(SICCR): Management and Treatment of Complete Rectal Prolapse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Congenital Megacolon with Acute Fecal Obstruction and Diabetic Nephropathy: a Case Report

2726 EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 18: 2726-2730, 2019 Adult congenital megacolon with acute fecal obstruction and diabetic nephropathy: A case report MINGYUAN ZHANG1,2 and KEFENG DING1 1Colorectal Surgery Department, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310000; 2Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Yinzhou Peoples' Hospital, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315000, P.R. China Received November 27, 2018; Accepted June 20, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2019.7852 Abstract. Megacolon is a congenital disorder. Adult congen- sufficient amount of bowel should be removed, particularly the ital megacolon (ACM), also known as adult Hirschsprung's aganglionic segment (2). The present study reports on a case of disease, is rare and frequently manifests as constipation. ACM a 56-year-old patient with ACM, fecal impaction and diabetic is caused by the absence of ganglion cells in the submucosa nephropathy. or myenteric plexus of the bowel. Most patients undergo treat- ment of megacolon at a young age, but certain patients cannot Case report be treated until they develop bowel obstruction in adulthood. Bowel obstruction in adults always occurs in complex clinical A 56-year-old male patient with a history of chronic constipa- situations and it is frequently combined with comorbidities, tion presented to the emergency department of Yinzhou including bowel tumors, volvulus, hernias, hypertension or Peoples' Hospital (Ningbo, China) in February 2018. The diabetes mellitus. Surgical intervention is always required in patient had experienced vague abdominal distention for such cases. To avoid recurrence, a sufficient amount of bowel several days. Prior to admission, chronic bowel obstruction should be removed, particularly the aganglionic segment. -

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction Prof. Marek Jackowski Definition • Any condition interferes with normal propulsion and passage of intestinal contents. • Can involve the small bowel, colon or both small and colon as in generalized ileus. Definitions 5% of all acute surgical admissions Patients are often extremely ill requiring prompt assessment, resuscitation and intensive monitoring Obstruction a mechanical blockage arising from a structural abnormality that presents a physical barrier to the progression of gut contents. Ileus a paralytic or functional variety of obstruction Obstruction: Partial or complete Simple or strangulated Epidemiology 1 % of all hospitalization 3-5 % of emergency surgical admissions More frequent in female patients - gynecological and pelvic surgical operations are important etiologies for postop. adhesions Adhesion is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction 80% of bowel obstruction due to small bowel obstruction - the most common causes are: - Adhesion - Hernia - Neoplasm 20% due to colon obstruction - the most common cause: - CR-cancer 60-70%, - diverticular disease and volvulus - 30% Mortality rate range between 3% for simple bowel obstruction to 30% when there is strangulation or perforation Recurrent rate vary according to method of treatment ; - conservative 12% - surgical treatment 8-32% Classification • Cause of obstruction: mechanical or functional. • Duration of obstruction: acute or chronic. • Extent of obstruction: partial or complete • Type of obstruction: simple or complex (closed loop and strangulation). CLASSIFICATION DYNAMIC ADYNAMIC (MECHANICAL) (FUNCTIONAL) Peristalsis is Result from atony of working against a the intestine with loss mechanical of normal peristalsis, obstruction in the absence of a mechanical cause. or it may be present in a non-propulsive form (e.g. mesenteric vascular occlusion or pseudo-obstruction) Etiology Mechanical bowel obstruction: A. -

