East and West Gulf Coastal Plain: Open Pine/Savanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Report

Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Report ## by Legend Paul R. Knox, P.G. State Line Shelf Edge Yegua-Jackson outcrop Van A. Kelley, P.G. County Boundaries Well Locations Astrid Vreugdenhil Sediment Input Axis (Size Relative to Sed. Vol.) Facies Neil Deeds, P.E. Deltaic/Delta Front/Strandplain Wave-Dominated Delta Steven Seni, Ph.D., P.G. Delta Margin < 100' Fluvial Floodplain Slope 020406010 Miles Shelf-Edge Delta Shelf/Slope Sand > 100' Texas Water Development Board P.O. Box 13231, Capitol Station Austin, Texas 7871-3231 September 2007 TWDB Report ##: Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Texas Water Development Board Report ## Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain by Van A. Kelley, P.G. Astrid Vreugdenhil Neil Deeds, P.E. INTERA Incorporated Paul R. Knox, P.G. Baer Engineering and Environmental Consulting, Incorporated Steven Seni, Ph.D., P.G. Consulting Geologist September 2007 This page is intentionally blank. ii This page is intentionally blank. iv TWDB Report ##: Structure of the Yegua-Jackson Aquifer of the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................................E-i 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1-1 2. Study Area and Geologic Setting....................................................................................... -

Subsurface Geology of Cenozoic Deposits, Gulf Coastal Plain, South-Central United States

REGIONAL STRATIGRAPHY AND _^ SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF CENOZOIC DEPOSITS, GULF COASTAL PLAIN, SOUTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES V U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1416-G AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications re leased prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that may be listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" may no longer be available. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices listed below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books and Maps Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books and maps of the U.S. Geological Survey are available niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications over the counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Docu copies of Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of ments. Epicenters, and some miscellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from ANCHORAGE, Alaska-Rm. -

Draft Environmental Assessment for Review and Comment

United States Department ofthe Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Texas Chenier Plain NWR Complex June 15, 2017 Dear Reviewer: This is to provide notification of availability of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Draft Environmental Assessment for review and comment. The Draft Environmental Assessment addresses the issuance of an Operational Permit by the USFWS for two proposed oil and natural gas drilling and production project on the Mcfaddin National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge) in Jefferson County, Texas. The project has been proposed by OLEUM Exploration, LLC ofBrodheadsville, Pennsylvania. The company possesses valid leases to explore and/or develop oil and gas reserves underlying the refuge from the rightful mineral owners. The purpose for the proposed Federal action is to insure that mineral rights holders have reasonable access to develop their non-Federal oil and gas interests and minimize impacts to refuge resources to the extent practicable under the USFWS's 50 CFR Part 29, Subpart D regulations for managing non-Federal oil and gas on USFWS administered lands and waters. Issuance ofthe Operations Permit in the end should protect the human environment in such a way as to further the Refuge's efforts to achieve its established purposes, and the general resource conservation mission ofthe USFWS. Written comments may be mailed to Texas Chenier Plain Refuge Complex at P.O. Box 278, Anahuac, TX 77514. Comments may also be electronically mailed to monique [email protected] with "OLEUM EA Comments" in the subject line. All comments sent must be post marked or electronically sent by June 29th, 2017. If you need additional information, feel free to visit our offices or contact myself, Monique Slaughter, Oil and Gas Specialist for the refuge complex (409) 267-3337 or Refuge Manager Douglas Head at (409) 971-2909. -

