Rectal Prolapse: an Overview of Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Patient-Specific Management Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Congenital Megacolon with Acute Fecal Obstruction and Diabetic Nephropathy: a Case Report

2726 EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 18: 2726-2730, 2019 Adult congenital megacolon with acute fecal obstruction and diabetic nephropathy: A case report MINGYUAN ZHANG1,2 and KEFENG DING1 1Colorectal Surgery Department, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310000; 2Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Yinzhou Peoples' Hospital, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315000, P.R. China Received November 27, 2018; Accepted June 20, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7852 Abstract. Megacolon is a congenital disorder. Adult congen- sufficient amount of bowel should be removed, particularly the ital megacolon (ACM), also known as adult Hirschsprung's aganglionic segment (2). The present study reports on a case of disease, is rare and frequently manifests as constipation. ACM a 56-year-old patient with ACM, fecal impaction and diabetic is caused by the absence of ganglion cells in the submucosa nephropathy. or myenteric plexus of the bowel. Most patients undergo treat- ment of megacolon at a young age, but certain patients cannot Case report be treated until they develop bowel obstruction in adulthood. Bowel obstruction in adults always occurs in complex clinical A 56-year-old male patient with a history of chronic constipa- situations and it is frequently combined with comorbidities, tion presented to the emergency department of Yinzhou including bowel tumors, volvulus, hernias, hypertension or Peoples' Hospital (Ningbo, China) in February 2018. The diabetes mellitus. Surgical intervention is always required in patient had experienced vague abdominal distention for such cases. To avoid recurrence, a sufficient amount of bowel several days. Prior to admission, chronic bowel obstruction should be removed, particularly the aganglionic segment. -

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction Prof. Marek Jackowski Definition • Any condition interferes with normal propulsion and passage of intestinal contents. • Can involve the small bowel, colon or both small and colon as in generalized ileus. Definitions 5% of all acute surgical admissions Patients are often extremely ill requiring prompt assessment, resuscitation and intensive monitoring Obstruction a mechanical blockage arising from a structural abnormality that presents a physical barrier to the progression of gut contents. Ileus a paralytic or functional variety of obstruction Obstruction: Partial or complete Simple or strangulated Epidemiology 1 % of all hospitalization 3-5 % of emergency surgical admissions More frequent in female patients - gynecological and pelvic surgical operations are important etiologies for postop. adhesions Adhesion is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction 80% of bowel obstruction due to small bowel obstruction - the most common causes are: - Adhesion - Hernia - Neoplasm 20% due to colon obstruction - the most common cause: - CR-cancer 60-70%, - diverticular disease and volvulus - 30% Mortality rate range between 3% for simple bowel obstruction to 30% when there is strangulation or perforation Recurrent rate vary according to method of treatment ; - conservative 12% - surgical treatment 8-32% Classification • Cause of obstruction: mechanical or functional. • Duration of obstruction: acute or chronic. • Extent of obstruction: partial or complete • Type of obstruction: simple or complex (closed loop and strangulation). CLASSIFICATION DYNAMIC ADYNAMIC (MECHANICAL) (FUNCTIONAL) Peristalsis is Result from atony of working against a the intestine with loss mechanical of normal peristalsis, obstruction in the absence of a mechanical cause. or it may be present in a non-propulsive form (e.g. mesenteric vascular occlusion or pseudo-obstruction) Etiology Mechanical bowel obstruction: A. -

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Similarities and Differences 2 www.ccfa.org IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 Important Differences Between IBD and IBS Many diseases and conditions can affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system and includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. These diseases and conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 www.ccfa.org 3 Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflammatory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflamma- Causes tory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. The two most com- The exact cause of IBD remains unknown. Researchers mon inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease believe that a combination of four factors lead to IBD: a (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD affects as many as 1.4 genetic component, an environmental trigger, an imbal- million Americans, most of whom are diagnosed before ance of intestinal bacteria and an inappropriate reaction age 35. There is no cure for IBD but there are treatments to from the immune system. Immune cells normally protect reduce and control the symptoms of the disease. the body from infection, but in people with IBD, the immune system mistakes harmless substances in the CD and UC cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. CD intestine for foreign substances and launches an attack, can affect any part of the GI tract, but frequently affects the resulting in inflammation. -

