Over 50 Years in Computing: Memoirs of Raymond E. Miller Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript of 790112 Hearing in Avila

MUCH.EAR REGULAT0RY COMMjSS10N 1N THE NATTER OF.. PACXPZC 'GAS 5 KLECYRXC, @~=~A."tZ (09.ah2.o Canyon Unit:s 2. @md 2) C4~'.ref Mog 50 275 50-323 Av9.1a Beach, Ca2.if'araia P/ace- 12 Zanuaxy 3.979 8S45 -87's Date- Pages Telephone: (202) ~&7.3700 ACE'- FEDEBALREPOBTEBS, INC. zBMRR 603 / Officisl0 epertere 444 North Capital Street Washington, D.C. 20001 P NAT1ONWlDE t QVPRAG"-" - DAlLY 4: "ti .d3.GCIQ $PJX LEQ st'Z Q Qp L%21EBXCZi QELCH i'i c:LBQCQD Zi7C&~iLZ~ 8 . QULRPORZ COPE'IXSSZOi'. »»»»&»~»~»»»»»» Xn the ma"h~-; of: Qh PBCXPXC GAS E«ELZCTRXC COK?2ZY Doclc8t. LioG ~ 50 275 Si3»323 {99.K~33.0 CaIlj«cn UILi~cs 1 RnQ 2) »» I»»»»w»»»»»»»»»»»»A W»»»041»»4!l»»+ Clwv&1 l GZ RCl>~l g r, ~+ BGil «+4Yli8 '«~P XLITIg h SKVi1Q Bek~Chg CQ1".foh'~liibo PZ''i QQ'i~ 3 2 JQ'iQ~ J 1979 T59 18cYzinLJ iIL "i QQ c~+QvQ»8Q'~it,'GQ I;-~zP~~P. "ERG zeconvene6, gursvan to aa~ouz.~anal", at, 9:30 ".rl. SWORE ELX>~FTH BGh" BS ~ Chaizm~~a~ McL?9.c 84CpCrg GiDQ X>9.cc'QQ9.ng BQ "mQ DR. VTZL~IM4 E. SKHTXH, kf~ebar. GL-rrrZ O. mXGHr., r~~e=-. >i -PEKtQKCPS h OII b85M1f Of APP13.CRIIt. PGCi Pic QBG 5 H18CM2. ~ CCRPB'QP ' BE7CE @%TON F«I~) ~ 3210) Mo rZIlg.~~q M PhaeniX, 2-i"OIla 8S02.2 mu:oxen .H. zUaaUSH, HBQO akim PBXXI*P CKlHZp ~BC/lb Lec~Q1 08QcL~SQ p Pacific Gas F "1ec+-ic I Hc~l" Ith, CQGlpanp'g 77 BQ«L1o BMOCp Pz«iElcisco g Cafe.fo~ia 943.06 ;4 )I '> 1 $ 1 ~ 5 il1 ~ i ~ I h ~ ti RPPElu~CCES: (Cant'cO On behalf of. -

Challenges in Generating the Next Computer Generation

2. Challenges in Generating the Next Computer Generation GORDON BELL A leading designer of computer structures traces the evolution of past and present generations of computers and speculates about possiblefuture courses of develop- ment for the next generations. WHENthe Japanese told us about the Fifth Generation, we knew we were in a race. Ed Feigenbaum and Pamela McCor- duck characterized it in their book, The Fifth Generation, but did not chart the racetrack. In the 1970~~while writing Com- puter Structures with Allen Newell, and recently in orga- nizing the collection of The Computer Museum, I identified the pattern repeated by each generation. In order to win, or even to be in the race, knowing the course is essential. The Cycle of Generations A computer generation is produced when a specific cycle of events occurs. The cycle proceeds when motivation (e.g. the threat of industrial annihilation) frees resources; CHALLENGES IN GENERATING THE NEXT COMPUTER GENERATION 27 techno log^ and science provide ideas for building with both industry and academe providing the push. new mach'ines; The Japanese Approach to the Next Generation organizations arise to build the new computing structures; and (after the fad) "If a computer understands English, it must be Japanese."(A pearl from Alan Perlis, speaking at The Computer Museum, use of the resulting products confirm a generation's September 1983) existence. The Japanese Fifth Generation plan, formulated in 1980, A generation results from at least two trips around this is based on worldwide research. Because the Japanese cycle, each succeeding trip an accelerated version of the pre- understand large-scale, long-term interactive processes, vious one, as in a cyclotron. -