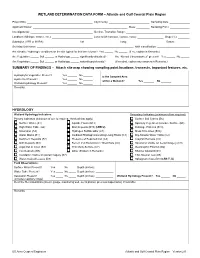

Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region SUMMARY of FINDINGS

WETLAND DETERMINATION DATA FORM – Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region Project/Site: City/County: Sampling Date: Applicant/Owner: State: Sampling Point: Investigator(s): Section, Township, Range: Landform (hillslope, terrace, etc.): Local relief (concave, convex, none): Slope (%): Subregion (LRR or MLRA): Lat: Long: Datum: Soil Map Unit Name: NWI classification: Are climatic / hydrologic conditions on the site typical for this time of year? Yes No (If no, explain in Remarks.) Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology significantly disturbed? Are “Normal Circumstances” present? Yes No Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology naturally problematic? (If needed, explain any answers in Remarks.) SUMMARY OF FINDINGS – Attach site map showing sampling point locations, transects, important features, etc. Hydrophytic Vegetation Present? Yes No Is the Sampled Area Hydric Soil Present? Yes No within a Wetland? Yes No Wetland Hydrology Present? Yes No Remarks: HYDROLOGY Wetland Hydrology Indicators: Secondary Indicators (minimum of two required) Primary Indicators (minimum of one is required; check all that apply) Surface Soil Cracks (B6) Surface Water (A1) Aquatic Fauna (B13) Sparsely Vegetated Concave Surface (B8) High Water Table (A2) Marl Deposits (B15) (LRR U) Drainage Patterns (B10) Saturation (A3) Hydrogen Sulfide Odor (C1) Moss Trim Lines (B16) Water Marks (B1) Oxidized Rhizospheres along Living Roots (C3) Dry-Season Water Table (C2) Sediment Deposits (B2) Presence of Reduced Iron (C4) Crayfish Burrows (C8) Drift Deposits (B3) Recent Iron Reduction -

West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine

Rapid Assessment Reference Condition Model The Rapid Assessment is a component of the LANDFIRE project. Reference condition models for the Rapid Assessment were created through a series of expert workshops and a peer-review process in 2004 and 2005. For more information, please visit www.landfire.gov. Please direct questions to [email protected]. Potential Natural Vegetation Group (PNVG) R5GCPP West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine -- Uplands + Flatwoods General Information Contributors (additional contributors may be listed under "Model Evolution and Comments") Modelers Reviewers Maria Melnechuk [email protected] In worshop review Mike Melnechuk [email protected] Doug Zollner [email protected] Doug Zollner [email protected] Vegetation Type General Model Sources Rapid AssessmentModel Zones Forested Literature California Pacific Northwest Local Data Great Basin South Central Dominant Species* Expert Estimate Great Lakes Southeast Northeast S. Appalachians PITA LANDFIRE Mapping Zones PIEC Northern Plains Southwest 37 N-Cent.Rockies QUER 44 ANDR 45 Geographic Range This PNVG lies in Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and SE Oklahoma. The West Gulf Coastal Plain Pine- Hardwood Forest type is found over a large area of the South Central model zone. It is the predominate vegetation system over most of the Upper West Gulf Coastal Plain ecoregion with smaller incursions into the southern Interior Highlands (Ecological Classification CES203.378). The flatwoods communities represent predominately dry flatwoods of limited areas of the inland portions of West Gulf Coastal Plain. (Ecological Classification CES203.278) Biophysical Site Description This PNVG was historically present on nearly all uplands in the region except on the most edaphically limited sites (droughty sands, calcareous clays, and shallow soil barrens/rock outcrops). -

Western Gulf Coastal Plains

Ecological Systems Midsize Report INTERNATIONAL ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION STANDARD: TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATIONS Ecological Systems of Texas’ West Gulf Coastal Plain 08 October 2009 by NatureServe 1101 Wilson Blvd., 15th floor Arlington, VA 22209 This subset of the International Ecological Classification Standard covers terrestrial ecological systems attributed to the Texas. This classification has been developed in consultation with many individuals and agencies and incorporates information from a variety of publications and other classifications. Comments and suggestions regarding the contents of this subset should be directed to [Judy Teague <[email protected]>]. Copyright © 2009 NatureServe, 1101 Wilson Blvd, 15th floor Arlington, VA 22209, U.S.A. All Rights Reserved. Citations: The following citation should be used in any published materials which reference ecological system and/or International Vegetation Classification (IVC hierarchy) and association data: NatureServe. 2009. International Ecological Classification Standard: Terrestrial Ecological Classifications. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A. Data current as of 08 October 2009. 1 Copyright © 2009 NatureServe Printed from Biotics on: 8 Oct 2009 Subset: TX systems Ecological Systems Midsize Report TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREST AND WOODLAND ..................................................................................................... 3 CES205.679 East-Central Texas Plains Post Oak Savanna and Woodland .............................................................. -

