Martin Griffin and Jon Mayhew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

170382 CVTSA Flyer V4

BECOME AN OUTSTANDING ASSOCIATE TEACHER Train to Teach with Cheshire Vale TSA We will be holding promotional events throughout the year: Tarporley High School 12th Oct 4 - 7pm Queen’s Park High School 19th Oct 4 - 7pm Please book a place by contacting Pam Bailey at [email protected] Applications to School Direct are made through UCAS For further information on how to apply for School Direct in our Alliance E-mail: [email protected] www.cvtsa.co.uk/become-teacher SCHOOL PLACES ON OFFER FOR 2016/17 Bishop Heber High School 3 www.bishopheber.cheshire.sch.uk Blacon High School 5 www.blaconhighschool.net The Catholic High School, Chester 1 www.chsc.cheshire.sch.uk Christleton High School 10 www.christletonhigh.co.uk Ellesmere Port Catholic High School 3 www.epchs.co.uk Hartford Church of England High School 11 www.hartfordhigh.org.uk Helsby High School 5 www.helsbyhigh.org.uk Neston High School 10 www.nestonhigh.cheshire.sch.uk Helsby Hillside Primary School 1 www.helsbyhillside.co.uk Manor House Primary School 1 www.manorhouse.cheshire.sch.uk Frodsham CE Primary School 1 www.frodshamce.cheshire.sch.uk Kingsley Community Primary and Nursery School 1 www.kingsleycp.cheshire.sch.uk Queen’s Park High School 7 www.qphs.cheshire.sch.uk St Nicholas Catholic High School 4 www.st-nicholas.cheshire.sch.uk Tarporley High School 9 www.tarporleyhigh.co.uk Upton-by-Chester High School 3 www.uptonhigh.co.uk Weaverham High School 5 www.weaverham.cheshire.sch.uk WE WILL OFFER PLACES IN THE FOLLOWING SUBJECTS FOR 2016/17 Maths Computer Science (ICT) Music English Drama Geography Biology Art & Design Business Chemistry MFL RE Physics D & T Primary PE History Fees for School Direct are £9,000. -

Youth Arts Audit: West Cheshire and Chester: Including Districts of Chester, Ellesmere Port and Neston and Vale Royal 2008

YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER: INCLUDING DISTRICTS OF CHESTER, ELLESMERE PORT AND NESTON AND VALE ROYAL 2008 This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts supported by Arts Council England-North West and Cheshire County Council Angela Chappell; Strategic Development Officer (Arts & Young People) Chester Performs; 55-57 Watergate Row South, Chester, CH1 2LE Email: [email protected] Tel: 01244 409113 Fax: 01244 401697 Website: www.chesterperforms.com 1 YOUTH ARTS AUDIT: WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER JANUARY-SUMMER 2008 CONTENTS PAGES 1 - 2. FOREWORD PAGES 3 – 4. WEST CHESHIRE AND CHESTER PAGES 3 - 18. CHESTER PAGES 19 – 33. ELLESMERE PORT & NESTON PAGES 34 – 55. VALE ROYAL INTRODUCTION 2 This document details Youth arts activity and organisations in West Cheshire and Chester is presented in this document on a district-by-district basis. This project is part of a wider pan Cheshire audit of youth arts including; a separate document also for East Cheshire, a sub-regional and county wide audit in Cheshire as well as a report analysis recommendations for youth arts for the future. This also precedes the new structure of Cheshire’s two county unitary authorities following LGR into East and West Cheshire and Chester, which will come into being in April 2009 An audit of this kind will never be fully accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date. Some data will be out-of-date or incorrect as soon as it’s printed or written, and we apologise for any errors or omissions. The youth arts audit aims to produce a snapshot of the activity that takes place in West Cheshire provided by the many arts, culture and youth organisations based in the county in the spring and summer of 2008– we hope it is a fair and balanced picture, giving a reasonable impression of the scale and scope of youth arts activities, organisations and opportunities – but it is not entirely exhaustive and does not claim to be. -

Neston High School

Neston High School Learning & Teaching Policy - 2 - Contents Page Neston High School – Learning & Teaching Policy.................................... - 4 - Supplementary Documentation.................................................................. - 7 - Section 1- Prompts for Teachers/Inspectors .............................................. - 8 - Section 2 - Teacher Behaviours - Exemplars............................................. - 9 - Section 3 - Assessment for Learning for the Classroom Teacher ........... - 14 - Section 4 - Behaviour for Learning for the Classroom Teacher................ - 29 - Section 5 - Data for the Classroom Teacher ........................................... - 34 - Section 6 - Getting the Most Out of More Able Students.......................... - 41 - Section 7 - Literacy across the Curriculum .............................................. - 53 - Section 8 - The Classroom Teacher’s Guide to Numeracy .......................... 67 Section 9 - What Every Classroom Teacher Should Know About SEN ....... 90 Section 10 – Dyslexia Friendly Approaches................................................. 99 Section 11 - Engagement Profile, Briefing Sheets & Inquiry Framework for Complex Needs ..........................................................................................105 Section 12 - Managing Marking and Feedback.......................................... 121 Section 13 - Teaching Vulnerable Students ............................................... 129 Section 14 - Creative Teaching Strategies................................................ -