History in the Computing Curriculum 1950 to 1959

History in the Computing Curriculum Appendix A4 1950 to 1959 1950 [early]: Project Whirlwind becomes operational on a limited basis. (w) 1950 [February]: Remington-Rand Corporation acquires the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation. The latter loses crucial contracts due to the McCarthy trials. (a,e,w) 1950 [April]: The SEAC becomes operational at the National Bureau of Standards. (w) 1950 [May]: The Pilot ACE is completed at England's National Physics Laboratory and runs its first program on May 10. (e,w) 1950 [July]: The Standards Western Automatic Computer (SWAC) becomes operational. (w) 1950: The SWAC, built under Harry Huskey's leadership, is dedicated at UCLA on August 17. (e) 1950: Alan Turing publishes an article in the journal Mind establishing the criteria for the Turing Test of machine intelligence. (e) 1950 [November]: The Bell Labs Model VI computer becomes operational. 1950: Konrad Zuse installs the refurbished Z4 computer at the ETH in Zurich. (w) 1951 [February]: The first Ferranti Mark I version of the Manchester University machine is delivered to Manchester University. (w) 1951 [March]: The first UNIVAC I computer is delivered to the US Census Bureau on March 31. It weighed 16,000 pounds, contained 5,000 vacuum tubes, could do 1000 calculations per second, and costs $159,000. (a,e,w) 1951: The US Census Bureau buys a second UNIVAC I. (p) 1951 [May]: Jay Forrester files a patent application for the matrix core memory on May 11. (e) 1951 [June]: The first programming error at the Census Bureau occurs on June 16. (a) 1951 [July]: The IAS machine is in limited operation. -

Cosmograph? What's A

Volunteer Information Exchange Sharing what we know with those we know Volume 2 Number 16 November 23, 2012 CHM's New Blog Contribute To The VIE Recent CHM Blog Entries Thanks to Doris Duncan and Lyle Bickley for their Kirsten Tashev keeps us up-to-date on our new CHM articles this month. What an amazing set of people Blog. Recent Entries are: are our volunteers. • 10/19 - Alex Lux “Little Green Men,” I had an opportunity to visit the IBM archives in New http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/little-green- York last month. It was occasioned by by question, men/ “What is a cosmograph?” See the article on page 2. • 10/24 - Dag Spicer A special visitor to CHM There will be more on “What I did on my vacation” in and his work on Squee: the Robot Squirrel! future issues. http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/squee-the- So, if you do anything that relates to the CHM while robot-squirrel/ you are on vacation, please remember the VIE. We • 10/26 - Karen Kroslowitz, need your stories to make the VIE vibrant. http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/preservation- conservation-restoration-whats-the-difference/ Please share your knowledge with your colleagues. Contribute to the VIE. • 10/31 - Chris Garcia http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/the-haunted- Jim Strickland [email protected] house/ • 11/2 - William Harnack about his trip to Blizzard Entertainment for the new Make Software exhibit in development, The VIE Cumulative Index is stored at: http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/my-gamer- http://s3data.computerhistory.org.s3.amazo soul-wept-with-epic-joy/ naws.com/chmedu/VIE- • 11/4 Marc Weber on his amazing trip to Kenya to 000_Cumulative_Topic_Index.pdf conduct research for the upcoming Make Software: Change the World! exhibit, http://www.computerhistory.org/atchm/the-other- internet-part-1-masai-mara/ • 11/15 Alex Lux i n honor of Guinness World Record Day Nov. -

