Language Translators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compilers & Translator Writing Systems

Compilers & Translators Compilers & Translator Writing Systems Prof. R. Eigenmann ECE573, Fall 2005 http://www.ece.purdue.edu/~eigenman/ECE573 ECE573, Fall 2005 1 Compilers are Translators Fortran Machine code C Virtual machine code C++ Transformed source code Java translate Augmented source Text processing language code Low-level commands Command Language Semantic components Natural language ECE573, Fall 2005 2 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 1 Compilers & Translators Compilers are Increasingly Important Specification languages Increasingly high level user interfaces for ↑ specifying a computer problem/solution High-level languages ↑ Assembly languages The compiler is the translator between these two diverging ends Non-pipelined processors Pipelined processors Increasingly complex machines Speculative processors Worldwide “Grid” ECE573, Fall 2005 3 Assembly code and Assemblers assembly machine Compiler code Assembler code Assemblers are often used at the compiler back-end. Assemblers are low-level translators. They are machine-specific, and perform mostly 1:1 translation between mnemonics and machine code, except: – symbolic names for storage locations • program locations (branch, subroutine calls) • variable names – macros ECE573, Fall 2005 4 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 2 Compilers & Translators Interpreters “Execute” the source language directly. Interpreters directly produce the result of a computation, whereas compilers produce executable code that can produce this result. Each language construct executes by invoking a subroutine of the interpreter, rather than a machine instruction. Examples of interpreters? ECE573, Fall 2005 5 Properties of Interpreters “execution” is immediate elaborate error checking is possible bookkeeping is possible. E.g. for garbage collection can change program on-the-fly. E.g., switch libraries, dynamic change of data types machine independence. -

Source-To-Source Translation and Software Engineering

Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2013, 6, 30-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jsea.2013.64A005 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jsea) Source-to-Source Translation and Software Engineering David A. Plaisted Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, USA. Email: [email protected] Received February 5th, 2013; revised March 7th, 2013; accepted March 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 David A. Plaisted. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Source-to-source translation of programs from one high level language to another has been shown to be an effective aid to programming in many cases. By the use of this approach, it is sometimes possible to produce software more cheaply and reliably. However, the full potential of this technique has not yet been realized. It is proposed to make source- to-source translation more effective by the use of abstract languages, which are imperative languages with a simple syntax and semantics that facilitate their translation into many different languages. By the use of such abstract lan- guages and by translating only often-used fragments of programs rather than whole programs, the need to avoid writing the same program or algorithm over and over again in different languages can be reduced. It is further proposed that programmers be encouraged to write often-used algorithms and program fragments in such abstract languages. Libraries of such abstract programs and program fragments can then be constructed, and programmers can be encouraged to make use of such libraries by translating their abstract programs into application languages and adding code to join things together when coding in various application languages. -

COM 113 INTRO to COMPUTER PROGRAMMING Theory Book

1 [Type the document title] UNESCO -NIGERIA TECHNICAL & VOCATIONAL EDUCATION REVITALISATION PROJECT -PHASE II NATIONAL DIPLOMA IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY Computer Programming COURSE CODE: COM113 YEAR I - SE MESTER I THEORY Version 1: December 2008 2 [Type the document title] Table of Contents WEEK 1 Concept of programming ................................................................................................................ 6 Features of a good computer program ............................................................................................ 7 System Development Cycle ............................................................................................................ 9 WEEK 2 Concept of Algorithm ................................................................................................................... 11 Features of an Algorithm .............................................................................................................. 11 Methods of Representing Algorithm ............................................................................................ 11 Pseudo code .................................................................................................................................. 12 WEEK 3 English-like form .......................................................................................................................... 15 Flowchart ..................................................................................................................................... -

Executable Code Is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law a Retrospective Criticism of Technical and Legal Naivete in the Apple V

Executable Code is Not the Proper Subject of Copyright Law A retrospective criticism of technical and legal naivete in the Apple V. Franklin case Matthew M. Swann, Clark S. Turner, Ph.D., Department of Computer Science Cal Poly State University November 18, 2004 Abstract: Copyright was created by government for a purpose. Its purpose was to be an incentive to produce and disseminate new and useful knowledge to society. Source code is written to express its underlying ideas and is clearly included as a copyrightable artifact. However, since Apple v. Franklin, copyright has been extended to protect an opaque software executable that does not express its underlying ideas. Common commercial practice involves keeping the source code secret, hiding any innovative ideas expressed there, while copyrighting the executable, where the underlying ideas are not exposed. By examining copyright’s historical heritage we can determine whether software copyright for an opaque artifact upholds the bargain between authors and society as intended by our Founding Fathers. This paper first describes the origins of copyright, the nature of software, and the unique problems involved. It then determines whether current copyright protection for the opaque executable realizes the economic model underpinning copyright law. Having found the current legal interpretation insufficient to protect software without compromising its principles, we suggest new legislation which would respect the philosophy on which copyright in this nation was founded. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 THE ORIGIN OF COPYRIGHT ........................................................................... 1 The Idea is Born 1 A New Beginning 2 The Social Bargain 3 Copyright and the Constitution 4 THE BASICS OF SOFTWARE .......................................................................... -