Name Surname School Prize Jessica Green Tower College First Prize

Name Surname School Prize Jessica Green Tower College First Prize - The Ian Porteous Award Sam Ketchell Weaverham High School Second Prize with Special Commendation Bethan Rhoden Upton-by-Chester High School Second Prize with Special Commendation Benjamin Shearer Manchester Grammar School Second Prize with Special Commendation Isaac Corlett De La Salle Second Prize First 1 Beatrice De Goede Manchester High School for Girls Second Prize Second Prize with Special Commendation3 Lara Stone The King David High School, Liverpool Second Prize Second Prize 3 Quincy Barrett The King David High School, Manchester Third Prize Third Prize 17 Raka Chattopadhyay The Queen's School Third Prize Consolation Prize 20 Laura Craig The Bishops' Blue Coat High School Third Prize Certificate of Merit 86 Gemma Davies The Bishops' Blue Coat High School Third Prize Gemma Hemens Christleton High School Third Prize Total Prizes 44 Kelly Hong Wirral Grammar School for Girls Third Prize Total 130 Jessica Ingrey The King David High School, Liverpool Third Prize Olivia McCrave Wirral Grammar School for Girls Third Prize West Kirby Grammar School 10 Lauren Neil West Kirby Grammar School Third Prize Formby High School 7 Emily Page Christleton High School Third Prize The Queen's School 6 Rachel Pullin Wirral Grammar School for Girls Third Prize Ysgol Brynhyfryd 6 Isabel Roberts West Kirby Grammar School Third Prize Birkenhead School 5 Sam Roughley Merchant Taylors' School for Boys Third Prize Manchester Grammar School 5 Charlotte Russell Formby High School Third Prize Wirral -

Newsletter May 2017 Welcome to the Second Edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership Newsletter in 2017

Newsletter May 2017 Welcome to the second edition of the Chester School Sport Partnership newsletter in 2017. This newsletter focuses on the Level 3 School Games competitions which are the Cheshire and Warrington county finals for the Level 2 events held by Chester SSP over the last few months. A huge congratulations to all the schools who represented Chester, we had some amazing teams who took part in the competition which was spread out over a two week period in March across Cheshire. Overall we had eight schools from Chester who won medals, and one school won the Spirit of the Games award. This is a fantastic achievement and shows how strong Sport and PE is within our area. Thank you to all the teachers, parents, volunteers, and the children for your support at these fantastic events. The following pages show the results and a selection of photographs from each of the events. Page 1 Level 3 School Games: U15 Girls and Boys Handball Day 1 of the Cheshire and Warrington Winter School Games saw 10 schools from all over Cheshire and Warrington descend upon the Northgate Arena for the U15 Boys and Girls Handball competition. There was an excited buzz around the sports hall whilst all the teams warmed up. When all the schools had arrived the opening ceremony began, and the players sat in their schools teams with brightly coloured team shirts on show. Upton High School Girls and Tarporley High School Boys were our Chester schools representatives sporting the yellow t-shirts. The players made their way to the courts in readiness for the first games to begin, all players ready, the hooter sounded and the games began! The standard of handball just got better and better throughout the afternoon, high quality games were matched with excellent umpiring. -

Insert Title Text Here

Post 16 Education Travel Policy Statement Cheshire East Council 1 September 2018 www.cheshireeast.gov.uk OFFICIAL Document summary This document provides travel information for young people of sixth form age1 and adults aged 19 and over (including those with an Education, Health and Care (EHC) plan) in education and training2. Contents Section Title Page 1. Summary and Objectives 3 2. Post 16 Transport Duty 4 3. Details of Travel Assistance and Eligibility 5 4. Reviewing Eligibility 10 5. General Details 10 6. General Information on Travel Support 11 7. Support for Students reaching 19 14 8. Mobility/Independence Training 14 9. When to Apply for Support 15 10. Help Outside the Local Authority 15 11. Help for Establishments Outside Daily Travelling 15 12. ComplaintsDistance 16 Appendix 1 List of post 16 education providers in the area 17 Other related education travel policies: • Compulsory School Age Education Travel Policy • Education Travel Payments Policy • Education Travel Behaviour Code • Education Travel Appeals and Complaints Policy • Sustainable Modes of Travel Strategy 1 Section 508H and Section 509AB(5). 2 Section 509AC(1) of the Education Act 1996 defines persons of sixth form age for the purposes of the sixth form transport duty. OFFICIAL 2 1. Summary of Policy Statement and Objective 1.1 This policy statement provides information for Cheshire East students and their parents3 about the travel assistance available to them when continuing in education or training beyond compulsory school age4. It relates to Post 16 learners who are aged 16-18 years of age including those with special educational needs and disabilities aged 19 years of age including those with special educational needs and disabilities who started a course before their 19th birthday and who continue to attend that course Adults under 25 years of age, including those with special educational needs and disabilities, with or without an Education and Health Care Plan (EHCP) who wish to attend an educational course. -

