35 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 84 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 372 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 54 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 334 Congleton High School CW12 4NS -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors AA Hamilton College London M1 5JG 2 Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 50 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 110 Acton High School, London W3 M112WH 52 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 296 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 110 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 55 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 184 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 170 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1117 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 74 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 52 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Barnsley College S70 2YW 100 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 90 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 70 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY20HB 65 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 88 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 43 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 50 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 30 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 160 Bury Grammar School for Girls BL9 0HH 75 Buxton and Leek College ST13 6DP 103 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 70 Canon Slade Cof E School BL2 3BP 150 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 77 Carnforth High School LA59LS 10 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 80 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 240 Cheadle Hulme School SK86EF 150 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 33 Clarendon Sixth Form College, Ashton-under-Lyme OL6 6DF 250 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 295 Congleton High School CW12 4NS 60 Connell Sixth Form College M11 3BS 220 Crompton House -

INSPECTION REPORT NESTON HIGH SCHOOL Neston, Cheshire

INSPECTION REPORT NESTON HIGH SCHOOL Neston, Cheshire LEA Area: Cheshire Unique reference number: 111398 Headteacher: Mrs R Winterson Reporting inspector: David Young (OFSTED No: 2710) Dates of inspection: 12 – 16 March 2001 Inspection number: 187435 Full inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2001 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Comprehensive School category: Community Age range of students: 11 to 18 years Gender of students: Mixed School address: Raby Park Road Neston Cheshire Postcode: CH64 9NH Telephone number: 0151 336 3902 Fax number: 0151 353 0408 Appropriate authority: The Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Cllr R B Chrimes Date of previous inspection: 26 March 1996 Neston High School - 3 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Subject Aspect responsibilities Team members responsibilities 2710 David Young Registered What should the school do to inspector improve further? How high are standards? a) The school's results and achievements -

List of North West Schools

List of North West Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abraham Moss Community School Manchester 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Academy@Worden Lancashire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Accrington Academy Lancashire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Accrington and Rossendale College Lancashire Please check your secondary Please check your school. -

3846 Secondary School Guide 2018-19-Web

Important information for parents or carers Cheshire West & Chester Council Applying for a Secondary School place – Year 7 September 2018 Closing date for secondary school applications 31 October 2017 Visit: www.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/admissions 1 Timeline for Applying for a Secondary School Place for September 2018 1 September 2017 Parents/carers can apply for a school place. Online Paper www.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/ Application Form is contained in admissions Section 5 of this booklet. 31 October 2017 Closing date for on time applications • Paper applications to be returned to: School Admissions, Cheshire West and Chester Council, Wyvern House, The Drumber, Winsford, Cheshire, CW7 1AH. Paper applications must be received by this date to be considered as ‘on time’ • Online applications must be submitted to the Authority by this date. Don’t forget to press the submit button on your account. 1 March 2018 Notification of offers • Offer letters notifying parent/carers of school place offered sent out by post to parents/carers who have applied using a paper application. • Online offers made available for parents/carers to view, emails sent to parents/ carers who have applied online notifying of the school place offered. 9 March 2018 Parents/carers must accept or decline the school place offered. If accept/decline not received by this date the authority reserves the right to withdraw places. 29 March 2018 Closing date for on time appeals Appeals received by this date will be heard by 18 June 2018. Apply online visit: www.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/admissions 2 Apply online visit: www.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/admissions Dear Parents and Carers Welcome to the Cheshire West and Chester Council You may however prefer to complete a paper ‘Transferring to Secondary School 2018/19’ booklet. -

Revised Rates and Adjustments Certificate March 2021

Cheshire Pension Fund | Hymans Robertson LLP Rates and Adjustments Certificate In accordance with regulation 62(4) of the Regulations we have made an assessment of the contributions that should be paid into the Fund by participating employers for the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2023 in order to maintain the solvency of the Fund. The method and assumptions used to calculate the contributions set out in the Rates and Adjustments certificate are detailed in the Funding Strategy Statement dated 13 March 2020. and in Appendix 2 of our report on the actuarial valuation dated 30 March 2020. These assumptions underpin our estimate of the number of members who will become entitled to a payment of pensions under the provisions of the LGPS and the amount of liabilities arising in respect of such members. This is an updated version of the Rates and Adjustments certificate with updated rates for Burtonwood Community Primary School (employer code 225), Cheshire Community Action (12), David Lewis Centre (32) and Plus Dane (326). The table below summarises the whole fund Primary and Secondary Contribution rates for the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2023 (ignoring prepayments). The Primary rate is the payroll weighted average of the underlying individual employer primary rates and the Secondary rate is the total of the underlying individual employer secondary rates, calculated in accordance with the Regulations and CIPFA guidance. This Valuation 31 March 2019 Primary Rate (% of pay) 20.8% Secondary Rate (£) 2020/21 23,111,000 2021/22 18,759,000 2022/23 14,134,000 The required minimum contribution rates for each employer in the Fund are set out below.