Airpower Journal: Fall 1993, Volume VII, No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Infantrymen

1st Cavalry Division Association Non-Profit Organization 302 N. Main St. US. Postage PAID Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 West, TX 76691 Change Service Requested Permit No. 39 SABER Published By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 69 NUMBER 4 Website: www.1CDA.org JULY / AUGUST 2020 This has been a HORSE DETACHMENT by CPT Siddiq Hasan, Commander THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER year different from We thundered into the summer change of command season with a cavalry Allen Norris any other for most of charge for 3rd ABCT’s change of command at the end of June. Our new First (704) 483-8778 us. By the time you Sergeant was welcomed into the ranks at the beginning of July at a key time in [email protected] read this Cathy and I our history with few public events taking place due to COVID-19 but a lot of will have moved into foundational training taking place. We have taken this opportunity to conduct temporary housing. Sometime ago Cathy and I talked about the need to downsize. intensive horsemanship training for junior riders, green horses and to continue Until this year it was always something to consider later. In January we decided with facility improvements. The Troopers are working hard every day while that it was time. We did not want to be in a retirement community. We would like taking the necessary precautions in this distanced work environment to keep more diversity. Also, in those communities you have to pay for amenities that we themselves and the mounts we care for healthy. -

Vietnam War Turning Back the Clock 93 Year Old Arctic Convoy Veteran Visits Russian Ship

Military Despatches Vol 33 March 2020 Myths and misconceptions Things we still get wrong about the Vietnam War Turning back the clock 93 year old Arctic Convoy veteran visits Russian ship Battle of Ia Drang First battle between the Americans and NVA For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2020 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Page 14 Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, South Vietnamese Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 32 were humorous, some Weapons and equipment were clever, while others 6 We look at some of the uniforms were downright crude. Ten myths about Vietnam and equipment used by the US Marine Corps in Vietnam dur- Although it ended almost 45 ing the 1960s years ago, there are still many Part of Hipe’s “On the myths and misconceptions 34 couch” series, this is an about the Vietnam War. We A matter of survival 26 interview with one of look at ten myths and miscon- This month we look at fish and author Herman Charles ceptions. ‘Mad Mike’ dies aged 100 fishing for survival. Bosman’s most famous 20 Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare, characters, Oom Schalk widely considered one of the 30 Turning back the clock Ranks Lourens. Hipe spent time in world’s best known mercenary, A taxi driver was shot When the Russian missile cruis- has died aged 100. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Hunting the Collectors Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives

Hunting the Collectors Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives Edited by SUSAN COCHRANE and MAX QUANCHI Cambridge Scholars Publishing HUNTING THE COLLECTORS Hunting the Collectors: Pacific Collections in Australian Museums, Art Galleries and Archives Edited by Susan Cochrane and Max Quanchi This book first published 2007 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK Second edition published 2010 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright ©2007 by Susan Cochrane and Max Quanchi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-084-1, ISBN (13): 9781847180841 Chapter 3 The perils of ethnographic provenance: the documentation of the Johnson Fiji Collection in the South Australian Museum RODERICK EWINS 3 HUNTING THE COLLECTORS The perils of ethnographic provenance: the documentation of the Johnson Fiji Collection in the South Australian Museum RODERICK EWINS This essay addresses the vexed questions of provenance and authenticity of objects that have been collected and made accessible for study. It calls for an exploration of the way in which these have often been uncritically accepted solely on the basis of notes and comments made by the original collectors. The difficulty is that the authority with which collectors were able to speak varied enormously, and even when the collectors obtained objects personally from the original owners, it cannot be assumed that they understood clearly the names, purposes or provenance of the objects they obtained. -

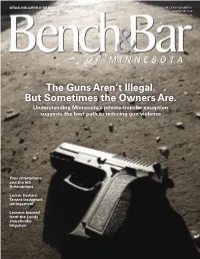

The Guns Aren't Illegal. but Sometimes the Owners Are

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE MINNESOTA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION VOLUME LXXVI NUMBER V MAY/JUNE 2019 www.mnbar.org The Guns Aren’t Illegal. But Sometimes the Owners Are. Understanding Minnesota’s private-transfer exception suggests the best path to reducing gun violence Your smartphone and the 5th Amendment Lessor beware: Tenant trademark infringement Lessons learned from the Lunds shareholder litigation Only 2019 MSBA CONVENTION $125 June 27 & 28, 2019 • Mystic Lake Center • www.msbaconvention.org for MSBA Members EXPERIENCE THE BEST 12:15 – 12:30 p.m. 4:00 – 5:00 p.m. 9:40 – 10:40 a.m. THURSDAY, JUNE 27 Remarks by American Bar Association President ED TALKS BREAKOUT SESSION D OF THE BAR Bob Carlson 7:30 – 8:30 a.m. • Making the Case for Sleep 401) Someone Like Me Can Do This – CHECK-IN & CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 12:30 – 12:45 p.m. Dr. John Parker; Sleep Performance Institute; Minneapolis Stories of Latino Lawyers and Judges What do lawyers, judges, academics, activists, technologists and business leaders in Minnesota Passing of the Gavel Ceremony have in common? They will all be at the 2019 MSBA Convention engaging in a rich, 7:45 – 8:30 a.m. • Transformational Metaphors 1.0 elimination of bias credit applied for Paul Godfrey, MSBA President Madge S. Thorsen; Law Offices of Madge S. Thorsen; rewarding educational experience. Aleida O. Conners; Cargill, Inc.; Wayzata SUNRISE SESSIONS Tom Nelson, Incoming MSBA President Minneapolis Roger A. Maldonado; Faegre Baker Daniels LLP; This year’s convention combines thoughtful presentations on the legal profession Minneapolis and “critical conversations” about timely issues with important legal updates and • Cheers and Jeers: Expert Reviews of 12:45 – 1:15 p.m. -

