Observations on the Sodium and Potassium Content of Mucus from the Large Intestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

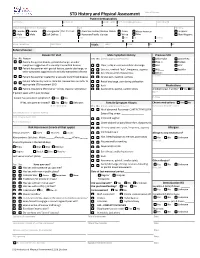

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref. name/AKA/pronoun Date of Birth Sex (at birth) Gender (all that apply Race Ethnicity Female Female Transgender Pref. Pronoun: American Indian/Alaskan Native Asian African American Hispanic Male Male Self Define: Hawaiian/Pacific Islander White Other Non-Hispanic Street Address City State Zip County Home Telephone Cell Phone Vitals: Temp: Pulse: RR: BP: Referral Source: Reason for Visit Male Symptom History Previous STD Yes No Reason Yes No (check appropriate boxes) Chlamydia Gonorrhea Patient has genital lesions, genital discharge, or other Hep. C Herpes symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Clear, milky or mucoid urethral discharge HIV HPV Patient has partner with genital lesions, genital discharge, or Dysuria , urethral “itch”, frequency, urgency PID Syphilis other symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Sore throat and/or hoarseness Other: Patient has partner treated for a sexually transmitted disease Scrotal pain, swelling, redness Comments: Patient referred by local or state DIS. Review labs and refer to Rectal discharge, pain during defecation appropriate STD treatment SDO Rash Medications Patient requesting STD testing – denies reasons listed above Asymmetric, painful, swollen joints Antibiotics last 4 weeks? Yes No If patient seen within past 30 days: Name Purpose Patient has persistent symptoms? Yes No If Yes, was partner treated? Yes No Unknown Female Symptom History Chronic medications -

Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 64 / No. 3 June 5, 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Gonococcal Infections ...................................................................................... 60 Methods ....................................................................................................................1 Diseases Characterized by Vaginal Discharge .......................................... 69 Clinical Prevention Guidance ............................................................................2 Bacterial Vaginosis .......................................................................................... 69 Special Populations ..............................................................................................9 Trichomoniasis ................................................................................................. 72 Emerging Issues .................................................................................................. 17 Vulvovaginal Candidiasis ............................................................................. 75 Hepatitis C ......................................................................................................... 17 Pelvic Inflammatory -

ESMO Colorectal Cancer Guide for Patients English

Colorectal Cancer What is colorectal cancer? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines COLORECTAL CANCER: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of colorectal cancer and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of colorectal cancer. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of colorectal cancer. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the leading author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals. It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Colorectal Cancer: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines - v.2016.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya

Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya Table of Contents Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya..................................1 FOREWORD..........................................................................................................................................3 PREFACE...............................................................................................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................................................5 1. ACUTE INJURIES AND TRAUMA & SELECTED EMERGENCIES..................................................7 1.1. Anaphylaxis & Cardiac Arrest...................................................................................................7 1.2. Abdominal Trauma....................................................................................................................8 1.3. Bites & Rabies.........................................................................................................................10 1.4. Burns.......................................................................................................................................13 1.5. Disaster Plan...........................................................................................................................16 -

Rectal Prolapse: an Overview of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Patient-Specific Management Strategies

J Gastrointest Surg (2014) 18:1059–1069 DOI 10.1007/s11605-013-2427-7 EVIDENCE-BASED CURRENT SURGICAL PRACTICE Rectal Prolapse: An Overview of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Patient-Specific Management Strategies Liliana Bordeianou & Caitlin W. Hicks & Andreas M. Kaiser & Karim Alavi & Ranjan Sudan & Paul E. Wise Received: 11 November 2013 /Accepted: 27 November 2013 /Published online: 19 December 2013 # 2013 The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract Abstract Rectal prolapse can present in a variety of forms and is associated with a range of symptoms including pain, incomplete evacuation, bloody and/or mucous rectal discharge, and fecal incontinence or constipation. Complete external rectal prolapse is characterized by a circumferential, full-thickness protrusion of the rectum through the anus, which may be intermittent or may be incarcerated and poses a risk of strangulation. There are multiple surgical options to treat rectal prolapse, and thus care should be taken to understand each patient’s symptoms, bowel habits, anatomy, and pre-operative expectations. Preoperative workup includes physical exam, colonoscopy, anoscopy, and, in some patients, anal manometry and defecography. With this information, a tailored surgical approach (abdominal versus perineal, minimally invasive versus open) and technique (posterior versus ventral rectopexy +/− sigmoidectomy, for example) can then be chosen. We propose an algorithm based on available outcomes data in the literature, an understanding of anorectal physiology, and expert opinion that can serve as a guide to determining the rectal prolapse operation that will achieve the best possible postoperative outcomes for individual patients. Keywords Rectal prolapse . Management . Surgery . ’ . Liliana Bordeianou and Caitlin W. Hicks are co-first authors. -