IC-25 Subsurface Geology of the Georgia Coastal Plain

IC 25 GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 25 SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA COASTAL PLAIN by Stephen M. Herrick and Robert C. Vorhis United States Geological Survey ~ ......oi············· a./!.. z.., l:r '~~ ~= . ·>~ a··;·;;·;· .......... Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1963 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .................................................. , . 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Previous work . • • • • • • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • . • • • • . • . • . • 2 Mapping methods . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • • . • . • 7 Cooperation, administration, and acknowledgments . • . • . • . • • • • . • • • • . • 8 STRATIGRAPHY. 9 Quaternary and Tertiary Systems . • . • • . • • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • . 10 Recent to Miocene Series . • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • • . • . 10 Tertiary System . • • . • • • . • . • • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • . 13 Oligocene Series • . • . • . • . • • • . • • . • • . • . • • . • . • • • . 13 Eocene Series • . • • • . • • • • . • . • • . • . • • • . • • • • . • . • . 18 Upper Eocene rocks . • • • . • . • • • . • . • • • . • • • • • . • . • . • 18 Middle Eocene rocks • . • • • . • . • • • • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • . • • . • 25 Lower Eocene rocks . • . • • • • . • • • • • . • • . • . 32 Paleocene Series . • . • . • • . • • • . • • . • • • • . • . • . • • . • • . • . 36 Cretaceous System . • . • . • • . • . • -

Confronting Climate Change in the Gulf Coast Region

Confronting Climate Change in the Gulf Coast Prospects for Sustaining Our Region Ecological Heritage Appalachian Piedmont North Central TX/OK Plain Central Southern Plain Southeastern Texas Plain Southern Plain Coastal Plain CentralPlateau Texas Mississippi River Western Gulf Coastal Plain Deltaic Plain South Mississippi River Texas Alluvial Plain Plain Texas Claypan South Florida Area Gulf of Mexico Coastal Plain Florida Keys A REPORT OF The Union of Concerned Scientists and The Ecological Society of America Confronting Climate Change in the Gulf Coast Region Prospects for Sustaining Our Ecological Heritage PREPARED BY Robert R. Twilley Eric J. Barron Henry L. Gholz Mark A. Harwell Richard L. Miller Denise J. Reed Joan B. Rose Evan H. Siemann Robert G. Wetzel Roger J. Zimmerman October 2001 A REPORT OF The Union of Concerned Scientists and The Ecological Society of America CONFRONTING CLIMATE CHANGE IN CALIFORNIA 1 Union of Concerned Scientists • The Ecological Society of America Citation: Twilley, R.R., E.J. Barron, H.L. Gholz, M.A. Harwell, R.L. Miller, D.J. Reed, J.B. Rose, E.H. Siemann, R.G. Wetzel and R.J. Zimmerman (2001). Confronting Climate Change in the Gulf Coast Region: Prospects for Sustaining Our Ecological Heritage. Union of Concerned Scientists, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Ecological Society of America, Washington, D.C. © 2001 Union of Concerned Scientists & Ecological Society of America All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Designed by DG Communications, Acton, Massachusetts (www.nonprofitdesign.com) Printed on recycled paper. Copies of this report are available from UCS Publications, Two Brattle Square, Cambridge, MA 02238–9105 Tel. -

A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia

A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia THE OLIGOCENE Paul F. Huddleston DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION GEORGIA GEOLOGIC SURVEY I BULLETIN 105 Cover photo: Seventy feet of Bridgeboro Limestone exposed at the the type locality in the southern-most pit of the Bridgeboro Lime and Stone Company, 6.5 miles west-southwest of the community of Bridgeboro, south of Georgia 112, Mitchell County. A Revision of the Lithostratigraphic Units of the Coastal Plain of Georgia THE OLIGOCENE Paul F. Huddlestun ·Georgia Department of Natural Resources Joe D. Tanner, Commissioner Environmental Protection Division Harold F. Reheis, Director Georgia Geologic Survey William H. McLemore, State Geologist Atlanta 1993 BULLETIN 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 ACKN"OWLEIJGMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. :.............................. 2 Methods ........................................... ,................................................................................................................... -

Famous People with Arkansas Connections” Than Any Other Region? Why?

