The First Computers—History and Architectures, Edited by Raúl Rojas and Ulf Hashagen, 2000 the First Computers—History and Architectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology? Hayley A. LeBlanc Sunset High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y LeBlanc, Hayley A., "To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. To what extent did British advancements in cryptanalysis during World War 2 influence the development of computer technology? Hayley LeBlanc 1936 words 1 Table of Contents Section A: Plan of Investigation…………………………………………………………………..3 Section B: Summary of Evidence………………………………………………………………....4 Section C: Evaluation of Sources…………………………………………………………………6 Section D: Analysis………………………………………………………………………………..7 Section E: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………10 Section F: List of Sources………………………………………………………………………..11 Appendix A: Explanation of the Enigma Machine……………………………………….……...13 Appendix B: Glossary of Cryptology Terms.…………………………………………………....16 2 Section A: Plan of Investigation This investigation will focus on the advancements made in the field of computing by British codebreakers working on German ciphers during World War 2 (19391945). -

1 Oral History Interview with Brian Randell January 7, 2021 Via Zoom

Oral History Interview with Brian Randell January 7, 2021 Via Zoom Conducted by William Aspray Charles Babbage Institute 1 Abstract Brian Randell tells about his upbringing and his work at English Electric, IBM, and Newcastle University. The primary topic of the interview is his work in the history of computing. He discusses his discovery of the Irish computer pioneer Percy Ludgate, the preparation of his edited volume The Origins of Digital Computers, various lectures he has given on the history of computing, his PhD supervision of Martin Campbell-Kelly, the Computer History Museum, his contribution to the second edition of A Computer Perspective, and his involvement in making public the World War 2 Bletchley Park Colossus code- breaking machines, among other topics. This interview is part of a series of interviews on the early history of the history of computing. Keywords: English Electric, IBM, Newcastle University, Bletchley Park, Martin Campbell-Kelly, Computer History Museum, Jim Horning, Gwen Bell, Gordon Bell, Enigma machine, Curta (calculating device), Charles and Ray Eames, I. Bernard Cohen, Charles Babbage, Percy Ludgate. 2 Aspray: This is an interview on the 7th of January 2021 with Brian Randell. The interviewer is William Aspray. We’re doing this interview via Zoom. Brian, could you briefly talk about when and where you were born, a little bit about your growing up and your interests during that time, all the way through your formal education? Randell: Ok. I was born in 1936 in Cardiff, Wales. Went to school, high school, there. In retrospect, one of the things I missed out then was learning or being taught Welsh. -

COM 113 INTRO to COMPUTER PROGRAMMING Theory Book

1 [Type the document title] UNESCO -NIGERIA TECHNICAL & VOCATIONAL EDUCATION REVITALISATION PROJECT -PHASE II NATIONAL DIPLOMA IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY Computer Programming COURSE CODE: COM113 YEAR I - SE MESTER I THEORY Version 1: December 2008 2 [Type the document title] Table of Contents WEEK 1 Concept of programming ................................................................................................................ 6 Features of a good computer program ............................................................................................ 7 System Development Cycle ............................................................................................................ 9 WEEK 2 Concept of Algorithm ................................................................................................................... 11 Features of an Algorithm .............................................................................................................. 11 Methods of Representing Algorithm ............................................................................................ 11 Pseudo code .................................................................................................................................. 12 WEEK 3 English-like form .......................................................................................................................... 15 Flowchart ..................................................................................................................................... -

