COMED Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: the Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-2, Issue-2, Mar-Apr- 2017 ISSN: 2456-7620 “Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: The Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C. Department of Theatre and Media Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Abstract— The private and the opposition-controlled environment where totalitarianism, dictatorship and other media have most often been taxed by Black African forms of unjust socio-political strictures reign. They are governments with being adepts of adversarial journalism. not to be intimidated or cowed by any aggressive force, to This accusation has been predicated on the observation kill stories of political actions which are inimical to public that the private media have, these last decades, tended to interest. They are rather expected to sensitize and educate dogmatically interpret their watchdog role as being an masses on sensitive socio-political issues thereby igniting enemy of government. Their adversarial inclination has the public and making it sufficiently equipped to make made them to “intuitively” suspect government and to solid developmental decisions. They are equally to play view government policies as schemes that are hardly – the role of an activist and strongly campaign for reforms nay never – designed in good faith. Based on empirical that will bring about positive socio-political revolutions in understandings, observations and secondary sources, this the society. Still as watchdogs and sentinels, the media paper argues that the same accusation may be made are expected to practice journalism in a mode that will against most Black African governments which have promote positive values and defend the interest of the overly converted the state-owned media to their public totality of social denominations co-existing in the country relation tools and as well as an arsenal to lambaste their in which they operate. -

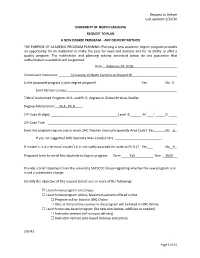

Request to Deliver Last Updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY of NORTH

Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA REQUEST TO PLAN A NEW DEGREE PROGRAM – ANY DELIVERY METHOD THE PURPOSE OF ACADEMIC PROGRAM PLANNING: Planning a new academic degree program provides an opportunity for an institution to make the case for need and demand and for its ability to offer a quality program. The notification and planning activity described below do not guarantee that authorization to establish will be granted. Date: February 24, 2018 Constituent Institution: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Is the proposed program a joint degree program? Yes No X Joint Partner campus Title of Authorized Program: M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Global Africana Studies Degree Abbreviation: M.A., Ph.D. CIP Code (6-digit): Level: B M I D CIP Code Title: Does the program require one or more UNC Teacher Licensure Specialty Area Code? Yes No _ X If yes, list suggested UNC Specialty Area Code(s) here __________________________ If master’s, is it a terminal master’s (i.e. not solely awarded en route to Ph.D.)? Yes ___ No__X_ Proposed term to enroll first students in degree program: Term Fall Year 2020 Provide a brief statement from the university SACSCOC liaison regarding whether the new program is or is not a substantive change. Identify the objective of this request (select one or more of the following) ☒ Launch new program on campus ☐ Launch new program online; Maximum percent offered online ___________ ☐ Program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ One or more online courses in the program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ Launch new site-based program (list new sites below; add lines as needed) ☐ Instructor present (off-campus delivery) ☐ Instructor remote (site-based distance education) Site #1 Page 1 of 31 Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 (address, city, county, state) (max. -

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: the Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos”

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: The Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos” ABOUT AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES A SERIES OF BIANNUAL EVENTS African Perspectives is a series of conferences on Urbanism and Architecture in Africa, initiated by the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Kumasi, Ghana), University of Pretoria (South Africa), Ecole Supérieure d’Architecture de Casablanca (Morocco), Ecole Africaine des Métiers de l’Architecture et de l’Urbanisme (Lomé, Togo), ARDHI University (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania), Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) and ArchiAfrika during African Perspectives Delft on 8 December 2007. The objectives of the African Perspectives conferences are: -To bring together major stakeholders to map out a common agenda for African Architecture and create a forum for its sustainable development -To provide the opportunity for African experts in Architecture to share locally developed knowledge and expertise with each other and the broader international community -To establish a network of African experts on sustainable building and built environments for future cooperation on research and development initiatives on the continent PAST CONFERENCES INCLUDE: Casablanca, Morocco: African Perspectives 2011 Pretoria/Tshwane, South Africa: African Perspectives 2009 – The African City CENTRE: (re)sourced Delft, The Netherlands: African Perspectives 2007 - Dialogues on Urbanism and Architecture Kumasi, Ghana June 2007 - African Architecture Today Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: June 2005 - Modern Architecture in East Africa around independence 4. CONFERENCE BRIEF The Lagos Dialogues 2013 will take place at the Golden Tulip Hotel Lagos, from 5th – 8th December 2013. We invite you to attend this ground breaking international conference and dialogue on buildings, culture, and the built environment in Africa. -

