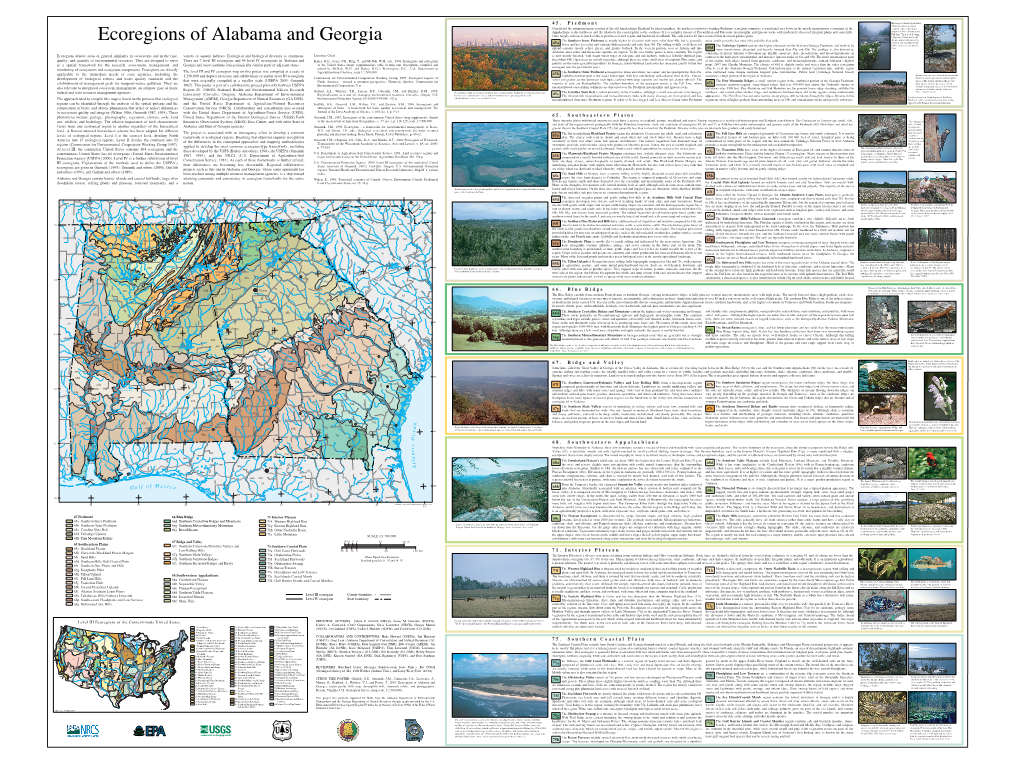

Ecoregions of Alabama and Georgia Lower and Has Less Relief and Contains Different Rocks and Soils Than 45D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama

Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 524-C Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama By JOHN T. HACK SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 524-C Theories of landscape origin are compared using as an example an area of gently dipping rocks that differ in their resistance to erosion UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract___________________________________________ C1 Cumberland Plateau and Highland Rim as a system in Introduction_______________________________________ 1 equilibrium______________________________________ C7 General description of area___________________________ 1 Valleys and coves of the Cumberland Escarpment___ 7 Cumberland Plateau and Highland Rim as dissected and Surficial deposits of the Highland Rim____________ 10 deformed peneplains _____________________ ,... _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 4 Elk River profile_______________________________ 12 Objections to the peneplain theory____________________ 5 Paint Rock Creek profile________________________ 14 Eastern Highland Rim Plateau as a modern peneplain__ 6 Conclusions________________________________________ 14 Equilibrium concept -

