Political Communications in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Book-91249.Pdf

THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? By SHINA L. F. AMACHIGH " Bachelor of Arts Ahmadu Bello University Samaru-Zaria, Nigeria 1979 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Col lege of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1986 THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1251198 i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My foremost thanks go to my heavenly Father, the Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit for the completion of this study. Thank you, Dr. Lawler (committee chair), for your guidance and as sistance and for letting me use a dozen or so of your personal textbooks throughout the duration of this study. Appreciation is also expressed to the other committee members, Drs. von Sauer and Sare, for their in valuable assistance in preparation of the final manuscript. Thank you, Ruby and Amen (my wife and son) for not fussing all the times I had to be 11 gone again. 11 I love you. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I • INTRODUCTION Backqround 1 The Problem 2 Thesis and Purpose 2 Analytical Framework and Methodology 3 I I. REVIEW OF THEORETICAL LITERATURE 5 The Ataturk Model ....• 16 The Origins of Military Intervention 18 Africa South of the Sahara .... 20 I II. BRIEF HISTORY OF MILITARY INVOLVEMENT IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979) 23 IV. THE PROBLEM OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION 29 British Colonialism and National Inte- gration in Nigeria .... -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

SPECIAL REPORT on Nigeria's

Special RepoRt on nIgeria’s BENUe s t A t e BENUE STATE: FACTS AND FIGURES Origin: Benue State derives its name from the River Benue, the second largest river in Nigeria and the most prominent geographical feature in the state Date of creation: February 1976 Characteristics: Rich agricultural region; full of rivers, breadbasket of Nigeria. Present Governor: Chief George Akume Population: 5 million Area: 34,059 sq. kms Capital: Makurdi Number of local government: 23 Traditional councils: Tiv Traditional Council, headed by the Tor Tiv; and Idoma Traditional Council, headed by the Och’Idoma. Location: Lies in the middle of the country and shares boundaries with Cameroon and five states namely, Nasarawa to the north, Taraba to the east, Cross River and Enugu to the south, and Kogi to the west Climate: A typical tropical climate with two seasons – rainy season from April to October in the range of 150-180 mm, and the dry season from November to March. Temperatures fluctuate between 23 degrees centigrade to 31 degrees centigrade in the year Main Towns: Makurdi (the state capital), Gboko, Katsina-Ala, Adikpo, Otukpo, Korinya, Tar, Vaneikya, Otukpa, Oju, Okpoga, Awajir, Agbede, Ikpayongo, and Zaki-Biam Rivers: Benue River and Katsina Ala Culture and tourism: A rich and diverse cultural heritage, which finds expression in colourful cloths, exotic masquerades, music and dances. Benue dances have won national and international acclaim, including the Swange and the Anuwowowo Main occupation: Farming Agricultural produce: Grains, rice, cassava, sorghum, soya beans, beniseed (sesame), groundnuts, tubers, fruits, and livestock Mineral resources: Limestone, kaolin, zinc, lead, coal, barites, gypsum, Feldspar and wolframite for making glass and electric bulbs, and salt Investment policies: Government has a liberal policy of encouraging investors through incentives and industrial layout, especially in the capital Makurdi, which is served with paved roads, water, electricity and telephone. -

From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940

The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History ISSN: 0308-6534 (Print) 1743-9329 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fich20 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly To cite this article: Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2019) From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 47:3, 474-489, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 Published online: 15 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fich20 THE JOURNAL OF IMPERIAL AND COMMONWEALTH HISTORY 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 474–489 https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Indirect rule figured prominently in Nigeria’s colonial Nigeria; Abeokuta; crime; administration, but historians understand more about the police; indirect rule abstract tenets of this administrative strategy than they do about its everyday implementation. This article investigates the early history of the Native Authority Police Force in the town of Abeokuta in order to trace a larger move towards coercive forms of administration in the early twentieth century. In this period the police in Abeokuta developed from a primarily civil force tasked with managing crime in the rapidly growing town, into a political implement of the colonial government. -