Nziokim.Pdf (3.811Mb)

Differenciating dysfunction: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki 2018 Differenciating dysfunction: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions By Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. Africa Studies in the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State July 2018 Supervisor: Prof. André Keet Co-supervisor: Dr. Inge Konik Declaration I, Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki [UFS student number 2015107697], hereby declare that ‘Differenciating dysfunction’: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions is my own work, and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Further, all the sources that I have used and/or quoted within this work have been clearly indicated and acknowledged by complete references. July 2018 Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki _________________________ Table of contents Acknowledgments i Abstract ii Introduction 1 Repurposing and creative re-opening 5 Overview of chapters 10 Chapter 1: Key Concepts and Questions 14 Becoming different: Africa Rising and de-Westernisation 20 Laying out the process: Problems, questions and objectives 26 Thinking apparatus of the enemy: The burden of Nyamnjoh’s co-theorisation 34 Conceptual framework and technique of analysis 38 Cryonics of African ideas? 42 Media function of inventing: Overview of rationale for re-opening space 44 Concluding reflections on -

Media of for Africa

2019 Annual Report & Financial Statements Media of for Africa www.nationmedia.com Media of for Africa 2019 Annual Report & Financial Statements Maasai community Found in the Eastern part of Africa, the Maasai people represent the deep culture we have as a continent. They are a symbol of Africa’s cultural identity and the need to preserve it in the face of pressure from modernisation. Nation Media Group is the leading media company with businesses in print, broadcasting and digital. NMG uses its industry leading operating scale and brands to create, package and deliver high- quality content on a multi-platform basis. As the largest independent media house in East and Central Africa, we attract and serve unparalleled audiences in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda. We are committed to generating and creating content that will inform, educate and entertain our consumers across the different platforms, keeping in mind the changing needs and trends in the industry. In our journey, nothing matters more than the integrity, transparency, and balance in journalism that we have publicly committed ourselves to. NMG journalism seeks to positively transform the society it serves, by influencing social, economic and political progress. M Copyright © 2020 Nation Media Group ed ia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, o f stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any A means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, f r without the permission of the copyright holder. i 4 c a f o r A f r i c a Nation Centre, Telephone: Kimathi Street +254 20 328 8000 P.O. -

Men's Basketball

Men’s Basketball Media Guide Men’s Basketball Media Guide 03 Content Venues’ information 4 Qualifying Process for London 2012 Olympic Basketball Tournament for Men 6 Competition system 7 Schedule Men 8 GROUP A 9 Argentina 10 France 14 Lithuania 18 Nigeria 22 Tunisia 26 USA 30 GROUP B 35 Australia 36 Brazil 40 China 44 Great Britain 48 Russia 52 Spain 56 Officials 60 HISTORY 61 2011 FIBA Africa Championship for Men 61 2011 FIBA Americas Championship for Men 62 2011 FIBA Asia Championship for Men 63 EuroBasket 2011 64 2011 FIBA Oceania Championship for Men 2012 FIBA Olympic Qualifying Tournament 65 Head-to-Head 66 FIBA Events History 70 Men Olympic History 72 FIBA Ranking 74 Competition schedule Women and Men 76 If you have any questions, please contact FIBA Communications at [email protected] Publisher: FIBA Production: Norac Presse Conception & editors: Pierre-Olivier MATIGOT (BasketNews) and FIBA Communications. Designer & Layout: Thierry DESCHAMPS (Zone Presse). Copyright FIBA 2012. The reproduction and photocopying, even of extracts, or the use of articles for commercial purposes without written prior approval by FIBA is prohibited. FIBA – Fédération Internationale de Basketball - Av. Louis Casaï 53 1216 Cointrin / Geneva - Switzerland 2012 MEN’S OLYMPICS 04 LONDON, 29 JULY - 12 AUGUST Venues’ information Olympic Basketball Arena Location: North side of the Olympic Park, Stratford Year of construction: 2010-2011 Spectators: 12,000 Estimated cost: £40,000,000 One of the largest temporary sporting venues ever built, the London Olympic Basketball Arena seats 12,000 spectators and will host all basketball games from the men’s and women’s tournaments except for the Quarter-Finals of the men’s event and the Semi-finals and Finals (men and women), which will be held at the North Greenwich Arena. -