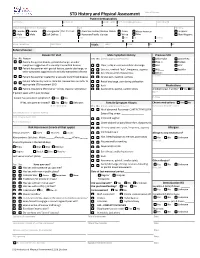

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref. name/AKA/pronoun Date of Birth Sex (at birth) Gender (all that apply Race Ethnicity Female Female Transgender Pref. Pronoun: American Indian/Alaskan Native Asian African American Hispanic Male Male Self Define: Hawaiian/Pacific Islander White Other Non-Hispanic Street Address City State Zip County Home Telephone Cell Phone Vitals: Temp: Pulse: RR: BP: Referral Source: Reason for Visit Male Symptom History Previous STD Yes No Reason Yes No (check appropriate boxes) Chlamydia Gonorrhea Patient has genital lesions, genital discharge, or other Hep. C Herpes symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Clear, milky or mucoid urethral discharge HIV HPV Patient has partner with genital lesions, genital discharge, or Dysuria , urethral “itch”, frequency, urgency PID Syphilis other symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Sore throat and/or hoarseness Other: Patient has partner treated for a sexually transmitted disease Scrotal pain, swelling, redness Comments: Patient referred by local or state DIS. Review labs and refer to Rectal discharge, pain during defecation appropriate STD treatment SDO Rash Medications Patient requesting STD testing – denies reasons listed above Asymmetric, painful, swollen joints Antibiotics last 4 weeks? Yes No If patient seen within past 30 days: Name Purpose Patient has persistent symptoms? Yes No If Yes, was partner treated? Yes No Unknown Female Symptom History Chronic medications -

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Clinical Practice

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Constipation Ian M. Paquette, M.D. • Madhulika Varma, M.D. • Charles Ternent, M.D. Genevieve Melton-Meaux, M.D. • Janice F. Rafferty, M.D. • Daniel Feingold, M.D. Scott R. Steele, M.D. he American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons for functional constipation include at least 2 of the fol- is dedicated to assuring high-quality patient care lowing symptoms during ≥25% of defecations: straining, Tby advancing the science, prevention, and manage- lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, ment of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, relying on anus. The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee is com- manual maneuvers to promote defecation, and having less posed of Society members who are chosen because they than 3 unassisted bowel movements per week.7,8 These cri- XXX have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and teria include constipation related to the 3 common sub- rectal surgery. This committee was created to lead inter- types: colonic inertia or slow transit constipation, normal national efforts in defining quality care for conditions re- transit constipation, and pelvic floor or defecation dys- lated to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied function. However, in reality, many patients demonstrate by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the symptoms attributable to more than 1 constipation sub- best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive and type and to constipation-predominant IBS, as well. The not prescriptive. -

Celiac Disease: It's Autoimmune Not an Allergy

CELIAC DISEASE: IT’S AUTOIMMUNE NOT AN ALLERGY! Analissa Drummond PA-C Department of Pediatrics Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology HISTORY OF CELIAC DISEASE Also called gluten-sensitive enteropathy and nontropical spue First described by Dr. Samuel Gee in a 1888 report entitled “On the Coeliac Affection” Term “coeliac” derived from Greek word koiliakaos-abdominal Similar description of a chronic, malabsorptive disorder by Aretaeus from Cappadochia ( now Turkey) reaches as far back as the second century AD HISTORY CONTINUED The cause of celiac disease was unexplained until 1950 when the Dutch pediatrician Willem K Dicke recognized an association between the consumption of bread, cereals and relapsing diarrhea. This observation was corroborated when, during periods of food shortage in the Second World War, the symptoms of patients improved once bread was replaced by unconventional, non cereal containing foods. This finding confirmed the usefulness of earlier empirical diets that used pure fruit, potatoes, banana, milk, or meat. HISTORY CONTINUED After the war bread was reintroduced. Dicke and Van de Kamer began controlled experiments by exposing children with celiac disease to defined diets. They then determined fecal weight and fecal fat as a measure of malabsorption. They found that wheat, rye, barley and to a lesser degree oats, triggered malabsorption, which could be reversed after exclusion of the “toxic” cereals from the diet. Shortly after, the toxic agents were found to be present in gluten, the alcohol-soluble fraction of wheat protein. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Celiac disease is a multifactorial, autoimmune disorder that occurs in genetically susceptible individuals. Trigger is an environmental agent-gliadin component of gluten. -