Natural History Guide to American Samoa

NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE TO AMERICAN SAMOA rd 3 Edition NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE This Guide may be available at: www.nps.gov/npsa Support was provided by: National Park of American Samoa Department of Marine & Wildlife Resources American Samoa Community College Sport Fish & Wildlife Restoration Acts American Samoa Department of Commerce Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawaii American Samoa Coral Reef Advisory Group National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Natural History is the study of all living things and their environment. Cover: Ofu Island (with Olosega in foreground). NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE TO AMERICAN SAMOA 3rd Edition P. Craig Editor 2009 National Park of American Samoa Department Marine and Wildlife Resources Pago Pago, American Samoa 96799 Box 3730, Pago Pago, American Samoa American Samoa Community College Community and Natural Resources Division Box 5319, Pago Pago, American Samoa NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE Preface & Acknowledgments This booklet is the collected writings of 30 authors whose first-hand knowledge of American Samoan resources is a distinguishing feature of the articles. Their contributions are greatly appreciated. Tavita Togia deserves special recognition as contributing photographer. He generously provided over 50 exceptional photos. Dick Watling granted permission to reproduce the excellent illustrations from his books “Birds of Fiji, Tonga and Samoa” and “Birds of Fiji and Western Polynesia” (Pacificbirds.com). NOAA websites were a source of remarkable imagery. Other individuals, organizations, and publishers kindly allowed their illustrations to be reprinted in this volume; their credits are listed in Appendix 3. Matt Le'i (Program Director, OCIA, DOE), Joshua Seamon (DMWR), Taito Faleselau Tuilagi (NPS), Larry Basch (NPS), Tavita Togia (NPS), Rise Hart (RCUH) and many others provided assistance or suggestions throughout the text. -

Degei's Descendants: Spirits, Place and People in Pre-Cession Fiji

terra australis 41 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. C. Schrire (1982) Volume 8: Hunter Hill, Hunter Island: Archaeological Investigations of a Prehistoric Tasmanian Site. S. Bowdler (1984) Volume 9: Coastal South-West Tasmania: The Prehistory of Louisa Bay and Maatsuyker Island. R. Vanderwal and D. Horton (1984) Volume 10: The Emergence of Mailu. G. Irwin (1985) Volume 11: Archaeology in Eastern Timor, 1966–67. I. Glover (1986) Volume 12: Early Tongan Prehistory: The Lapita Period on Tongatapu and its Relationships. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1991, No.5

www.ukrweekly.com 5 Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association! crainian Weekl V Vol. LIX No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 3,1991 50 cents Democratic congress in Kharkiv Coordinating Committee to Aid Ukraine unites republics' opposition consolidates US. support organizations by Marta Kolomayets continue to centralize power in Mos by Chrystyna N. Lapychak tions, and elected a board of directors, KIEV — Representatives of demo cow. executive board and other leadership cratic parties, organizations and move They suggested that a referendum ELIZABETH, N.J. - In the "spirit organs for the new coordinating body. ments from 10 Soviet republics gathered take place in each republic, asking: "Do of consolidation," called for by Ukrai "the birth of anything new is never in Kharkiv to form a coalition of you consider it necessary to transform nian People's Deputy Mykhailo Horyn, easy," stated Mr. Horyn, chairman of democratic forces during the weekend the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics some 90 delegates from all over the Rukh's Political Council, whose key of January 26-27, reported Dmytro into a commonwealth of sovereign United States gathered at the Holiday note address on Saturday, January 26, Ponamarchuk, senior editor at Kiev states in which the rights of citizens will Inn Jetport here on January 26-27 to detailing the needs of Ukraine's demo State Radio. be fully guaranteed through the mutual found the U.S. Coordinating Commit cratic movement was one of the high The meeting, which carried the offi obligations of states?" tee to Aid Ukraine. -