United States of America Assassination

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD *** PUBLIC HEARING Federal Building 1100 Commerce Room 7A23 Dallas, Texas Friday, November 18, 1994 The above-entitled proceedings commenced, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m., John R. Tunheim, chairman, presiding. PRESENT FOR ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD: JOHN R. TUNHEIM, Chairman HENRY F. GRAFF, Member KERMIT L. HALL, Member WILLIAM L. JOYCE, Member ANNA K. NELSON, Member DAVID G. MARWELL, Executive Director WITNESSES: JIM MARRS DAVID J. MURRAH ADELE E.U. EDISEN GARY MACK ROBERT VERNON THOMAS WILSON WALLACE MILAM BEVERLY OLIVER MASSEGEE STEVE OSBORN PHILIP TenBRINK JOHN McLAUGHLIN GARY L. AGUILAR HAL VERB THOMAS MEROS LAWRENCE SUTHERLAND JOSEPH BACKES MARTIN SHACKELFORD ROY SCHAEFFER 2 KENNETH SMITH 3 P R O C E E D I N G S [10:05 a.m.] CHAIRMAN TUNHEIM: Good morning everyone, and welcome everyone to this public hearing held today in Dallas by the Assassination Records Review Board. The Review Board is an independent Federal agency that was established by Congress for a very important purpose, to identify and secure all the materials and documentation regarding the assassination of President John Kennedy and its aftermath. The purpose is to provide to the American public a complete record of this national tragedy, a record that is fully accessible to anyone who wishes to go see it. The members of the Review Board, which is a part-time citizen panel, were nominated by President Clinton and confirmed by the United States Senate. I am John Tunheim, Chair of the Board, I am also the Chief Deputy Attorney General from Minnesota. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CURVE/open How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2014, 'How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bombe: Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park' History of Science, vol 52, no. 2, pp. 200-222 https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0073275314529861 DOI 10.1177/0073275314529861 ISSN 0073-2753 ESSN 1753-8564 Publisher: Sage Publications Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Mechanising the Information War – Machine Research and Development and Bletchley Park Christopher Smith Abstract The Bombe machine was a key device in the cryptanalysis of the ciphers created by the machine system widely employed by the Axis powers during the Second World War – Enigma. -

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

Information Technology 3 and 4/1998. Emerging

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] EMERGING TECHNOLOGY SERIES 3 and 4/1998 Information Technology UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna, 2000 EMERGING TO OUR READERS TECHNOLOGY SERIES Of special interest in this issue of Emerging Technology Series: Information T~chn~~ogy is the focus on a meeting that took INFORMATION place from 2n to 4 November 1998, in Bangalore, India. -

Table of Contents

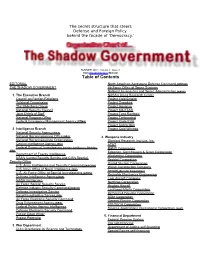

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases

Michigan Law Review Volume 91 Issue 3 1992 Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases John W.L. Ogilive University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ogilive, Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases, 91 MICH. L. REV. 526 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol91/iss3/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases John W.L. Ogilvie INTRODUCTION Although computer programs enjoy copyright protection as pro tectable "literary works" under the federal copyright statute, 1 the case law governing software infringement is confused, inconsistent, and even unintelligible to those who must interpret it.2 A computer pro gram is often viewed as a collection of different parts, just as a book or play is seen as an amalgamation of plot, characters, and other familiar parts. However, different courts recognize vastly different computer program parts for copyright infringement purposes. 3 Much of the dis array in software copyright law stems from mutually incompatible and conclusory program part definitions that bear no relation to how a computer program is actually designed and created. -