MEC Logo Proctitis

DINESH JAIN, M.D. RAVI NADIMPALLI, M.D. SCOTT BERGER, M.D. JENNIFER FRANKEL, M.D. SUSHAMA GUNDLAPALLI, M.D. GONZALO PANDOLFI, M.D. DARREN KASTIN, M.D. 1243 Rickert Dr. Telephone 630-527-6450 Naperville, IL 60540 Fax 630-527-6456 SGIHealth.com Proctitis What is proctitis? Proctitis is inflammation of the lining of the rectUm, the lower end of the large intestine leading to the anUs. The large intestine and anUs are part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the moUth to the anUs. The movement of mUscles in the GI tract, along with the release of hormones and enzymes, allows for the digestion of food. With proctitis, inflammation of the rectal lining—called the rectal mUcosa—is Uncomfortable and sometimes painfUl. The condition may lead to bleeding or mUcoUs discharge from the rectum, among other symptoms. What causes proctitis? Proctitis has many caUses, inclUding acUte, or sUdden and short-term, and chronic, or long-lasting, conditions. Among the causes are the following: Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). STDs that can be passed when a person is receiving anal sex are a common caUse of proctitis. Common STD infections that can caUse proctitis inclUde gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and herpes. Herpes-indUced proctitis may be particUlarly severe in people who are also infected with the HIV virUs. Non-STD infections. Infections that are not sexUally transmitted also can caUse proctitis. Salmonella and Shigella are examples of foodborne bacteria that can cause proctitis. Streptococcal proctitis sometimes occurs in children who have strep throat. -

Colon Cancer During Pregnancy: a Report of Two Cases

Case Series Annals of Clinical Case Reports Published: 24 Jan, 2020 Colon Cancer during Pregnancy: A Report of Two Cases Dobrokhotova Y1, Danelian S2 and Borovkova E1* 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Russian National Research Medical University, Russia 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, City Clinical Hospital No. 40, Russia Abstract Background: Colorectal Cancer (CRC) is exceedingly rare in pregnancy, estimated to occur in 1 in 13000 pregnancies. CRC symptoms such as abdominal pain, constipation, nausea, and vomiting are usually attributed to the physiological changes of pregnancy. Case Presentation: A 30-year-old woman at 23-24 weeks of gestation presented with abdominal discomfort, constipation, and bloody rectal discharge. A 34-year-old woman at 27-28 weeks of gestation delivered to the emergency room with the episode of unconsciousness and involuntary urination. Both patients underwent the MRI examination without contrast. MRI scanning showed a formation of the sigmoid colon without obstruction and a cystic-solid formation of the right ovary (in the first patient) and formations of the frontal-parietal lobe, multiple hepatic metastases, and the tumour of the ampullary rectum with stenosis (in the second patient). The diagnosis of the sigmoid and rectal adenocarcinoma was estimated in both women via performing the colonoscopy with biopsy. After the neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX was done, doctors performed surgical operations as follows: the laparotomy, caesarean section, panhysterectomy, hemicolectomy with descendo-rectal anastomosis, and pelvic lymphody section for the first patient (performed on 33 gestation week due to increase of the size of metastasis in ovary); caesarean section for the second patient (performed on the 33 gestation week of pregnancy due to the fetal stress). -

