Norms, Self-Interest and Effectiveness Explaining Double Standards in EU Reactions to Violations of Democratic Principles in Sub-Saharan Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: the Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-2, Issue-2, Mar-Apr- 2017 ISSN: 2456-7620 “Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: The Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C. Department of Theatre and Media Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Abstract— The private and the opposition-controlled environment where totalitarianism, dictatorship and other media have most often been taxed by Black African forms of unjust socio-political strictures reign. They are governments with being adepts of adversarial journalism. not to be intimidated or cowed by any aggressive force, to This accusation has been predicated on the observation kill stories of political actions which are inimical to public that the private media have, these last decades, tended to interest. They are rather expected to sensitize and educate dogmatically interpret their watchdog role as being an masses on sensitive socio-political issues thereby igniting enemy of government. Their adversarial inclination has the public and making it sufficiently equipped to make made them to “intuitively” suspect government and to solid developmental decisions. They are equally to play view government policies as schemes that are hardly – the role of an activist and strongly campaign for reforms nay never – designed in good faith. Based on empirical that will bring about positive socio-political revolutions in understandings, observations and secondary sources, this the society. Still as watchdogs and sentinels, the media paper argues that the same accusation may be made are expected to practice journalism in a mode that will against most Black African governments which have promote positive values and defend the interest of the overly converted the state-owned media to their public totality of social denominations co-existing in the country relation tools and as well as an arsenal to lambaste their in which they operate. -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

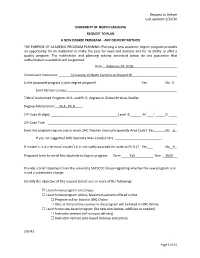

Request to Deliver Last Updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY of NORTH

Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA REQUEST TO PLAN A NEW DEGREE PROGRAM – ANY DELIVERY METHOD THE PURPOSE OF ACADEMIC PROGRAM PLANNING: Planning a new academic degree program provides an opportunity for an institution to make the case for need and demand and for its ability to offer a quality program. The notification and planning activity described below do not guarantee that authorization to establish will be granted. Date: February 24, 2018 Constituent Institution: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Is the proposed program a joint degree program? Yes No X Joint Partner campus Title of Authorized Program: M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Global Africana Studies Degree Abbreviation: M.A., Ph.D. CIP Code (6-digit): Level: B M I D CIP Code Title: Does the program require one or more UNC Teacher Licensure Specialty Area Code? Yes No _ X If yes, list suggested UNC Specialty Area Code(s) here __________________________ If master’s, is it a terminal master’s (i.e. not solely awarded en route to Ph.D.)? Yes ___ No__X_ Proposed term to enroll first students in degree program: Term Fall Year 2020 Provide a brief statement from the university SACSCOC liaison regarding whether the new program is or is not a substantive change. Identify the objective of this request (select one or more of the following) ☒ Launch new program on campus ☐ Launch new program online; Maximum percent offered online ___________ ☐ Program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ One or more online courses in the program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ Launch new site-based program (list new sites below; add lines as needed) ☐ Instructor present (off-campus delivery) ☐ Instructor remote (site-based distance education) Site #1 Page 1 of 31 Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 (address, city, county, state) (max. -

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: the Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos”

AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES 2013: The Lagos Dialogues “All Roads Lead to Lagos” ABOUT AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES A SERIES OF BIANNUAL EVENTS African Perspectives is a series of conferences on Urbanism and Architecture in Africa, initiated by the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Kumasi, Ghana), University of Pretoria (South Africa), Ecole Supérieure d’Architecture de Casablanca (Morocco), Ecole Africaine des Métiers de l’Architecture et de l’Urbanisme (Lomé, Togo), ARDHI University (Dar es Salaam, Tanzania), Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) and ArchiAfrika during African Perspectives Delft on 8 December 2007. The objectives of the African Perspectives conferences are: -To bring together major stakeholders to map out a common agenda for African Architecture and create a forum for its sustainable development -To provide the opportunity for African experts in Architecture to share locally developed knowledge and expertise with each other and the broader international community -To establish a network of African experts on sustainable building and built environments for future cooperation on research and development initiatives on the continent PAST CONFERENCES INCLUDE: Casablanca, Morocco: African Perspectives 2011 Pretoria/Tshwane, South Africa: African Perspectives 2009 – The African City CENTRE: (re)sourced Delft, The Netherlands: African Perspectives 2007 - Dialogues on Urbanism and Architecture Kumasi, Ghana June 2007 - African Architecture Today Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: June 2005 - Modern Architecture in East Africa around independence 4. CONFERENCE BRIEF The Lagos Dialogues 2013 will take place at the Golden Tulip Hotel Lagos, from 5th – 8th December 2013. We invite you to attend this ground breaking international conference and dialogue on buildings, culture, and the built environment in Africa. -

Nziokim.Pdf (3.811Mb)

Differenciating dysfunction: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki 2018 Differenciating dysfunction: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions By Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. Africa Studies in the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State July 2018 Supervisor: Prof. André Keet Co-supervisor: Dr. Inge Konik Declaration I, Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki [UFS student number 2015107697], hereby declare that ‘Differenciating dysfunction’: Domestic agency, entanglement and mediatised petitions for Africa’s own solutions is my own work, and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Further, all the sources that I have used and/or quoted within this work have been clearly indicated and acknowledged by complete references. July 2018 Mutinda (Sam) Nzioki _________________________ Table of contents Acknowledgments i Abstract ii Introduction 1 Repurposing and creative re-opening 5 Overview of chapters 10 Chapter 1: Key Concepts and Questions 14 Becoming different: Africa Rising and de-Westernisation 20 Laying out the process: Problems, questions and objectives 26 Thinking apparatus of the enemy: The burden of Nyamnjoh’s co-theorisation 34 Conceptual framework and technique of analysis 38 Cryonics of African ideas? 42 Media function of inventing: Overview of rationale for re-opening space 44 Concluding reflections on -

Media of for Africa

2019 Annual Report & Financial Statements Media of for Africa www.nationmedia.com Media of for Africa 2019 Annual Report & Financial Statements Maasai community Found in the Eastern part of Africa, the Maasai people represent the deep culture we have as a continent. They are a symbol of Africa’s cultural identity and the need to preserve it in the face of pressure from modernisation. Nation Media Group is the leading media company with businesses in print, broadcasting and digital. NMG uses its industry leading operating scale and brands to create, package and deliver high- quality content on a multi-platform basis. As the largest independent media house in East and Central Africa, we attract and serve unparalleled audiences in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda. We are committed to generating and creating content that will inform, educate and entertain our consumers across the different platforms, keeping in mind the changing needs and trends in the industry. In our journey, nothing matters more than the integrity, transparency, and balance in journalism that we have publicly committed ourselves to. NMG journalism seeks to positively transform the society it serves, by influencing social, economic and political progress. M Copyright © 2020 Nation Media Group ed ia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, o f stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any A means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, f r without the permission of the copyright holder. i 4 c a f o r A f r i c a Nation Centre, Telephone: Kimathi Street +254 20 328 8000 P.O. -