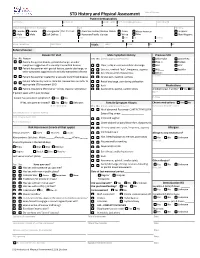

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref

STD History and Physical Assessment Date of Service: Patient Demographics Last Name First Name Middle Initial Pref. name/AKA/pronoun Date of Birth Sex (at birth) Gender (all that apply Race Ethnicity Female Female Transgender Pref. Pronoun: American Indian/Alaskan Native Asian African American Hispanic Male Male Self Define: Hawaiian/Pacific Islander White Other Non-Hispanic Street Address City State Zip County Home Telephone Cell Phone Vitals: Temp: Pulse: RR: BP: Referral Source: Reason for Visit Male Symptom History Previous STD Yes No Reason Yes No (check appropriate boxes) Chlamydia Gonorrhea Patient has genital lesions, genital discharge, or other Hep. C Herpes symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Clear, milky or mucoid urethral discharge HIV HPV Patient has partner with genital lesions, genital discharge, or Dysuria , urethral “itch”, frequency, urgency PID Syphilis other symptoms suggestive of a sexually transmitted disease Sore throat and/or hoarseness Other: Patient has partner treated for a sexually transmitted disease Scrotal pain, swelling, redness Comments: Patient referred by local or state DIS. Review labs and refer to Rectal discharge, pain during defecation appropriate STD treatment SDO Rash Medications Patient requesting STD testing – denies reasons listed above Asymmetric, painful, swollen joints Antibiotics last 4 weeks? Yes No If patient seen within past 30 days: Name Purpose Patient has persistent symptoms? Yes No If Yes, was partner treated? Yes No Unknown Female Symptom History Chronic medications -

Celiac Disease: It's Autoimmune Not an Allergy

CELIAC DISEASE: IT’S AUTOIMMUNE NOT AN ALLERGY! Analissa Drummond PA-C Department of Pediatrics Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology HISTORY OF CELIAC DISEASE Also called gluten-sensitive enteropathy and nontropical spue First described by Dr. Samuel Gee in a 1888 report entitled “On the Coeliac Affection” Term “coeliac” derived from Greek word koiliakaos-abdominal Similar description of a chronic, malabsorptive disorder by Aretaeus from Cappadochia ( now Turkey) reaches as far back as the second century AD HISTORY CONTINUED The cause of celiac disease was unexplained until 1950 when the Dutch pediatrician Willem K Dicke recognized an association between the consumption of bread, cereals and relapsing diarrhea. This observation was corroborated when, during periods of food shortage in the Second World War, the symptoms of patients improved once bread was replaced by unconventional, non cereal containing foods. This finding confirmed the usefulness of earlier empirical diets that used pure fruit, potatoes, banana, milk, or meat. HISTORY CONTINUED After the war bread was reintroduced. Dicke and Van de Kamer began controlled experiments by exposing children with celiac disease to defined diets. They then determined fecal weight and fecal fat as a measure of malabsorption. They found that wheat, rye, barley and to a lesser degree oats, triggered malabsorption, which could be reversed after exclusion of the “toxic” cereals from the diet. Shortly after, the toxic agents were found to be present in gluten, the alcohol-soluble fraction of wheat protein. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Celiac disease is a multifactorial, autoimmune disorder that occurs in genetically susceptible individuals. Trigger is an environmental agent-gliadin component of gluten. -

Adult Intussusception

1 Adult Intussusception Saulius Paskauskas and Dainius Pavalkis Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kaunas Lithuania 1. Introduction Intussusception is defined as the invagination of one segment of the gastrointestinal tract and its mesentery (intussusceptum) into the lumen of an adjacent distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract (intussuscipiens). Sliding within the bowel is propelled by intestinal peristalsis and may lead to intestinal obstruction and ischemia. Adult intussusception is a rare condition wich can occur in any site of gastrointestinal tract from stomach to rectum. It represents only about 5% of all intussusceptions (Agha, 1986) and causes 1-5% of all cases of intestinal obstructions (Begos et al., 1997; Eisen et al., 1999). Intussusception accounts for 0.003–0.02% of all hospital admissions (Weilbaecher et al., 1971). The mean age for intussusception in adults is 50 years, and and the male-to-female ratio is 1:1.3 (Rathore et. al., 2006). The child to adult ratio is more than 20:1. The condition is found in less than 1 in 1300 abdominal operations and 1 in 100 patients operated for intestinal obstruction. Intussusception in adults occurs less frequently in the colon than in the small bowel (Zubaidi et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Mortality for adult intussusceptions increases from 8.7% for the benign lesions to 52.4% for the malignant variety (Azar & Berger, 1997) 2. Etiology of adult intussusception Unlike children where most cases are idiopathic, intussusception in adults has an identifiable etiology in 80- 90% of cases. The etiology of intussusception of the stomach, small bowel and the colon is quite different (Table 1). -

Post-Operative Small Bowel Intussusception in a Pediatric Trauma Patient: a Literature Review and Unique Case Report