Racial Discrimination in South African Sport

Racial Discrimination in South African Sport http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1980_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Racial Discrimination in South African Sport Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 8/80 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Ramsamy, Sam Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1980-04-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1980-00-00 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Message by A.A. Ordia, President, Supreme Council for Sport in Africa. Some terms explained: Apartheid, Apartheid Sport, Banning and banning order, House arrest. -

Schools of Architecture & Africa

Gwendolen M. Carter For over 25 years the Center for African Studies at the University of Florida has organized annual lectures or a conference in honor of the late distinguished Africanist scholar, Gwendolen M. Carter. Gwendolen Carter devoted her career to scholarship and advocacy concerning the politics of inequality and injustice, especially in southern Africa. She also worked hard to foster the development of African Studies as an academic enterprise. She was perhaps best known for her pioneering study The Politics of Inequality: South Africa Since 1948 and the co-edited four-volume History of African Politics in South Africa, From Protest to Challenge (1972-1977). In the spirit of her career, the annual Carter lectures offer the university community and the greater public the perspectives of Africanist scholars on issues of pressing importance to the peoples and soci- eties of Africa. Since 2004, the Center has (with the generous support of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences) appointed Carter Faculty Fellows to serve as conveners of the conference. Schools of Architecture | Afirca: Connecting Disciplines in Design + Development 1 The Center For African Studies The Center for African Studies is in the including: languages, the humanities, the social development of international linkages. It College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at the sciences, agriculture, business, engineering, is the only National Resource Center for University of Florida. As a National Resource education, fine arts, environmental studies and Africa located in the southeastern US, and Center for African Studies, our mission is to conservation, journalism, and law. A number the only one in a sub-tropical zone. -

Media & the Africa Promise

Media & The Africa Promise Pan Africa Media Conference 2010 IMAGE & CULTURE > PARTICIPATION & INTERACTION > GOVERNANCE & DEMOCRACY > CHANGE & CRISIS > FREEDOM & RESPONSIBILITY > First published in Kenya in 2011 By Nation Media Group Acknowledgements 18-20 Kimathi Street P.O. Box 49010, Nairobi-00100 In compiling this book, I called upon the resources and talents of a number Nairobi, Kenya of close ertake this project, and his entire board directors for supporting it. I www.nationmedia.com wish to thank also Joan Pereruan, the Nation’s picture editor, for getting all the photographs together, and corporate a!airs manager David Maingi, for All rights reserved. coordinating the book’s production and printing. I must also acknowledge the No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or immeasurable input of the extremely talented Kelly Frankeny, the American transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in designer who first came to the Nation’s stable to help redesign NMG’s print writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or products. Without her deft touch, the book would have been just another run- cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition of-mill product. I must not forget the constant friendly needling of colleagues including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Charles Onyango-Obbo, Joseph Odindo and Mwikali Muthiani, to expedite the book. To all who helped in one way or another, I owe you a debt of Editors: Wangethi Mwangi assisted by Wanjiru Waithaka gratitude. -