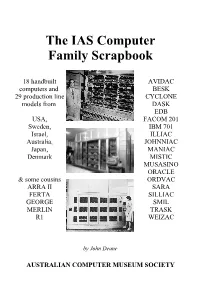

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook 18 handbuilt AVIDAC computers and BESK 29 production line CYCLONE models from DASK EDB USA, FACOM 201 Sweden, IBM 701 Israel, ILLIAC Australia, JOHNNIAC Japan, MANIAC Denmark MISTIC MUSASINO ORACLE & some cousins ORDVAC ARRA II SARA FERTA SILLIAC GEORGE SMIL MERLIN TRASK R1 WEIZAC by John Deane AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER MUSEUM SOCIETY The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook by John Deane Front cover: John von Neumann and the IAS Computer (Photo by Alan Richards, courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Rand's JOHNNIAC (Rand Corp photo), University of Sydney's SILLIAC (photo courtesy of the University of Sydney Science Foundation for Physics). Back cover: Lawrence Von Tersch surrounded by parts of Michigan State University's MISTIC (photo courtesy of Michigan State University). The “IAS Family” is more formally known as Princeton Class machines (the Institute for Advanced Study is at Princeton, NJ, USA), and they were referred to as JONIACs by Klara von Neumann in her forward to her husband's book The Computer and the Brain. Photograph copyright generally belongs to the institution that built the machine. Text © 2003 John Deane [email protected] Published by the Australian Computer Museum Society Inc PO Box 847, Pennant Hills NSW 2120, Australia Acknowledgments My thanks to Simon Lavington & J.A.N. Lee for your encouragement. A great many people responded to my questions about their machines while I was working on a history of SILLIAC. I have been sent manuals, newsletters, web references, photos, -

An Introduction to the Illiac Iv System

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 510.84 I£63c no.1-10 j s U~&Pi$F ^T®&/;r£ AUG 51976 The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN ^ j»s» r?* $»» 1 ft «£ 8 ! I tn jul ovFFcn m ° 4 ^ L161 — O-1096 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/introductiontoilOOdene . Engirt HNGINEER/NG LISRABV UN ' VE f S°"' INFERENCE ROD X° ,ced Computation UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAK URBANA, ILLINOIS 61801 CAC Document No. 10 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ILLIAC D7 SYSTEM by Stewart A. Denenberg July 15, 1971 (revised November 1, 1972) CAC Document No. 10 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ILLIAC IV SYSTEM by Stewart A. Denenberg Center for Advanced Computation University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign Urban a, Illinois 6l801 ILLIAC IV Document No. 225 Department of Computer Science File No. 850 July 15, 1971 (revised November 1, 1972) This work was supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, as implemented initially by the Rome Air Development Center, Research and Technology Division, Air Force Systems Command, Griffiss Air Force Base, New York under Contract No. USAF 30(602)-klkk, and beginning January 17, 1972, by the NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. To Claire " HB How to Read this Book This book was written for an applications programmer who would like a tutorial description of the ILLIAC IV System before attempting to read the reference manual. -

Anna/S of the History of Computing, Volume 13, 1991, Author, Title, and Subject Index

Anna/s of the History of Computing, Volume 13, 1991, Author, Title, and Subject Index 1880 Census, 247 Analytical Engine, 123,125, 131, 137, 141, 144, Barlow, Hugh, 97 1890 Census, 64,251 147,295 Barth, Theodore Harold, 166 425 Park Avenue, 104 AND, 359 BASIC, 3843 45-column punched-card, 263 ANelex, 67,70 Basic Software Development Division, 24 590 Madison Avenue, 102 Antoine, Jacques, 342 Bauer, Friedrich L., 93,94,356 80-column punched card, 257 AP-101,352 BBN Advanced Computers, 191 APL, 36 BBN time-sharing system, 274 A APL\360,38 Beginning of Informatics, 344 A History of Medical Informatics (rev.), 311 Apple, 203 Bell Labs relay computers, 81 A World Ruled By Number (rev.), 313 APPLE II, 234 Bemer, Robert W., 5,101,369 A.M. Turing Award, 275 Apple LaserWriter (fig.), 216 Benchmarks, 198 A.B. Dick Company, 63,73,207,208 Apple Macintosh, 369 Bendix (later CDC) G-20,359 A.B. Dick Model 910 Address Printer (fig.), 74 Appleyard, Rollo, 156 Bendix G15,302 A.B. Dick Videograph, 72 APT, 36,38,43,44 Bennett, William, 355 A.B. Dick Videojet 9600 (fig.), 74 APT II, 44 Bernstein, Alex, 103 ABC, 1,118 Archives of Data-Processing History (rev.), 310 Bertho-Lavenir, Catherine, 357 Aberdeen Proving Ground, 325 Argonne National Laboratory, 325 BESM-6,181 Accad, Yigal, 329 Armand, Louis, 344 Bessel functions, 327 Accumulator Plate Statistics, 1913,256 Armand, Richard (au.), 315,341 BETA, 63,69 ACE, 120 Armand, Richard (fig.), 342 Bicentenary of the Death of Thomas Fuller ACE computer, 297 Armer, Paul, 231 (rev.), 117 ACM, 1,100,355,362 Armv Map Service, -