Working on ENIAC: the Lost Labors of the Information Age

Working on ENIAC: The Lost Labors of the Information Age Thomas Haigh www.tomandmaria.com/tom University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee & Mark Priestley www.MarkPriestley.net This Research Is Sponsored By • Mrs L.D. Rope’s Second Charitable Trust • Mrs L.D. Rope’s Third Charitable Trust Thanks for contributions by my coauthors Mark Priestley & Crispin Rope. And to assistance from others including Ann Graf, Peter Sachs Collopy, and Stephanie Dick. www.EniacInAction.com CONVENTIONAL HISTORY OF COMPUTING www.EniacInAction.com The Battle for “Firsts” www.EniacInAction.com Example: Alan Turing • A lone genius, according to The Imitation Game – “I don’t have time to explain myself as I go along, and I’m afraid these men will only slow me down” • Hand building “Christopher” – In reality hundreds of “bombes” manufactured www.EniacInAction.com Isaacson’s “The Innovators” • Many admirable features – Stress on teamwork – Lively writing – References to scholarly history – Goes back beyond 1970s – Stresses role of liberal arts in tech innovation • But going to disagree with some basic assumptions – Like the subtitle! www.EniacInAction.com Amazon • Isaacson has 7 of the top 10 in “Computer Industry History” – 4 Jobs – 3 Innovators www.EniacInAction.com Groundbreaking for “Pennovation Center” Oct, 2014 “Six women Ph.D. students were tasked with programming the machine, but when the computer was unveiled to the public on Valentine’s Day of 1946, Isaacson said, the women programmers were not invited to the black tie event after the announcement.” www.EniacInAction.com Teams of Superheroes www.EniacInAction.com ENIAC as one of the “Great Machines” www.EniacInAction.com ENIAC Life Story • 1943: Proposed and approved. -

The Roots of Software Engineering*

THE ROOTS OF SOFTWARE ENGINEERING* Michael S. Mahoney Princeton University (CWI Quarterly 3,4(1990), 325-334) At the International Conference on the History of Computing held in Los Alamos in 1976, R.W. Hamming placed his proposed agenda in the title of his paper: "We Would Know What They Thought When They Did It."1 He pleaded for a history of computing that pursued the contextual development of ideas, rather than merely listing names, dates, and places of "firsts". Moreover, he exhorted historians to go beyond the documents to "informed speculation" about the results of undocumented practice. What people actually did and what they thought they were doing may well not be accurately reflected in what they wrote and what they said they were thinking. His own experience had taught him that. Historians of science recognize in Hamming's point what they learned from Thomas Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions some time ago, namely that the practice of science and the literature of science do not necessarily coincide. Paradigms (or, if you prefer with Kuhn, disciplinary matrices) direct not so much what scientists say as what they do. Hence, to determine the paradigms of past science historians must watch scientists at work practicing their science. We have to reconstruct what they thought from the evidence of what they did, and that work of reconstruction in the history of science has often involved a certain amount of speculation informed by historians' own experience of science. That is all the more the case in the history of technology, where up to the present century the inventor and engineer have \*-as Derek Price once put it\*- "thought with their fingertips", leaving the record of their thinking in the artefacts they have designed rather than in texts they have written. -

Herman Heine Goldstine

Herman Heine Goldstine Born September 13, 1913, Chicago, Ill.; Army representative to the ENIAC Project, who later worked with John von Neumann on the logical design of the JAS computer which became the prototype for many early computers-ILLIAC, JOHNNIAC, MANIAC author of The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann, one of the earliest textbooks on the history of computing. Education: BS, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1933; MS, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1934; PhD, mathematics, University of Chicago, 1936. Professional Experience: University of Chicago: research assistant, 1936-1937, instructor, 1937-1939; assistant professor, University of Michigan, 1939-1941; US Army, Ballistic Research Laboratory, Aberdeen, Md., 1941-1946; Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton University, 1946-1957; IBM: director, Mathematics Sciences Department, 1958-1965, IBM fellow, 1969. Honors and Awards: IEEE Computer Society Pioneer Award, 1980; National Medal of Science, 1985; member, Information Processing Hall of Fame, Infornart, Dallas, Texas, 1985. Herman H. Goldstine began his scientific career as a mathematician and had a life-long interest in the interaction of mathematical ideas and technology. He received his PhD in mathematics from the University of Chicago in 1936 and was an assistant professor at the University of Michigan when he entered the Army in 1941. After participating in the development of the first electronic computer (ENIAC), he left the Army in 1945, and from 1946 to 1957 he was a member of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), where he collaborated with John von Neumann in a series of scientific papers on subjects related to their work on the Institute computer. In 1958 he joined IBM Corporation as a member of the research planning staff.