PUNK by Jon Savage I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

The Sur-Metre

The Sur-Metre "D1mn" has geared wmches operated From under the deck, the wmches alongs1de the mam cockpit having large drums for Geno4 sheet Md spinnaker ge4r Note the Geno4 sheet lead blocks on the r4il, the boom downhaulcJnd the rod riggmg Just o~fter a sto~rt of tbe Sixes. No. 72 is Stanley Barrows' Strider, No. 38 is George So~t~cbn's /ll o~ybe, 50 is Ripples, · sailed by Sally Swigart. 46 Vemotl Edler's Capriu, o~ml 77 is St. Fro~tlciS , sailed by VincetJt Jervis. Lmai was out aheatl o~Jld to windward.- Photo by Kent Hitchcock. MEN and BOATS Midwinter Regatta at Los Angeles Again Deanonstrates That it is not Enough to Have a Fast Boat; for Boat, Skippe r and Crew Must All he Good to Form n Winning Combination AS IT the periect weather. or the outside competition, the time-tested maxim that going up the beach is best. Evidently W or the lack of acrimonious protest hearings, or the he did it on the off chance of gaining by splitting with Prel11de, smooth-running race committees, or the fact that it was the first which was leading him by some six minutes. Angelita mean regatta of the year, or all four rea~ ons that made this Midwinter while was ardently fo ll owing the maxim and to such good seem to top all others? advantage that when the two went about and converged llngl!l Anyway, there had been a great deal of advance speculation. it,/J starboard tack put her ahead as Yucca passed an elephant's How would the men from San francisco Bay do with their new e)•ebrow astern. -

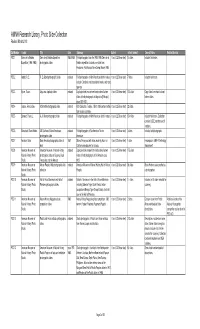

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept

® The GRAMMY Museum and Delta Air Lines Present Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Opening Friday, Sept. 16 Linda Ramone, Billy Idol, Seymour Stein, Shepard Fairey, And Monte A. Melnick To Appear At The Museum Opening Night For Special Evening Program LOS ANGELES (Aug. 24, 2016) — Following its debut at the Queens Museum in New York, on Sept. 16, 2016, the GRAMMY Museum® at L.A. LIVE and Delta Air Lines will present the second of the two-part traveling exhibit, Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk. On the evening of the launch, Linda Ramone; British pop/punk icon Billy Idol; Seymour Stein, Vice President of Warner Bros. Records and a co-founder of Sire Records, the label that signed the Ramones to their first record deal; artist Shepard Fairey; and Monte A. Melnick, longtime tour manager for the Ramones, will participate in an intimate program in the Clive Davis Theater at 7:30 p.m. titled "Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Celebrating 40 Years Of The Ramones." Tickets can be purchased at AXS.com beginning Thursday, Aug. 25 at 10:30 a.m. Co-curated by the GRAMMY Museum and the Queens Museum, in collaboration with Ramones Productions Inc., the exhibit commemorates the 40th anniversary of the release of the Ramones' 1976 self-titled debut album and contextualizes the band in the larger pantheon of music history and pop culture. On display through February 2017, the exhibit is organized under a sequence of themes — places, events, songs, and artists —and includes items by figures such as: Arturo Vega (who, along with the Ramones, -

Scenes and Subcultures

ISSN 1751-8229 IJŽS Volume Three, Number One Realizing the Scene; Punk and Meaning’s Demise R. Pope - Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada. Joplin and Hendrix set the intensive norm for rock shows, fed the rock audience’s need for the emotional charge that confirmed they’d been at a “real” event… The ramifications were immediate. Singer-songwriters’ confessional mode, the appeal of their supposed “transparency”, introduced a kind of moralism into rock – faking an emotion (which in postpunk ideology is the whole point and joy of pop performance) became an aesthetic crime; musicians were judged for their openness, their honesty, their sensitivity, were judged, that is, as real, knowable people (think of that pompous rock fixture, the Rolling Stone interview)’. -Simon Frith, from `Rock and the Politics of Memory’ (1984: 66-7) `I’m an icon breaker, therefore that makes me unbearable. They want you to become godlike, and if you won’t, you’re a problem. They want you to carry their ideological load for them. That’s nonsense. I always hoped I made it completely clear that I was as deeply confused as the next person. That’s why I’m doing this. In fact, more so. I wouldn’t be up there on stage night after night unless I was deeply confused, too’. -John Lydon, from Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1994: 107) `Gotta go over the Berlin Wall I don't understand it.... I gotta go over the wall I don't understand this bit at all... Please don't be waiting for me’ -Sex Pistols lyrics to `Holidays in the Sun’ INTRODUCTION: CULTURAL STUDIES What is Lydon on about? What is punk 'about’? Within the academy, punk is generally understood through the lens of cultural studies, through which punk’s activities are cast an aura of meaningful `resistance’ to `dominant’ forces. -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 1 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhatt

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village, CBGB was a bar and music venue which features prominently in the history of American punk rock, New Wave and Hardcore music genres. The club’s owner, Hilly Kristal, was always involved with music and musicians, having worked as a manager at the legendary jazz club Village Vanguard booking acts like Miles Davis. When CBGB first opened its doors in the early seventies the venue featured mostly country, blue grass, and blues acts (thus CBGB) before transitioning over to punk rock acts later in the decade. Many well know performers of the punk rock era received their start and earliest exposure at the club, including the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, and Joan Jett. During the New Wave era, performers like Elvis Costello, Talking Heads and even early performances from the Police graced the stage in the now legendary venue. Located at 315 Bowery, which is situated near the northern section of Bowery before it splits into 3rd and 4th Avenues at Cooper square, the original building on the site was constructed in 1878 and was used as a tenement house for 10 families with a shop (liquor store) on the ground floor. In 1934, 315 and 313 were combined into one building and the façade was redesigned and constructed in the Art Deco style, as documented in the 1940 tax photo. At that time, the building was occupied by the Palace Hotel with a ground floor saloon. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

PUNK/ASKĒSIS by Robert Kenneth Richardson a Dissertation

PUNK/ASKĒSIS By Robert Kenneth Richardson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program in American Studies MAY 2014 © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by Robert Richardson, 2014 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of Robert Richardson find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Thomas Vernon Reed, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Kristin Arola, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Laws are like sausages,” Otto von Bismarck once famously said. “It is better not to see them being made.” To laws and sausages, I would add the dissertation. But, they do get made. I am grateful for the support and guidance I have received during this process from Carol Siegel, my chair and friend, who continues to inspire me with her deep sense of humanity, her astute insights into a broad range of academic theory and her relentless commitment through her life and work to making what can only be described as a profoundly positive contribution to the nurturing and nourishing of young talent. I would also like to thank T.V. Reed who, as the Director of American Studies, was instrumental in my ending up in this program in the first place and Kristin Arola who, without hesitation or reservation, kindly agreed to sign on to the committee at T.V.’s request, and who very quickly put me on to a piece of theory that would became one of the analytical cornerstones of this work and my thinking about it.