Republic of Guinea: Overcoming Growth Stagnation to Reduce Poverty

Report No. 123649-GN Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF GUINEA OVERCOMING GROWTH STAGNATION TO REDUCE POVERTY Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC March 16, 2018 International Development Association Country Department AFCF2 Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region International Finance Corporation Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD BANK GROUP IBRD IFC Regional Vice President: Makhtar Diop : Vice President: Dimitris Tsitsiragos Country Director: Soukeyna Kane Director: Vera Songwe : Country Manager: Rachidi Radji Country Manager: Cassandra Colbert Task Manager: Ali Zafar : Resident Representative: Olivier Buyoya Co-Task Manager: Yele Batana ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AGCP Guinean Central Procurement Agency ANASA Agence Nationale des Statistiques Agricoles (National Agricultural Statistics Agency) Agence de Promotion des Investissements et des Grands Travaux (National Agency for APIX Promotion of Investment and Major Works) BCRG Banque Centrale de la République de Guinée (Central Bank of Guinea) CEQ Commitment to Equity CGE Computable General Equilibrium Conseil National pour la Démocratie et le Développement (National Council for CNDD Democracy and Development) Confédération Nationale des Travailleurs de Guinée (National Confederation of CNTG Workers of Guinea) CPF Country Partnership Framework CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment CRG Crédit Rural de Guinée (Rural Credit of Guinea) CWE China Water and -

Final List of Delegations

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (21 juin 2019) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 108e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (21 June 2019) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 108th Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (21 de junio de 2019) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 108.ª reunión, Ginebra 2019 La liste des délégations est présentée sous une forme trilingue. Elle contient d’abord les délégations des Etats membres de l’Organisation représentées à la Conférence dans l’ordre alphabétique selon le nom en français des Etats. Figurent ensuite les représentants des observateurs, des organisations intergouvernementales et des organisations internationales non gouvernementales invitées à la Conférence. Les noms des pays ou des organisations sont donnés en français, en anglais et en espagnol. Toute autre information (titres et fonctions des participants) est indiquée dans une seule de ces langues: celle choisie par le pays ou l’organisation pour ses communications officielles avec l’OIT. Les noms, titres et qualités figurant dans la liste finale des délégations correspondent aux indications fournies dans les pouvoirs officiels reçus au jeudi 20 juin 2019 à 17H00. The list of delegations is presented in trilingual form. It contains the delegations of ILO member States represented at the Conference in the French alphabetical order, followed by the representatives of the observers, intergovernmental organizations and international non- governmental organizations invited to the Conference. The names of the countries and organizations are given in French, English and Spanish. Any other information (titles and functions of participants) is given in only one of these languages: the one chosen by the country or organization for their official communications with the ILO. -

Men's Basketball

Men’s Basketball Media Guide Men’s Basketball Media Guide 03 Content Venues’ information 4 Qualifying Process for London 2012 Olympic Basketball Tournament for Men 6 Competition system 7 Schedule Men 8 GROUP A 9 Argentina 10 France 14 Lithuania 18 Nigeria 22 Tunisia 26 USA 30 GROUP B 35 Australia 36 Brazil 40 China 44 Great Britain 48 Russia 52 Spain 56 Officials 60 HISTORY 61 2011 FIBA Africa Championship for Men 61 2011 FIBA Americas Championship for Men 62 2011 FIBA Asia Championship for Men 63 EuroBasket 2011 64 2011 FIBA Oceania Championship for Men 2012 FIBA Olympic Qualifying Tournament 65 Head-to-Head 66 FIBA Events History 70 Men Olympic History 72 FIBA Ranking 74 Competition schedule Women and Men 76 If you have any questions, please contact FIBA Communications at [email protected] Publisher: FIBA Production: Norac Presse Conception & editors: Pierre-Olivier MATIGOT (BasketNews) and FIBA Communications. Designer & Layout: Thierry DESCHAMPS (Zone Presse). Copyright FIBA 2012. The reproduction and photocopying, even of extracts, or the use of articles for commercial purposes without written prior approval by FIBA is prohibited. FIBA – Fédération Internationale de Basketball - Av. Louis Casaï 53 1216 Cointrin / Geneva - Switzerland 2012 MEN’S OLYMPICS 04 LONDON, 29 JULY - 12 AUGUST Venues’ information Olympic Basketball Arena Location: North side of the Olympic Park, Stratford Year of construction: 2010-2011 Spectators: 12,000 Estimated cost: £40,000,000 One of the largest temporary sporting venues ever built, the London Olympic Basketball Arena seats 12,000 spectators and will host all basketball games from the men’s and women’s tournaments except for the Quarter-Finals of the men’s event and the Semi-finals and Finals (men and women), which will be held at the North Greenwich Arena. -