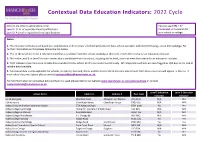

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data As of 22 December 2020

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data as of 22 December Ad-hoc notice – laptops, tablets and 4G wireless routers for disadvantaged and vulnerable children: by academy trust and local authority December 2020 Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 Progress data for devices ............................................................................................. 4 Definitions .................................................................................................................... 5 Data Quality ................................................................................................................. 6 Annex A: Devices delivered by LA and Trust ............................................................... 7 Get laptops and tablets for children who cannot attend school due to coronavirus (COVID-19) and internet access for vulnerable and disadvantaged children Introduction For the 2020 to 2021 academic year, the Department for Education (DfE) is providing laptops and tablets to schools, academy trusts (trusts) and local authorities (LAs) to support children access remote education during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Laptops and tablets have been made available, if there is no existing access to a device, for: • disadvantaged children in years 3 to 11 whose face-to-face education is disrupted • disadvantaged children in any year group who have been advised to shield because they -

Microsoft Schools List November 2019

Microsoft Schools List November 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Caba Educacion IT Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex اﻟ��ﺎض Aruba Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Adelaide St Mary's College Australia Ascot St. Margaret's Anglican Girls School Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ballarat Mount Pleasant Primary School Australia Ballarat St. Patrick's College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Bentleigh Bentleigh West Primary School Australia Bentley Park Bentley Park College Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Brisbane Holy Family School Australia Brisbane Kedron State High School Australia Brisbane Stuartholme School Microsoft Schools List November 2019 Australia Cairns Peace Lutheran Collage Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Carrum Downs Rowellyn Park Primary School Australia Cranbourne Cranbourne Carlisle Primary Australia East Ipswich Ipswich Girls Grammar incorporating Ipswich Junior Grammar Australia Ellenbrook St. -

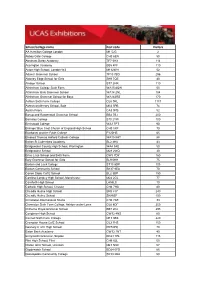

School/College Name Postcode Visitors

School/college name Postcode Visitors Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 45 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 100 Accrington & Rossendale College BB5 2AW 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 116 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 309 Alder Grange Community & Technology School BB4 8HW 99 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 126 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 60 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 170 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 160 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1223 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 56 Audenshaw School M34 5NB 55 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 54 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Baines School FY6 8BE 35 Barnsley College S70 2YW 153 Benton Park School LS19 6LX 125 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 105 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 95 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY2 0HB 94 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 80 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 55 Bradford College BD7 1AY 40 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 40 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 33 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 150 Burnley College BB12 0AN 500 Bury College BL9 0DB 534 Bury Grammar School Boys BL9 0HN 80 Buxton and Leek College SK17 6RY 100 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 90 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 69 Carnforth High School LA59LS 35 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 84 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 372 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 54 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 334 Congleton High School CW12 4NS -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

School/College Name Post Code Visitors

School/college name Post code Visitors AA Hamilton College London M1 5JG 2 Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN 50 Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX 114 Accrington Academy BB5 4FF 110 Acton High School, London W3 M112WH 52 Adams' Grammar School TF10 7BD 296 Alderley Edge School for Girls SK9 7QE 40 Alsager School ST7 2HR 110 Altrincham College Sixth Form WA15 8QW 55 Altrincham Girls Grammar School WA14 2NL 184 Altrincham Grammar School for Boys WA142RS 170 Ashton Sixth Form College OL6 9RL 1117 Ashton-on-Mersey School, Sale M33 5PB 74 Austin Friars CA3 9PB 52 Bacup and Rawtenstall Grammar School BB4 7BJ 200 Barnsley College S70 2YW 100 Birchwood College WA3 7PT 90 Bishops' Blue Coat Church of England High School CH3 5XF 70 Blackpool and the Fylde College FY20HB 65 Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College WA15 8HT 88 Bolton St Catherines Academy BL2 4HU 43 Bridgewater County High School, Warrington WA4 3AE 50 Bridgewater School M28 2WQ 30 Brine Leas School and Sixth Form CW5 7DY 160 Bury Grammar School for Girls BL9 0HH 75 Buxton and Leek College ST13 6DP 103 Buxton Community School SK17 9EA 70 Canon Slade Cof E School BL2 3BP 150 Cardinal Langley High School, Manchester M24 2GL 77 Carnforth High School LA59LS 10 Catholic High School, Chester CH4 7HS 80 Cheadle Hulme High School SK8 7JY 240 Cheadle Hulme School SK86EF 150 Christleton International Studio CH4 7AE 33 Clarendon Sixth Form College, Ashton-under-Lyme OL6 6DF 250 Clitheroe Royal Grammar School BB7 2DJ 295 Congleton High School CW12 4NS 60 Connell Sixth Form College M11 3BS 220 Crompton House