Norms, Self-Interest and Effectiveness Explaining Double Standards in EU Reactions to Violations of Democratic Principles in Sub-Saharan Africa

Norms, self-interest and effectiveness Explaining double standards in EU reactions to violations of democratic principles in sub-Saharan Africa Karen Del Biondo Centre for EU Studies, Ghent University Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Jan Orbie Academic Year 2011-2012 Dissertation submitted with the aim to pursue the degree of „Doctor in Political Science‟ 2 Abstract The promotion of democracy has become a key objective of the European Union (EU) in sub-Saharan Africa. One of the ways in which this objective is pursued is by reacting to violations of democratic principles using negative measures: naming and shaming strategies or economic/diplomatic sanctions. Yet the application of negative measures has been criticised as being characterised by „double standards‟, meaning that similar violations of democratic principles have led to a different response from the EU. This dissertation searches for explanations for these double standards. In-depth comparative studies on the motivations for double standards in the application of negative measures in sub-Saharan Africa in the post-2000 period have been lacking. While double standards have mostly been attributed to the prevalence of self-interested objectives of the EU, this dissertation considers two additional factors: (1) a potential conflict in the EU‟s normative objectives (democracy, development and stability) and (2) expectations about the effectiveness of negative measures. These three explanatory factors (norms, self-interest and effectiveness) are investigated for ten case studies in sub-Saharan Africa: Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Guinea, Côte d‟Ivoire and Zimbabwe. It is shown that there have been double standards in the EU‟s reaction to violations of democratic principles in these countries: similar violations of democratic principles have led to different reactions from the EU (positive measures, low-cost negative measures and sanctions). -

The Political Role of the Media in the Democratisation of Malawi: the Case of the Weekend Nation from 2002 to 2012

The political role of the media in the democratisation of Malawi: The case of the Weekend Nation from 2002 to 2012 Anthony Mavuto Gunde Dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Journalism) at Stellenbosch University, Journalism Department Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Professor Simphiwe Sesanti December 2015 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2015 Copyright© 2015 Stellenbosch University All Rights Reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigated the political role of the Weekend Nation newspaper in the democratisation of Malawi between 2002 and 2012 within the context of its foundational and ownership structures by a politician. Bearing in mind that the newspaper was founded by a politician belonging to the first democratically elected ruling party, the United Democratic Front (UDF), this research sought to examine the impact of media ownership on the political role of the Weekend Nation’s journalistic practices in Malawi’s democratisation. Between 2002 and 2012, Malawi was governed by three presidents – Bakili Muluzi of the UDF from 1994 to 2004, Bingu wa Mutharika of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) from 2004 to 2012, and Joyce Banda of the People’s Party (PP) from 2012 to 2014 – all of whom were hostile to the Weekend Nation. -

Political Communications in Nigeria

-1- POLITICAL COMMUNICATIONS IN NIGERIA RAHMAN OLALEKAN OLAYIWOLA Cert. (A.I.S.) Distinction B.Sc. (Hons.), M.Sc., M.C.A., M.Phil. A Thesis in the Department of Government The London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted to the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) June 1991 UMI Number: U0B9616 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U039616 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T I 4 £ S £ S x a n o \ o -2- M A P 1 M ap of Nigeria .showing the location of tlx* muss media discussed in this thesis NIGERIA E S o k o tO ■ Katsin?^ .. a Kano B Maidugun L ,'v' ^ BKaduna Bauchi M innafl V At>u|H ; ■ I lor m ® Makurdi . B Ibadan \ . V 1^ sAb^okjJta '$ HAkurej 'N|c) ^ _ LAGO Benin Cjty On its!) a P O w ern Rivers alabar Uyo SB V ■ j Slate Boundaries ' i 7\n V y In Locations of the mass media 0 discussed in this thesis -3- POLITICAL COJOtUffICATIONS Iff NIGERIA ABSTRACT This study of the Nigerian Political Communications examines the patterns of mass media ownership and their impact on the coverage of selected national issues - the census controversy, ethnic problems and the general elections of 1979 and 1983.