بنام خدا Defecography

1/15/2019 بنام خدا Defecography 1 1/15/2019 Overview: • Definition • Anatomy • Method of assessment • Indication • Preparation • Instrument • Contrast media • Technique • Recording • Other technique • Technique pitfalls • Parameters • Abnormalities Findings Definition: Dynamic rectal examination (DRE) or defecography or proctography. • DRE provides a dynamic assessment of the act of defecation by recording the rectal expulsion of a barium paste. • DRE provides qualitative and quantitative information on the function of anorectal and pelvic floor function, and the effectiveness of the anal sphincter and rectal evacuation. 2 1/15/2019 Anatomy 3 1/15/2019 4 1/15/2019 5 1/15/2019 Method of assessment • Barium enema • Colon transit time • MR defecography Indications for dynamic rectal examination are: 1. Outlet obstruction (disorder of defecatory or rectal evacuation), caused by intussusception, enterocele or spastic pelvic floor syndrome. 2. To distinguish between anterior rectocele and enterocele. 3. Fecal incontinence combined with outlet obstruction in intra-anal intussusception. 6 1/15/2019 Preparation • No bowel preparation was used • It was deemed more physiological to observe how anorectal morphology altered during defaecation without preparation. • Two hours prior to the examination the patient ingests 135 ml of liquid barium contrast to opacify the small bowel. • In females the vagina is coated with 30 ml amidotrizoic acid 50% solution gel. • The use of tampons and gauzes soaked in barium should be avoided, because they can impaire pelvic-function. LEFT: Pathology is suspected because of a great distance between rectum and vagina. No oral contrast had been given. RIGHT: After ingestion of liquid barium contrast a large enterocele is seen. -

Adult Intussusception

1 Adult Intussusception Saulius Paskauskas and Dainius Pavalkis Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kaunas Lithuania 1. Introduction Intussusception is defined as the invagination of one segment of the gastrointestinal tract and its mesentery (intussusceptum) into the lumen of an adjacent distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract (intussuscipiens). Sliding within the bowel is propelled by intestinal peristalsis and may lead to intestinal obstruction and ischemia. Adult intussusception is a rare condition wich can occur in any site of gastrointestinal tract from stomach to rectum. It represents only about 5% of all intussusceptions (Agha, 1986) and causes 1-5% of all cases of intestinal obstructions (Begos et al., 1997; Eisen et al., 1999). Intussusception accounts for 0.003–0.02% of all hospital admissions (Weilbaecher et al., 1971). The mean age for intussusception in adults is 50 years, and and the male-to-female ratio is 1:1.3 (Rathore et. al., 2006). The child to adult ratio is more than 20:1. The condition is found in less than 1 in 1300 abdominal operations and 1 in 100 patients operated for intestinal obstruction. Intussusception in adults occurs less frequently in the colon than in the small bowel (Zubaidi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Mortality for adult intussusceptions increases from 8.7% for the benign lesions to 52.4% for the malignant variety (Azar & Berger, 1997) 2. Etiology of adult intussusception Unlike children where most cases are idiopathic, intussusception in adults has an identifiable etiology in 80- 90% of cases. The etiology of intussusception of the stomach, small bowel and the colon is quite different (Table 1). -

Constipation

Constipation Caris Diagnostics Health Improvement Series What is constipation? Constipation means that a person has three bowel movements or fewer in a week. The stool is hard and dry. Sometimes it is painful to pass. You may feel‘draggy’and full. Some people think they should have a bowel movement every day. That is not really true. There is no‘right’number of bowel movements. Each person's body finds its own normal number of bowel movements. It depends on the food you eat, how much you exercise, and other things. At one time or another, almost everyone gets constipated. In most cases, it lasts for a short time and is not serious. When you understand what causes constipation, you can take steps to prevent it. What can I do about constipation? Changing what you 4. Allow yourself enough time to have a bowel movement. eat and drink and how much you exercise will help re- Sometimes we feel so hurried that we don't pay atten- lieve and prevent constipation. Here are some steps you tion to our body's needs. Make sure you don't ignore the can take. urge to have a bowel movement. 1. Eat more fiber. Fiber helps form soft, bulky stool. It 5. Use laxatives only if a doctor says you should. is found in many vegetables, fruits, and grains. Be sure Laxatives are medicines that will make you pass a stool. to add fiber a little at a time, so your body gets used to Most people who are mildly constipated do not need it slowly. -