GUIDE to the G.R. BROOKS ARCHIVE in the POWERHOUSE MUSEUM Helen Yoxall 1998

GUIDE TO THE G.R. BROOKS ARCHIVE IN THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM Helen Yoxall 1998 CONTENTS Biographical Note Series List Series Descriptions and Item Lists COLLECTED ARCHIVES BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Registration Number: 97/203/1 Creator: Brooks, George Roderick Born on 19 June 1917, George Roderick Brooks is an engineer who worked on the design, construction and implementation of first generation computer technology at the Adolph Basser Computer Laboratory, School of Physics, University of Sydney during the 1950s-60s. He now (1997) lives at Leura, New South Wales. Explanatory note re SILLIAC computer SILLIAC was the second stored program electronic computer to be built in Australia and one of the earliest in the world. The SILLIAC computer is one of a family of machines sharing the same principles of system design, of logical interconnections and of circuit design. These were formulated by the staff of the Electronic Computer Project at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. The system design was based on a specification issued by Burles, Goldstine and von Neumann in 1946 whilst the principles guiding the internal design of circuits & logical nets were the responsibility of J.H. Bigelow. The first working machine of the Princeton type was completed by the staff of the Engineering Research Laboratory at the University of Illinois in November 1951. This was the ORDVAC computer, a machine ordered by the Ordnance Department for the Ballistic Research Laboratories of Aberdeen Proving Ground. The terms of the contract required that the machine be supplied complete with drawings, programs and handbooks and permitted the construction of a duplicate machine to become the property of the University. -

Sept. 1St Led by Ralph Meagher and Rabin Abraham H

Neumann architecture [June 10] Michael Oser machine, developed in a project Sept. 1st led by Ralph Meagher and Rabin Abraham H. Taub who had both Born: Sept. 1, 1931; worked with von Neumann at William Stanley Breslau, Germany IAS. Jevons Rabin and Dana Scott [Oct 11] It used 2,800 vacuum tubes, authored the 1959 paper “Finite measured 10 ft. by 2 ft. by 8.5 ft., Born: Sept. 1, 1835; Automata and their Decision and weighed 4,000 pounds. It Liverpool, UK Problems” which introduced the employed an early form of hexadecimal notation where the Died: Aug. 13, 1882 idea of nondeterministic machines, which has proved to letters K, S, N, J, F, and L stood Jevons was best known as an be enormously valuable in for 10 to 15. Programmers used economist, and in particular for computing theory. to remember them with the his theory linking sunspots and catchphrase “King Sized economics cycles. However, he A second groundbreaking paper, Numbers Just For Laughs.” also wrote a popular textbook “Degree of Difficulty of on logic, and created the logic Computing a Function and a The ILLIAC I could perform piano (aka logical abacus) Partial Ordering of Recursive 11,000 operations per second. utilizing Boolean logic [Nov 2]. Sets” (1960), grew out of a ILLIAC II, a transistor-and-diode He had a clockmaker construct a puzzle that John McCarthy [Sept machine completed in 1963, working version for him in 1869. 4] posed about spies, guards, could perform 500,000 and passwords: operations per second. The ILLIAC III was a special-purpose "The spies have passwords that computer designed for the allow them to pass from enemy automatic scanning of large territory to their own. -

