The Disinterment of Pet Sematary Two Douglas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Az Archetipikus Csövigyerek-Banda: Ramones

Koko Kommandó Az archetipikus csövigyerek-banda: Ramones Többé-kevésbé mindenkinek megvan az egy vagy több életre szóló esete. Az én LEG-eim között a legeslegesebb a RAMONES. Amikor 1976 végén az Újvidéki Rádióba megérkeztek az első punk lemezek (Sex Pistols, Patti Smith Group, The Clash, Dr. Feelgood, The Stranglers, Ramones), mindjárt lecsaptam rájuk - megéreztem, tudtam, hogy ez az, ami nekem kell, ez az én zeném. A Judy Is A Punk szédületes tempója egyből kiakasztott. Igen, „szerelem első pillantásra" volt, vagy operettmagyarul: szerelem első vérig. A Ramones számaival való találkozás alapélmény volt. Reménytelen, boldog szerelem, hiszen csak metafizikai viszonzásról beszélhettünk. Ez a zene soha nem hagyott cserben, soha nem volt hozzám hűtlen, soha nem okozott fájdalmat. A legnehezebb pillanatokon segített, lendített át. Szilárd pont az életemben. A nők jöttek-mentek, s mára az otthonomból és a munkahelyemről is elüldöztek. Azon az 1991-es novemberi napon, amikor még katonai engedély nélkül távozhattam a szerb birodalomból, a Ramones-kazetták ott lapultak a poggyászomban. Egy ilyen elfogult vallomás után illene valamit mondani a zenekarról, s nem utolsósorban a zenéről, amit játszanak _ hisz errefelé nem sok szó esett róluk. A legjelentősebb magyar rock- kritikusok ugyan számon tartják őket, de a tömérdek lapban s a rádiókban szinte semmit sem találni róluk. Egyszóval: siralmas állapot. Mintha depressziós lenne ez az ország zeneileg. We're A Happy Family A Ramones 1974-ben alakult. Kezdetben három queens-i fiú, John Cummings, Douglas Colman és Jeffry Hyman alkotta. Johnny és Dee Dee gitáron játszott, míg Joey dobolt. Thomas Erdélyi menedzserként szorgoskodott, de aztán átvette a dobokat Joey-tól, aki előrement énekesnek. -

Roxbox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat

RoxBox by Artist (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Play Feat. Thomas Jules & Bartender Jucxi D Blackout Careless Whisper Other Side 2 Unlimited 10 Years No Limit Actions & Motives 20 Fingers Beautiful Short Dick Man Drug Of Choice 21 Demands Fix Me Give Me A Minute Fix Me (Acoustic) 2Pac Shoot It Out Changes Through The Iris Dear Mama Wasteland How Do You Want It 10,000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Because The Night 2Pac Feat Dr. Dre Candy Everybody Wants California Love Like The Weather 2Pac Feat. Dr Dre More Than This California Love These Are The Days 2Pac Feat. Elton John Trouble Me Ghetto Gospel 101 Dalmations 2Pac Feat. Eminem Cruella De Vil One Day At A Time 10cc 2Pac Feat. Notorious B.I.G. Dreadlock Holiday Runnin' Good Morning Judge 3 Doors Down I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun The Things We Do For Love Be Like That Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 112 Citizen Soldier Dance With Me Duck & Run Peaches & Cream Every Time You Go Right Here For You Here By Me U Already Know Here Without You 112 Feat. Ludacris It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Hot & Wet Kryptonite 112 Feat. Super Cat Landing In London Na Na Na Let Me Be Myself 12 Gauge Let Me Go Dunkie Butt Live For Today 12 Stones Loser Arms Of A Stranger Road I'm On Far Away When I'm Gone Shadows When You're Young We Are One 3 Of A Kind 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Bahs May 2009.Indd

Berlin Brats Alumni Association Newsletter April 2009 Volume 6, Issue 2 Berlin Topples Wall all Over Again to Celebrate Anniversary Berlin officials are counting on the domino effect as the city celebrates the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall this November. Over 1,000 2Oth ANNIVERSARY eight foot tall Styrofoam tiles will be stacked along a 1.2-mile section of the former border between Potsdamer Platz and the iconic Brandenburg Gate and of the FALL of the toppled during celebrations on November 9, 2009. While the Berlin Wall stood for 28 years before it came down on November 9, 1989, the dominoes will be BERLIN WALL set up on November 7th and collapse in about a half hour during the November 9th “Freedom Fest” celebrating the fall of the Wall. www.mauerfall09.de (***Attendees of “Homecoming 2001” may remember we, the Berlin Brats, did a similar project to compete against other Michael Mieth paints a domino tile in Berlin DoDDs school for the “School Spirit Award.” Under the (© picture-alliance/dpa) creative eye of Cate Speer ‘85, we built the Berlin Wall out of uniformed cardboard boxes. One side of the wall had The dominoes are to be decorated by students and young artists in “Berlin” stamped on each brick (each box) with the other side Berlin and around the world with motives relating to the fall of the of the wall appearing blank. As Homecoming attendees entered Berlin Wall. Students can apply to participate by submitting an the Exhibit Hall.....they were handed a sharpie and asked to application including a sketch on the project’s Website. -