(SICCR): Management and Treatment of Complete Rectal Prolapse

Techniques in Coloproctology (2018) 22:919–931 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-018-1908-9 REVIEW ARTICLE Consensus Statement of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR): management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse G. Gallo1,2 · J. Martellucci3 · G. Pellino4,5 · R. Ghiselli6 · A. Infantino7 · F. Pucciani8 · M. Trompetto1 Received: 15 November 2018 / Accepted: 9 December 2018 / Published online: 15 December 2018 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Abstract Rectal prolapse, rectal procidentia, “complete” prolapse or “third-degree” prolapse is the full-thickness prolapse of the rectal wall through the anal canal and has a significant impact on quality of life. The incidence of rectal prolapse has been estimated to be approximately 2.5 per 100,000 inhabitants with a clear predominance among elderly women. The aim of this consen- sus statement was to provide evidence-based data to allow an individualized and appropriate management and treatment of complete rectal prolapse. The strategy used to search for evidence was based on application of electronic sources such as MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Review Library, CINAHL and EMBASE. The recommendations were defined and graded based on the current levels of evidence and in accordance with the criteria adopted by the American College of Gastroenterol- ogy’s Chronic Constipation Task Force. Five evidence levels were defined. The recommendations were graded A, B, and C. Keywords External rectal prolapse · Rectal procidentia · Non-operative management · Surgical treatment · Abdominal approach · Perineal approach Introduction External rectal prolapse, rectal procidentia, or “complete” prolapse, can be defined as a circumferential, full-thickness intussusception of the rectal wall which protrudes outside the anal canal [1]. -

Partner Services Providers Quick Guide This Pamphlet Is Meant for Use by Disease Intervention Specialists and Others Conducting Partner Services Activities

Partner Services Providers Quick Guide This pamphlet is meant for use by Disease Intervention Specialists and others conducting partner services activities. High Priority Index Patients for Partner Services • Pregnant women • Male index patients known to have pregnant female partners • Index patients suspected of (or known to be) engaging in behaviors that significantly increase the risk for transmission to multiple other persons • Persons co-infected with HIV and one or more other STDs • Persons with recurrent STDs • P ersons who present with clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of infection • Cases from core areas – for gonorrhea, prioritizing cases from core areas may offer an opportunity to reduce transmission at the community level • Persons with high HIV viral load (e.g., >50,000 copies RNA/mL) – high serum viral load is associated with increased risk for HIV transmission • Persons with evidence of acute infection or recent infection High Priority Patients Management Tips Effective Case Management Tips • Conduct pre/post interview analysis • Take notes and review them with the VCA • Write up case quickly while information is still fresh • Review VCA regularly • Respond to supervisor comments • Review case daily • Maintain good organization • Debrief case (peers, supervisor, etc.) • Re-interview patient as soon as possible DISEASE INTERVIEW PERIODS* Chlamydial infection Symptomatic . 60 days before onset of symptoms through date of treatment Asymptomatic . 60 days before date of specimen collection (through date of treatment if patient was not treated at time specimen was collected) Gonorrhea Symptomatic . 60 days before onset of symptoms through date of treatment Asymptomatic . 60 days before date of specimen collection (through date of treatment if patient was not treated at time specimen was collected) * The time interval for which an index patient is asked to recall sex or drug-injection partners. -

Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome in Children: a Report of Six Cases