Nigerian Nationalism: a Case Study in Southern Nigeria, 1885-1939

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1972 Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939 Bassey Edet Ekong Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ekong, Bassey Edet, "Nigerian nationalism: a case study in southern Nigeria, 1885-1939" (1972). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 956. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF' THE 'I'HESIS OF Bassey Edet Skc1::lg for the Master of Arts in History prt:;~'entE!o. 'May l8~ 1972. Title: Nigerian Nationalism: A Case Study In Southern Nigeria 1885-1939. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITIIEE: ranklln G. West Modern Nigeria is a creation of the Britiahl who be cause of economio interest, ignored the existing political, racial, historical, religious and language differences. Tbe task of developing a concept of nationalism from among suoh diverse elements who inhabit Nigeria and speak about 280 tribal languages was immense if not impossible. The tra.ditionalists did their best in opposing the Brltlsh who took away their privileges and traditional rl;hts, but tbeir policy did not countenance nationalism. The rise and growth of nationalism wa3 only po~ sible tbrough educs,ted Africans. -

“Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: the Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-2, Issue-2, Mar-Apr- 2017 ISSN: 2456-7620 “Watchdogging” Versus Adversarial Journalism by State-Owned Media: The Nigerian and Cameroonian Experience Endong Floribert Patrick C. Department of Theatre and Media Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Abstract— The private and the opposition-controlled environment where totalitarianism, dictatorship and other media have most often been taxed by Black African forms of unjust socio-political strictures reign. They are governments with being adepts of adversarial journalism. not to be intimidated or cowed by any aggressive force, to This accusation has been predicated on the observation kill stories of political actions which are inimical to public that the private media have, these last decades, tended to interest. They are rather expected to sensitize and educate dogmatically interpret their watchdog role as being an masses on sensitive socio-political issues thereby igniting enemy of government. Their adversarial inclination has the public and making it sufficiently equipped to make made them to “intuitively” suspect government and to solid developmental decisions. They are equally to play view government policies as schemes that are hardly – the role of an activist and strongly campaign for reforms nay never – designed in good faith. Based on empirical that will bring about positive socio-political revolutions in understandings, observations and secondary sources, this the society. Still as watchdogs and sentinels, the media paper argues that the same accusation may be made are expected to practice journalism in a mode that will against most Black African governments which have promote positive values and defend the interest of the overly converted the state-owned media to their public totality of social denominations co-existing in the country relation tools and as well as an arsenal to lambaste their in which they operate. -

First Bank of Nigeria Plc Head Office: 35, Samuel Asabia House, Marina, Lagos First Bank of Nigeria Plc | Annual Report & Accounts 2009

First Bank of Nigeria Plc Head Office: 35, Samuel Asabia House, Marina, Lagos www.firstbanknigeria.com First Bank of Nigeria Plc | Annual Report & Accounts 2009 Registration No. RC6290 First Bank of Nigeria Plc | Annual Report & Accounts 2009 ABBREVIATIONS ALCO – Assets & Liabilities Management Committee KRI – Key Risk Indicator ATM – Automated Teller Machine LAD – Loans and Advances BARAC – Board Audit and Risk Assessment Committee LASACS – Large Scale Agricultural Credit Scheme BDO – Business Development Office mbd – million barrels a day ANNUAL CAGR – Cumulative Annual Growth Rate MDAs – Ministries, Departments and Agencies CAM – Classified Assets Management Dept MFBs – Microfinance Banks CAP – Credit Analysis & Processing Dept MFR – Member of the Order of the Federal Republic CBN – Central Bank of Nigeria mni – Member National Institute CCO – Chief Compliance Officer MPA – Mortgage Plan Account CON – Commander of the Order of the Niger MPC – Monetary Policy Committee REPORT CPFA – Close Pension Fund Administrator MPR – Monetary Policy Rate CRM – Credit Risk Management N – Naira CRO – Chief Risk Officer NSE – Nigerian Stock Exchange CSA – Children Savings Account OFR – Officer of the Federal Republic CSCS – Central Securities Clearing System OPL – Open Position Limit CSR – Corporate Social Responsibility ORM – Operational Risk Management Division ACCOUNTSIntroduction 2 Business Review 23 & EAR – Earnings At Risk OTC – Over The Counter Financial Highlights 2 Operating Environment 24 Chairman’s Statement 4 Industry Review and Outlook -