Loanword Strata in Rotuman

Loanword Strata in Rotuman by Hans Schmidt In Language Contacts in Prehistory: Studies in Stratigraphy: Papers from the Workshop on Linguistic Stratigraphy and Prehistory at the Fifteenth International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Melbourne, 17 August 2001, pp. 201-240 (2003). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Co. (c) 2003 John Benjamins Publishing Company. Not to be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. LOANWORD STRATA IN ROTUMAN Hans Schmidt University of the South Pacific, Vanuatu 1. Introduction Rotuma is a small island in the South Pacific.1 It lies roughly at the crossroads of Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. Politically, the island forms part of the Republic of Fiji; though the closest Fijian island, Cikobia, is about 465 km distant (Woodhall 1987:1). The island is accessible from Suva, the capital of Fiji, by a two-day boat trip or in two hours by plane. In contrast to its Northern neighbor Tuvalu, Rotuma is not a coral atoll but a so called ‘high’ island of volcanic origin (Pleistocene), its surface area is 46 km2 and its soil is very fertile. Rotuma has a population of approximately 2,700 inhabitants who live in twenty villages scattered along the coast. This constitutes the highest population density (59 per km2) for all Fijian islands (Walsh 1982:20), although three quarters of the Rotumans have left their home island for the urban areas of Fiji or overseas. Many of these Fiji-Rotumans have never been on Rotuma or at most for a brief Christmas holiday. In contrast to its small number of speakers, Rotuman has featured frequently in works of general and comparative linguistics.2 What makes Rotuman so interesting in the eyes of linguists? Its productive metathesis. -

THE FIJIAN LANGUAGE the FIJIAN LANGU AGE the FIJIAN LANGUAGE Albert J

THE FIJIAN LANGUAGE THE FIJIAN LANGU AGE THE FIJIAN LANGUAGE Albert J. Schütz University of Hawaii Press Honolulu Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824881658 (PDF) 9780824881665 (EPUB) This version created: 29 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1985 BY ALBERT J. SCHÜTZ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Fijian Language is dedicated to the two people who have most inspired and encouraged my study of Fijian—Charles F. Hockett, of Cornell University, and G. B. Milner, of the School of Oriental and African studies, University of London. The completion of this grammar nearly coincides with their respective retirements, and I offer it as a festschrift for the occasion. May we continue discussing, (perhaps) disagreeing, and—above all—learning about Fijian. By the term Fijian language … I mean the language of the predominant race of people resident in what have been long known as the Fiji Islands and which is fast becoming the lingua franca of the whole group … “The Fijian Language” Beauclerc 1908–10b:65 Bau is the Athens of Fiji, the dialect there spoken has now become the classical dialect of the whole group. -

SKI Report 2003:18 Research Making a Historical Survey of a State's Nuclear Ambitions

SKI Report 2003:18 Research Making a Historical Survey of a State's Nuclear Ambitions IAEA task ID: SWE C 01333 Impact of Historical Developments of a State’s National Nuclear Non-Proliferation Policy on Additional Protocol Implementation Dr. Thomas Jonter March 2003 ISSN 1104–1374 ISRN SKI-R-03/18-SE SKI’s perspective Background In the year 1998 Sweden, together with the rest of the states in the European Union and Euratom signed the Additional Protocol to the Safeguard Agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA. The Additional Protocol gives the Agency the right of more information on the nuclear fuel cycle activities in the State. The Protocol also gives extended access to areas and buildings and rights to take environmental samples within a state. The process of ratification is going on and the Protocol will be implemented simultaneously in all EU-member states. In ratifying the agreement in May 2000, Sweden changed its Act on Nuclear Activities and passed a new act regarding access. The present estimate is that the protocol could be implemented in EU during the second half of 2003. Aim When the Additional Protocol is implemented, Sweden (and the other EU-states) is to be “mapped” by the IAEA, scrutinising all nuclear activities, present as well as future plans. In the light of this, SKI has chosen to go one step further, letting Dr Thomas Jonter of the Stockholm University investigate Sweden’s past activities in the area of nuclear weapons research in a political perspective. Since Sweden had plans in the nuclear weapons area it is important to show to the IAEA that all such activities have stopped. -

IF YOU WANT a GOOD FIGHT...” UPI Combat Correspondent Joins the Cavalry

71658 55096 “IF YOU WANT A GOOD FIGHT...” UPI Combat Correspondent Joins the Cavalry Text & Photos by Joe Galloway Editor’s Note: When SOF first received when it was taking you somewhere you Mang Yang Pass between Anh Khe and Robert Oles’ two-part series on the Plei didn’t really want to go. Pleiku was enough to raise the hair on the Me/Ia Drang Valley/Chu Pong Mountain From the airstrip at Camp Holloway I back of our necks. It was only 12 short years campaign (see “Bloody la Drang” and hitched a jeep ride over to MACV where I since Vo Nguyen Giap’s regulars ate up GM “Winning One for Gary Owen,” SOF, found the public information officer (PIO), 100 and now another North Vietnamese March, April ’83), we immediately began Capt. Larry Brown, a cordial host dispens army was building for battle in the high searching for an eye-witness account to ing bunks in his animal room, or mosquito lands. accompany it. Executive Editor Bob Poos heaven as we also called it, where the com Unknown to us at the time, Hanoi the recalled that Joe Galloway, then a UPI re mand chaplain sat in on a nightly poker previous June had established the B-3 West porter/photographer, had been at L Z X-Ray game and was widely accused of rattling his ern Highlands Front under direct North all during the battle there. He contacted beads when drawing to inside straights. Vietnamese control. The NLF, the Viet Galloway, who consented to do an on-the- From MACV I could hop back to Hollo Cong, had nothing to do with this.