Racial Discrimination in South African Sport

Racial Discrimination in South African Sport http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1980_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Racial Discrimination in South African Sport Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 8/80 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid; Ramsamy, Sam Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1980-04-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1980-00-00 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description Message by A.A. Ordia, President, Supreme Council for Sport in Africa. Some terms explained: Apartheid, Apartheid Sport, Banning and banning order, House arrest. -

Schools of Architecture & Africa

Gwendolen M. Carter For over 25 years the Center for African Studies at the University of Florida has organized annual lectures or a conference in honor of the late distinguished Africanist scholar, Gwendolen M. Carter. Gwendolen Carter devoted her career to scholarship and advocacy concerning the politics of inequality and injustice, especially in southern Africa. She also worked hard to foster the development of African Studies as an academic enterprise. She was perhaps best known for her pioneering study The Politics of Inequality: South Africa Since 1948 and the co-edited four-volume History of African Politics in South Africa, From Protest to Challenge (1972-1977). In the spirit of her career, the annual Carter lectures offer the university community and the greater public the perspectives of Africanist scholars on issues of pressing importance to the peoples and soci- eties of Africa. Since 2004, the Center has (with the generous support of the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences) appointed Carter Faculty Fellows to serve as conveners of the conference. Schools of Architecture | Afirca: Connecting Disciplines in Design + Development 1 The Center For African Studies The Center for African Studies is in the including: languages, the humanities, the social development of international linkages. It College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at the sciences, agriculture, business, engineering, is the only National Resource Center for University of Florida. As a National Resource education, fine arts, environmental studies and Africa located in the southeastern US, and Center for African Studies, our mission is to conservation, journalism, and law. A number the only one in a sub-tropical zone. -

List of Affiliated Organisations

ITUC INTERNATIONAL TRADE UNION CONFEDERATION CSI CONFÉDÉRATION SYNDICALE INTERNATIONALE CSI CONFEDERACIÓN SINDICAL INTERNACIONAL IGB INTERNATIONALER GEWERKSCHAFTSBUND LIST OF AFFILIATED ORGANISATIONS Country or Territory Organisation Membership 1 Afganistan 1 National Union of Afghanistan Workers and Employees (NUAWE) 120,000 2 Albania 2 Confederation of the Trade Unions of Albania (KSSH) 110,000 3 Union of the Independent Trade Unions of Albania (BSPSH) 84,000 3 Algeria 4 Union Générale des Travailleurs Algériens (UGTA) 1,875,520 4 Angola 5 Central Geral de Sindicatos Independentes e Livres de Angola (CGSILA) 93,000 6 União Nacional dos Trabalhadores de Angola (UNTA- CS) 215,548 5 Antigua and Barbuda 7 Antigua & Barbuda Public Service Association (ABPSA) 365 8 Antigua & Barbuda Workers' Union (ABWU) 3,000 6 Argentina 9 Central de los Trabajadores Argentinos (CTA) 600,000 10 Confederación General del Trabajo de la República Argentina (CGT) 4,401,023 7 Armenia 11 Confederation of Trade Unions of Armenia (KPA) 237,000 8 Aruba 12 Federacion di trahadornan di Aruba (FTA) 2,507 9 Australia 13 Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) 1,761,400 10 Austria 14 Österreichischer Gewerkschaftsbund (ÖGB) 1,222,190 11 Azerbaijan 15 Azerbaycan Hemkarlar Ittifaqlari Konfederasiyasi (AHIK) 735,000 12 Bahrain 16 General Federation of Bahrain Trade Unions (GFBTU) 10,000 13 Bangladesh 17 Bangladesh Free Trade Union Congress (BFTUC) 85,000 18 Bangladesh Jatyatabadi Sramik Dal (BJSD) 180,000 19 Bangladesh Labour Federation (BLF) 102,000 20 Bangladesh Mukto