ACS Case Reviews in Surgery Vol. 1, No. 3 Post-Operative Small Bowel Intussusception in a Pediatric Trauma Patient: A Literature Review and Unique Case Report AUTHORS: CORRESPONDENCE AUTHOR:* AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS: Walsh NJa, Dadzie KAb, Jones AJb, Hatley RMa.c Andrew J. Jones, MD a Department of Surgery, Augusta University 1120 15th St, BI-4070 Health, Augusta, GA, USA Augusta, GA, 30912 b Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, [email protected] Augusta, GA, USA (770) 827-8816 c Section of Pediatric Surgery, Augusta University Health, Augusta, GA, USA Background Intussusception is a well-documented cause of acute abdomen in the pediatric population; however, post-traumatic and post-operative intussusceptions are exceptionally uncommon. Summary An otherwise healthy eight-year-old girl presented as a level II trauma via EMS following a motor vehicle accident (MVA). The patient complained of diffuse abdominal pain and back pain on arrival. Physical exam was remarkable for tachycardia, right coastal margin tenderness to palpation, non-labored breathing, diffuse abdominal tenderness and a seatbelt sign. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was suspicious for duodenal and/or mesenteric injury, warranting an exploratory laparotomy. After this initial operation, she later presented with symptoms of small bowel obstruction. Repeat CT of the abdomen obtained on post-operative day 14 showed dilated loops of distant small bowel, air fluid levels and a swirled appearance of the mesentery, concerning for a closed loop obstruction. She was taken back to the operating room and intra-operative findings revealed a feathery adhesion of the small bowel to the transverse colon with no dilation of the proximal small bowel and a distal jejunojejunal intussusception. -

Coeliac Disease: the Histology Report

Digestive and Liver Disease 43S (2011) S385–S395 Coeliac disease: The histology report Vincenzo Villanacci a,*, Paola Ceppa b, Enrico Tavani c, Carla Vindigni d, Umberto Volta e On behalf of the “Gruppo Italiano Patologi Apparato Digerente (GIPAD)” and of the “Società Italiana di Anatomia Patologica e Citopatologia Diagnostica”/International Academy of Pathology, Italian division (SIAPEC/IAP) aDepartment of Pathology, Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy bSurgical Department, Integrated Morphological and Methods Section of Pathological Anatomy, University of Genova, Genova, Italy cDepartment of Pathology, G. Salvini Hospital Rho, Rho, Italy dDepartment of Pathology and Human Oncology, University of Siena, Siena, Italy eDepartment of Diseases of the Digestive System and Internal Medicine, Policlinico S. Orsola – Malpighi, Bologna, Bologna, Italy Abstract To this day intestinal biopsy is justly considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of coeliac disease (CD). The aim of the authors in setting up these guidelines was to assist pathologists in formulating a more precise morphological evaluation of a duodenal biopsy in the light of clinical and laboratory data, to prepare histological samples with correctly oriented biopsies and in the differential diagnosis with other pathological entities and complications of the disease. A further intention was to promote the conviction for the need of a close collaborative relationship between different specialists namely the concept of a “multidisciplinary team”. © 2011 Editrice Gastroenterologica Italiana S.r.l. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Coeliac disease; GIPAD report; T lymphocytes; Malabsorption 1. Introduction based on the most recent acquisitions regarding the diagnosis and pathogenesis of coeliac disease, is the only specialist that These guidelines are intended as an aid for pathologists, can make the final diagnosis of coeliac disease. -