Tdb: a Source-Level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs

Tdb: A Source-level Debugger for Dynamically Translated Programs Naveen Kumar†, Bruce R. Childers†, and Mary Lou Soffa‡ †Department of Computer Science ‡Department of Computer Science University of Pittsburgh University of Virginia Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260 Charlottesville, Virginia 22904 {naveen, childers}@cs.pitt.edu [email protected] Abstract single stepping through program execution, watching for par- ticular conditions and requests to add and remove breakpoints. Debugging techniques have evolved over the years in response In order to respond, the debugger has to map the values and to changes in programming languages, implementation tech- statements that the user expects using the source program niques, and user needs. A new type of implementation vehicle viewpoint, to the actual values and locations of the statements for software has emerged that, once again, requires new as found in the executable program. debugging techniques. Software dynamic translation (SDT) As programming languages have evolved, new debugging has received much attention due to compelling applications of techniques have been developed. For example, checkpointing the technology, including software security checking, binary and time stamping techniques have been developed for lan- translation, and dynamic optimization. Using SDT, program guages with concurrent constructs [6,19,30]. The pervasive code changes dynamically, and thus, debugging techniques use of code optimizations to improve performance has necessi- developed for statically generated code cannot be used to tated techniques that can respond to queries even though the debug these applications. In this paper, we describe a new optimization may have changed the number of statement debug architecture for applications executing with SDT sys- instances and the order of execution [15,25,29]. -

Studying the Real World Today's Topics

Studying the real world Today's topics Free and open source software (FOSS) What is it, who uses it, history Making the most of other people's software Learning from, using, and contributing Learning about your own system Using tools to understand software without source Free and open source software Access to source code Free = freedom to use, modify, copy Some potential benefits Can build for different platforms and needs Development driven by community Different perspectives and ideas More people looking at the code for bugs/security issues Structure Volunteers, sponsored by companies Generally anyone can propose ideas and submit code Different structures in charge of what features/code gets in Free and open source software Tons of FOSS out there Nearly everything on myth Desktop applications (Firefox, Chromium, LibreOffice) Programming tools (compilers, libraries, IDEs) Servers (Apache web server, MySQL) Many companies contribute to FOSS Android core Apple Darwin Microsoft .NET A brief history of FOSS 1960s: Software distributed with hardware Source included, users could fix bugs 1970s: Start of software licensing 1974: Software is copyrightable 1975: First license for UNIX sold 1980s: Popularity of closed-source software Software valued independent of hardware Richard Stallman Started the free software movement (1983) The GNU project GNU = GNU's Not Unix An operating system with unix-like interface GNU General Public License Free software: users have access to source, can modify and redistribute Must share modifications under same -

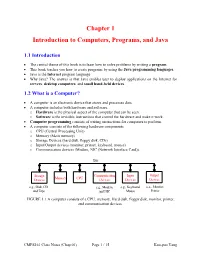

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Some Preliminary Implications of WTO Source Code Proposala INTRODUCTION

Some preliminary implications of WTO source code proposala INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 HOW THIS IS TRIMS+ ....................................................................................................................................... 3 HOW THIS IS TRIPS+ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE TRANSFER OF SOURCE CODE .................................................................. 4 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ........................................................................................................................................... 4 AS A REMEDY FOR ANTICOMPETITIVE CONDUCT ............................................................................................................. 4 TAX LAW ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 IN GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT ................................................................................................................................ 5 WHY GOVERNMENTS MAY REQUIRE ACCESS TO SOURCE CODE ...................................................................... 5 COMPETITION LAW ................................................................................................................................................. -