Firefly Books Escape from Syria Samya

FIREFLY BOOKS Firefly Books Escape from Syria Summary: "Groundbreaking and unforgettable." Samya Kullab, Jackie Roche --Kirkus (starred review) Pub Date: 9/1/20 $9.95 USD "This is a powerful, eye-opening graphic novel that will 96 pages foster empathy and understanding in readers of all ages." --The Globe and Mail "In league with Art Spiegelman's Maus and Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis, this is a must-purchase for any teen or adult graphic novel collection." --School Library Journal (starred review) From the pen of former Daily Star (Lebanon) reporter Samya Kullab comes this breathtaking and hard-hitting story IDW Publishing Life in the Stupidverse Summary: Welcome to the Stupidverse! Good luck Tom Tomorrow finding an exit. Pub Date: 9/1/20 $19.99 USD Relive all the trauma of the first several years of the Trump 128 pages presidency through the Pulitzer-nominated cartoons of Tom Tomorrow! You’ve never laughed quietly to yourself so much at humanity’s impending doom! It’s a hilarious but nightmarish trip down memory lane, from the Great Inaugural Crowd Size debate to the nomination of Bret (“I LIKE BEER”) Kavanaugh, from Muslim bans to concentration camps, from the Mueller report to the latest outrageous thing you just read about this morning—Tom Talos The Girl with No Face : The Daoshi Summary: *Winner--First Prize in the Colorado Chronicles, Book Two Authors League Award, Science Fiction and Fantasy M. H. Boroson Category!* Pub Date: 9/1/20 $7.99 USD The adventures of Li-lin, a Daoist priestess with the 480 pages unique ability to see the spirit world, continue in the thrilling follow-up to the critically-acclaimed historical urban fantasy The Girl with Ghost Eyes. -

Entertainment Memorabilia

Entertainment Memorabilia Including a collection from BAFTA Montpelier Street, London I 13 October 2020 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams European Board Registered No. 4326560 Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Simon Cottle Chairman, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Matthew Girling, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Matthew Girling CEO, Jonathan Fairhurst, Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Harvey Cammell, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Asaph Hyman, Caroline Oliphant, Philip Kantor, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Edward Wilkinson, Geoffrey Davies, James Knight, Victoria Rey de Rudder, Jon Baddeley, Jonathan Fairhurst, Leslie Wright, Catherine Yaïche, Rupert Banner, Shahin Virani, Simon Cottle. Emma Dalla Libera Entertainment Memorabilia Including a collection from Montpelier Street, London | Tuesday 13 October 2020 at 1pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER: REGISTRATION Montpelier Street Claire Tole-Moir 25996 IMPORTANT NOTICE Knightsbridge, +44 (0) 20 7393 3984 Please note that all customers, London SW7 1HH [email protected] CATALOGUE: irrespective of any previous activity www.bonhams.com £15 with Bonhams, are required to Katherine Schofield complete the Bidder Registration +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 Form in advance of the sale. The VIEWING PRESS ENQUIRIES [email protected] form can be found at the back of Saturday 10 October [email protected] every catalogue and on our website 10am to 3pm Stephen Maycock at www.bonhams.com and should Sunday 11 October +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 CUSTOMER SERVICES -

The Daily Egyptian, June 14, 2002

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 2002 Daily Egyptian 2002 6-14-2002 The Daily Egyptian, June 14, 2002 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June2002 Volume 87, Issue 154 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 2002 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 2002 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~{.. .. :Pri•~~f.tff~1W,l•~~.f1r~~~T{I ., ~ . " . , . -· . .. ~ ... ' .. , ..: ..... '. .. .. .. .... "' .... ,. ; New Osbourne famlh,1 CD.hit store sh~lves this·" week. Oieck out our . - take ori the new album : .. ·o~ pc:ige.11 · fiTiiER o:iiDARKNEss. ·. Vol87iNO, 1s4:}~ ~ Ttie:WaxcJoHs. fclCe the musk, A legendary." locaJ T:c:~~ughtthcm ~er, but in ~e-~d itsp=d ' ' / · · k - ·-· · - · · The Waxaolls had a tumultuous carc.irin the local music : l ,sccne,spanningafi.ve-)~period;FoundingincmbcrsShmm a ternatzve ,roe. -ac.~ 4PP.~9-.~,, ;. 1 , h- · ·· -.{ . · fi- - l ' ·h ,l ! - l i! : · ;Dawson an? JC?n E. Rectoi; were into slightly different styles toget er 10r-011.e . TI4 }S_ QW• · - ofrt1usic.Rectors~ou~h~\ilyiiJ!lu~ccdby,CJu½tian · - · - · · rock, and Dawson was mspucd by alt~~ rock. One thing the duo co_uld agree 'on was the music ofthe;. , Replacements, an al_tcrnative pop band. Th_ey eventually . STORY BY JARED DUBACH I • formed their own group with a sunilir sound. But as they aged and mar.ired; their tastes ill music drifte-l _apart,_as d,id their interest in the band. · ·, : But before they separate for good; the Waxdol!s \\ill perfomi one last time tonight at Booby's Beer Garden; , The group's roots go back to when lead . -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack -

Die Domestizierung Des Ingolf Lück

Dienstag, 28. September 2010 SZENE LEIPZIG Seite 11 SZENE-TIPPS Theater der Jungen Welt Zielgenau: Die Hamburger Indie-Band Wilhelm Tell Me gibt im Studio des Online- Werkstatt-Tage Senders Detektor.fm (Erich-Zeigner-Allee 69-73) heute um 21 Uhr ein Radio-Konzert, Eintritt frei. mit Hindernissen Auf den Punkt: Die Leipziger Gruppe Zap- Wie sich das anfühlt, oder besser: nicht fen tritt heute um 20 Uhr in der Anker-Knei- anfühlt, wenn das von oben durchge- pe (Renftstraße 1) auf, Eintritt frei. reichte Spardiktat unten ankommt, hat Treffsicher: Kabarettistin Katrin Weber das Theater der Jungen Welt vor dem teilt sich die Bühne der Academixer (Kup- heutigen Beginn der 17. Werkstatt-Tage fergasse 2) heute um 20 Uhr nur mit ihrem peinlich erlebt. Von den sieben Inszenie- Pianisten Rainer Vothel, also heißt ihr Pro- rungen, die Intendant Jürgen Zielinski gramm „Solo“, Eintritt 14 bis 20 Euro. als künstlerischer Leiter des Festivals und seine Kollegen im Mai ausgewählt Kurz und knapp: Im Rahmen der Latein- hatten, mussten sie zwei Ensembles amerikanischen Tage sind heute um 20.30 wieder ausladen. 80 000 Euro fehlen im Uhr im Raum der Kulturen (Engertstraße Budget gegenüber den ursprünglichen 23) Kurzfilme des Kontinents zu sehen. Planungen, also trifft sich die deutsche Hurtig: Bevor in der Schaubühne Linden- Sektion des Weltverbands der Kinder- fels (Karl-Heine-Straße 50) heute um 20 und Jugendtheater zwar zum dritten Uhr der türkische Spielfilm „Süt“ läuft, gibt Mal in Folge in Leipzig, jedoch ohne das der Kinotechniker ab 18 Uhr in einer Stipp- Junge Schauspiel Hannover und ohne visite Einblicke in die Filmvorführung. -

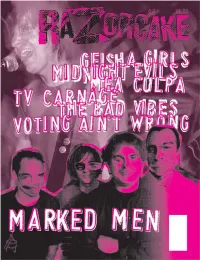

Razorcake Issue

was at a state university in southern California, talking four-foot-tall shower, all so he could afford to help open to a literature professor. Since I didn’t want to be up the zine store/art space Needles and Pens; and to hear IIbogged down in small talk, I figured I could talk about Joe say again and again how these little reading tours were books with her. I asked her, “What’s the last thing you our way of recreating the old ‘80s punk rock tours by read that got you really excited?” getting in the van and bringing underground books to “Oh, I don’t read for pleasure,” she said. “When I get people who have an appetite for them. home, I just watch TV.” The icing on the cake came in Seattle, when Joe and I Because I’m a writer, this comment really stung. If were hanging out in front of Confounded Books and this even literature professors don’t read, then who does? guy came up to us and said, “I’m so excited you guys are Books and zines mean the world to me, and for a minute, I here. This is like my Wrestlemania!” Any bad feelings I wondered if I was the only person left who felt this way. may have had or any remnants of the mundane tour week earlier, I’d been on a reading tour with three malaise were wiped away with that one little comment. of my favorite living writers: Mike Faloon, Joe For the rest of the tour, whenever people would ask us AAMeno, and Razorcake’s own Todd Taylor. -

Buntgemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB

Seite 1 von 284 -BuntGemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 A winziger Funken 3:05 Jeder Tag Zählt - STS - 1990 (IT-320) S.T.S. 2 A year 5:47 Piledriver - Status Quo - 1972 (LP) Status Quo 3 Ab + Zua 3:55 Ûber'n Berg - Die Seer - 2004 (IT-320) Die Seer 4 Abadabadango 3:54 Barking At Airplanes Carnes Kim 5 ABC 2:58 ABC - Jackson Five - 1970 (RS-128) Jackson Five 6 Abenteuer Leben 4:12 1 Tag - Die Seer - 2007 (IT-256) Die Seer 7 Abenteuerland (Single Version) 4:43 Bravo Hits 1995 - Comp 1995 (CD2-VBR) PUR 8 Aber bitte mit Sahne 3:38 Aber bitte mit Sahne I - Udo Jürgens - Comp 2004 (RS-192) Jürgens Udo 9 Aber niemals 4:24 Jeder Tag Zählt - STS - 1990 (IT-320) S.T.S. 10 Aber was soll's 3:55 Keine Angst - Georg Danzer - 1991 (IT-256) Danzer Georg 11 Abide with me 4:49 Rock Of Ages... Hymns & Faith - Amy Grant - 2005 (VA-320) Grant Amy 12 Abilene (ft Natalie Maines - Background) 4:08 C'mon, C'mon - Sheryl Crow - 2002 (RS-192) Crow Sheryl 13 Abracadabra 5:05 Abracadabra Miller Band, Steve 14 Abriendome Paso 4:10 Sister Bossa 10 - Comp 2011 (RS) Caradefuego 15 Abschied 4:07 Meine Zeit - Rainhard Fendrich - 2010 (RS) Fendrich Rainhard 16 Absence of fear / This little bird 7:26 Spirit - Jewel - 1998 (RS-256) Jewel (Kilcher) 17 Absence of the heart 3:31 Everything's Gonna Be Alright - Deana Carter - 1998 (RS) Carter Deana 18 Absolutely everybody 3:44 Bravo Hits 31 - Comp 2000 (CD1-VBR) Amorosi Vanessa 19 Acapulco 2:50 The Jazz Singer - Neil Diamond - 1980 (RS) Diamond Neil 20 Ace of hearts 4:29 Wired To The Moon - Chris -

PUNK by Jon Savage I

PUNK By Jon Savage I: INTRO I’m a street-walking cheetah with a heartfull of napalm… It starts with a feeling. I’m the runaway son of the nuclear A-bomb…. A feeling so intense and so out there that it struggles to make itself heard. I am the world’s forgotten boy… These screams of rage fall on deaf ears in the woozy hedonism of the early seventies. The singer is: too dumb, too blank, too violent. A dose of Amphetamine among the Quaaludes. He cuts himself on stage, flings himself into the audience…. Sick boy, sick boy, learning to be cruel… ..trying to get a reaction, any reaction. Anything but this boredom. Anything but this stoner ooze that avoids the issue of what it is to be young, outcast, and ready to murder a world. Is there concrete all around or is it in my head? The bloom is off youth culture as the promises of the sixties fade. The charismatic dark stars of the early seventies, David Bowie, Alice Cooper, catch this mood but by mid decade they are too successful and too old - sixties people themselves – to embody this feeling. They can write as observers but they aren’t inside it. I’m getting tired of being alone…. The secret heart of pop culture shifts from the country to the inner city. This is a dark, dangerous world. It’s a jungle out there. WWW.TEACHROCK.ORG Somethin’ comin’ at me all the time…. But after sundown, when everyone has fled, there is space. The new breed find the feeling in the midst of emptiness. -

Students Held at Knife Point Two Intruders Threaten and Rob Foxcroft·Apartment Residents

], Sports In Sectio" 2 Men•s soccer An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper tamed by Wild Balls roll !igers on to scene page 85 page 81 Students held at knife point Two intruders threaten and rob Foxcroft·apartment residents By Kenny Nager drawers and got out another knife, he City News tdilor said. Two off-campus students were Police said the second male went robbed at knife point in their upstairs with a knife to where Foxcroft townhouse Wednesday Clayton was sleeping and demanded afternoon, Newark Police said. money from him. Mike Qayton (AG JR) and Doug "This guy came in and told me to Einstein, a student currently enrolled lie face down on the bed while he in the university's parallel program went through my drawers and tossed in Wilmington, said they now know things around the room," Clayton how it feels to be totally helpless. said. "He was yelling for me to give "It was probably the only time I him all of my money." . felt useless and there was nothing I Einstein sai4 he was brought could do about it," Clayton said. upstairs and at times had a knife "We're both a little shaken up, but pinned to his neck. The suspect then we're OK." threatened Clayton to tell him where Police said two men forced their his money was or he would cut his way through the front door at about roommate. 1:30 p.m. and placed a long serrated "It was scary," Einstein said. "I knife to Einstein's neck.