FRAMEWORK(s): H.6.2.3, H.6.3.2 GRADE LEVEL(s): Designed for grades 2 and 3, but can be adapted for grades K - 8 TASK: Students shall analyze significant ideas, events, and people in world, national, state, and local history and how they affect change over time. Be the first player to cover five squares horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. APPROXIMATE TIME: Three to four class periods MATERIALS: pre-printed bingo card with famous persons’ names in squares and a free square in the center for each student. Handout #1 One copy of the names with descriptions sheet should be cut apart to use as ‘Fact Cards.’Paper ‘chips’ to use on bingo card. Free square should be covered PROCEDURE: 1. Students will be instructed to randomly choose names from the list. Students should review the description but write only the name. These should be collected before playing the game. 2. Fact cards are shuffled and placed in a stack, face down. 3. The teacher is the first caller and chooses from the stack and reads the fact from the card. For easy play—Read both the header and the fact. For harder play—Read only the fact and players use their skills to locate the matching square on their card. After each card, the caller lines up the card to verify the winner at the end. 4. Players check their cards after each call to see if the correct name appears on their board. If it does, the square is covered with a chip. 5. Play continues until a player gets five squares in a row. -

A Palynological Study of Two Upland Bogs in the Gulf Coastal Plain, Alabama and Mississippi Linda C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 12-11-1997 A Palynological Study of Two Upland Bogs in the Gulf Coastal Plain, Alabama and Mississippi Linda C. Pace Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Earth Sciences Commons A PALYNOLOGICAL STUDY OF TWO UPLAND BOGS IN THE GULF COASTAL PLAIN, ALABAMA AND MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Natural Sciences in The Interdepartmental Program in Natural Sciences by Linda C. Pace B.S., Louisiana State University, May 1992 May 1998 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my major professor Dr. Kam-biu Liu for his advice, support, kindness, encouragement, and understanding during the writing of this thesis, especially during the final months. I would also like to thank Dr. Liu for supplying the Minamac Bog core, the funding for the C-14 dating, and the processing lab and supplies. -

Physical and Natural Environment of the Region

Chapter 2 Physical and Natural Environment of the Region Zhu H. Ning, Project Director, Gulf Coast Regional Climate Change Impact Assessment, Southern University, Baton Rouge, LA 70813 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Physiogeographic Descriptions of Five Gulf Coastal States 2.3 Land use 2.4 Water Resources 2.5 Soil 2.6 Coastline 2.7 Current Stresses 2.8 Potential Futures 2.1 Introduction The specific territory covered by the regional assess- ment encompasses the Gulf Coastal Plains and coastal waters of southern Texas, southern Louisiana, southern Mississippi, southern Alabama, and western Florida (Fig. 1). Wetlands are a typical landscape in the Gulf Coast area. Wetlands include areas where the water table is usually at or near the surface or where the land is covered by shallow water. These habitat types are abundant in the Gulf of Mexico. Wetlands may be forested, such as swamps and man- groves, or nonforested, such as marshes, mudflats, and natural ponds. Large areas of nonforested wet- lands are found in coastal Texas, Louisiana, and Figure 1. The Gulf Coast region defined by the National Florida. Recent state estimates of coastal wetlands Climate Change Assessment. acreage (both forested and unforested) are: Alabama (121,603 acres); Florida (2,254, acres); Louisiana Alabama (3,910,664 acres); Mississippi (64,805 acres); and Most of southern Alabama lies less than 500 feet Texas (412,516 acres) (Ringold and Clark, 1980). (150 meters) above sea level. The surface of the state rises gradually toward the northeast. Alabama has six 2.2 Physiogeographic Descriptions of main land regions: (1) the East Gulf Coastal plain, (2) the black belt, (3) the piedmont, (4) the Appalachian the Gulf Coastal States Ridge and Valley Region, (5) the Cumberland The physiogeographic descriptions of five Gulf Plateau, and (6) the Interior Low Plateau (Fig.