Virtual Machine Part II: Program Control

Virtual Machine Part II: Program Control Building a Modern Computer From First Principles www.nand2tetris.org Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, Part II slide 1 Where we are at: Human Abstract design Software abstract interface Thought Chapters 9, 12 hierarchy H.L. Language Compiler & abstract interface Chapters 10 - 11 Operating Sys. Virtual VM Translator abstract interface Machine Chapters 7 - 8 Assembly Language Assembler Chapter 6 abstract interface Computer Machine Architecture abstract interface Language Chapters 4 - 5 Hardware Gate Logic abstract interface Platform Chapters 1 - 3 Electrical Chips & Engineering Hardware Physics hierarchy Logic Gates Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, Part II slide 2 The big picture Some . Some Other . Jack language language language Chapters Some Jack compiler Some Other 9-13 compiler compiler Implemented in VM language Projects 7-8 VM implementation VM imp. VM imp. VM over the Hack Chapters over CISC over RISC emulator platforms platforms platform 7-8 A Java-based emulator CISC RISC is included in the course written in Hack software suite machine machine . a high-level machine language language language language Chapters . 1-6 CISC RISC other digital platforms, each equipped Any Hack machine machine with its VM implementation computer computer Elements of Computing Systems, Nisan & Schocken, MIT Press, www.nand2tetris.org , Chapter 8: Virtual Machine, -

Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases

Michigan Law Review Volume 91 Issue 3 1992 Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases John W.L. Ogilive University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ogilive, Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases, 91 MICH. L. REV. 526 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol91/iss3/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE Defining Computer Program Parts Under Learned Hand's Abstractions Test in Software Copyright Infringement Cases John W.L. Ogilvie INTRODUCTION Although computer programs enjoy copyright protection as pro tectable "literary works" under the federal copyright statute, 1 the case law governing software infringement is confused, inconsistent, and even unintelligible to those who must interpret it.2 A computer pro gram is often viewed as a collection of different parts, just as a book or play is seen as an amalgamation of plot, characters, and other familiar parts. However, different courts recognize vastly different computer program parts for copyright infringement purposes. 3 Much of the dis array in software copyright law stems from mutually incompatible and conclusory program part definitions that bear no relation to how a computer program is actually designed and created. -

Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK

1 From Start-ups to Scale-ups: Opportunities and Open Problems for Static and Dynamic Program Analysis Mark Harman∗, Peter O’Hearn∗ ∗Facebook London and University College London, UK Abstract—This paper1 describes some of the challenges and research questions that target the most productive intersection opportunities when deploying static and dynamic analysis at we have yet witnessed: that between exciting, intellectually scale, drawing on the authors’ experience with the Infer and challenging science, and real-world deployment impact. Sapienz Technologies at Facebook, each of which started life as a research-led start-up that was subsequently deployed at scale, Many industrialists have perhaps tended to regard it unlikely impacting billions of people worldwide. that much academic work will prove relevant to their most The paper identifies open problems that have yet to receive pressing industrial concerns. On the other hand, it is not significant attention from the scientific community, yet which uncommon for academic and scientific researchers to believe have potential for profound real world impact, formulating these that most of the problems faced by industrialists are either as research questions that, we believe, are ripe for exploration and that would make excellent topics for research projects. boring, tedious or scientifically uninteresting. This sociological phenomenon has led to a great deal of miscommunication between the academic and industrial sectors. I. INTRODUCTION We hope that we can make a small contribution by focusing on the intersection of challenging and interesting scientific How do we transition research on static and dynamic problems with pressing industrial deployment needs. Our aim analysis techniques from the testing and verification research is to move the debate beyond relatively unhelpful observations communities to industrial practice? Many have asked this we have typically encountered in, for example, conference question, and others related to it. -

A Brief History of Just-In-Time Compilation

A Brief History of Just-In-Time JOHN AYCOCK University of Calgary Software systems have been using “just-in-time” compilation (JIT) techniques since the 1960s. Broadly, JIT compilation includes any translation performed dynamically, after a program has started execution. We examine the motivation behind JIT compilation and constraints imposed on JIT compilation systems, and present a classification scheme for such systems. This classification emerges as we survey forty years of JIT work, from 1960–2000. Categories and Subject Descriptors: D.3.4 [Programming Languages]: Processors; K.2 [History of Computing]: Software General Terms: Languages, Performance Additional Key Words and Phrases: Just-in-time compilation, dynamic compilation 1. INTRODUCTION into a form that is executable on a target platform. Those who cannot remember the past are con- What is translated? The scope and na- demned to repeat it. ture of programming languages that re- George Santayana, 1863–1952 [Bartlett 1992] quire translation into executable form covers a wide spectrum. Traditional pro- This oft-quoted line is all too applicable gramming languages like Ada, C, and in computer science. Ideas are generated, Java are included, as well as little lan- explored, set aside—only to be reinvented guages [Bentley 1988] such as regular years later. Such is the case with what expressions. is now called “just-in-time” (JIT) or dy- Traditionally, there are two approaches namic compilation, which refers to trans- to translation: compilation and interpreta- lation that occurs after a program begins tion. Compilation translates one language execution. into another—C to assembly language, for Strictly speaking, JIT compilation sys- example—with the implication that the tems (“JIT systems” for short) are com- translated form will be more amenable pletely unnecessary.