Loop Formation of Meckel's Diverticulum Causing

Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2011;17 (6):567-569 Case Report Olgu Sunumu doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2011.54533 Loop formation of Meckel’s diverticulum causing small bowel obstruction in adults: report of two cases Erişkinlerde ince bağırsak tıkanıklığına neden olan Meckel divertikülüne bağlı halka oluşumu: İki olgu sunumu Shilpi SINGH GUPTA, Onkar SINGH Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital anom- Meckel divertikülü olguların çoğunluğunda asemptomatik aly of the gastrointestinal tract, and in the majority of cases olarak kalan en yaygın konjenital gastrointestinal sistem it remains asymptomatic. The total lifetime rate of complica- anomalisidir. Yaşam boyu komplikasyon oranı %4’dür. tions is 4%. It is an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction Erişkinlerde nadir bir intestinal tıkanıklık nedenidir. İnce in adults. Loop formation of Meckel’s diverticulum leading bağırsak tıkanıklığına neden olan Meckel divertikülüne to small bowel obstruction is an extremely rare event. We ilişkin halka oluşumu oldukça enderdir. Biz, Meckel di- report two such cases in which the bowel became obstructed vertikülünün distal ucu ile proksimal ileum ve mezenter and strangulated in a loop formed by adhesion of the distal arasında halka şeklinde adezyonlar oluşmasıyla bağırsa- end of the Meckel’s diverticulum to the proximal ileum and ğın tıkandığı ve strangülasyona uğradığı iki olguyu sunu- mesentery. yoruz. Key Words: Adults; intestinal obstruction; Meckel’s diverticu- Anahtar Sözcükler: Erişkinler; intestinal tıkanıklık; Meckel diver- lum. tikülü. Meckel’s diverticulum is an uncommon cause of rigidity throughout. Bowel sounds were increased. intestinal obstruction in adult life.[1] Rarely, Meckel’s Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen revealed hy- diverticulum may form a loop due to adhesions be- perperistaltic dilated small bowel loops. -

Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 64 / No. 3 June 5, 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Gonococcal Infections ...................................................................................... 60 Methods ....................................................................................................................1 Diseases Characterized by Vaginal Discharge .......................................... 69 Clinical Prevention Guidance ............................................................................2 Bacterial Vaginosis .......................................................................................... 69 Special Populations ..............................................................................................9 Trichomoniasis ................................................................................................. 72 Emerging Issues .................................................................................................. 17 Vulvovaginal Candidiasis ............................................................................. 75 Hepatitis C ......................................................................................................... 17 Pelvic Inflammatory -

ESMO Colorectal Cancer Guide for Patients English

Colorectal Cancer What is colorectal cancer? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines COLORECTAL CANCER: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of colorectal cancer and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of colorectal cancer. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of colorectal cancer. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the leading author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals. It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Colorectal Cancer: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines - v.2016.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

A Case of Solitary Rectal Diverticulum Presenting with a Large Retrorectal Abscess T

Annals of Medicine and Surgery 49 (2020) 57–60 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Annals of Medicine and Surgery journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/amsu Case report A case of solitary rectal diverticulum presenting with a large retrorectal abscess T ∗ Stefanos Gorgoraptisa,Sofia Xenakia, ,1, Elias Athanasakisa, Anna Daskalakia, Konstantinos Lasithiotakisa, Evangelia Chrysoub, Emmanuel Chrysosa a Department of General Surgery, University Hospital of Heraklion Crete, Greece b Department of Radiology, University Hospital of Heraklion Crete, Greece ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Colonic diverticular disease is a common condition, affecting 50% of the population aged above 80. In contrast, Rectal diverticulum rectal diverticular disease is a rare condition with very few cases reported, while symptomatic rectal diverticular Abscess disease is even rarer. We present a case of a symptomatic large rectal diverticulum presenting with a retrorectal Diverticulitis abscess. A 49-year-old Caucasian female was brought to the emergency department complaining of abdominal Complications pain and weakness in the lower limbs. She was found to have obstructive uropathy and unilateral sciatic neu- ropathy. She rapidly developed acute abdomen and emergency laparotomy revealed a giant purulent rectal diverticulum. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and a loop colostomy was made to decompress the colon. 1. Introduction Neurologic examination revealed asymmetric paraparesis and hy- poesthesia in the lower limbs, affecting hip extension, knee flexion, Despite the high incidence of colonic diverticular disease, the oc- ankle dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, eversion and big toe extension, with currence of rectal diverticula is extremely unusual, with only few, brisk tendon reflexes in the knees but absent in the ankle, in keeping sporadic published reports since 1911 [11]. -

Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya

Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya Table of Contents Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Conditions in Kenya..................................1 FOREWORD..........................................................................................................................................3 PREFACE...............................................................................................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................................................5 1. ACUTE INJURIES AND TRAUMA & SELECTED EMERGENCIES..................................................7 1.1. Anaphylaxis & Cardiac Arrest...................................................................................................7 1.2. Abdominal Trauma....................................................................................................................8 1.3. Bites & Rabies.........................................................................................................................10 1.4. Burns.......................................................................................................................................13 1.5. Disaster Plan...........................................................................................................................16