John Von Neumann in Computer Science

John von Neumann in Computer Science Balint Domolki Honorary President of the John von Neumann Computer Society The 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Panel dedicated to John von Neumann “a Pioneer of Modern Computer Science” SMC 2016 1 John von Neumann (1903-1957) SMC 2016 2 Three periods I. Study (1903-26) Marina von Neumann.Whitman: Budapest, Berlin, Zurich "...my father led a double life: as II. „Ivory tower” (1927-38) a commanding figure in the ivory tower of pure science, and as a Berlin, Hamburg, Gottingen man of action, in constant Princeton demand as an advisor, consultant and decision-maker in the long III. „Man of action” (1939-57) struggle to insure that the United Princeton, Los Alamos, …. States would be triumphant in both the hot and the cold wars Washington that together dominated the half century from 1939 until 1989." SMC 2016 3 I. Study • Rich banker family, received nobility patent in 1913 („von…”) • Early talent (not only in math) • „Fasor” Lutheran Gymnasium (also: Wigner, Harsanyi) • Excellent math. teacher: Laszlo Ratz (award for secondary school teachers!) • Tutoring by TU professors • Publication at age of 19, together with Prof. Fekete • Studying chemistry in Berlin, Zurich, plus mathematics in Budapest SMC 2016 4 II: „Ivory tower” • Teaching at Univ. Berlin (1926-28) and Hamburg (1929-30) IAS • Fellowship to Gottingen, meeting Hilbert, Heisenberg • Leaving for US in 1930: Princeton Univ. • „Founding member” of the Institute for Advanced Studies (IAS), together with Einstein and Gödel • Leading US mathematician with high international reputation, member of US National Academy. -

William Kahan)

An interview with C. W. “BILL” GEAR Conducted by Thomas Haigh On September 17-19, 2005 In Princeton, New Jersey Interview conducted by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, as part of grant # DE-FG02-01ER25547 awarded by the US Department of Energy. Transcript and original tapes donated to the Computer History Museum by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics © Computer History Museum Mountain View, California ABSTRACT Numerical analyst Bill Gear discusses his entire career to date. Born in London in 1935, Gear studied mathematics at Peterhouse, Cambridge before winning a fellowship for graduate study in America. He received a Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign in 1960, under the direction of Abraham Taub. During this time Gear worked in the Digital Computer Laboratory, collaborating with Don Gillies on the design of ILLIAC II. He discusses in detail the operation of ILLIAC, its applications, and the work of the lab (including his relationships with fellow graduate student Gene Golub and visitor William Kahan). On graduation, Gear returned to England for two years, where he worked at IBM’s laboratory in Hurlsley on computer architecture projects, serving as a representative to the SPREAD committee charged with devising what became the System 360 architecture. Gear then returned to Urbana-Champaign, where he remained until 1990, serving as a professor of computer science and applied mathematics and, from 1985 onward, as head of the computer science department. He supervised twenty two Ph.D. students, including Linda Petzold. Gear is best known for his work on the solution of stiff ordinary differential equations, and he discusses the origins of his interests in this area, the creation of his DIFSUB routine, and the impact of his book “Numerical Initial Value Problems in Ordinary Differential Equations” (1971). -

Computing Reflections a Personal History View

Computing Reflections a personal history view Arthur C. Fleck Computing Reflections a personal history view Arthur C. Fleck Professor Emeritus University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa April 2018 Contents Acknowledgements iii Preface iv About the Author vi Chapter I: My Initiation into Computing 1 A Serendipitous Choice 1 Getting Serious 3 Chapter II: A History of Automaton Automorphisms 8 The Excitement of New Ideas 8 Basic Definitions 13 Initial Results 16 Ensuing Developments 23 Final Remarks on Automorphisms 28 Chapter III: Programming Languages Thru the Years 30 Linguistic Structure for Computer Programs 30 Settling into an Academic Career 36 Programming Language Proliferation 40 Advancing the Theory of Programming Languages 44 Evolution of Types and Control Structures 48 Distinctive Language Alternatives 51 Declarative Languages 60 Summary and Conclusions 68 Bibliography 71 ii Acknowledgements Special thanks to Edgar Daylight for his early encouragement to pursue this writing as without that it would not have come to fruition. I am grateful for the careful reading and helpful suggestions provided by Sungwan Kang on earlier versions. iii Preface This treatise sets forth notes and personal impressions on computing from throughout my career. While pursuing my education, there were no computer science departments, and academic opportunities in computing were rare. I indicate the path I followed and how it led me in a seemingly preordained way to a career in computing education. My career involved both research and teaching, and efforts on both fronts are discussed in the following. I always found a natural attraction for more formal aspects of computing. Initially this was in conceptual models of computing and the universal conclusions they lead to.