When the Mountain Became the Escarpment.FH11

Looking back... with Alun Hughes WHEN THE MOUNTAIN BECAME THE ESCARPMENT The Niagara Escarpment hasnt always been But Coronelli was not the first to put Niagara known by that name. Early in the 19th century it on the map. That distinction belongs to Father Louis was often referred to as the Mountain, and of course Hennepin, the Recollect priest who was the first it is still called that in Hamilton and Grimsby today. European to describe Niagara Falls from personal We in eastern Niagara have largely forgotten the observation. In his Description de la Louisiane, name, though it survives in the City of Thorolds published in 1683, five years after his visit, he speaks motto Where the Ships Climb the Mountain. of le grand Sault de Niagara, and labels it thus on the accompanying map. This is the form that So when did the name Niagara Escarpment first prevails thereafter, and it is the spelling used for Fort come into use? And what about the areas other de Niagara, established by the French at the mouth Niagara names, like Niagara Falls, Niagara River of the river in 1726. The English followed suit, and Niagara Peninsula? When did these first appear? though on many early maps (e.g. Moll 1715, I dont pretend to have definitive answers there Mitchell 1782) they use the name Great Fall of are too many sources I have not seen but I can Niagara rather than Niagara Falls. suggest some preliminary conclusions. In his Description Hennepin also refers to la The name Niagara is definitely of native origin, belle Riviere de Niagara, so the name Niagara though there is no agreement about its meaning. -

Strategy Habitat: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands

Habitat: Conservation Summaries for Strategy Habitats Strategy Habitat: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands Ecoregions: Conservation Overview: Ponderosa Pine Woodlands are a Strategy Habitat in the Blue Moun- Ponderosa pine habitats historically covered a large portion of the tains, East Cascades, and Klamath Mountains ecoregions. Blue Mountains ecoregion, as well as parts of the East Cascades and Klamath Mountains. Ponderosa pine is still widely distributed in eastern Characteristics: and southern Oregon. However, the structure and species composition The structure and composition of ponderosa pine woodlands varies of woodlands have changed dramatically. Historically, ponderosa pine across the state, depending on local climate, soil type and moisture, habitats had frequent low-intensity ground fires that maintained an elevation, aspect and fire history. In Blue Mountains, East Cascades open understory. Due to past selective logging and fire suppression, and Klamath Mountains ecoregions, ponderosa pine woodlands have dense patches of smaller conifers have grown in the understory of pon- open canopies, generally covering 10-40 percent of the sky. Their derosa pine forests. Depending on the area, these conifers may include understories are variable combinations of shrubs, herbaceous plants, shade-tolerant Douglas-fir, grand fir and white fir, or young ponderosa and grasses. Ponderosa woodlands are dominated by ponderosa pine, pine and lodgepole pine. These dense stands are vulnerable to drought but may also have lodgepole, western juniper, aspen, western larch, stress, insect outbreaks, and disease. The tree layers act as ladder fuels, grand fir, Douglas-fir, incense cedar, sugar pine, or white fir, depend- increasing the chances that a ground fire will become a forest-destroy- ing on ecoregion and site conditions. -

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

Geologic Mapping from Aerial Photography in the Boston Mountains, Northwestern Arkansas Mikel R

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 31 Article 31 1977 Geologic Mapping from Aerial Photography in the Boston Mountains, Northwestern Arkansas Mikel R. Shinn Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Geomorphology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Recommended Citation Shinn, Mikel R. (1977) "Geologic Mapping from Aerial Photography in the Boston Mountains, Northwestern Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 31 , Article 31. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol31/iss1/31 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 31 [1977], Art. 31 Geologic Mapping from AerialPhotography in The Boston Mountains, Northwest Arkansas MIKELR.SHINN Department of Geology, University ofArkansas Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701 ABSTRACT Aerial photography has been employed to map stratigraphic and structural features in the Boston Mountains of Washington and Crawford Counties, Arkansas. Exposures of resis- tant stratigraphic units within the lower Atoka Formation were delineated on a series of large scale aerial photographs over an area of about 150 square miles. -

Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas in New York

R L NS Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas in New York State Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin MLRA Explorer Custom Report L - Lake State Fruit, Truck Crop, and Dairy Region 101 - Ontario-Erie Plain and Finger Lakes Region M - Central Feed Grains and Livestock Region 111E - Indiana and Ohio Till Plain, Eastern Part 111B - Indiana and Ohio Till Plain, Northeastern Part R - Northeastern Forage and Forest Region 144B - New England and Eastern New York Upland, Northern Part 144A - New England and Eastern New York Upland, Southern Part 143 - Northeastern Mountains 142 - St. Lawrence-Champlain Plain 141 - Tughill Plateau 140 - Glaciated Allegheny Plateau and Catskill Mountains 139 - Lake Erie Glaciated Plateau Major Land Resource Regions Custom Report Page 1 Data Source: USDA Agriculture Handbook 296 (2006) 03/26/08 http://soils.usda.gov/MLRAExplorer L - Lake State Fruit, Truck Crop, and Dairy Region Figure L-1: Location of Land Resource Region L LRR Overview This region (shown in fig. L-1) is in Michigan (59 percent), New York (22 percent), Ohio (10 percent), Indiana (8 percent), and Illinois (1 percent). A very small part is in Pennsylvania. The region makes up 45,715 square miles (118,460 square kilometers). Typically, the land surface is a nearly level to gently sloping glaciated plain (fig. L-2). The average annual precipitation is typically 30 to 41 inches (760 to 1,040 millimeters), but it is 61 inches (1,550 millimeters) in the part of the region east of Lake Erie. -