Legislative Control of the Executive in Nigeria Under the Second Republic

04, 03 01 AWO 593~ By AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK B.A. (HONS) (ABU) M.Sc. (!BADAN) Thesis submitted to the Department of Public Administration Faculty of Administration in Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of --~~·---------.---·-.......... , Progrnmme c:~ Petites Subventions ARRIVEE - · Enregistré sous lo no l ~ 1 ()ate :. Il fi&~t. JWi~ DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PUBLIC ADMIJISTRATION) Obafemi Awolowo University, CE\/ 1993 1le-Ife, Nigeria. 2 3 r • CODESRIA-LIBRARY 1991. CERTIFICATION 1 hereby certify that this thesis was prepared by AWOTOKUN, ADEKUNLE MESHACK under my supervision. __ _I }J /J1,, --- Date CODESRIA-LIBRARY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A work such as this could not have been completed without the support of numerous individuals and institutions. 1 therefore wish to place on record my indebtedness to them. First, 1 owe Professer Ladipo Adamolekun a debt of gratitude, as the persan who encouraged me to work on Legislative contrai of the Executive. He agreed to supervise the preparation of the thesis and he did until he retired from the University. Professor Adamolekun's wealth of academic experience ·has no doubt sharpened my outlciok and served as a source of inspiration to me. 1 am also very grateful to Professor Dele Olowu (the Acting Head of Department) under whose intellectual guidance I developed part of the proposai which culminated ·in the final production qf .this work. My pupilage under him i though short was memorable and inspiring. He has also gone through the entire draft and his comments and criticisms, no doubt have improved the quality of the thesis. Perhaps more than anyone else, the Almighty God has used my indefatigable superviser Dr. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

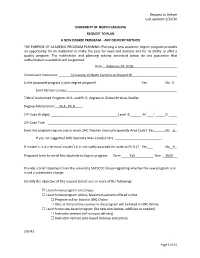

Request to Deliver Last Updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY of NORTH

Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA REQUEST TO PLAN A NEW DEGREE PROGRAM – ANY DELIVERY METHOD THE PURPOSE OF ACADEMIC PROGRAM PLANNING: Planning a new academic degree program provides an opportunity for an institution to make the case for need and demand and for its ability to offer a quality program. The notification and planning activity described below do not guarantee that authorization to establish will be granted. Date: February 24, 2018 Constituent Institution: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Is the proposed program a joint degree program? Yes No X Joint Partner campus Title of Authorized Program: M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Global Africana Studies Degree Abbreviation: M.A., Ph.D. CIP Code (6-digit): Level: B M I D CIP Code Title: Does the program require one or more UNC Teacher Licensure Specialty Area Code? Yes No _ X If yes, list suggested UNC Specialty Area Code(s) here __________________________ If master’s, is it a terminal master’s (i.e. not solely awarded en route to Ph.D.)? Yes ___ No__X_ Proposed term to enroll first students in degree program: Term Fall Year 2020 Provide a brief statement from the university SACSCOC liaison regarding whether the new program is or is not a substantive change. Identify the objective of this request (select one or more of the following) ☒ Launch new program on campus ☐ Launch new program online; Maximum percent offered online ___________ ☐ Program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ One or more online courses in the program will be listed in UNC Online ☐ Launch new site-based program (list new sites below; add lines as needed) ☐ Instructor present (off-campus delivery) ☐ Instructor remote (site-based distance education) Site #1 Page 1 of 31 Request to Deliver Last updated 1/12/16 (address, city, county, state) (max.