Gut and Liver, Vol. 7, No. 6, November 2013, pp. 752-755 BRIEF COMMUNICATION Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome in Children: A Report of Six Cases Nafiye Urgancı*, Derya Kalyoncu†, and Kamile Gulcin Eken‡ *Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Departments of †Pediatrics, and ‡Pathology, Sisli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare, benign dis- diseases such as inflammatory bowel diseases, amebiasis, ma- order in children that usually presents with rectal bleeding, lignancy, and other causes of rectal bleeding such as a juvenile constipation, mucous discharge, prolonged straining, tenes- polyp.2,5,9,19,20 SRUS should be suspected in patients with rectal mus, lower abdominal pain, and localized pain in the perine- discharge of blood and mucus and previous disorders of evacu- al area. The underlying etiology is not well understood, but it ation. We report herein six pediatric cases with SRUS for re- is secondary to ischemic changes and trauma in the rectum minding this rare syndrome. associated with paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor and the external anal sphincter muscles; rectal prolapse has CASE REPORTS also been implicated in the pathogenesis. This syndrome is 1. Case 1 diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and endoscopic and histological findings, but SRUS often goes unrecognized or A 10-year-old boy was referred to our pediatric gastroenterol- is easily confused with other diseases such as inflammatory ogy unit with rectal bleeding. He had had episodes of diarrhea, bowel disease, amoebiasis, malignancy, and other causes sometimes bloody, during 10 years. Diarrhea had worsened of rectal bleeding such as a juvenile polyps. -

Diseases and Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

CHAPTER 1 Esophagus. is unknown, and healing generally occurs DISEASES AND DISORDERS OF THE Stomach. spontaneously within 10 days to two weeks. Small intestine. Aphthous stomatitis is most common in young GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT (10 CONTACT HOURS) Large intestine. girls and female teenagers. Its cause is unknown, Rectum. but stress, fatigue, anxiety and fever predispose Learning objectives: Anal canal. its development. Treatment is geared to symptom ! Review the anatomy of the gastrointestinal relief through the use of a topical anesthetic and The accessory glands and organs consist of the system. reduction of predisposing factors.5 salivary glands, liver, gallbladder and bile ducts ! Describe diseases of the oral cavity. and the pancreas.9 The major functions of the GI Miscellaneous infections ! Identify treatment of diseases of the oral system are digestion and elimination of waste Candidiasis (thrush): Fungal infection cavity. products from the body.5,9 that causes cream or bluish-white patches ! Explain the types of disorders and diseases of exudates to appear on the tongue, mouth, affecting the esophagus. Diseases and disorders of the GI system can and/or pharynx. Persons at high risk include ! Evaluate treatment initiatives for disorders range from mild annoyances to life-threatening premature neonates, older adults, those and diseases affecting the esophagus. conditions. It is important that the nurse with suppressed immune systems, persons ! Identify pathophysiology of gastric diseases recognize the numerous abnormalities that can taking antibiotics, or persons taking steroids and disorders. occur, and how to most effectively intervene to for a long period of time. For infants, the ! Evaluate treatment initiatives for gastric help the patient return to a state of maximum oral mucosa is swabbed with nystatin after diseases and disorders. -

John Doe DOB: XX/XX/XXXX 1 of 48 MEDICAL

John Doe DOB: XX/XX/XXXX MEDICAL CHRONOLOGY - INSTRUCTIONS TO FOLLOW General Instructions: Brief Summary/Flow of Events: In the beginning of the chronology, a Brief Summary/Flow of Events outlining the significant medical events is provided which will give a general picture of the focus points in the case. Patient History: Details related to the patient’s past history (medical, surgical, social, and family history) present in the medical records. Detailed Medical Chronology: Information captured “as it is” in the medical records without alteration of the meaning. Type of information capture (all details/zoom-out model and relevant details/zoom-in model) is as per the demands of the case which will be elaborated under the ‘Specific Instructions. Reviewer’s Comments: Comments on contradicting information and misinterpretations in the medical records, illegible handwritten notes, missing records, clarifications needed etc. are given in italics and red font color and will appear as * Reviewer’s Comment Illegible Dates: Illegible and missing dates are presented as “00/00/0000” (mm/dd/yyyy format) Illegible Notes: Illegible handwritten notes are left as a blank space “_____” with a note as “Illegible Notes” in the heading of the particular consultation/report, areas which we have interpreted but are doubtful are presented in red italics. Specific Instructions: • The chronology focuses on clinical condition pertaining to Hirschsprung’s disease and the surgical management as given below: ➢ XX/XX/2016- XX/XX/2016: These hospitalization records summarized in detail from the initial presentation, diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease, surgical management of transanal pull through on XX/XX/2016 and postoperative complication rectovaginal fistula along with its management till discharge on XX/XX/2016.