Uterine Prolapse Treatment Without Hysterectomy

Uterine Prolapse Treatment Without Hysterectomy Authored by Amy Rosenman, MD Can The Uterine Prolapse Be Treated Without Hysterectomy? A Resounding YES! Many gynecologists feel the best way to treat a falling uterus is to remove it, with a surgery called a hysterectomy, and then attach the apex of the vagina to healthy portions of the ligaments up inside the body. Other gynecologists, on the other hand, feel that hysterectomy is a major operation and should only be done if there is a condition of the uterus that requires it. Along those lines, there has been some debate among gynecologists regarding the need for hysterectomy to treat uterine prolapse. Some gynecologists have expressed the opinion that proper repair of the ligaments is all that is needed to correct uterine prolapse, and that the lengthier, more involved and riskier hysterectomy is not medically necessary. To that end, an operation has been recently developed that uses the laparoscope to repair those supporting ligaments and preserve the uterus. The ligaments, called the uterosacral ligaments, are most often damaged in the middle, while the lower and upper portions are usually intact. With this laparoscopic procedure, the surgeon attaches the intact lower portion of the ligaments to the strong upper portion of the ligaments with strong, permanent sutures. This accomplishes the repair without removing the uterus. This procedure requires just a short hospital stay and quick recovery. A recent study from Australia found this operation, that they named laparoscopic suture hysteropexy, has excellent results. Our practice began performing this new procedure in 2000, and our results have, likewise, been very good. -

Food and Ibd Condition Your Guide Introduction

CROHN’S & COLITIS UK SUPPORTING YOU TO MANAGE YOUR FOOD AND IBD CONDITION YOUR GUIDE INTRODUCTION ABOUT THIS BOOKLET If you have Ulcerative Colitis (UC) or Crohn’s Disease (the two main forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease - IBD) you may wonder whether food or diet plays a role in causing your illness or treating your symptoms. This booklet looks at some of the most frequently asked questions about food and IBD, and provides background information on digestion and healthy eating for people with IBD. We hope you will find it helpful. All our publications are research based and produced in consultation with patients, medical advisers and other health or associated professionals. However, they are prepared as general information and are not intended to replace specific advice from your own doctor or any other professional. Crohn’s and Colitis UK does not endorse or recommend any products mentioned. If you would like more information about the sources of evidence on which this booklet is based, or details of any conflicts of interest, or if you have any feedback on our publications, please visit our website. About Crohn’s and Colitis UK We are a national charity established in 1979. Our aim is to improve life for anyone affected by Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. We have over 28,000 members and 50 local groups throughout the UK. Membership costs from £15 per year with concessionary rates for anyone experiencing financial hardship or on a low income. This publication is available free of charge, but we © Crohn’s and Colitis UK would not be able to do this without our supporters 2015 and 2016 and members. -

Therapeutic Enema for Intussusception

Therapeutic Enema for Intussusception Therapeutic enema is used to help identify and diagnose intussusception, a serious disorder in which one part of the intestine slides into another in a telescoping manner and causes inflammation and an obstruction. Intussusception often occurs at the junction of the small and large intestine and most commonly occurs in children three to 24 months of age. A therapeutic enema using air or a contrast material solution may be performed to create pressure within the intestine and "un-telescope" the intussusception while relieving the obstruction. This exam is usually performed on an emergency basis. Tell your doctor about your child's recent illnesses, medical conditions, medications and allergies, especially to barium or iodinated contrast materials. Your child may be asked to wear a gown and remove any objects that might interfere with the x-ray images. An ultrasound may be performed to help confirm the diagnosis. What is a Therapeutic Enema for Intussusception? What is intussusception? Intussusception is a serious disorder in which one part of the intestine slides into another part of the intestine, similar to a collapsing telescope. The intestine becomes inflamed and swollen and can cause an obstruction or blockage. Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, fever, vomiting or abnormal stools. Intussusception may occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract; however, it often occurs at the junction of the small and large intestine. The condition most commonly occurs in children three months to 24 months of age. Intussusception is a medical/surgical emergency. If your child has some or all of the symptoms of intussusception, you should call your physician or an emergency medical professional immediately.