Chapter 40. Appalachian Planation Surfaces

Chapter 40 Appalachian Planation Surfaces The Appalachian region not only includes the mountains, but also the surrounding provinces. During the erosion episode (see Chapter 8 and Appendix 4), rocks of the Appalachians were sometimes planed into a flat or nearly flat planation surface, especially on the provinces east and west of the Blue Ridge Mountains (Figure 40.1). But planation surfaces are also found in the Appalachian Mountains, mainly on the mountaintops. Figure 40.1. Map of the Appalachian provinces and the two provinces to the west (from Aadland et al., 1992). Due to their rolling and dissected morphology, the Appalachian provinces are rarely called planation surfaces, but they would mostly be erosion surfaces. I will continue to use the more descriptive term, planation surface, with the understanding that many of these are erosion surfaces. The Appalachian provinces exhibit three possible planation surfaces, from east to west, they include: (1) the Piedmont Province, (2) the accordant mountaintops of the Valley and Ridge Province (part of the Appalachian Mountains), and (3) the Appalachian Plateau which is divided into the Allegheny Plateau in the north and the Cumberland Plateau in the south. I also will include the Interior Low Plateaus Province to the west of the Appalachian Plateau. Many articles have been published about the Appalachian planation surface. Their origin is controversial among secular geologists, but they can readily be explained by the runoff of the global Genesis Flood. Figure 40.2. Lake on the Piedmont near Parkersville, South Carolina, showing general flatness of the terrain. The Piedmont Planation Surface The Piedmont Province begins just east of the Blue Ridge Mountains from the Hudson River in the north to Alabama in the south. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 Lrrs N and S

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 LRRs N and S Brad D. Lee and John M. Kabrick 12.1 Introduction snowfall occurs annually in the Ozark Highlands, the Springfield Plateau, and the St. Francois Knobs and Basins The central, unglaciated US east of the Great Plains to the MLRAs. In the southern half of the region, snowfall is Atlantic coast corresponds to the area covered by LRR N uncommon. (East and Central Farming and Forest Region) and S (Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region). These regions roughly correspond to the Interior Highlands, Interior Plains, 12.2.2 Physiography Appalachian Highlands, and the Northern Coastal Plains. The topography of this region ranges from broad, gently rolling plains to steep mountains. In the northern portion of 12.2 The Interior Highlands this region, much of the Springfield Plateau and the Ozark Highlands is a dissected plateau that includes gently rolling The Interior Highlands occur within the western portion of plains to steeply sloping hills with narrow valleys. Karst LRR N and includes seven MLRAs including the Ozark topography is common and the region has numerous sink- Highlands (116A), the Springfield Plateau (116B), the St. holes, caves, dry stream valleys, and springs. The region also Francois Knobs and Basins (116C), the Boston Mountains includes many scenic spring-fed rivers and streams con- (117), Arkansas Valley and Ridges (118A and 118B), and taining clear, cold water (Fig. 12.2). The elevation ranges the Ouachita Mountains (119). This region comprises from 90 m in the southeastern side of the region and rises to 176,000 km2 in southern Missouri, northern and western over 520 m on the Springfield Plateau in the western portion Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

The Logan Plateau, a Young Physiographic Region in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee

The Logan Plateau, a Young Physiographic Region in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1620 . II • r ,j • • ~1 =1 i1 .. ·~ II .I '1 .ill ~ I ... ... II 'II .fi :. I !~ ...1 . ~ !,~ .,~ 'I ~ J ·-=· ..I ·~ tJ 1;1 .. II "'"l ,,'\. d • .... ·~ I 3: ... • J ·~ •• I -' -\1 - I =,. The Logan Plateau, a Young Physiographic Region in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee By WILLIAM F. OUTERBRIDGE A highly dissected plateau with narrow valleys, steep slopes, narrow crested ridges, and landslides developed on flat-lying Pennsylvanian shales and subgraywacke sandstone during the past 1.5 million years U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1620 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1987 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Outerbridge, William F. The Logan Plateau, a young physiographic region in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 1620) Bibliography: p. 18. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.3:1620 1. Geomorphology-Logan Plateau. I. Title. II. Series. QE75.B9 no. 1620 557.3 s [551.4'34'0975] 84-600132 [GB566.L6] CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Methods of study 3 Geomorphology 4 Stratigraphy 9 Structure 11 Surficial deposits 11 Distribution of residuum 11 Depth of weathering 11 Soils 11 Landslides 11 Derivative maps of the Logan Plateau and surrounding area 12 History of drainage development since late Tertiary time 13 Summary and conclusions 17 References cited 18 PLATES [Plates are in pocket] 1. -

Immigrant Detention in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

WEBINAR Immigrant Detention in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, and the COVID-19 Pandemic May 6, 2020 2:30pm – 4pm EDT 1:30pm – 3pm CDT Featured Speakers DONALD KERWIN Executive Director Center for Migration Studies HIROKO KUSUDA Clinic Professor and Director of the Immigration Law Section Loyola University New Orleans College of Law AMELIA S. MCGOWAN Immigration Campaign Director Mississippi Center for Justice Adjunct Professor Mississippi College School of Law Immigration Clinic MARK DOW Author of American Gulag: Inside US Immigration Prisons US Immigrant Detention System ● Genesis of Webinar: A Whole of Community Response to Challenges Facing Immigrants, their Families, and Communities in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama ● The US Immigrant Detention System: Size, Growth, “Civil” Detention Population, Privatization, and Diversity of Institutional Actors ● Immigrant detainees v. persons serving time. ● Louisiana has always been one of the states with the most immigrant detainees. ICE Detention Facility Locator: https://www.ice.gov/detention-facilities COVID-19 and US Immigrant Detention System ● “Confirmed” COVID-19 Cases: (1) March 27 (no “confirmed” cases among detainees), (2) April 20 (124 confirmed cases), (3) May 4 (606 confirmed cases in 37 facilities, and 39 cases among ICE detention staff). Source: https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus ● These figures do not count: (1) former detainees who have been deported, (2) ICE contractors (private, state and local, and others); and (3) non-ICE prisoners/detainees held with ICE detainees. ● ICE detention population: March 21 (38,058), April 25 (29,675). ● Social distancing is “nearly impossible in immigration detention.” As a result, ICE should “implement community-based alternatives to detention to alleviate the mass overcrowding in detention facilities.” Open letter to ICE Acting Director Matthew T. -

Monte Sano Civic Association Newsletter

Monte Sano Civic Association Newsletter June · July · August 2019 Civic Association Potlucks MSUMC Recycles Cans for MADD So many of you came to the last potluck in Monte Sano United Methodist Church April, and we’re hoping to see as collects aluminum cans for recycling, many or more of you at the next proceeds of which are used within Alabama gathering on Tuesday, August 20th to promote the mission of MADD: “To aid at 6pm at the Monte Sano Lodge. the victims of crimes performed by Just as last time, paper products will individuals driving under the influence of be provided. Please bring a dish to share. If alcohol or drugs, to aid the families of such you wish, bring a bottle of wine to share as victims, and to increase public awareness of well! Babysitters will be on hand for the problem of drinking and drugged activities for the kids, so families of all ages driving.” This project is in memory and and sizes are welcome! Kem Robertson will honor of Chris Hall, a mountain resident be speaking about the new Monte Sano whose injury by a drunk driver resulted in State Park Association, a Friends group that quadriplegia. The bin for cans in located in will support the park. (See page 2.) the parking lot at the back of the church. Mark your calendar for the final potluck of the year: Tuesday, December 10th, also at Welcome to our NEW Monte Sano Lodge. More details to come. and RETURNING members! Kids In the Creek At the April potluck, we had 24 households either join or reinstate their Kids of all ages can hunt for aquatic critters MSCA membership.